|

|

Behind the Story

This is the final piece of “School’s not out,” a series of stories from the road this summer about child care providers and the communities that rely on them in every season. Go here for past stories in the series.

As most K-12 schools and community colleges took their summer breaks, and the budget-making process stretched over the summer months, most early childhood programs kept going.

Summertime — and this summer in particular — represents two truths about the state’s early care and education programs: They are especially fragile. They are especially needed.

Eager to see how providers and communities were navigating these truths, I decided to hit the road.

In all 100 counties, including the seven I visited in July and August, programs are facing a financial cliff that will lead to closures without help from the government. A Century Foundation report projects 1,778 of North Carolina’s programs will close as federal relief funds run out, and 155,539 children and families will lose access.

Advocates and legislators in the early childhood caucus have requested $300 million to avoid the cliff in this year’s budget, but the money has not shown up in the House and Senate proposals. The final budget negotiations are still under way. The grants run out at the end of this year.

Many programs, including the 15 facilities I visited, do not see a path forward for child care without a change in its financial structure. Several said they do not see a path forward in the next year.

And yet communities need these programs — and they need many more of them. In Wilkes County, which completed a study this summer to try to put a number on that need, they determined they need 836 additional child care slots (almost double what they have).

Summertime adds another layer of community need. K-12 summer closures mean families are crunched for care for school-age children as well. Programs shift to accommodate those needs, operating summer camps and often caring all day for the children they usually serve before and after school.

Owners and directors at all 15 facilities I visited operate waitlists. They field calls from desperate parents weekly. They do not know how to help.

“There’s just nowhere for them to go,” said Emily Leonhardt, assistant director of Calling Kids Development Center in Hiddenite. “There are other child care facilities, but they don’t have open spots.”

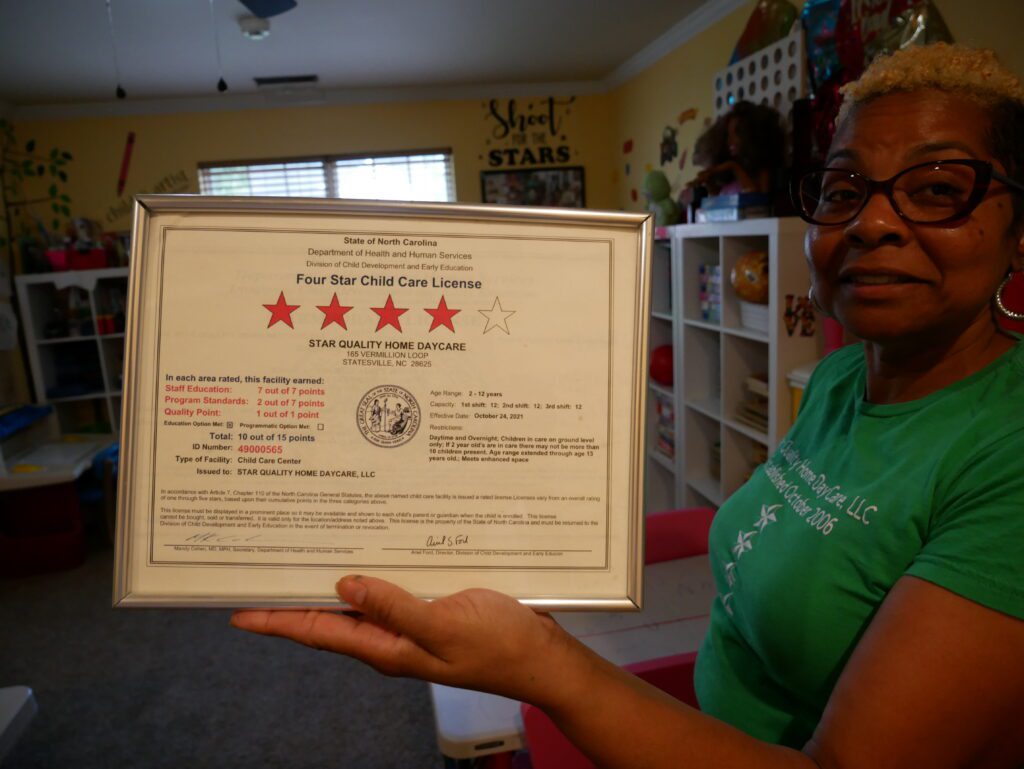

I visited a handful of counties (Wilkes, Ashe, Alexander, Iredell, Warren, Robeson, and Pitt), spending as much as time as possible in programs serving young children. I visited 15 child care facilities (centers, homes, church-backed programs, nonprofits, for-profits, Early Head Start programs, programs that serve children with special needs, a program attached to an adult day home, a program whose roof caved in, a program that was flooded, a program that just opened, several programs that might close soon, programs rated five stars, one star, and everything in between). It’s worth noting that there are other early childhood programs that do indeed close in the summer: programs attached to public schools and Head Start programs. Because these programs have consistent public funding streams, they did not receive the stabilization funds that are running out.

I spoke with 102 educators, administrators, parents, Smart Start personnel, business leaders, other local advocates, and one reporter from The Taylorsville Times. I asked them about the importance of child care in their lives. I asked them about how the looming financial cliff is affecting their day-to-day operations and their communities as a whole.

I played a lot.

I wrote along the way — about Wilkes County’s locally driven solutions, Ashe County’s vision through a partnership between early childhood leaders and the school district, Alexander County’s dwindling access and its remaining providers’ grit and passion, a regional nonprofit child care chain opening a new Pitt County location and convening cross-sector leaders to push for change, and the unique role family child care homes play in communities like Iredell, Warren, and Robeson counties.

Here’s what else I learned.

Higher prices, less space soon

Parents soon will have an even harder time finding and paying for child care. The quality of that care, in terms of class sizes and staff experience, probably will be lower.

That’s what a survey in April of 2,518 child care providers found.

And that’s what the providers echoed during my visits. They told me they will have to increase tuition rates and staff-to-child ratios, and will struggle to recruit the right folks for the job.

No decision feels right in the current financial model, providers said.

“We don’t want to stretch our families so that we lose our enrollment numbers if we do increase prices, but we don’t want to underpay our staff and potentially have them wanting to find other means of employment,” said Jade Deese-Jones, director of Tiny Steps Learning Center in Lumberton.

Pockets of momentum

There are initiatives across the state aimed at expanding communities’ awareness of child care’s challenges and advocating for increased funding, business supports for owners, teacher pipeline-building efforts, and increased access to quality care.

In many communities I visited, leaders had recently signed on with Building Bright Futures, an apprenticeship effort out of the North Carolina Business Committee for Education. In Ashe County, for example, all centers were signed up to send teachers back to school while they worked. Building Bright Futures is connecting early childhood programs to ApprenticeNC and providing funds for tuition and wages for providers.

That’s how Rebecca Rash, director of Ashe Developmental Day School, said she was going to sustain the increased wages she established through stabilization funds as they run out.

There is also a new family child care project from Southwest Child Development Commission, funded by the state Division for Child Development and Early Education, which is aimed at addressing many of the problems family child care providers shared with me.

In many places, local cross-sector relationships are forming.

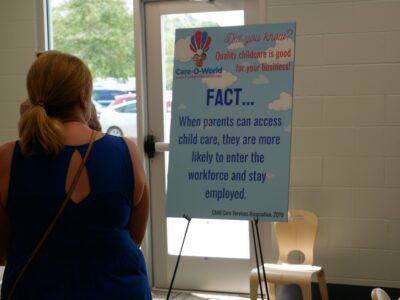

At the open house I attended for the new Care-O-World Early Learning Center in Ayden, for example, the providers are on a mission to act as a community convener. They extended invitations to tour their new facility and learn about the field’s challenges to business owners, local and statewide politicians, early childhood faculty at Pitt Community College, their chamber of commerce, and other local leaders. And people showed up, intrigued and eager to learn. Many had not set foot in a child care center in decades, if ever. But many attendees told me they knew something needed to change because of labor shortages across industries.

Cindy Goff, a commissioner for the town of Ayden, told me she’s been hearing from frustrated employers unable to hire people. Child care is needed for families to work — and for communities to continue existing, she said.

“It’s economic development and it’s residential development,” Goff said. “And then it’s also about keeping your educated young people in the community to continue to enhance the community. It’s all cyclical.”

The business community was at the center of efforts in Wilkes and Ashe counties. The Wilkes Economic Development Corporation hosted a child care task force pushing for solutions. Kitty Honeycutt, director of the Ashe County Chamber of Commerce, is one of the leaders behind the child care model for which the county is requesting legislative funds.

Philanthropic organizations are also playing a role in local efforts. Dogwood Health Trust is funding early childhood workforce initiatives in the western region. The Leonard G. Herring Family Foundation funded the study in Wilkes County.

Those efforts can only go so far, said Johanna Anderson, a consultant working with the foundation in Wilkes.

“Child care is not a privately funded solution solely,” Anderson said. “We can spark ideas, we can do some research, we can do some seed funding. But to really move the needle on child care, it’s going to have to include public resources, both existing and new.”

Relationships matter

These cross-sector relationships are further along in some communities than others. I heard of tense relationships between school districts and Smart Start partnerships. I heard of some chambers of commerce that were simply focused on other issues.

In Alexander County, Smart Start executive director Paula Cline told me the lack of institutions housed within the county was a barrier to forming alliances she sees in other places.

“We don’t have a chamber of commerce here,” Cline said. “We don’t have a hospital. We don’t have pediatricians in this county. We have such high needs and … a lot of our services come from adjoining larger counties.”

In Robeson County, Christopher Locklear, a realtor and board member of the Robeson County Partnership for Children, said his eyes have been opened in the last couple of years to the problems families and child care providers face. He’s connected to local chambers of commerce and has spoken with legislators to advocate for support. But he said he feels there is still a lack of understanding within the older generation that often holds positions of power.

“Sometimes it may not come up because of the demographics of that board,” Locklear said. “If they’re older, they may have grandchildren or great grandchildren, but that doesn’t impact your life as much as having young kids. I’m wondering, how many of our state legislators have children at a young age right now?”

Staffing is everyone’s biggest challenge

Cline, from Alexander County’s Smart Start partnership, started in child care with her own home-based program. Now she advocates for the field she had to leave.

“The circumstances can force you, no matter how much passion you have for it, to have to go somewhere where you don’t want to go, but you have to because of your family’s circumstances.”

Cline is worried that more and more teachers will make that decision as some owners and directors will be unable to pay competitive wages as stabilization funds end. Providers across communities said the same.

Towana Neal, owner and director of WanaPooh Daycare in Orrum, said she does not know how she will survive when the funds stop. She’s using the funds to pay her one other teacher.

The other most common challenge that providers described was mental, social, and emotional challenges of children, families, and teachers.

The stress and isolation of the pandemic are still very much rippling through classrooms. Kimberly Long, assistant director at New Beginnings Child Enrichment Center in Stony Point, said she’s seen a spike in the number of children per classroom experiencing developmental delays.

That makes staffing even harder, Long said.

“(In) every classroom, at least half the kids have a developmental delay that we’re having to work with, understand, move forward with — with the whole classroom and then with that child independently,” she said. “Then these people come in, and they want to work here. And then they see this and they’re like, ‘This is too much for me. How do y’all do that?’ They’ll leave on their lunch break and not come back.”

These truths of this summer — the fragility and necessity of early childhood programs — reminded me of the pandemic, when programs were also fragile — taking on health risks and additional costs — and needed — deemed “essential” for front-line workers’ children and taking in children who needed a safe place during K-12 closures and remote learning.

Eager to move on from the pandemic, we forget the extent to which people who kept our communities running are still recovering.

“We did feel a sense of relief whenever the grants started, because we felt like, ‘OK, finally, we’re going to get the help that we need, and our employees aren’t going to feel like they’re underappreciated,'” said Deese-Jones, the center director in Lumberton.

When asked what she would hope people in power understand about her facility’s challenges, Deese-Jones said:

“I do hope that they see what a tremendous help this has been for child care facilities, and I hope that no more of our facilities have to close, because the need is there,” she said. “The demand is there. We just can’t keep up with it.”

A huge thanks to every single person who welcomed me into classrooms and communities. Sign up for Early Bird below, EdNC’s early childhood newsletter, to follow EdNC’s coverage through the fall, as the state budget is released, the cliff comes closer, and we look to other states for examples of early childhood policy leadership.

Sign up for Early Bird, our newsletter on all things early childhood.

Recommended reading