This story originally appeared in North Carolina Health News and is shared by EdNC through a content-sharing agreement with nonprofit news organizations in North Carolina.

Amy Widderich is a woman in near constant motion.

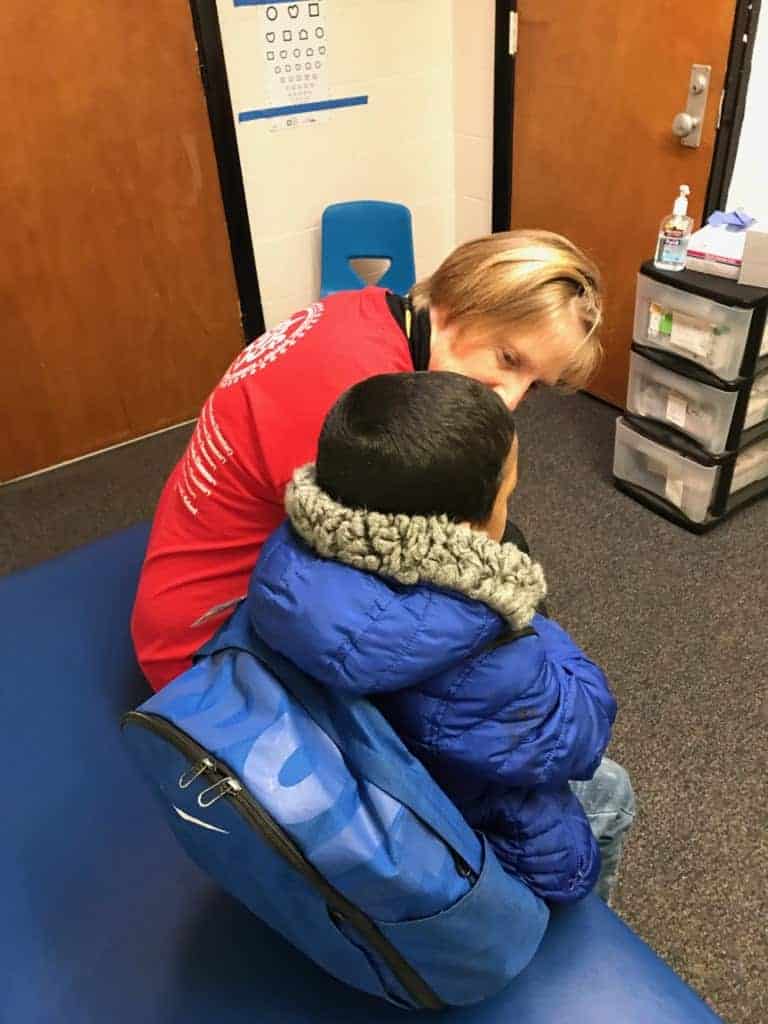

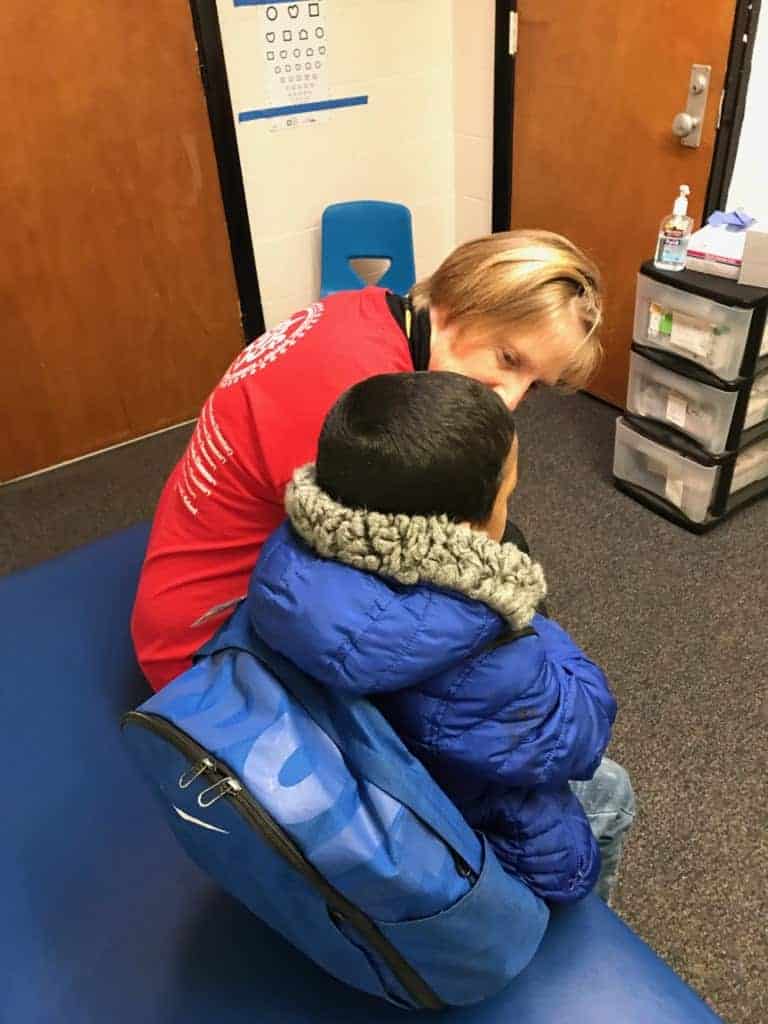

Whether it’s walking a queasy child from a classroom, taking a temperature or dispensing hugs and encouragement to anxious kids, Widderich, the school nurse at Grove Park Elementary School in Burlington, rarely gets to complete a sentence before she’s interrupted by a child, or a teacher, or one of the other staff at the school.

“I get here early so I can catch up on email, check for faxes, get myself organized, and in the morning I usually greet the kids,” she said when asked how her day looks. “I have a couple of students who come in and take daily meds, and then the flow of kids off of the bus starts.”

Sure enough, once kids start swarming into the building, a handful of them make their way into the health room next to the principal’s office. By 7:40 a.m. there’s one child with autism sitting on the daybed eating breakfast, another arrives complaining of a tummy ache, all the while a teacher bends Widderich’s ear about a student whose psychiatric medicine seems to be making him more agitated.

Just a typical day

Widderich takes it all in stride. What she’s able to do – dig in, get to know students and staff, teach prevention activities, monitor illnesses, administer medications and more – has been made possible, in part, because Grove Park is the only school she’s responsible for.

But across North Carolina, most local school districts are unable to have a nurse in every school. About 41 percent of school nurses serve one school, 36 percent serve two and 22 percent of school nurses serve three or more schools.

At the request of lawmakers, the legislative Program Evaluation Division last month presented a report concluding that in order to meet the state’s own staffing goal for nurses, the legislature would have to spend about $45 million annually. If the state wanted to have a nurse in every school, that price tag could shoot up to about $79 million per year.

21st century nurse

There is a prevailing image of the school nurse: someone who has a quiet office down the hall, who dispenses aspirins and puts cold compresses on foreheads.

That makes Widderich, and every other nurse interviewed for this story, laugh.

About one in 10 children in North Carolina is born premature, and a similar percentage have low birth weights (many are likely the same children, but not all). That brings with it a legacy of health problems, especially earlier in life.

And in Alamance-Burlington schools’ annual survey, the district’s nurses reported an average of 63 students per elementary school were taking a medication at school (the district’s 20 elementary schools averaged 527 students each).

“In today’s world, students have complex needs,” said Donna Mazyck, head of the National Association of School Nurses. She noted that in the past, kids with health problems might not make it to school, or they might end up in a “special” school. Now kids with issues – from autism, to hearing loss, to diabetes, to more serious diseases, like cancer – are mainstreamed into public schools. That has happened because of state and federal laws, and because parents have demanded it.

Exhibit one for Widderich is the cabinet where she keeps asthma inhalers, hung above the drawers with all of the oral medications. Because Widderich is at the school full time, she has been able to do train the children in how to use their inhalers more effectively. She is also able to monitor whether their inhalers are working, as she did earlier in the school year with one boy.

“He really was wheezing, he would make it about four hours, and he would come in and he would be wheezing. I spent a lot of time making sure that he could use the inhaler correctly and using proper technique and measuring his oxygen saturation,” she said. “One day we were here and I had to call mom and say, ‘You know what? He really is just not improving with his inhaler and you need to make a follow-up appointment.’”

The child ended up with a steroid inhaler, which gave him longer-term control of his disease, rather than relying on a “rescue” inhaler.

Widderich has trained teachers and staff to monitor kids as they take their inhalers, but her nursing skills help her examine inhaler use more astutely.

“[The] inhaler is with the teacher, and the kid is using it before they go outside at recess, is it working? Is it helping…like before they used it, did they need it? How often?” she said. “You know we just have inhalers willy-nilly, but what’s the outcome?”

Health linked to poverty rate

Grove Park is a Title I school, a federal designation which notes that at least 80 percent of the children in attendance qualify for free or reduced meals. All of the 500 or so kids at Grove Park come from families with incomes at or below the poverty line, about $32,000 per year for a family of four.

The fact that all of the school’s children qualify says something about the poverty present there. And kids in these schools have higher needs, said Donna Daughtry, a Wake County school nurse who did research on a model to determine the right number of nurses in schools.

“Part of our formula was things that were based on low income,“ said Daughtry, who noted that 30 percent of the weighting in their staffing formula was based on the number of kids qualifying for free and reduced meals.

“We looked at identified health conditions that were already at the school, and we looked at the number of invasive medical procedures that were already there, we looked at performance [scores] and then we also looked at limited English proficiency,” she said.

Other data back up this idea. For instance, recent data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention noted that children in families living below the poverty line had a higher incidence of asthma.

Beyond firefighting

Widderich once split her time between two schools.

“You have to meet the needs of your students that have chronic health conditions that require medication, and the process of delegating and making sure each one is safe and the people who were taking care of them there know how to do it safely,” she said. When she was only at a school for half her time, Widderich said a lot of it was spent “putting out fires.”

Principals, administrative staff and teachers do respond to children’s health needs, but that erodes teaching time, discipline and affects the rest of the classroom. It also reduces “seat time” for the kids with health issues, Widderich said.

“We had a couple of schools [in the district] where kids are coming to the office all the time and they were being sent home,” she said. Once a nurse was placed in those schools, “something like 95 percent of those kids being sent to the health room were returning to class.”

Her observations are backed by research, which has shown that having nurses available to students meant that children were absent less often and were less likely to be sent home if they complained of being ill. This is also important for parents who work low wage jobs, often without paid time off.

“Parents have to work, they have to be able to go to work and if they are having the school calling them all the time and because their child with diabetes has an issue, it makes it very difficult for them to maintain their employment,” she said.