When folks at D.C. Virgo Preparatory Academy, then a middle school in New Hanover County, heard about the chance they would become a laboratory school, Principal Sabrina Hill-Black started meeting with parents and community members. In the spring of 2018, Hill-Black held forums to discuss what families might want from this new school model, which was created by the legislature in 2016 to form partnerships between struggling schools and UNC-system universities.

From the beginning, Hill-Black said parents were on board with one of the biggest changes that came from the school’s switch from a traditional public school to a lab school partnered with UNC-Wilmington — its shift from a middle school to a K-8 school. Why make that change?

“Knowing we have an opportunity here to do something different, something innovative,” Hill-Black said. “There’s no K-8 school here in New Hanover County. One of the biggest, the most important ideals behind it was our new motto: where families come to school together.”

Hill-Black said she knew many families who had siblings going to three or four different schools. She gave an example of a mother who was new to town dropping one child off at high school, one at D.C. Virgo as a middle school, one at an elementary school, and one at a pre-K center around the corner.

“Why can’t three of those children come to school together?” Hill-Black said. “So now they do. We have numerous families that have two or more children in the building, and they’re doing one stop daily for their children. We’ve always been focused on family, community, and meeting the family needs, so we just felt like that was important.”

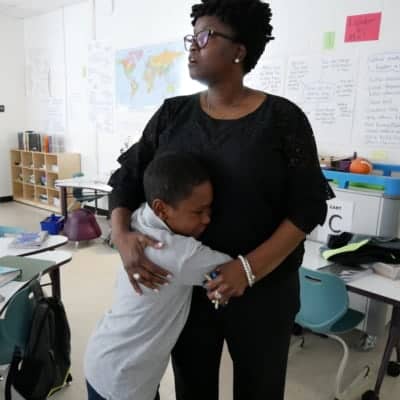

Hill-Black said the change allows the school to build deeper relationships with families. When incoming kindergarteners recently visited D.C. Virgo to be assessed on their needs, she said she referred to some of the children as “grand-students” who had multiple siblings who were already enrolled or who had previously come through the school.

“We know them already,” she said. “Their parents are comfortable sending their children to us.”

One of the motivations behind laboratory schools is to “provide enhanced educational programming to students in low-performing schools,” according to the UNC-system’s website. Hill-Black also saw the grade expansion as a way to start providing those enhanced educational opportunities to children when they were younger.

“I think about building a strong foundation for children, especially kindergarten through second, kindergarten through third — knowing our children and knowing our families to help build that stronger foundation from the very beginning of their early early elementary years will help continue that stronger foundation as we prepare them for high school,” Hill-Black said.

The school has 214 students and does not plan to expand much more — its max is 270. The existing facilities had extra room for the addition of six more grades. Bill Sterrett, interim associate dean for UNC-W’s Watson College of Education, said the university, its faculty, and their expertise can have a significantly wider reach over nine grades instead of three.

“We’re seeing opportunities whether you’re in leadership, or Pre-K, early childhood — we are wanting to invite as many faculty and staff at UNC-W to invest their talent, their expertise, their energy, and their time in this work,” Sterrett said.

The school now operates outside of New Hanover County Schools. Instead of the district, Hill-Black reports to the Watson College of Education Dean Van Dempsey. All employees are paid by the university instead of through the district.

But partnership with the district has been a key aspect of the opening and current operation of the school, both Hill-Black and Sterrett said. The local school board unanimously approved the lab school decision. The district superintendent is on the school’s advisory council. Middle school students still participate in sports through the district, and D.C. Virgo teachers and administrators are part of professional development activities with district faculty.

This partnership is beneficial for both parties, they said, for obvious reasons: “They’re here kindergarten through eighth grade,” Sterrett said. “In ninth grade, it’s understood that they are most likely going back to a New Hanover County public school. And we have a shared vested interest in student success.”

A key component of the lab school model is to provide a chance for university students studying teaching and administration to get hands-on experience.

“We are here to educate students and students who have specific learning needs, in some cases, but a major aspect of it is teacher prep and principal prep,” Hill-Black said.

That’s something you can’t miss walking around the halls of D.C. Virgo. Throughout its first year open, Hill-Black said over 60 UNC-W education students have been able to acquire field experience from working alongside teachers at D.C. Virgo. A social work intern has been working with the school’s new social worker. More than 40 UNC-W faculty have been involved in the school’s first year.

One UNC-W professor is opening and operating a new STEM lab next year. An early learning professor has arranged kindergarten entry events where incoming kindergarteners get to visit the nurse, classroom, and teachers before their first days of school. Two principal interns that were also part of NC Principal Fellows have worked at the school, gaining invaluable experience.

The first principal intern helped Hill-Black open the school, from creating a master schedule with teachers to handling logistics like transportation to observing instruction in the classroom.

“His first experience was on a Sunday, mid-morning, helping us move furniture,” Hill-Black said with a laugh.

What does this new partnership do for D.C. Virgo students?

Sterrett explained it like this: “They really have a lot of choice, voice, and agency.”

In discussions with teachers and administrators on what extra programming students might want beyond the normal academic courses, teachers decided to ask their students instead of deciding for them. Middle schoolers filled out a survey, which came back with a common response: entrepreneurship.

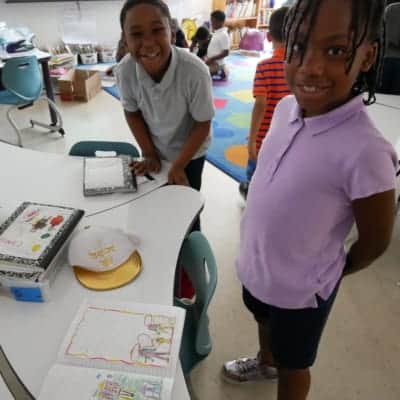

A UNC-W partner, the Brian Hamilton Foundation, came into the school to help students in grades 6-8 develop basic skills in starting a business. Elementary school students, Hill-Black said, were also encouraged to think about how to create things from basic household items. The “Hamilton Challenge” encouraged one family to start a lawn care business on the side.

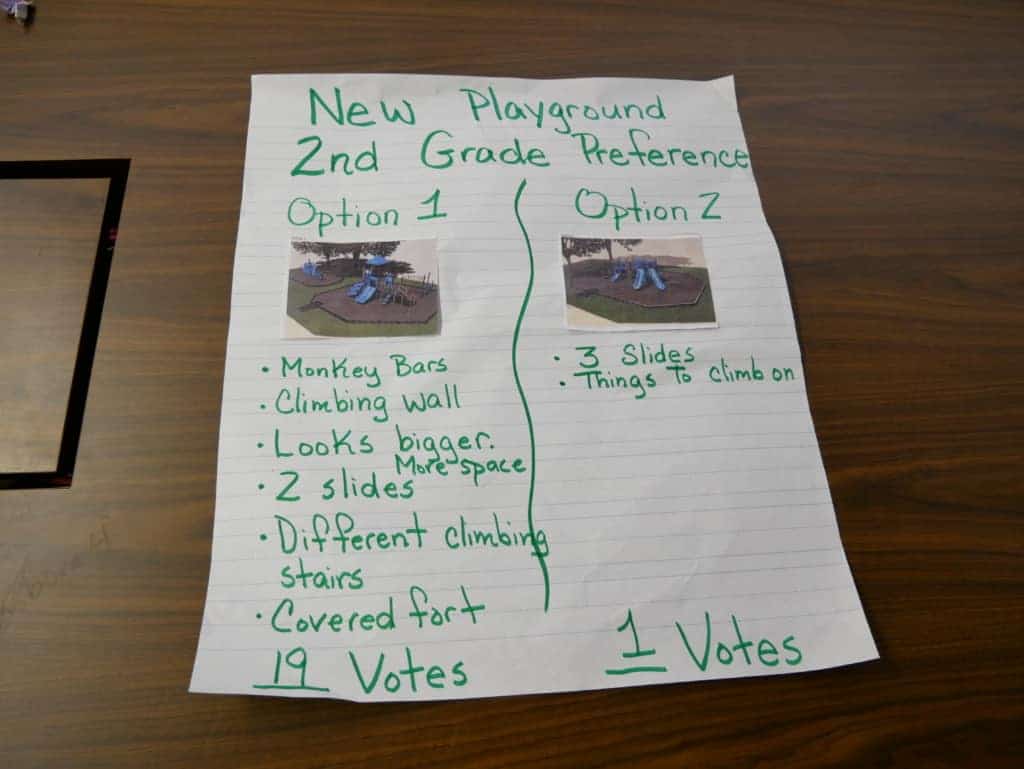

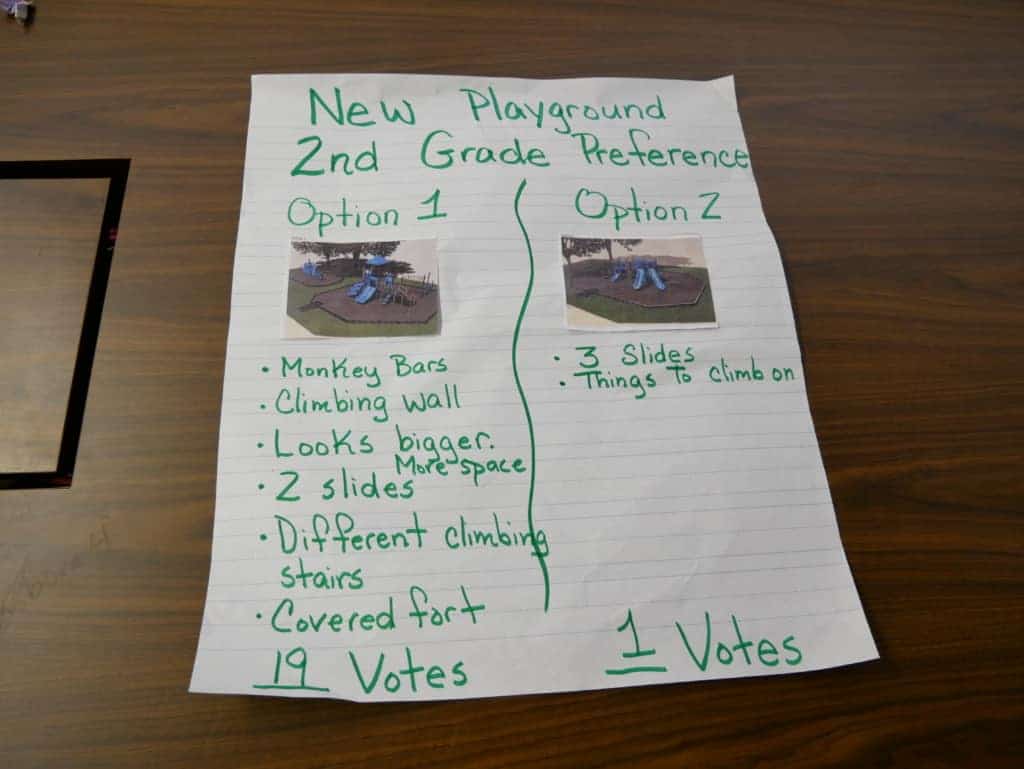

As choices are made within the school, student voice is put at the forefront. One important addition in the transition from a middle to K-8 school was a playground. All students, even kindergarteners, were asked which designs they favored and were able to weigh pros and cons on playground components. The playground design they chose will hopefully be open for the upcoming school year, Sterrett said.

Another strategic change for D.C. Virgo students has been the infusion of action-based learning across the school. A classroom for younger students is set up with activities that get students moving while learning. Upper grades have those activities embedded into their classrooms. Sterrett said adults have trouble sitting still for long periods of time, but kids have an even harder time doing so. Research shows students’ cognitive ability improves when they are physically active.

“How can we engage them so that we don’t have punitive things of taking away recess or anything, but instead we’re adding movement … into their daily schedule?” Sterrett said.

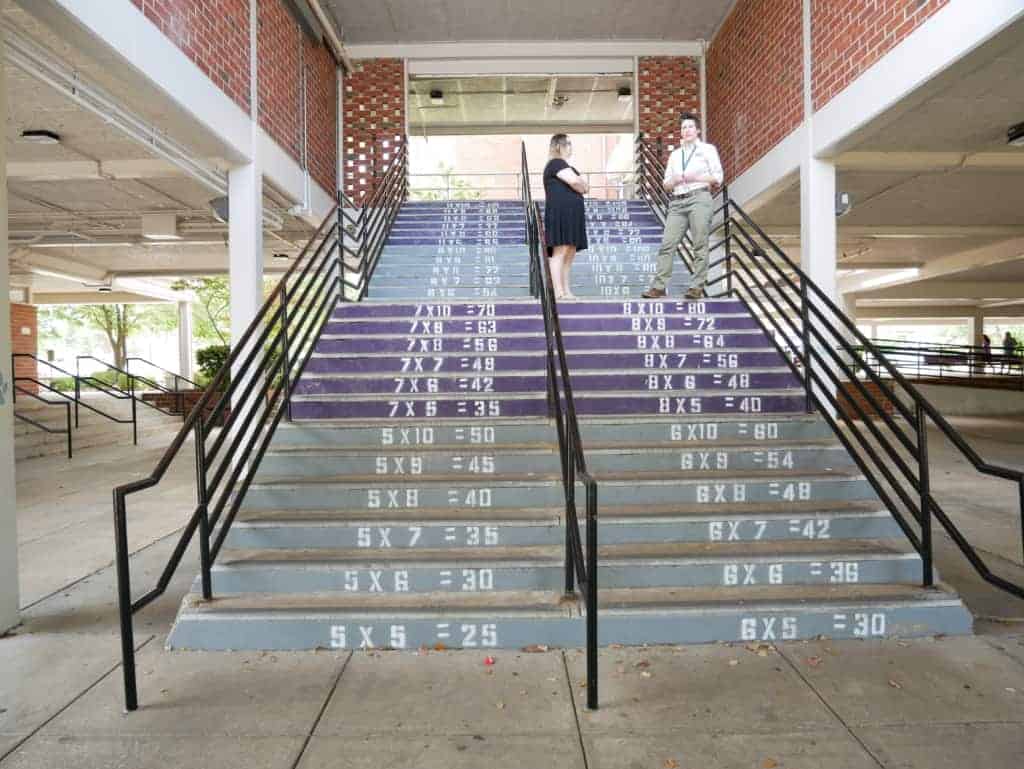

Partnership is a strategy Hill-Black takes seriously, not just in the form of the university partner. A community group called Work on Wilmington built an outdoor classroom and standing desks for students to work from. The group also painted the school stairs with multiplication tables. The pastor from one of the school’s neighboring churches volunteers daily. A Blue Ribbon Commission created a parent room, which Hill-Black still uses for parent meetings and to provide parents a place to work on job applications. The school’s second PTA-sponsored bingo night is coming up, where parents meet with teachers and are given students’ progress reports. The school nurse, provided by MedNorth, is hosting vision and dental screenings for parents next year.

As far as performance results, Hill-Black said she is still waiting on test scores from the school’s first year. She said there are social, emotional, and behavioral changes in students she can already see. One student was so afraid to walk up the multiplication table stairs that her teacher worked with her one-on-one to reach a different multiplication table each time. Other adults in the building got on board to support the student’s progress up the stairs.

“One day I said, ‘You want to go to the library with me?’ ‘Well what’s up there?’ I said, ‘You have to get up there and see, I can’t tell you.’ It took encouragement,” Hill-Black said. “Now, that child goes all the way to the top, no problem. You won’t see that in data.”

This is the third part in a series on North Carolina’s lab schools. To read an overview of lab schools, read the first article here. Read a profile of ECU Community School, a lab school in Pitt County, here.