Editor’s Note: This article is the first of a three-part EducationNC series on Greene County’s STEM (science, technology, engineering, and math) program.

When Caroline Radford started high school at Greene Central High School, she said she described herself as a shy person. She felt uncomfortable speaking in front of others. Now, after a few years in Greene county’s STEM (science, technology, engineering, and math) program, Radford is a STEM ambassador and is eager to be a leader.

“I kind of came out of my shell,” she said. “I want to be a role model for other people.”

Middle and high school ambassadors like Radford often volunteer to present about the Greene County program to other schools and generally act as experts to interested peers or anyone who wants to know more about STEM education.

It all starts with interesting opportunities. Radford loves her forensics class because it is intriguing and offers something different from traditional subjects. Timothy Speight, another ambassador at Greene Central High, bubbled with enthusiasm as he talked about a STEM project he completed with his class to build a lie detector. At first, Speight said, he didn’t think it was possible.

“As we got deeper, we learned to connect the pieces together,” Speight said. Eventually, the class created an application where someone could put two fingers on a pad that is linked with a screen that would display physical indicators for lying.

Greene Central Principal Patrick Greene said the school is seeing the results of removing the traditional curriculum restrictions and creating a place where students are genuinely interested in school activities.

“The old model of school doesn’t necessarily fit with where we’re going,” Greene said.

While touring Greene County Middle School, the ambassadors bragged about their Pitsco STEM lab instructor, Jennifer Walmsley who leads the elective course with two levels. The first focuses on math and the second is a more independent course.

Independent study is commonplace in classrooms dedicated solely to STEM and part of the curriculum with a STEM focus. Teachers offer support to student-driven learning.

There are computers throughout the lab, each with some kind of instructional model or program. Usually, students are paired up and work through the steps of the model together. If students need assistance along the way, there are small lights they can activate above each station to indicate to Walmsley that they need help.

Meredith Warren, a middle school ambassador, demonstrated how to use a small machine called a Z-Mill, which can be used manually or programmed to move in a certain pattern. Walmsley proudly showed her students’ progress — the improvement once students went from operating the machine manually to being able to program.

Walmsley talked about other projects she assigns like creating a cake box. Students have to construct a plan, have a design, and then build a three-dimensional cake box. She said that even in a small assignment like this one, students see their progress and want to perfect their creations.

“They don’t mind going back and doing it again,” Walmsley said. “They’re working to make it a better product.”

She said she builds the pace of the class and specific deadlines around students.

“I don’t mind letting them take two weeks when it should have taken two days,” Walmsley said.

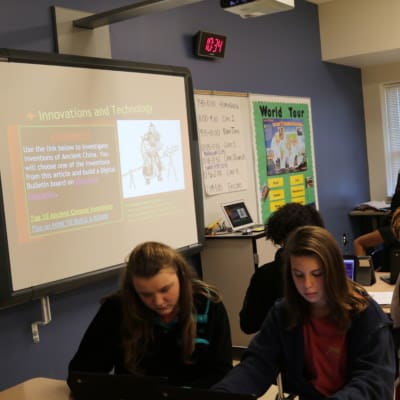

In Thomas Loftin’s sixth grade social studies class, STEM is integrated into unlikely lessons. While working on an ancient Asian culture unit, students had done their own research on Chromebooks the day before and were venturing off on studying their own interests.

Loftin explained that he was planning a future lesson that would incorporate workplace skills with social studies. Through The North Carolina Business Committee for Education’s Teachers@Work, Loftin was able to spend time in the emergency room at the Lenoir Memorial Hospital in Kinston.

He learned how doctors triage patients’ needs. Loftin is applying the experience to the classroom by incorporating the ER technique into a lesson on how surgeons in ancient battles would treat injured soldiers. The next month, he plans to take students on a trip to visit the hospital themselves to see the practice in a real-life situation.

In Matthew Gnau’s science class at Greene Central High, students started their first day of “a grand challenge.” Gnau could not give a lot of information on how the challenge would play out since he was learning right alongside his students.

Initially, all they knew was they were supposed to create a new way of storing information within the body; Gnau called it “a new form of DNA.”

After research, students created a blueprint to plan out their projects. “They’re encouraged to use our 3-D printers to come up with this molecule,” Gnau said.

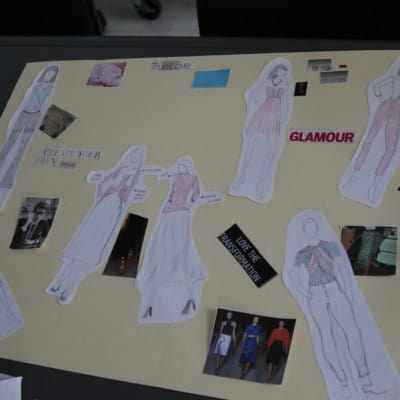

When a program is this comprehensive, STEM find its way into classrooms like Jean Brendel’s family and consumer sciences (FACS) class.

Whether teaching embroidery, sewing, organic tie-dying, or fashion design, Brendel shows students how many complex factors go into making something from scratch. She has had more than one former student tell her how her class helped them see that.

“They’re learning that apparel has all types of science in it,” Brendel said.

Brendel involves students in real-life projects as much as possible. Her students make drawstring bags and fill them with toiletries for military families around Easter. She hopes to partner with Spoon Flower in Durham so students can create their own designs with computer software and them have them made into fabrics. One of her students is designing and creating stoles for students who graduate as STEM scholars.

In Ashley Shiosaky’s art class, students used Rubik’s Cubes to create large pictures, shown in the time lapses below. Shiosaky said students had to learn how to solve at least one side of the cube to make sure the right color was facing frontwards. Then, they determined which colors they needed in each row to make the larger picture come together.

Shiosaky said she was amazed at how the projects have brought students together, teaching lessons on teamwork.

“Kids who would’ve never spoken to each other work together,” Shiosaky said. “The star of basketball team and a freshman kid who never talks became good friends.”

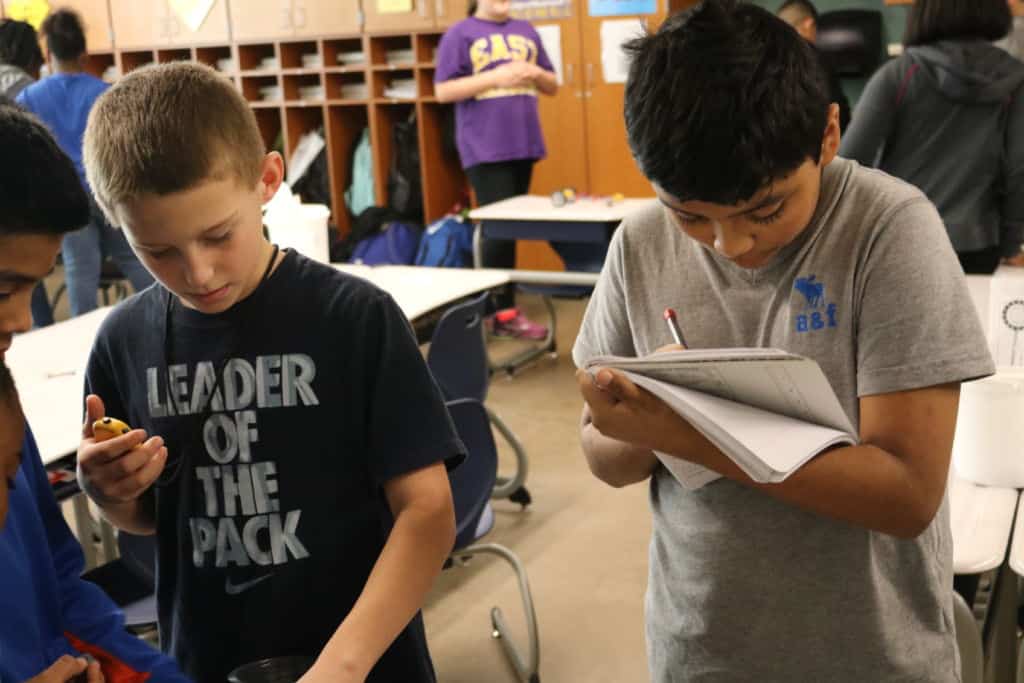

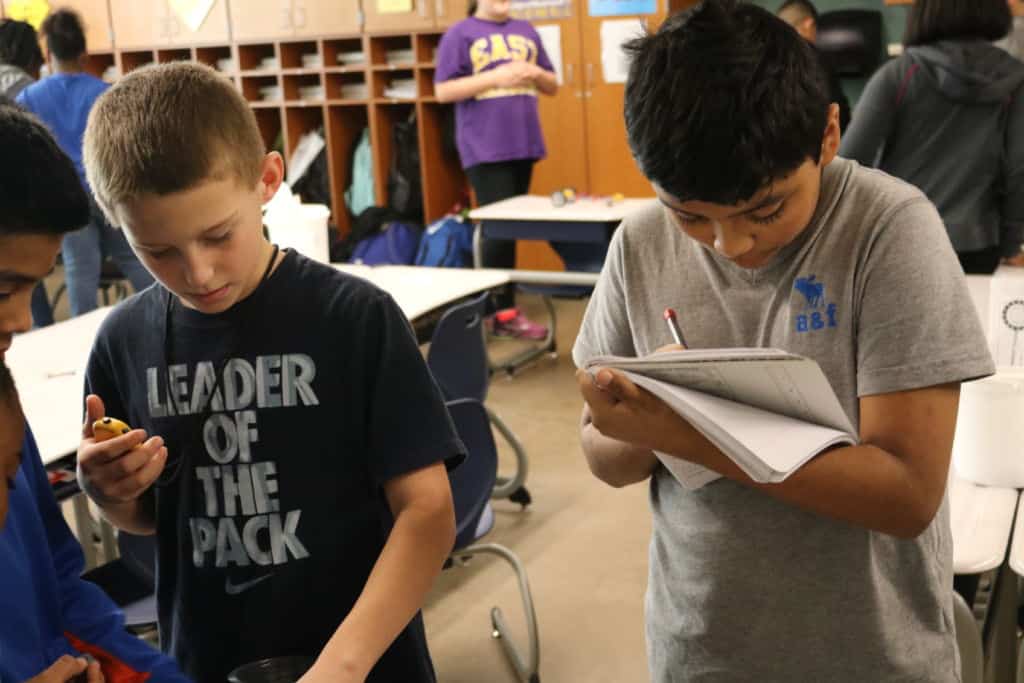

But before students reach middle or high school, they are being taught in a STEM mindset. They are working in groups, doing experiments, and being exposed to STEM in different ways. In Nadine DeLallo’s fifth-grade class at Greene County Intermediate School, students saw how far a small-wheeled machine would go with different weight added to a string. After receiving instructions, they worked on their own, with each student in the group having a different role: one with a stopwatch, one adding washers, and one recording the team’s results.

Greene County Public Schools Superintendent Patrick Miller said it is important to develop these skills early on.

“Part of intelligence is, if you don’t know what the answer is, you look elsewhere,” Miller said.