Marking the 20th anniversary of a lawsuit around equal opportunity in public schools, both sides in the Leandro case (Leandro v. State), in a joint motion Monday, called for an independent consultant to make recommendations on how to ensure quality education for every North Carolina child.

Melanie Black Dubis, the lead counsel for the plaintiff school districts in the suit, said the independent consultant is necessary to securing the constitutional rights of all children.

“For decades, hundreds of thousands of North Carolina children have left our public schools not performing at grade level and therefore not having received a sound basic education,” Dubis said in a statement. “A comprehensive, detailed plan, developed by an independent expert consultant is the first step to guaranteeing that we do not fail one more child.”

Bill Cobey, the chair of the State Board of Education, however, said he doesn’t see how an independent expert is going to help.

“I respect everybody involved in this, but I don’t know what an independent consultant is going to come up with that we haven’t come up with through the years,” Cobey said, adding that he was speaking for himself and not the entire State Board.

The State Board filed a separate motion asking to be removed from the case. The motion states that the North Carolina education system is different now and that the original complaints of the Leandro case no longer apply.

“Because the factual and legal landscapes have significantly changed, the original claims, as well as the resultant trial court findings and conclusions, are divorced from the current laws and circumstances…” the motion states.

The motion notes the adoption of a new accountability model, the Read to Achieve Program, and changes in the support of at-risk students as some of the ways education in the state has changed.

Cobey said the State Board has been working on meeting the requirements of Leandro for years and that he thinks the suit should be dismissed. He noted that the Board has implemented the Whole School, Whole Community, Whole Child (WSCC) Model, something it told the court the State Board would do.

“It’s a comprehensive approach to each child from the time they come into the world until they get through K-12 education, and I think that’s our best hope,” he said.

Update: The attorney for the State Board provided the following statement via e-mail: “The public school system in North Carolina has changed significantly since the original Leandro lawsuit was filed over two decades ago in 1994. North Carolina has a refined accountability model; reformed and rigorous curriculum standards; increased graduation rates; increased career and technical education opportunities; an enhanced digital infrastructure that includes the North Carolina Virtual Public School; more comprehensive programs and supports for identifying and serving at-risk students; new programs and supports for improving educator effectiveness; and the State Board of Education’s implementation of the Whole School, Whole Community, Whole Child model. What has not changed during the past two decades is the State Board of Education’s commitment to educating all NC public school children for the future.”

Mark Dorosin, an attorney from the UNC Center for Civil Rights working on the Leandro case, said the center plans to oppose the Board’s motion. In 2005, the Center started representing parents and students in the Charlotte-Mecklenburg school system and the Charlotte-Mecklenburg NAACP in the Leandro case.

The Leandro case started in 1994 when families from five low-wealth counties sued the state, claiming it wasn’t providing their kids with the same educational opportunities as students in better-off districts. In 1997, the Supreme Court ruled unanimously in the case that the state’s children have a fundamental right to the “opportunity to receive a sound basic education.”

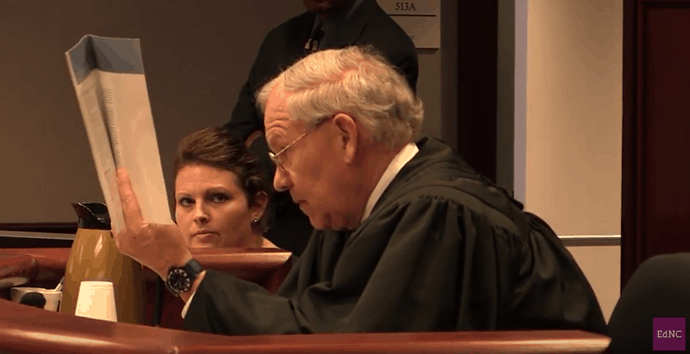

For decades, the Leandro case was overseen by Judge Howard Manning. In October of 2016, he requested to be removed from the case and Chief Justice Mark Martin reassigned it to Emergency Superior Court Judge David Lee.

Through an executive order last Friday, Governor Roy Cooper also created a Commission on Access to Sound Basic Education, comprised of 17 members appointed by the governor, to work “in conjunction” with the consultant and come up with strategies to meet the Leandro requirements set out in the court’s final judgment in 2002.

“No matter where North Carolina students live or go to school in our state, they all deserve access to a quality education that prepares them for the jobs and opportunities of the future,” Governor Cooper said in a statement. “That is their right as children of North Carolina and we must not let them down.”

The requirements that the court ruled are needed to meet its obligation of providing “a sound basic education” include:

- “A ‘competent, certified, well-trained teacher who is teaching the standard course of study’ in every classroom;

- A ‘well-trained competent principal with the leadership skills and ability to hire and retain competent, certified and well-trained teachers’ in every school; and

- The ‘resources necessary to support the effective instructional program’ in every school ‘so that the educational needs of all children, including at-risk children, to have an equal opportunity to obtain a sound basic education, can be met.'”

Although the governor’s commission and the consultant are instructed by the court to cooperate with each other, the commission, according to the court’s proposed order, must create its own report, released within 45 days of the consultant’s final recommendations.

During the development of the plan, the independent consultant has access to any of the commission’s meetings and findings. The consultant must share information with the commission “upon reasonable request.”

The purpose of both reports is to help the parties draft a consent order for the court’s consideration, which must be submitted within 60 days after the commission’s report comes out.

The plaintiffs and state have until October 30 to agree on an independent consultant. If they do not meet the deadline, each side can submit up to three nominations and the court will choose from those nominees.

In the four months following its appointment, the consultant has to share with both parties its preliminary recommendations on steps the state should immediately implement with both parties, the governor’s commission, and the court.

In the year following its appointment, the consultant’s final recommendations are due — which should help the state “achieve sustained compliance” with the court’s above mandates.

The commission plans to seek funding through private sources to help mitigate the cost of the commission and the consultant.

Editor’s Note: Judge David Lee is the father of EducationNC Content Director and Managing Editor Laura Lee

Recommended reading