|

|

Highlights

- Teacher supply is not a one-size-fits-all problem, nor is there a one-size-fits-all solution.

- It is important to understand statewide teacher supply trends and to address the drivers of those trends, but it is just as important to understand whether teacher supply is healthy, adequate, or stressed district to district.

- All districts should be striving for 0% vacancies on the 40th day of school this year.

- On the heels of student learning loss during the pandemic, now is not the time for vacancies that will impact student achievement.

- Teacher supply is a localized challenge that deserves the attention of the state, and not just at the start of school.

Crisis is not my favorite word. It is used too often to grab attention at the expense of the thoughtful policy solutions our students, schools, and state deserve. It also ignores that most policy issues play out differently in different classrooms, schools, and districts across our state.

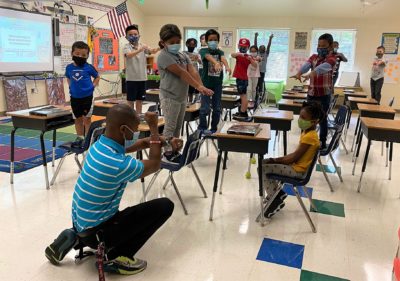

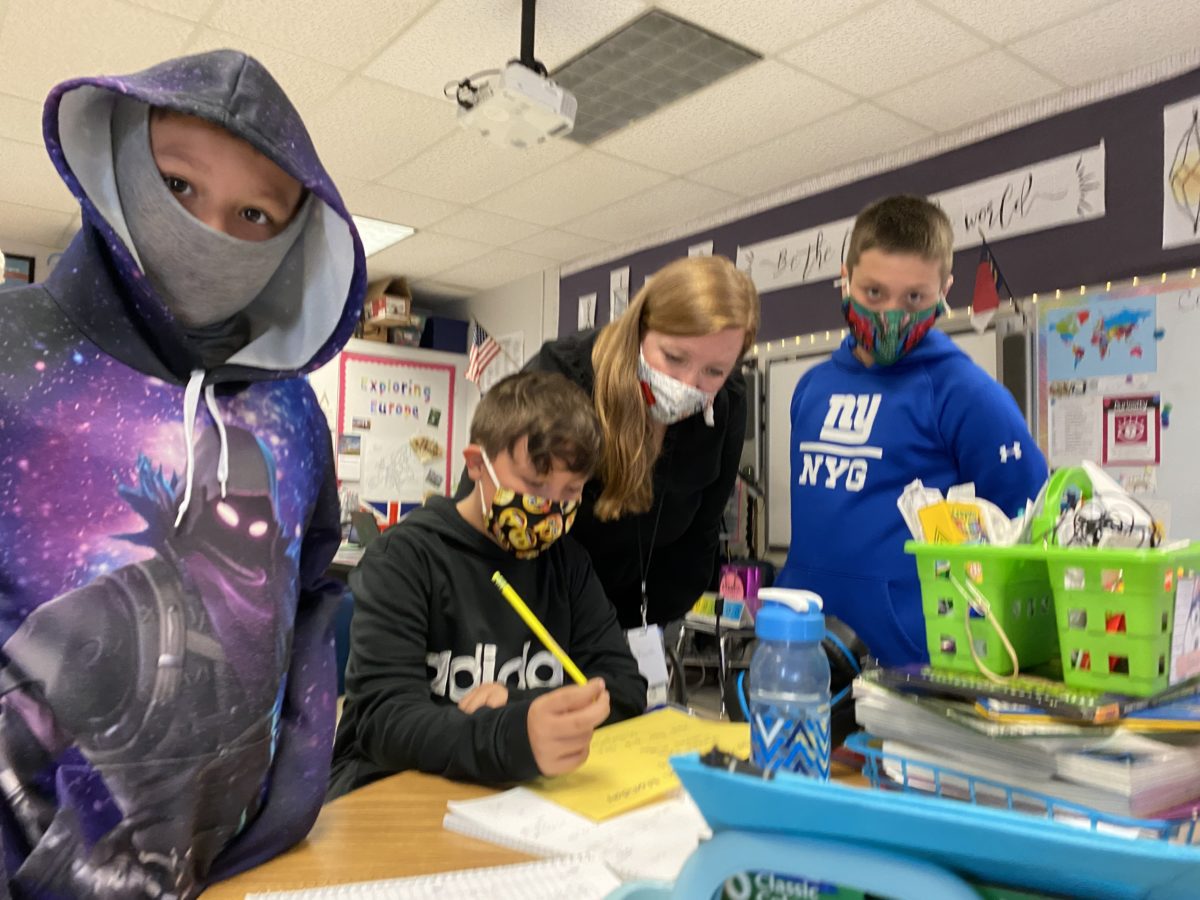

On the other hand, if you are sitting in a classroom on the first day of school and there is no teacher, it’s a crisis. It will be especially so if there is still no teacher on the 4oth day of school.

I wrote that five years ago at the start of school in 2017, way before the pandemic.

This year, headlines designed to scare seem to be everywhere. A newsletter from Politico led with, “The teacher shortage problem is bad. Really bad.”

The Washington Post led with, “‘Never seen it this bad.’ America faces catastrophic teacher shortage.”

Last week as I sat at a dealership in the mountains getting my car serviced, a parent overheard a television broadcast about teacher vacancies in Charlotte. She pondered out loud whether she should move her child to a different school, even though she lives in a mountain county with only a handful of vacancies, far from that metro area.

Alexander Russo, who provides independent analysis of media coverage of education, enlisted the help of RAND experts urging the media to improve coverage on this issue. The researchers found: “For two years, news articles have been warning of an impending ‘mass exodus’ of K-12 public school teachers and principals, which could leave schools scrambling to fill positions.” That article led with “teacher shortage stories are all wrong” and goes on to make recommendations to improve them.

A more nuanced analysis was needed back in 2017 — see our EdExplainer and research on the supply and demand cycle from back then — and it is needed now. It is important to understand statewide trends and to address the drivers of those trends, but it is just as important to understand whether teacher supply is healthy, adequate, or stressed district to district.

What we know about vacancies

Jack Hoke is the executive director of the N.C. School Superintendents’ Association. He collects data from the superintendents about this time each year to find out where districts stand on vacancies.

Statewide, vacancies are up since this time last year. In the 98 of 115 districts included in Hoke’s analysis, overall vacancies went from 7,638 to 9,677.

Breaking that down, vacancies went: from 954 to 1,570 in elementary schools; from 672 to 1,023 in middle schools; from 728 to 1,024 in high schools.

Beyond the classroom: from 253 to 354 for counselors, social workers, and psychologists; from 3,900 to 4,364 for classified positions; from 1,131 to 1,342 for bus drivers.

This year's analysis included data categories that were not included in last year's totals — namely assistant principals, with 70 vacancies; central office staff, with 698 vacancies; and EC teachers, with 850 vacancies. That's a total of 1,618 additional vacancies. The overall number of vacancies mentioned above — 9,677 — does not take these into account to accurately compare this year's data with last year's.

That's a lot, but remember it's statewide data that includes more than just classroom teachers, and it is for almost 2,500 schools and about 95,000 teacher positions.

Also, Hoke confirmed eight districts have 0-1 vacancy; 29 districts have 2-10 vacancies; 23 districts have 11-20 vacancies; and 21 districts have 21-50 vacancies.

That means 81 districts are dealing with fewer than 50 vacancies.

Just 17 districts in Hoke’s analysis have more than 50 vacancies. Importantly, whether these numbers are a lot depends on the size of the district.

Much of North Carolina’s supply and demand issue has to do with the distribution of teachers across our state relative to shortages driven by geography, by challenges of particular schools, and by area of teacher specialization.

Superintendent Jeff McDaris in Transylvania County Schools filled his last licensed classroom position on Friday. He says, "We are OK."

Differentiating statewide and local attrition trends

Our state changed how we define and report attrition – how many people are leaving the teaching profession – in 2015-16. Data prior to that year are not comparable.

Here are the statewide attrition rates since the change in methodology: 9.04% in 2015-16, 8.70% in 2016-17, 8.1% in 2017-18, 7.50% in 2018-19, 7.53% in 2019-20, and 8.20% in 2020-21. Compared with 2015-16 and 2016-17, even in the pandemic, the attrition trend is down.

The 2020-21 report was released in February 2022, so we won’t have 2021-22 data for a while. But at that point in time, the lead key finding was, “Generally, North Carolina teachers are remaining in the classroom.” It also found that attrition was comparable to other industries.

In 2020-21, there were 3,800 teacher vacancies statewide on the first day of school and 3,217 on the 40th day of school (3.43%), according to the report. That’s the number to look for year to year. That’s the number to really worry about.

These data are a good way to get a handle on regional and local trends in teacher supply. In 2020-21, of our 94,342 teachers, 7,736 left the profession, and the attrition rate ranged from a low of 7.6% in western North Carolina to 9.2% in southeastern North Carolina. If you look at the data district by district, attrition ranges from a low of 2.4% in Elkin City Schools to a high of 26.1% in Northampton County Schools.

Note that mobility is different from attrition. Mobility is “the relocation of an employee from one LEA/charter school to another within the state of North Carolina.” Often if teachers are unhappy, they change schools or districts instead of leaving the profession.

What drives vacancies and attrition?

Our public school districts are the largest employer in many of our counties. They, like all large employers, are used to not being fully staffed all the time. I worry most about bus driver, classroom teacher, and principal vacancies. Those vacancies create real pain points for students and parents.

On the heels of student learning loss during the pandemic — well documented by the N.C. Department of Public Instruction — now is not the time for vacancies that will impact student achievement.

Attrition is often highest over the summer months, and mid-school year departures remain unusual, though one human resources director told me they are on the rise in some districts. Often just after spring break, superintendents survey their teaching corps to get a sense of turnover. Those surveys inform recruitment and retention strategies for the school year ahead.

Superintendent Scott Elliott in Watauga County Schools started hiring in March and kept hiring all summer long. As school starts Monday, he is just shy one teacher, a surprise vacancy that happened the day before the start of school when a teacher decided to relocate to be closer to a family member.

As we travel, we assess whether teacher supply is healthy, adequate, or stressed. Over time, we've found that the following drivers are important district to district:

- salaries and compensation,

- teacher preparation and entry,

- hiring and personnel management,

- induction and early-career support for teachers, and

- working conditions.

Additional factors we consider include: effective management at the school and district level; a strong culture at the school and district level; enrollment changes; whether the district is low performing; the age of teachers (older teachers are less mobile, younger teachers are more mobile); proximity to educator preparation programs; urban, suburban, and rural relative job opportunity; and the capacity of districts to diversify the workforce.

It is not and has never been just about the money.

Within districts we look to see if the vacancies are evenly distributed across schools or concentrated.

We always expect to see higher vacancies in elementary schools because there are more elementary schools.

We expect to see higher vacancies in hard-to-staff subjects like STEM and exceptional children.

More recently, we have noticed pandemic impacts, including districts offering large signing bonuses, new positions funded with federal dollars, and industry specifically recruiting teachers as the labor market has tightened especially in urban areas.

From surveys to history to politics, context matters

Other outlets are reporting that the 2022 Teacher Working Conditions Survey found that 7.22% of teachers responding to the survey indicated they planned to leave education entirely compared to 3.98% in 2020. To look at the survey yourself, go here, on the right of the page under state reports click individual item analysis, then scroll to question 10.1.

While that is true, the RAND experts note, “The danger of relying on teachers’ and principals’ self-reported intentions to leave their jobs is that they overestimate actual turnover.” Vacancy and attrition data is a better measure of what’s happening with teacher supply.

And, remember, this issue is not new.

The N.C. Center for Public Policy Research studied our supply of teachers for almost all of its more than 40 years, finding over and over again starting in the 1980s the need for “a labor pool filled with well-qualified teachers thoroughly prepared for the demands of today’s and tomorrow’s classroom, and retention and placement efforts strong enough that teachers stay on the job.” There were high water marks for attrition in 2000-01 and 2014-15.

That Politico newsletter did note that it is important to think about both teacher supply and teacher demand. “On the demand side,” it said, “we need to be thinking about issues related to the politicization of the field.” If our schools become political battlegrounds, it will exacerbate the problem.

In a recent article in the Watauga Democrat, Elliott said, “Many teachers are leaving our profession because they don’t feel supported or appreciated, including by parents.”

“There are some people out there who are trying hard to cultivate this division through politics, but we can prevent that from happening here. When parents get to know the teachers and have open communication and mutual respect, we can work through anything. It’s all about relationships.”

We will be watching the school elections this fall to see what happens with attrition in the districts where the races are the most contentious.

Crisis in the classroom

Mary Ann Wolf, the executive director of the Public School Forum of North Carolina, recently called attention to the districts where teacher supply is stressed, saying:

“Public school districts across the state are struggling with skyrocketing teacher vacancies and a dearth of candidates to fill critical positions.

This is a problem that has been escalating for many years. Enrollment in colleges of education is down by 50% over the last decade. Many teachers leave classrooms after only a couple of years in the profession. Still others are retiring earlier than in the past.”

Classrooms without teachers present a crisis. As the state of the teaching report aptly warns, “With nearly a quarter of the school year complete by the 40th instructional day, there will likely be a negative effect on the academic achievement of the students in these classrooms.”

On the heels of student learning loss during the pandemic — well documented by the N.C. Department of Public Instruction — now is not the time for vacancies that will impact student achievement. And some of the strategies districts have used in the past to cope with vacancies — having teachers teach outside their expertise and increasing class size, for example — should be off the table under the circumstances.

For districts where teacher supply is stressed, the push to find qualified teachers for classrooms must extend beyond the first day of school.

It's a localized challenge that deserves the attention of the state and not just at the start of school.

Bridging the gap

Back in March 2022, the superintendents had a conversation about innovative ways to bridge the gap in the labor force.

Ron Hetrick, a labor economist with Lightcast, walked the superintendents through ways they can engage people on the sidelines, focusing on career paths, culture, remote and part-time options, and what motivates younger and older cohorts of the workforce.

He suggested designing processes to shorten the hiring process, quicken onboarding and training, and providing or assisting with child care costs.

He also suggested that districts focus on specific groups of untapped talent, like veterans, caregivers, and post retirees.

Our collective goal should be to have way more than four districts with 0% vacancies on the 40th day of school this year.

While this isn't just about money, the state does have money. Here is the latest state controller's report. The state actually collected almost $500 million more than budgeted through the end of June.

In districts where high levels of vacancies are predicted on the 40th day of school, it is time to get proactive and creative at the local level with state support.

In the most recent state of the teaching profession report, just four districts had 0% vacancies on the 40th day of school: Polk County Schools, Graham County Schools, Rowan-Salisbury Schools, and Weldon City Schools. What I notice about that list is that in all of those districts, the relationships with the labor force is really tight. Leaders know who is available, where to find them, and what will incentivize them to come back into the classroom.

Our collective goal should be to have way more than four districts with 0% vacancies on the 40th day of school this year.

The Politico article rightly says that everyone has a role here. Philanthropies should consider funding some quick pilots in districts under stress. DPI should provide guidance. Our educator preparation programs should weigh in with just-in-time solutions. Lighthouse or other consultants should be brought in as needed.

When Hetrick was presenting to the superintendents, he urged them to develop strategies for the now, the near future, and the future. I remembered the state allowing state employees to take time to fill immediate gaps in districts during the omicron surge. I could imagine public-private partnerships where industry loaned workers to schools to teach a class — a strategy we saw Foothills Community School using as a recruitment strategy. Recently, educators in the Education Policy Fellows Program analyzed the geographic spread of our North Carolina Teaching Fellows, finding 54 counties had none and 40% of fellows came from one region. Successful grow-your-own programs need to be replicated especially in districts that are stressed.

An article this week in K-12 DIVE highlights financial incentives districts across the country are trying, but also notes these outside-the-box solutions:

"Arizona, for example, is allowing teachers without a bachelor’s degree to lead classrooms while they work toward their higher education degrees. Florida is not requiring bachelor’s degrees for military personnel and veterans who want to teach as long as they meet certain conditions. And in January, Tennessee became the first state to have a permanent registered teacher apprenticeship program approved by the U.S. Department of Labor."

Please let us know what you are trying and what is working at the local level so we can share your promising practices with districts across North Carolina. And to all of our educators choosing to serve in our classrooms, schools, and districts, thank you.

This is not a one-size-fits-all problem, nor is there a one-size-fits-all solution. We are going to have to work together to get teachers in front of all of our students.

Recommended reading