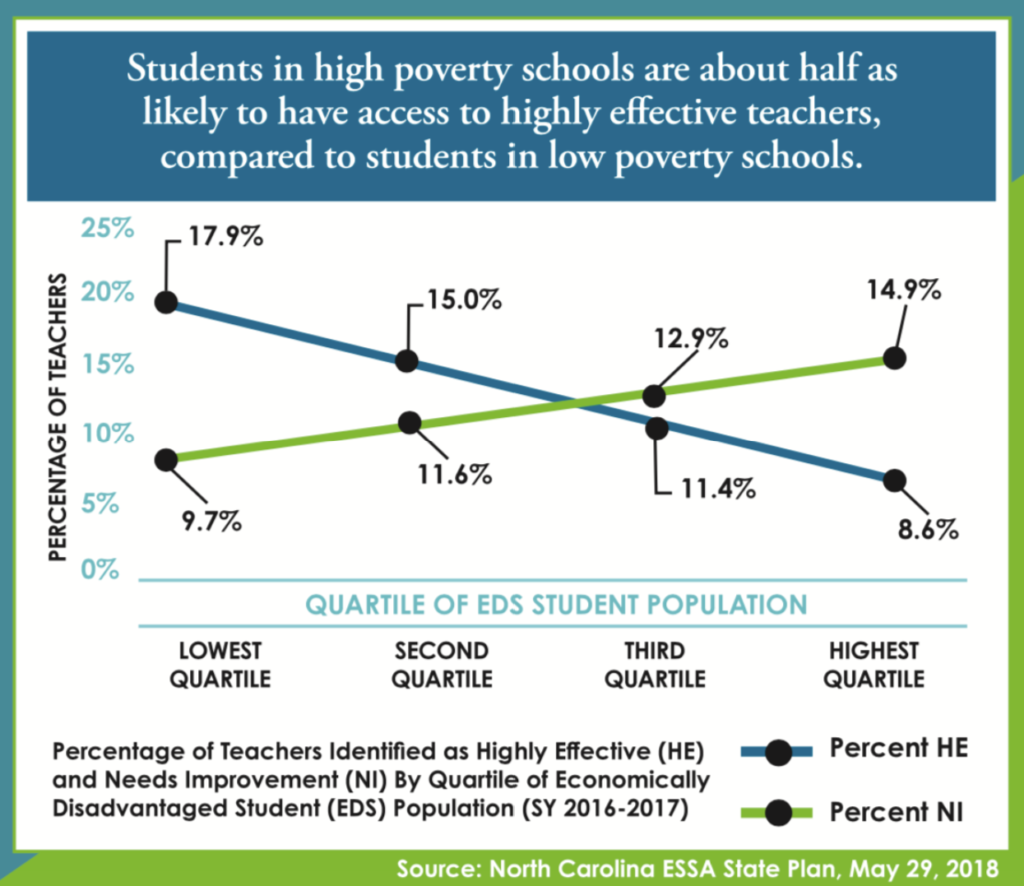

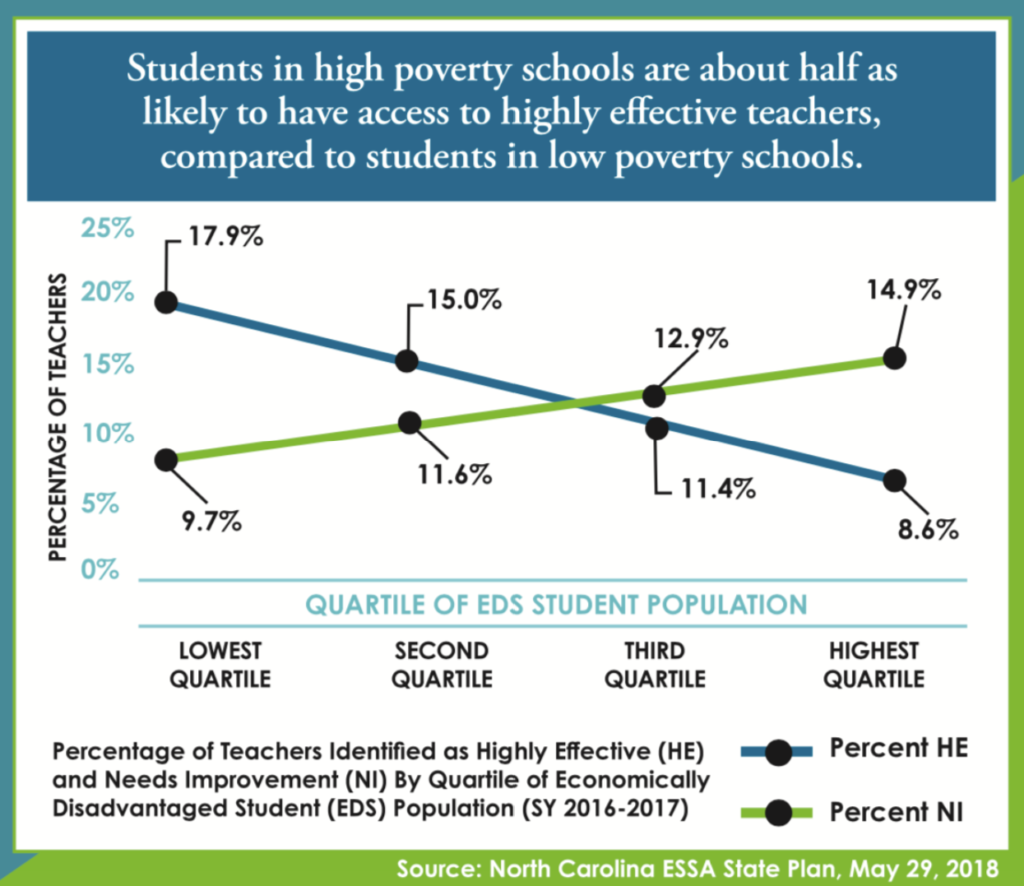

“Students in high-poverty schools are about half as likely to have access to highly effective teachers, compared to students in low-poverty schools,” said Johanna Anderson, executive director of The Belk Foundation, at a recent convening of their board of directors and education stakeholders.

This is not a new data point, but strategies are emerging to address it given vacancies in local labor markets for those working in schools and districts, and an initiative to redesign teacher licensure, support, advancement, and pay structures in North Carolina.

Calling for more on-ramps into the teaching profession, state Superintendent Catherine Truitt said, “Opening these doors into the profession for our teachers can turn into opening the doors of opportunity for our students.”

This policy conversation is not just about more teachers, it is about more effective teachers and whether they end up in the classrooms and schools that need them most.

A lesson in local supply and demand

Although often talked about on the statewide or even the national level, labor markets for teachers tend to be local and regional. Teachers work close enough to where they live that they can drive to school each day.

In North Carolina, during the 2020-21 school year, teacher attrition (those leaving the profession) was up only slightly and teacher mobility (those moving among districts) was down compared to the previous three school years. We are all holding our collective breath to see if that holds true for 2021-22.

And while teacher vacancies appear to be up, the N.C. Department of Public Instructions says it could be because of an increase in the number of positions given the influx of federal funding.

But statewide data often masks labor market challenges at the school and district level.

Getting more specific about the trends in teacher recruitment and retention and focusing on “pinchpoints” is important to finding solutions that increase access to effective teachers, said Dr. Dan Goldhaber, director of the Center for Analysis of Longitudinal Data in Education Research (CALDER), speaking to the Belk Foundation board and stakeholders. Goldhaber’s research looks at shortages driven by geography, challenges of particular schools, and by area of teacher specialization.

Recently, North Carolina’s report on the state of the teaching profession in 2020-21 was released.

The report identifies geographic differences across the state. For instance, the teacher attrition rate ranges from a low of 2.4% in Elkin City Schools to a high of 26.1% in Northampton County Schools, and the teacher vacancy rate ranges from 0.0% in Polk County Schools and Graham County Schools to 22.6% in Bladen County Schools.

In North Carolina, “there does not appear to be a strong association between teacher attrition, mobility, and recoupment rates and designation as a low-performing district,” according to the report.

Whether the teachers that replace teachers lost through attrition or mobility are as effective remains unanswered, according to the report.

North Carolina is changing how the state assesses the most difficult-to-staff license areas. Instead of asking school districts their impressions of which licensure areas are hardest to staff, districts are now asked to report on teacher vacancies on the first and 40th instructional day of the 2020-2021 school year to ground the inquiry in data instead of the perceptions of recruiters.

For the 2020-21 school year, school districts in North Carolina reported a total of 93,369.51 teaching positions, and there were 3,215.94 (3.4%) vacancies on the 40th instructional day.

It comes as no surprise that elementary schools have the greatest number of vacancies since there are far more elementary schools than middle or high schools, but a vacancy in a classroom is a vacancy in a classroom with the impact felt by the students. STEM and special education remain difficult to staff across the education continuum in North Carolina.

Where teachers learn to be teachers matters

Goldhaber said student teaching can be a lever for addressing labor market shortages. He notes a couple of lessons learned.

Student teachers who get experience in classrooms with students that “mirror” the classrooms they will end up teaching in are more effective.

And student and beginning teachers with access to a highly effective mentor are much more effective — it’s basically the equivalent of having two years of teaching experience.

Goldhaber noted that proximity between teacher preparation programs and districts is a key factor in the statewide distribution of effective teachers and mentors, and this can impact student’s access to effective teachers.

Previous research by the Education Policy Initiative at Carolina (EPIC) — also funded by the Belk Foundation — found “students win when there is a close coordination between school districts and colleges of education, especially as it relates to classroom placements and hiring practices.”

The 58 community colleges across North Carolina are beginning to offer associate degrees in teaching, and they could play an increasingly important role in addressing the issue of access to effective teachers given their proximity to many more school districts. Goldhaber said that will depend on how well teachers are taught to teach.

John R. Belk, board chair of the foundation, said mentor educators should be sought out and paid more for the impact they have on preparing new teachers.

“Dr. Goldhaber challenged us to scrutinize the data to make smarter policy decisions about the teacher pipeline,” said Belk. “Generalizations about shortages aren’t productive. As a state, we need to pay attention to finer grain data on high-need areas like STEM and special education, and make sure our strategies match the demand.”

When it comes to access to effective teachers, Meghan Harris, a multi-classroom leader at Governor’s Village STEM Academy in the Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools, highlighted the need to support teachers holistically.

“The relationship piece,” she said, “is one of the biggest areas I am noticing that our teachers that are new to the profession need a lot of support with. We are very much a customer service business — our students are our clients, our parents and community are our clients — so what we are doing is we are trying to build relationships in order to then be able effectively teach them.”

Headwinds and opportunities

These discussions on equitable access to effective teachers took place during the retreat of the Board of Directors of The Belk Foundation recently in Charlotte.

The webinar with stakeholders, held on Feb. 23, explored headwinds and opportunities as the state strives to ensure equitable access to effective teachers, a component of the foundation’s strategic plan. The more than 300 people registered included principals, superintendents, local and state school board members, staff of the N.C. Department of Public Instruction, legislators, leaders from community colleges and colleges of education, nonprofit leaders, and philanthropists.

Truitt presented opening remarks, and Goldhaber presented the keynote address. Dr. Alison Welcher, a board member of The Belk Foundation and senior vice president at Public Impact, moderated a panel discussion, including Harris; Dr. Paul Fitchett, assistant dean of teaching and innovation at the Cato College of Education, UNC Charlotte; and Monique Perry-Graves, executive director, Teach for America North Carolina.

“We, at The Belk Foundation, are always seeking ways to understand what is working in schools and districts across the state. We are delighted to convene a panel of leaders focused on training and retaining our top teacher talent,” said Belk, the chair of the board.

Please watch and share the webinar. The panel discussion begins at 31:40.

Editor’s Note: The Belk Foundation supports the work of EdNC.