Ken Outlaw’s goal was to graduate community college with a 4.0 grade point average. He wanted to make up for one of the biggest mistakes of his life — dropping out of high school. He wanted to show his family, and especially his special needs stepdaughter, that it was possible. He wanted to show future employers his potential.

Working the night shift, and accommodating extra hours requests from his employer, the task was never an easy one.

He got home at 2 a.m. and went to bed. With his 4.0 goal firmly in mind, he set an alarm for 6 a.m. to prepare for school. At 7 a.m., he headed to classes at James Sprunt Community College in Kenansville, N.C. and, after the school day, went back to work before arriving home again. Exhausted. Weary. At two hours past midnight.

“It was a lot, but I’m not afraid of working hard,” Outlaw said. “At the time, I was thinking it would all be worth it to create a better life for my family.”

There were times he was sure he would break. His resolve was strong, but on four hours’ sleep he was holding on by a thread to dreams of graduating with that perfect GPA, getting his welding degree and improving his family’s situation.

Then Hurricane Florence hit. And that thread was ready to snap.

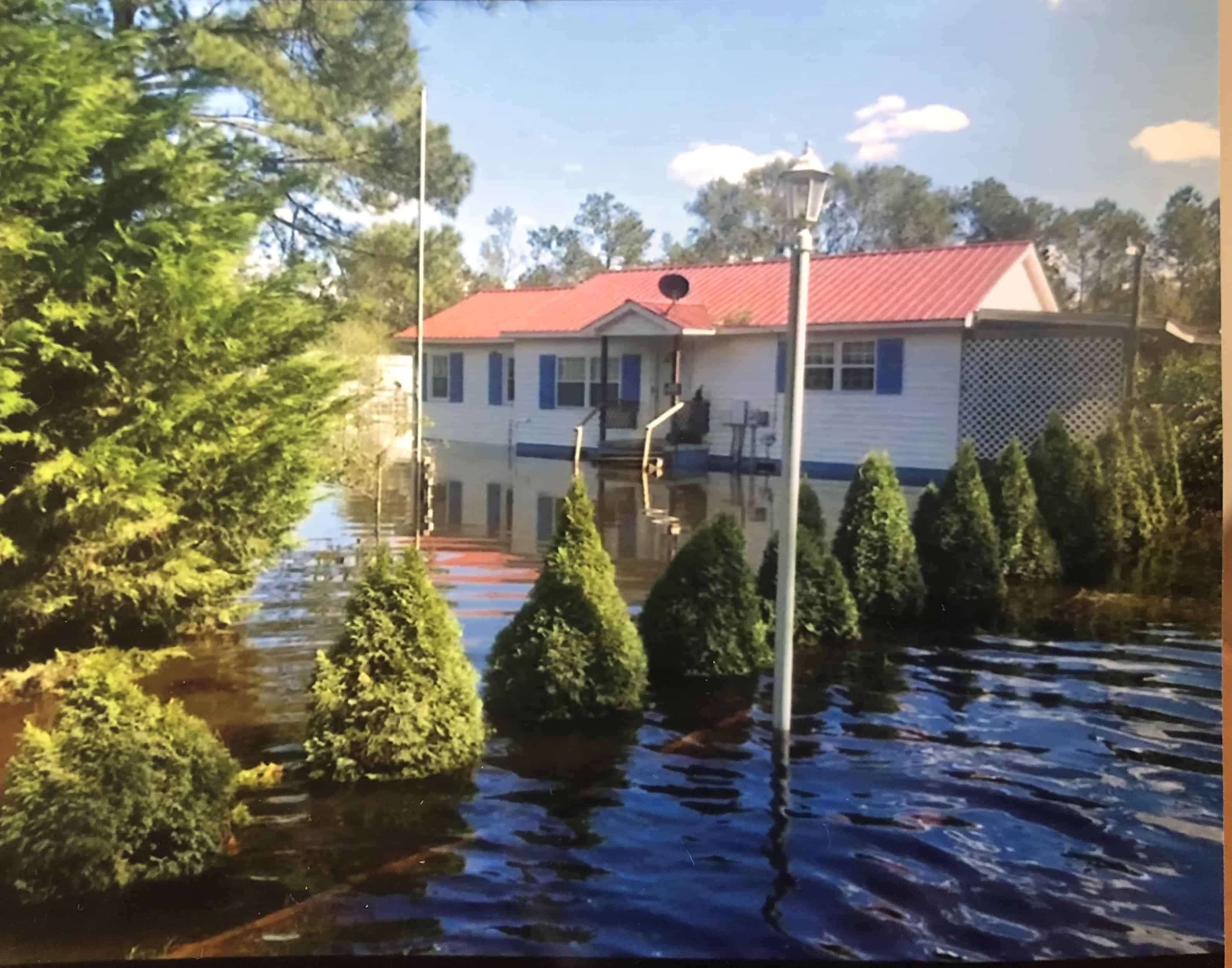

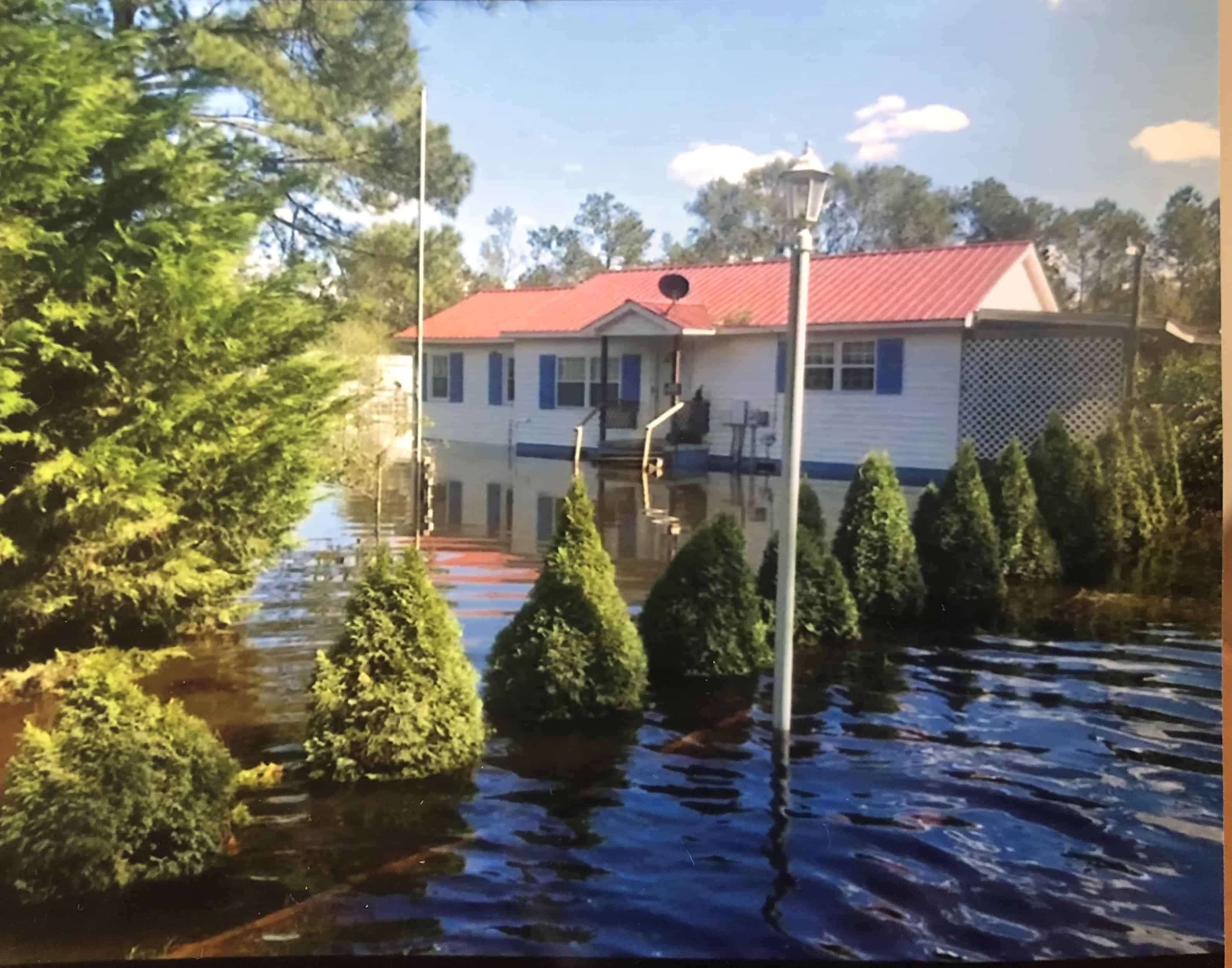

He saw water rise like an ocean around his home, swallowing up his front porch and flowing inside more than four feet high in the bedroom. His house stood, inaccessible, like an island in the middle of North Carolina farmland.

A community college degree can mean up to 55% higher earning potential for certain graduates, according to North Carolina’s Department of Commerce. For Eastern North Carolina residents, living in mostly rural towns with declining industry and opportunity, community colleges offer hope for earners struggling to make ends meet. For the communities, the colleges and its students help attract new businesses and represent hope for rebuilding local economies.

But with increasingly frequent climate disasters – like three, 500-year floods visiting in just three years — the already fragile hopes of Eastern North Carolina community college students are strained further, forcing students to balance dreams of college diplomas with meeting basic security needs, such as housing and food.

For Outlaw, the flood left him desperately scrambling for time and money to save his home. He looked into the eyes of his family and outwardly wondered if he had the capacity to shelter them and keep food on the table while completing his degree.

He wasn’t the only one.

Community colleges offer ladders of opportunity

Ginger Jenkins didn’t expect to attend community college. She had a fine career in accounting, learning on the job for about 20 years. But her pay was maxed out and one day she was told she was no longer needed. The company laid Jenkins off. That’s when she realized her experience met the requirements on many job postings, but her education did not.

“That was a wakeup call,” she said.

Most times, living in North Carolina can provide an easy fix for that.

North Carolina’s community college system is the third largest in the nation, with more than 700,000 students enrolled in 58 colleges this year. Its infrastructure is so vast it boasts that no resident can drive 30 miles without passing one of its institutions. And it’s among the nation’s most affordable, running less than $2,000 a year for full-time, in-state tuition.

The state’s governor, Roy Cooper, often links the health of North Carolina’s economy to its community colleges – and it’s a natural link, considering that 40 percent of North Carolina wage earners attended some community college within the past 10 years.

Those students often have had to surmount significant obstacles, even before the recent influx of extreme weather. Over half of all undergraduates live at home to make their degrees more affordable, and 40 percent of students work at least 30 hours a week. About 25 percent work full-time and go to school full-time.

The typical college student is not fresh out of high school. A quarter of community college students are older than 25, and about the same number are single parents. A recent report found just having basic sustenance was a challenge for many community college students, with nearly half of respondents reporting some level of food insecurity.

Jenkins fit the single parent data point. She’s also older than 25 and works full-time. After she was laid off, though, she became determined not to fall in the food insecure category – but she had four mouths to feed and was caring for an aging father.

The first priority was finding shelter

Like Outlaw, Jenkins enrolled at Sprunt hoping to make life just a little bit easier for her family.

She lived with her four kids one town over from Outlaw, in a cozy home in Wallace about a mile northeast of the Cape Fear River. Her father lived next door.

She balanced her community college workload with caring for her children, all in middle or high school. Late nights and early mornings were the norm before Florence’s arrival. She had grown accustomed to the daily urgencies, always thinking about the next item on her to-do list.

Drop the kids off at school. Check.

Head to Sprunt and put in some hours in their tax office. Check.

Classes. Study. Check.

Part-time substitute teaching for extra money. Check.

Pick up the kids and help with homework. Check.

Settle in for a long night of studying for her own classes. Check.

Then, last September, Jenkins and her family lost just about everything they owned when Hurricane Florence hit. They took two weeks’ worth of clothes with them, at the most, when they evacuated. When they came back, there was nothing else left.

The river waters came up so high that, when they started gutting the house, they removed entire sections of walls and floors without finding salvageable wood or dry wall.

The home was a complete loss. With the help of family and friends, they demolished it. Now, all that remains is a faint outline of where it once stood, filled in with overgrown grass and weeds.

“My kids didn’t understand what had really happened with the storm until they saw the house being torn down,” she said. “It was like they realized, they used to have this or that, and now they don’t have those things.”

Homeless, her first priority was finding shelter. They found a rental, smaller than their house but big enough for the family to fit. But it would be more than a month before Duplin County Schools re-opened, so her next challenge was figuring out how to balance caring for them, working, and tending to disaster recovery.

Oh, and school.

“She didn’t know if she could balance it all,” said Amber Dail, an instructor at Sprunt whose kids go to school with Jenkins’s. “I just couldn’t imagine dealing with everything she was going through. It was so sad and just so tough.”

Jenkins would sit for hours thinking about what to do. She had a job. Plenty of experience. She wanted to graduate, but more than anything she knew her family needed her. They needed a home. They needed a plan to rebuild that left money for food on the table. And her children needed attention and help catching up after 30 days of missed class time.

Could she really afford to graduate anymore?

Students see their resiliency tested

The same question plagued thousands of community college students in North Carolina’s coastal and inner coastal region – a broad collection of tourist and working-class towns. Outlaw mulled that question for weeks. It was a much more difficult question than starting community college in the first place.

Outlaw grew up in Eastern North Carolina, the product of a working-class family. He struggled in math and didn’t enjoy high school. Eventually, the lure of ending arithmetical struggles and earning money became too strong. He dropped out in ninth grade.

“It was one of the biggest mistakes I made,” he says now. “My heart goes out to anyone who left school, because I know just how hard it is when you make that decision.”

Outlaw took minimum wage jobs and worked hard to support himself. He married and later started his own towing business. When they saved up some money, he and his wife started looking for a home. Like many young couples, they made a list of all the things their dream house would offer. They wanted a comfortable sanctuary in the country; some place he could grow fruit trees.

They moved into a secluded, single-story home in Beulaville, just 10 miles down the road from Kenansville and two miles west of the river. They started a grapevine and grew apples, pears, peaches and figs.

But as the years waned, Outlaw realized dropping out placed a harsh ceiling on his earning potential. He had gotten his GED some 12 years after dropping out, but now he was becoming increasingly committed to correcting course on a career track, hoping to learn a good trade and provide a little more financial security as the breadwinner for his family.

“I just remember thinking, I’m not getting any younger,” he said. “I really didn’t want to wait any longer.”

So he sold the only business asset he had – his tow truck – and set aside money for community college. Between the money for the truck, odd jobs he picked up here and there, and some financial aid, he was able to start his community college journey.

“We didn’t live great,” he said, “but our bills were paid on time and we had food in the house. I was cutting grass, I was trimming trees, hauling off trash, picking up scrap metal – any kind of odd job I could do.”

When Outlaw enrolled at Sprunt, he set a goal for himself, and he shared it with his family. He would work. He would support his family. And he would overcome his math struggles. He would earn straight A’s.

“It was important because I wanted my stepdaughter to see that,” he said. “That you can accomplish something like that if you set your mind to it.”

He knew math would be a challenge. Proactively, he worked with counselors at Sprunt and secured a tutor who helped him with extra math practice. Outlaw was on track with his goal through his first three semesters, earning A’s in every class, boasting perfect attendance and landing reliably on the President’s List each semester. All the while, he found time during the day to volunteer through the college’s Spartan Table program, a food pantry that makes sure students in need don’t go hungry.

As he started his final semester at Sprunt, Outlaw got an entry-level job as a welder through contacts he made at the college. He started making steady pay for the first time in years, finally putting a little distance between income and expenses.

“We were seeing the light at the end of the tunnel after all this time in school not having a steady income,” he said. “We’re finally getting some money and then – bam – Florence hits us.”

Just one month after he started welding.

When the reports of flooding threats rolled in alongside the storm, Outlaw prepared for the worst he could imagine– but his imagination fell short of reality.

Outlaw’s family evacuated to Potters Hill ahead of the hurricane. He wasn’t far behind, but he waited until the very last minute so he could keep the power on as long as possible – eager to save the contents of his refrigerator and freezer. When he left, the road outside his home was already halfway flooded.

After the storm winds died down, he took a chainsaw and cut his way through trees to visit the house.

“No water was at the house when I got there,” he said, “but I knew that water was rising and that more was coming.”

He headed back to Potters Hill and his family. It was weeks before he could return to his home. In fact, he had no idea how his house fared until the fire department visited his street by boat to take pictures of flooded homes. Outlaw’s neighbor tagged him in one of the posted photos. He had no idea what to expect.

What would it have mattered if he did? Hardly anyone would have been prepared for what he saw.

“My heart just dropped,” he said. “We knew then that we had a lot of damage to deal with.”

Water had infiltrated and sat in his house for weeks. The home was a total loss. The Outlaws were able to salvage a few things – photos that were high up on the wall, his stepdaughter’s medicine from a cabinet, a few tools. Everything else had to be thrown out to the roadside: furniture, beds, appliances, memories.

Everything.

Everything in perspective

“It is almost as if we are starting over as young kids again, starting out on our own,” he said in the months that followed. “This hurts, but life goes on. This storm has put everything in perspective for me. I was able to save my family and that is all that matters.”

It’s often all that matters in the wake of disaster. Florence claimed more than 40 lives in North Carolina. Nine of those lives were lost in Duplin County, where Outlaw and Jenkins live. Inevitably, though, after the relief of surviving passes, the reality of what’s been lost settles in. For Outlaw, that was a couple weeks after the flooding claimed his home. He was living in the parsonage of his church, which was offered to him and his family indefinitely.

“They offered us a place to live for free, they were so generous,” Outlaw said. “But we didn’t want to inconvenience them. Somebody else might need it.”

Homeless – literally – and worried about others’ needs. Glimpses of Outlaw’s humility and concern for others aren’t rare. But this example was certainly remarkable. Especially considering the family had just gotten word they wouldn’t qualify for a FEMA-provided camper when he made the decision to move out.

He scraped together what he could in order to meet the unexpected expense of finding temporary shelter, buying a used 31-foot camper and parking it in his storm-ravaged backyard. He moved in with his wife, adult stepdaughter and three inside dogs.

After classes resumed at Sprunt, Outlaw remained busy working with FEMA fighting for help. He would meet church volunteers as they helped to muck and gut the home. He met with contractors to understand the cost of restoring his home. After work, he would lie on the bed in the back of his cramped trailer and study on his cell phone – because without WiFi access his laptop was no help.

Just outside the room, he could hear the three dogs, his wife and his stepdaughter. He tried to concentrate, but in the back of his mind was fear that the muggy conditions or stress might bring on his stepdaughter’s seizures, a condition she’s had for years and is exacerbated by heat and excitement.

“It was a nightmare,” Outlaw said. “I got some studying done, but it was very difficult. It was the worst educational experience I ever had.”

Soon after classes restarted, FEMA advised that they could offer some assistance – $17,000 – but nowhere near the $40,000-plus needed to make the house livable. “We were not in a flood zone, so we did not have flood insurance… It was either walk away with nothing or rebuild.”

Meantime, he got another piece of bad news. With all of his time spoken for, extra math tutoring was no longer an option. And with all the scrambling to meet basic needs for him and his family, his cell phone study time was proving insufficient. He had a C- in math. Like his peace of mind, his 4.0 GPA was on the verge of extinction.

“That was actually the worst part of the whole experience,” he said.

‘Dealing with the cumulative effects that come with these storms’

Outlaw and Jenkins are exactly whom the politicians are talking at when they promote the American Dream. Outlaw accepted dropping out as a mistake. Rather than grow bitter, he earned a GED and enrolled in community college to better himself and his family. Jenkins got laid off after two decades of accounting work. She enrolled in community college for a degree that would allow her to command the salary her experience earned.

Neither are looking to get rich quick. Neither are afraid of hard work. But here they both stood at the precipice of leaving college early because massive flooding in their community forced them to choose between daily basic needs and the promise of a more comfortable tomorrow.

And they’re not alone. Thousands of North Carolina’s community college students faced this decision in the wake of three massive storms hitting the Carolina Coast within the past three years.

A phlebotomy student and single parent at Carteret Community College who lost three weeks’ wages due to damage caused by Hurricane Florence. A business administration student at Bladen Community College who was rescued by helicopter from her home and lost everything. An associate of arts student at Coastal Carolina Community College, whose home was declared uninhabitable and lived with her kids in a tent under her carport.

These are just a few of the stories from community college students who faced financial distress after Hurricane Florence threatened their ability to continue classes. In these three cases, and many others, state emergency grants allowed them to stay in school by paying for rent, car payments and courses. For thousands others, however, studies were interrupted.

Across 19 community colleges along the state’s eastern coast, more than 12,000 students stopped out after Florence. North Carolina’s community colleges are funded based on the previous year’s enrollment. Data compiled by the state’s community college system showed that, added up, all of the lost full-time, part-time and certificate students added up to the equivalent of nearly 1,500 full-time students.

Now, one year later, some students have returned and graduated. Others are re-enrolled, walking a longer road toward graduation than anticipated. And for some, graduation is a dream deferred.

In North Carolina, the mission of the Community College System includes “[opening] the door to high-quality, accessible educational opportunities that minimize barriers to post-secondary education…”

Traditionally, for many who enroll in community colleges, those barriers looked like struggling to balance ongoing paid employment and family obligations with time spent in classes, studying, or training.

That’s changed the past three years. As storms pop up in the Atlantic regularly during hurricane season, some wonder if the change could be the new normal.

“There are many in our communities and throughout North Carolina who are dreading what could await them this year,” said Toddi Steelman, dean of Duke’s Nicholas School of Environment. “You can see it in people’s faces … We are dealing with the cumulative effects that come with these storms. And they have enormous effects on our communities and our emergency responders. The repeated flooding, the repeated losses and the repeated trauma, all deplete our collective resiliency.”

Resiliency is a prerequisite for many community college students. Many are tasked with overcoming obstacles even before submitting college applications.

While some students attend community college to save money or supplement their career portfolio with certificates, many are searching for life-changing opportunity.

More and more, however, that opportunity means taking on the risk of extreme weather. How you fare against those odds is the difference between success and failure. The gamble is a scary one for community college students in these parts, considering the demographics of those in most rural Eastern North Carolina communities, not to mention the profile of the average community college student.

“Disasters are equal in the fact that they do impact everyone, but they also discriminate,” Steelman said. “We know that those who are most vulnerable — the poor, the disenfranchised, the disabled, and the elderly — suffer the greatest in these events. And they continue to suffer long after those of us with more resources have been able to recover.”

Community college students tend to fit this idea of vulnerable. It doesn’t take an unprecedented natural disaster like Hurricane Matthew or Hurricane Florence to push them out of college. A broken-down car, changed work hours, new financial needs or a family member’s illness — roadblocks large and small force students statewide to stop enrolling for a semester or longer.

But for thousands of students across the region, Florence threatened to be a tipping point.

Stop-gap solutions

North Carolina is getting more accustomed to and experienced at handling storms. In the wake of Florence, the legislature allocated $5 million in emergency funds for the state’s community college system to divvy up among 21 impacted colleges. The money went to help students like those described above.

But for some community college students, the problems feel too big and the solutions too small. A sense of loneliness in the face of tremendous life upheaval pervades this group of diploma seekers, who might not come out and ask for help.

“That’s the fear, I guess,” Carteret Community College President John Hauser said. “Do they know that the money is there? Will they come out and ask for help?”

While environmental experts and politicians work out longer-term solutions and the state aids with stop-gap emergency funds, some community colleges are taking a proactive approach to preventing stop outs.

At Pamlico Community College, for instance, the college is taking a personal approach. Pamlico County is located on the Eastern Seaboard, bordered by the Pamlico River to the north, Neuse River to the south and the Atlantic on the east. The school is the smallest of North Carolina’s 58 community college, and flooding from recent storms have hit it hard – both by way of damage to facilities and lost enrollment.

Without the resources to divert to advisors and mentors, president Jim Ross has set up a team approach to ensuring students stay enrolled. These range from personal calls to students no longer signing up for classes to individually reaching out to students on the “purge” list, a ledger of students who are signed up but have not paid for the upcoming semester and are in danger of being unenrolled.

“We proceeded with going above and beyond the norm and lending a helping hand to say, ‘We care about you, let us help you, let’s do this together,’” Ross said. “It just shows you the team effort and caring about people as people, versus just as numbers.”

A May graduation

For Outlaw and Jenkins, help arrived in the form of non-profit aid.

Jenkins didn’t struggle with her college decision long. Once her kids were back in school and the family in their rental home, she got the little bit of breathing room she needed.

“It is difficult to keep your mind on work, to keep up with all the work,” she said last year. “I stay motivated knowing that I will graduate in May – I stay focused on that. … My plans are to clean up my property, graduate, keep working … and then hopefully I will be able to build my house back in a couple of years.”

In May, she crossed the first item off that to-do list. With help from family and friends, she replaced her kids’ school clothes and supplies, helped them finish out their school years and spent the little time she had left after work and classes on studying.

She graduated the same semester as Outlaw. She even got to walk across the stage.

“I didn’t think I was going to graduate,” she said. “But I did. I can understand not wanting to keep going, but we’re not supposed to give up. We’re supposed to keep striving.”

But her mind is plagued with questions. What will they do with their property, which has been in her family for almost 100 years and now sits vacant? And how long until they own a home of their own again?

“Every day it gets better,” Jenkins said. “It’s hard for the kids. Because they thought this was their forever home. My children have never moved into another home before. This was their one and only home. So seeing their house torn down and understanding you know, that we are not going back to our old house. We are adjusting to what works, what doesn’t work … There are some days that you want to cry, some days that you smile.”

Outlaw managed to struggle through his final semester at Sprunt, mostly using his cell phone to study and complete assignments. When he needed his laptop, he found a McDonald’s to borrow the WiFi and got his work done. But amid all the cash he was bleeding, there was another price to be paid by Outlaw: He got a C in math and missed out on the 4.0 goal.

“The president there at the time, he was such a nice man,” Outlaw said. “He told me when I was ready, I could retake that math class and he would pay for it out of his own pocket.”

But the 4.0 goal was so far down the list of priorities. His family needed a home, and he needed to move on to other life goals. He scraped by, largely on the back of the hard work he put in the first three semesters, and earned enough credits to graduate last May.

He couldn’t walk to get his diploma, though. He was busy figuring out what to do with his damaged property.

He found a small house in Goldsboro and now commutes 45 minutes to Kinston for his welding job. He’s paying a second mortgage though, as payment is still due on the house he has now given up rebuilding. FEMA has yet to determine if they will buy out the property, but Outlaw has settled on the reality that his dream home will never be a home again.

Extensive mold still plagues that dream home, and he recently discovered termite damage that the previous owners may have covered up.

He’s in his late 40s now, and money remains tight. Still, he talks about gratitude for shelter over his head and food to eat. He leans on faith and, despite money going out just about as quickly as it comes in, he prays for others. If this experience has taught him anything, it’s that he needs to keep working hard to be prepared for the future.

“My faith was rocked a little bit, but I never lost it,” Outlaw said. “You can’t help but to ask, ‘Why? Why did this happen to me? Why to my family?’ But, I believe God has a plan.”

He loves his welding job, but like Jenkins, he’s left with may questions. He wonders how long his body can physically withstand the rigors of welding. He wonders what to do with his moldy, tattered home. He wonders whether he’s gained any ground by getting his degree and a better-paying job only to take on a second mortgage. He wonders how long ends will continue to meet.

Catalyst for lasting change

Last Spring, Jenkins and Outlaw sat with a group of North Carolina philanthropists that focuses on postsecondary attainment. For Jenkins and Outlaw, it led to financial freedom.

“We told our stories there,” Outlaw said. “It was moving. There were people crying. It was very emotional.”

One of the philanthropists offered both students full scholarships if they chose to finish their bachelor’s degrees. Both have enrolled in nearby University of Mount Olive, pursuing degrees in business administration. It’s the kind of degree that represents hope for a long-lasting, well-paying desk job for Outlaw. For Jenkins, the bachelor degree represents the possibility of reinvention.

She has been substitute teaching, but once she graduates from Mount Olive she hopes to teach full-time. And her next goal is a master’s degree, because she hopes one day to teach at the college level.

“There were days when I thought, do I need to go ahead and fix all this and worry about education later – but it’s worked out,” Jenkins said. “It’s worked itself out. There’s some days I still don’t know how it’s going to work out, but it does somehow or another.”

The scholarship doesn’t help with food. It doesn’t help with getting out from under the cost of lost homes. Those burdens remain on Jenkins and Outlaw, but both have grown accustom to struggle. And if they can hold on and graduate, both of their eyes beam with the incredible lessons they hope they’ll have passed onto their kids.

“I really wasn’t ready to enroll this year, because we’re still dealing with all of this,” Outlaw said, motioning around the wreckage inside his flooded home. “But I didn’t want to complain. It’s such an honor and such a wonderful opportunity. I just don’t want to let The Belk Foundation down, or James Sprunt. Because I respect a lot of people there.”

Outlaw has held onto that C- in his final math class at Sprunt for longer than any other grade he remembers receiving. He sorely wishes he could have taken then-interim president Ken Boham up on his offer to retake the class. It stands out, alongside the house, as the blemish his hard work hasn’t been able to fix since Florence.

But he’s hoping graduating from university will offer opportunities that will help him forget about that shortcoming. He’s not harboring dreams of becoming rich, but he hopes that a well-paying job after graduation means comfort – and that he can start to rebuild his life post-Florence.

“It’s not over yet,” he said. “I still relive it. It’s still on our minds.”

When the day comes that Florence is finally nothing more than a memory — if he’s still up for it, that math class at Sprunt will be waiting.

“The offer still stands,” Boham said.

This is the third piece in a series on challenges facing community college students titled: An Extra Hill to Climb. This installment was co-published by MSN.com, which is running it as part of their Poverty Next Door spotlight. Our series is a partnership between EdNC.org and Spotlight on Poverty and Opportunity, which is a non-partisan initiative that gathers diverse perspectives to tell compelling stories illustrating the economic hardship confronting millions of Americans and to lift up genuine solutions. EdNC.org and Spotlight partnered to illustrate the challenges facing many community college students through stories from North Carolina and data illustrating the broader challenges in the United States.