New buildings spanning the horizon, futuristic bridges, a massive new rail project, and even a brand new “city,” dubbed the Future Science City, built to attract new high-tech industry. These are but a few of the examples of strategic investment one sees on a trip between Beijing’s city center and the Huairou District along the G45 Daguang Expressway. It’s a view that leaves one with the clear appreciation that China is not messing around.

This was my overwhelming impression after being in the country for 10 days as part of the U.S. Delegation for the Beijing Youth Science Creation Competition this past March. According to the Beijing Municipal Commission of Development and Reform, over 235 billion yuan ($35 billion) has been approved for over 300 major construction projects in that city alone. Projects are focused on technology, infrastructure, and much-needed improvements to the city’s environment. Add to this the almost ubiquitous ads for Huawei’s 5G technology, banners celebrating China being the first to land a spacecraft on the far side of the moon, and the city’s high-end shopping district that would rival anything seen in the west, and you clearly see that China is playing the long game and playing it quite well.

Their “Made in China 2025” plan to invest vast sums into technology and innovation was on display for all to see, as was the implied goal to leapfrog the United States in terms of being the world’s leader in computing, artificial intelligence, and robotics. This point brings me back to my involvement in the international science competition and my specific interest as an educator on the U.S. Delegation. Specifically, what role is education playing in China’s aspiration to dominate the high-tech sector?

Education as a catalyst for growth

The ability of a country to grow its capacity for innovation rests in large part with its education system, and investment in education has long been seen as a way to foster such innovation. For example, the U.S. Congress responded to Sputnik 50 years ago with the National Defense Education Act, pumping huge sums of money into education at all levels, with an explicit focus on scientific, math, and technical education.

Is there evidence that China is doing the same as a way to build the intellectual capacity of future generations? It was hard not to appreciate the country’s deep appreciation for education, including family pressure to do well academically and the respect the country has for teachers, but how is it capitalizing on this cultural priority as it tries to play a more dominant role on the world’s stage?

To answer this question, I spent a lot of time having intentional conversations with teachers, students, and coordinators of this competition, as well as local university students who were acting as our hosts. Granted, most of these conversations were from what could arguably be identified as China’s top schools, so it was not a representative sample of the typical school (to be fair, all of the students from the U.S. were from the North Carolina School of Science and Mathematics, a prestigious public boarding school for academically talented students).

I also listened to lectures by some of China’s leading academics, school leaders, and government officials as they spoke to how to cultivate international innovation, with an obviously Asian perspective to the global marketplace. Through these lectures and conversations, I was better able to appreciate the country’s approach to education and its plan to boost scientific and technological innovation.

For starters, China has the largest education system in the world. And unlike the myth that we often hear in the U.S, they do have a compulsory education law for all Chinese children, albeit for just nine mandatory years. It was also evident that educators in China are held in high regard based on the respect given to teachers during the competition and accompanying events. I learned in my conversations that teachers undergo rigorous preparation, with considerable time spent doing classrooms observations and working directly with more experienced teachers, both before and after they enter the profession. Peer collaboration apparently plays a much higher priority in Chinese schools. Every teacher I interviewed made it clear that they were expected to work together with peers on lesson plans and to help each other improve.

Nevertheless, several of the people I interviewed were also willing to share what they saw as problems with their education system. They candidly acknowledged that wealthier families had much greater access to high-quality education options than lower income families, especially those from rural areas of the country. Moreover, wealthier families can evidently pay special fees in order to access better primary and secondary schools outside of their local area and pay for expensive tutors to prepare their children for the Gao Kao (China’s version of high-stakes testing, only on steroids, given that it is offered only one day each year and is the single biggest factor for a student’s pathway into Chinese colleges and universities). In fact, the second most common criticism I heard was related to what is viewed as an unhealthy emphasis on memorization and preparing for this high-stakes test.

It should be noted that the Chinese Ministry of Education is aware of the wealth gap and is apparently working to reallocate funds to provide better support to low-income communities. The country is also acknowledging that a significant equity gap exists between urban areas with those in rural parts of the country. One college student I spoke with had experience as a “contract teacher” in a rural part of the country and indicated that he saw first-hand how the lack of funding and training was having a detrimental effect on the quality of teaching in rural China.

Despite these problems, however, my new Chinese friends were also quick to point out that they, along with Hong Kong and Macau, were consistently in the top 10 of PISA scores for math and science (the PISA is the Programme for International Student Assessment and, unless you have been living under a rock, you are probably aware that the U.S. is nowhere near the top 10). So, why is this? What are the Chinese doing in their schools that is so different from those here in the U.S.?

Lessons learned from China

To really dig into that answer would have required me to have spent much more time in schools in order to expand my sample size beyond what were clearly some of the top schools, students, and educators the country had to offer. That said, I was able to use the experience to make some observations that hint at some clues to their success.

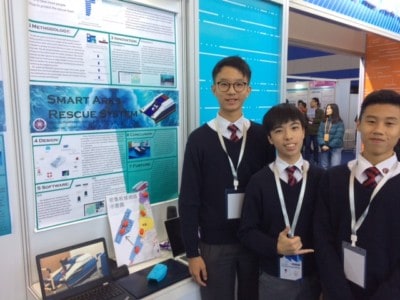

One observation was how the Chinese have somewhat perfected a standardized model of education — one that we often criticize in the U.S. for its emphasis on teacher-centered compliance and control. Watching various local school groups tour the competition floor, for example, reminded me of the opening parade at the Olympics. The pupils from each visiting school were all dressed alike in their unique school uniforms and were respectfully engaged in the competition, making observations, taking notes, and questioning presenters — especially presenters from other countries. That’s not to say that they were behaving like passive robots — kids will be kids, after all. But it was clear that they had a purpose in being at the competition and the level of respect and obedience they gave their teachers was remarkable.

Another eye-opening statistic that I was admittedly ignorant of before this trip was China’s standing in the world in terms of higher education. As was pointed out in one of the lectures I sat in on, China now has the second highest number of universities listed in the Academic Ranking of World Universities (second only to the United States). The speaker proudly stated that no longer did they gauge success based on the number of Chinese students attending U.S. universities, but how many U.S. students were now attending Chinese universities. I also heard examples of policies the government is taking to reduce the emphasis on high-stakes testing and to update its curriculum from primary to postsecondary school to better match skills required in a global, innovative economy.

So, does all this mean that we should be learning from the Chinese in terms of how to reinvent our own education system? Yes and no. Having a clear-eyed priority on developing and maintaining (more of the latter in our case) a dominant role in the 4th Industrial Revolution has to be a national priority, and it must also include renewed education priorities. The U.S. would do well to look to China for examples that could inform such work.

The country’s cultural value for education in general, and teachers in particular, is another area we could learn from, although I’m skeptical that we can muster the political and societal will to make such large-scale changes to public perception in this regard. And certainly anything that the U.S. can do to reduce its own national curriculum of test-prep insanity would be a good step in the right direction.

A key point of difference

The one area where I would suggest that we not try to replicate China’s model, however, is in their approach to standardization, compliance, and control. As mentioned above, I believe their societal appreciation for this traditional approach to teaching (and to a large extent, parenting) makes it quite effective for their culture, but not so much in the U.S.

In fact, I believe we are fighting a losing battle to pretend that we can compete with the likes of China, Indonesia, Korea, and Singapore in terms of this traditional approach to education. Where the U.S. can excel, I believe, is by moving away from this “industrial” model and tapping into our value of individualization, creativity, and innovation, where each student is allowed the opportunity to collaborate with her or his peers to solve messy problems that have real-world context.

This is where cross-curricular projects that involve deep thinking, learning from mistakes, and producing a public product can create a passion for lifelong learning and will bode well for our country’s future — ones akin to what our four American students presented at the competition, as well as those like my own students routinely did at Tri-County Early College. This forward-thinking mindset should influence the United States as it has more conversations about how we should rethink our own obsession with high stakes testing.

Any country that is going to take a proactive approach to leading in a rapidly changing world has to take a serious look at its educational systems and align them to maximize its cultural and intellectual capacity. My time in China left an unmistakable impression that this is exactly what China is doing as it makes a long-term play to dominate in technology, artificial intelligence, and computing.

The U.S. would be well-served to do the same — not by copying what China has done, but by breaking away from a status quo that’s not working and investing in a shift to an education model that’s inherently more conducive to our own country’s values of innovation and entrepreneurship. Doing so, I believe, would be evidence that the U.S. is playing the long game equally as well as the Chinese. It would mean that we have a bold new vision of education, with a sense of urgency that aligns with our country’s future prosperity. Do we have the will to do so? Time will tell.

In March 2019, Ben Owens served as a delegate with the finalists of the North Carolina International Science Challenge. The NCISC is an annual competition managed by the NC Science, Mathematics, and Technology Education Center where high school students from NC submit original independent research and maker projects in the hopes of presenting at an international competition. Visit http://www.