North Carolina’s public preschool program, NC Pre-K, ranked in the middle of similar programs throughout the country on such measures as spending, access, and quality in the National Institute for Early Education’s (NIEER) State of Preschool 2019 report.

And Steven Barnett, NIEER’s senior co-director, said the state should rethink its pre-K structure to survive the economic impacts of COVID-19.

“There are some key systemic issues for North Carolina that probably apply to other states,” Barnett said. He pointed to the fact that NC Pre-K, which serves about a quarter of the state’s 4-year olds based on family income and other “at-risk” factors, funds one child at a time across a variety of private and public settings. Some states, he said, fund entire classrooms at a time.

“With half of child care programs closing and uncertain whether they’ll be able to reopen and having severe financial problems, if you have only one or two kids in your program that’s serving state pre-K, you could have serious capacity problems when you try to reopen,” he said during a teleconference Monday.

Thinking about how to fund NC Pre-K as it works with the private child care system, as well as figuring out how to retain high-quality teachers with less funding, will be crucial for NC Pre-K “to avoid disaster in the coming year,” he said.

A look at the numbers

NC Pre-K, created in 2001 and originally called More at Four, has been studied by the Frank Porter Graham Institute since its inception. Studies have found positive school readiness and social and academic outcomes in the early elementary years for children who participate in the program.

In almost the same place as in last year’s NIEER rankings, the state’s pre-K program was 21st in state spending, ninth in total spending, and 27th in access using data from 2018-19, when compared with the other 49 states and Washington, D.C.

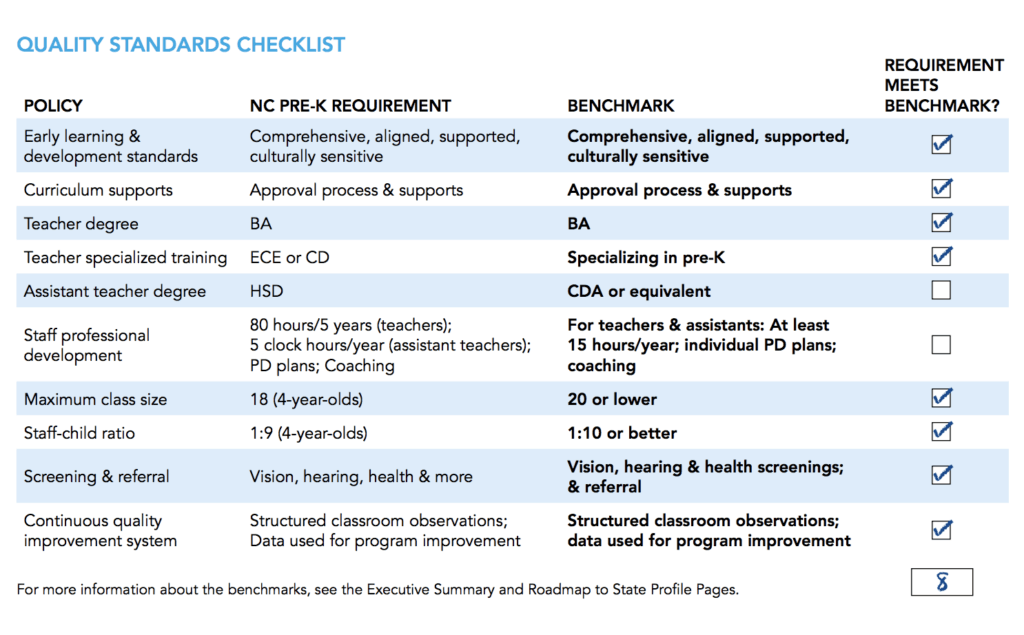

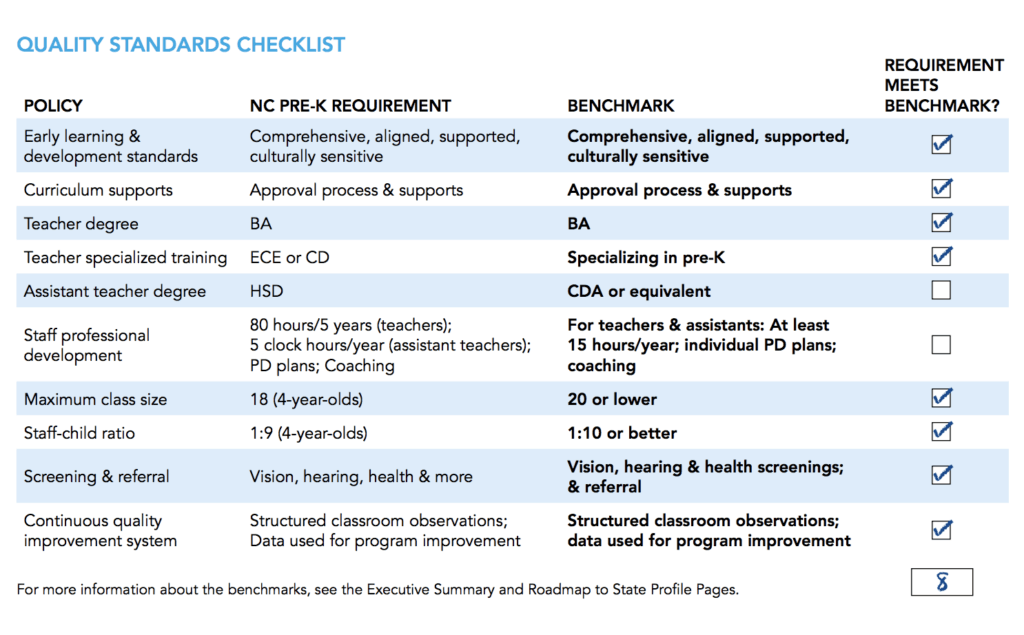

The program continued to meet eight of the report’s 10 quality benchmarks — research-backed markers of program effectiveness. It showed up in one “Top 10” list — on total spending per enrolled child: $9,162. That funding comes from a variety of federal, state, and local sources.

When it came to just state dollars, North Carolina spent $1.25 million more than it did in 2017-18. The program increased enrollment by 1,124 children (for a total of 29,509 children enrolled). That brought access up a percentage point from last year (to 24%) and state spending per child slightly down to $5,450, from $5,428.

About 60% of each NC Pre-K slot is covered by the state through budget allotments. The rest is paid for with a mix of federal and local funds. The General Assembly pledged to spend an additional $9 million on the program each year from 2017-18 to 2020-21 to enroll more children.

- NC Pre-K served 29,509 4-year-olds in 2019, enrolling 1,124 more than in 2018.

- The state increased its spending by $1.25 million in 2019, but per-child state spending dropped slightly, to $5,450.

- When adding in other federal and local funding sources, NC Pre-K’s per-child spending was at $9,162.

- The state ranked 21st in state spending, ninth in total spending, and 27th in access for 4-year-olds in 2019.

What does it take to expand access?

NC Pre-K funding, as Barnett mentioned, pays for slots in private child care centers and public elementary schools. The provider receiving the funding must meet certain requirements, such as staff education levels and teacher ratios.

Reaching more children takes more funding, but the picture is more complicated than that, according to a separate 2018 NIEER report that studied reasons why some counties were turning down state money to expand. The report found that the funds given to each provider do not cover costs for more physical space, transportation for children who need it, or finding and keeping high-quality teachers:

“The overriding, fundamental barrier to expanding NC Pre-K is that revenues and other resources available to NC Pre-K providers are too often inadequate to cover the costs of expansion. Exacerbating that fundamental barrier are:

– Rising operating costs, including costs to recruit and retain qualified teachers, expand facilities and provide transportation.

– Stagnant state reimbursement rates since 2012 that fail to cover NC Pre-K costs.”

Advice for states as COVID-19 brings funding cuts

This year’s report ranked states on their preschool programs, as it has since 2002, but it also provided recommendations to the states to maintain quality pre-K programs in the coming years as budget cuts come from the COVID-19 pandemic.

“The COVID-19 pandemic and the current and, I think, looming economic crisis pose considerable threats to state-funded pre-K,” Barnett said. “In most states, pre-K is discretionary, but it needs to grow and improve, not just hold on.”

Barnett said 2008’s Great Recession provided lessons on how an economic downturn affects spending and quality levels for pre-K programs.

“We know in the last recession, enrollment, spending, and quality standards were cut, and that spending impacts continued well after the economic recovery was underway,” he said. “In fact, the impact of those cuts continues.”

Since most pre-K programs target low-income children, Barnett said, lower program quality can widen gaps in opportunity and achievement for children.

“As pre-K programs tend to serve lower and middle-income families, that means that cuts to pre-K like this, rollbacks in quality, exacerbate educational inequality.”

The report provides the following recommendations to mitigate these effects:

1. The federal government should provide states with dedicated funding to stabilize and expand preschool programs while maintaining or enhancing enrollment and quality.

2. Improve coordination of Head Start and state pre-K policy to better serve preschoolers living in poverty.

3. Make funds available to state pre-K programs for developing rapid response plans to the current crisis and long-term plans for its lasting consequences.

4. State pre-K programs must rapidly develop new policies to provide emergency services and educate young children remotely for the remainder of this school year and for the coming summer and fall.

5. Each state should develop long-term plans that incorporate a definitive timeline and realistic funding estimates for a high-quality pre-K program that provides access to all children.

Barnett said the economic crisis will mean more demand for pre-K programs that are means-tested, like NC Pre-K, in the coming years. That means more state planning and dedicated funding are necessary, he said.

“We acknowledge that’s going to be difficult in the current circumstances, but it needs to be done,” he said. “We need to think about the long term as well as the short term.”