As a new school year dawns, North Carolina’s charter sector is poised for robust, continued enrollment growth. Yet experts point to increasingly high hurdles for new charter schools, with facility acquisition and increased competition for students topping the list. Established, rather than new, charter schools are the primary drivers of enrollment growth now, as obstacles to opening and other K-12 changes reshape the sector.

“The challenges of getting open are vast,” said Ashley Baquero, the executive director at the state’s Office of Charter Schools (OCS). She is seeing more delays from schools in the charter pipeline, as they struggle to find and finance facilities and hit enrollment targets.

Meanwhile, established charter schools with facilities, funding, and reputational capital continue to expand.

“The data has shown that the schools that have been around a little bit longer tend to be the ones that are growing — where a lot of the new enrollments are coming in,” said Bruce Friend, chair of the state’s Charter Schools Review Board (CSRB).

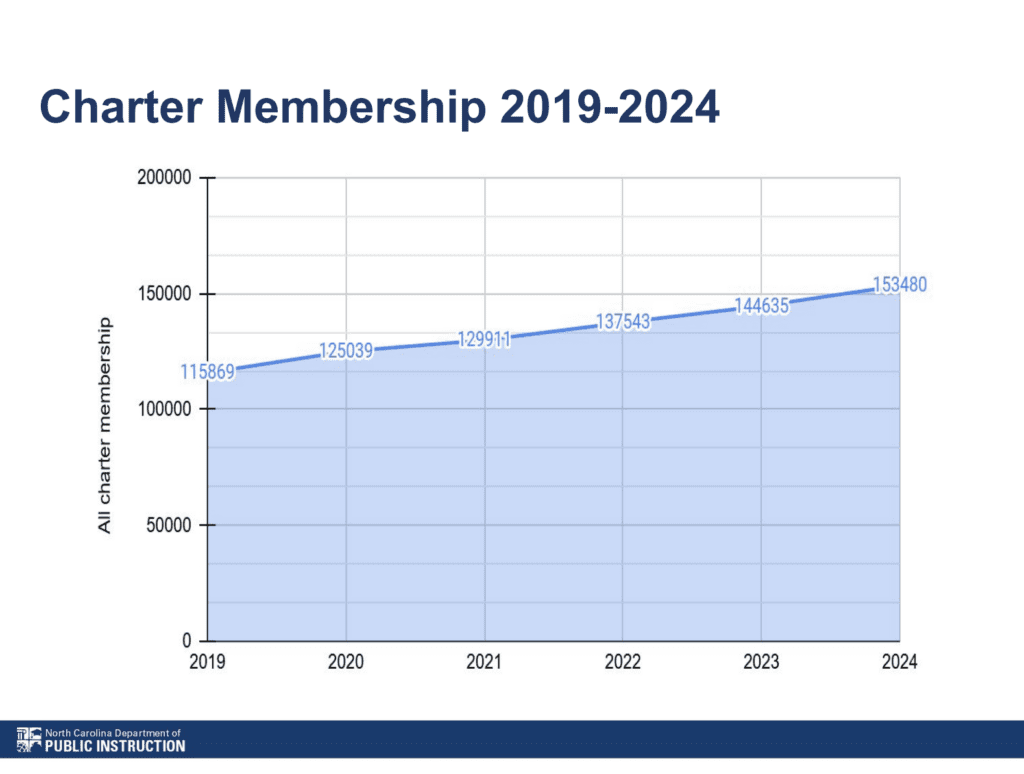

During the 2024-25 school year, state charter enrollment increased to 153,480 students, according to the new annual charter schools report from OCS. This figure represents a 6.1% annual enrollment uptick and an overall increase of 8,845 students since 2023-24.

Charter demand continues to outpace supply: 77% of state charter schools reported waitlists last year, totaling 74,287 students.

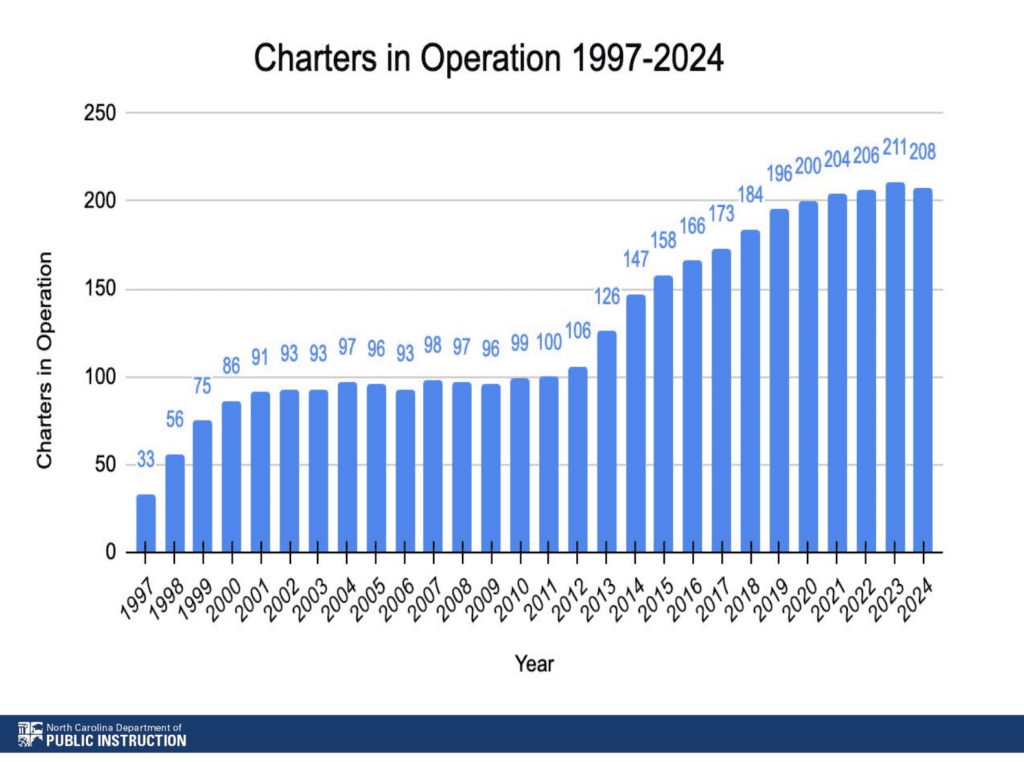

Somewhat paradoxically, however, the number of charter schools in 2024-25 declined for the first time in 14 years, dropping to 208 schools from 211 the year before. This is the first school downturn since state lawmakers removed the cap on charter school growth in 2011.

Only two new charter schools opened last year: ALA Monroe and Riverside Leadership Academy. Together, they accounted for 6.5% of the total annual enrollment increase, based on final Average Daily Membership (ADM) figures.

Factors influencing the drop in schools

The 2024-25 numbers communicate dual — and dueling — messages. They challenge the notion that an increase in schools is somehow inexorable for the state’s thriving charter movement. Yet they also reinforce what Friend described as “tremendous growth and demand for charter schools.”

A “combination” of factors impacted the drop in schools, said Friend. Those factors include school closures directed by the CSRB as well as schools that relinquished their charters and closed voluntarily.

Nationally, growth in the number of charter schools is impacted by politics, demographic changes, the size of the charter sector, and to some degree, private school choice expansion, said Todd Ziebarth, the senior vice president for state advocacy and support at the National Alliance for Public Charter Schools. “That continues to vary from place to place.”

But a persistent pattern, across the nation, is this: Charter enrollment continues to grow, with more families embracing these public schools of choice.

Enrollment growth and established schools

In North Carolina, “it’s becoming increasingly difficult for smaller schools who want to grow and for new applicants who want to get started,” said Friend. Instead, growth is occurring predominantly at “mid-size to larger” schools.

Existing charter schools can expand their facilities on their current property or even serve new grade levels at a sub-campus property down the road, Baquero said.

State law, passed in 2023, removed enrollment growth caps for charter schools in their second year of operation, provided they are not low performing. Charter schools may also add a grade level without CSRB approval — if they are financially compliant, in at least their third year, and are not continually low performing.

In addition, charter schools can seek CSRB approval to supplement brick-and-mortar offerings with remote academies, an option made possible by a 2023 provision in the state budget.

As an example of current enrollment trends, Friend cited Pine Springs Preparatory Academy, where he serves as superintendent.

Located in Holly Springs, Pine Springs launched in 2017 with around 460 students. Now, the school has grown to serve 1,275 K-8 students — but just at its brick-and-mortar location. Pine Springs also operates blended (grades 4-10) and fully virtual (K-12) remote charter academies.

Both learning environments “can fall under that umbrella that we define as a remote academy,” Friend said.

Last year, the school’s blended model served just under 100 students. The fully virtual academy, which operates statewide, enrolled 2,200 students, bringing Pine Springs’ total enrollment to around 3,575 students. The school, Friend said, is now larger than 40 North Carolina school districts.

Pine Springs also plans to launch a new upper school in 2026.

What about the charter pipeline? Aspiring charter boards must navigate a fraught facility process, and a reconfigured, highly competitive K-12 landscape.

In North Carolina, charter schools do not receive capital funds from the state for their facilities. Securing sufficient monies to purchase a building outright can thus be prohibitive for start-up charter boards, unless, as Baquero noted, they “are supported by an EMO [education management organization] or some type of private funding.”

Parental expectations have also changed, said Lindalyn Kakadelis, a member of the CSRB. The state’s early charter schools often launched in “very small” and unconventional spaces, such as business offices. Now, parents “want a large school,” she said.

Upping the ante: In more populous parts of the state, families can choose from a menu of K-12 models including public district, magnet, and charter schools; private and home schools; and a panoply of virtual options. Parental risk tolerance has shifted accordingly.

“It’s just really competitive right now,” Baquero said. Parents are better informed and are “less likely to say, ‘Ok, I’m going to try this’” with an untested new school.

A snapshot of North Carolina’s charter sector

Even as charter enrollment shifts, it is growing more rapidly than other school models. With its 6.1% annual enrollment increase, charter schooling represents the fastest growing segment of K-12 enrollment in North Carolina right now.

Homeschool enrollment, at an estimated 165,243 students, was slightly higher than charter schooling last year, but grew at a slower rate, 4.8%, according to new state data. State figures show private schooling increased by 3.4% in 2024-25, to 135,738 students.

State charter enrollment has diversified as it has grown, the annual reported noted. Compared to district schools, charters served higher percentages of Black/African American, Asian, and White students last year, along with students of two or more races. District schools served greater percentages of Hispanic and economically disadvantaged students as well as students with disabilities.

Yet, Hispanic charter enrollment has increased considerably since 2010, rising from 5.8% to 14.8% in 2024. White charter enrollment declined by around 16% during that timeframe.

Weighted lotteries have helped charter schools diversify their student base. More than 70 charters have received approval to weight their lotteries, enabling them to prioritize admission for educationally disadvantaged students.

“The data tells a story of a charter school sector that has fundamentally changed its demographic composition over 14 years, becoming significantly more diverse and reflective of broader demographic changes in the student population,” OCS summed up in the annual report.

National charter comparisons

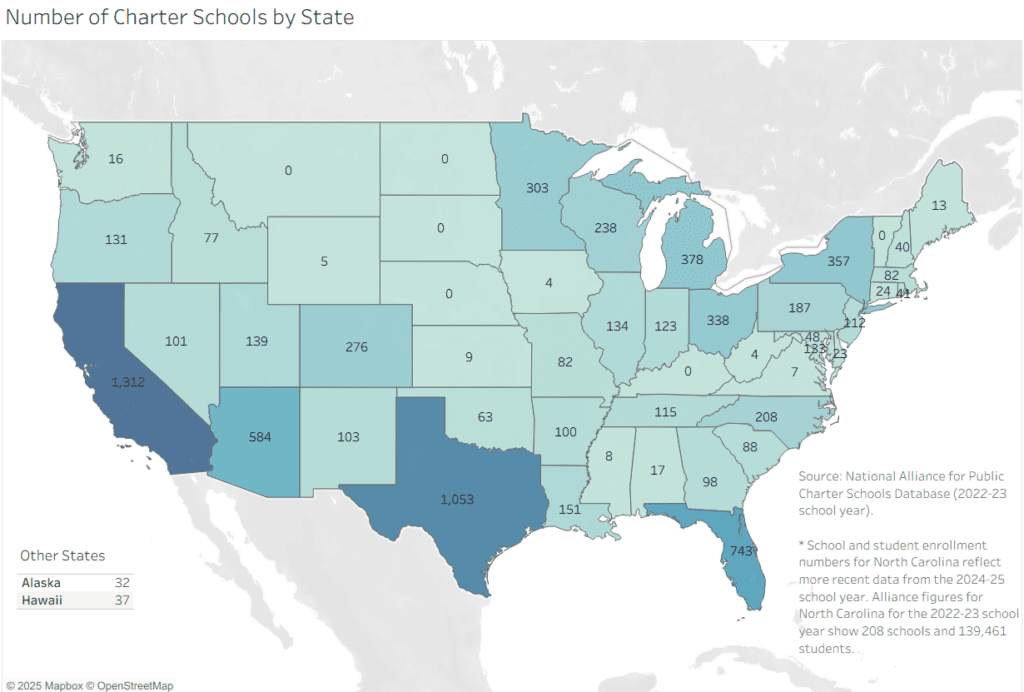

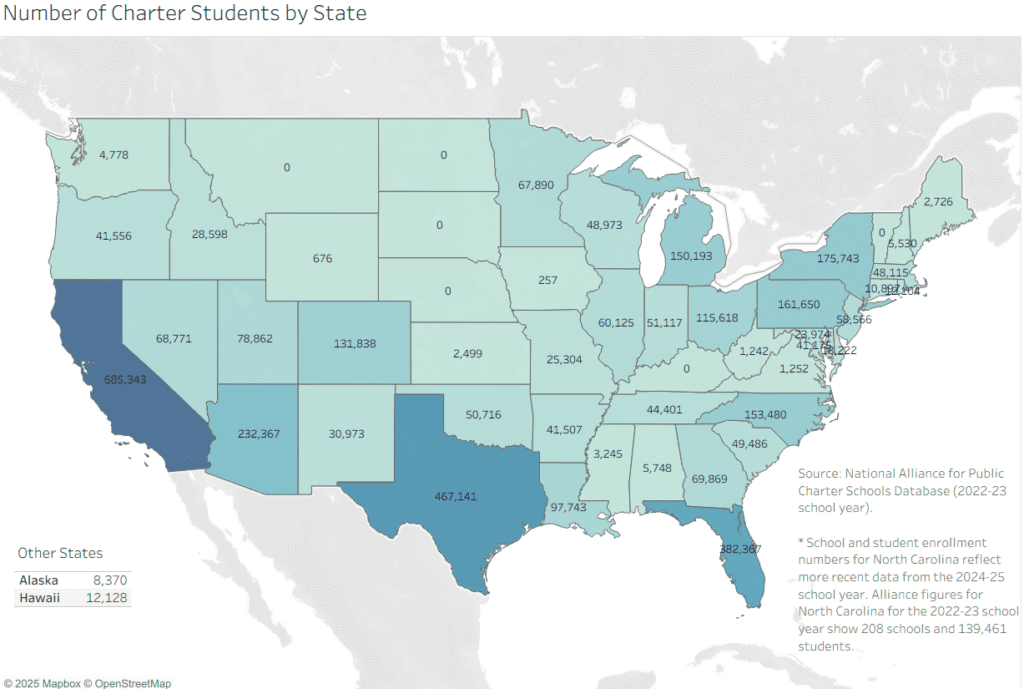

How does North Carolina stack up to other states? The state accounts for nearly 2.6% of the country’s charter schools and 3.7% of its charter students, according to 2022-23 numbers from the National Alliance for Public Charter Schools database.

California leads the country in charter schools, followed by Texas and Florida. Ten states — Arizona, California, Colorado, Florida, Michigan, Minnesota, New York, Ohio, Texas, and Wisconsin — have more charter schools than North Carolina.

Seven states — Arizona, California, Florida, Michigan, New York, Pennsylvania, and Texas — have more charter students, based on 2022-23 data.

Even as the nation’s charter sector continues to expand, some states still do not have charter laws.

North Dakota passed its charter law this year, Ziebarth said, but Vermont, Nebraska, and South Dakota have not passed laws permitting charter schools.

Ziebarth is “hopeful that South Dakota will do so next year, and we’ll be at 48 states,” he said. Iowa and Wyoming have “overhauled their laws, and we’re seeing growth in schools and students in those places,” he added.

Kentucky and Montana have inactive laws that are being contested legally. In West Virginia, the state supreme court allowed the charter program to be implemented amid an ongoing court challenge, Ziebarth said.

In total, 3.76 million students attended 8,150 charter schools nationwide in 2022-23, according to Alliance data.

Regional disparities in access

Despite steady enrollment growth, North Carolina’s charter sector reflects substantial regional disparities in access. Last year, for instance, 101 charter schools — nearly half the state’s total — were concentrated in these six counties, according to the annual charter report:

- Buncombe: 7 schools

- Durham: 14 schools

- Guilford: 13 schools

- Mecklenburg: 34 schools

- New Hanover: 7 schools

- Wake: 26 schools

Is the sector approaching saturation in some areas?

It’s a “real possibility” and a “logical question,” said Friend — and one the CSRB considers for charter applicants, closely evaluating their proposed location and proximal school choice options.

The answer to the saturation question will ultimately be decided in the K-12 marketplace, he said. “You know who knows the answer to that? The parents: Are they going to choose?”

Kakadelis believes the state may be “hitting a saturation point” in some counties. However, when schools fail to meet enrollment goals, she said she also questions the efficacy of their marketing efforts.

“If you have a good product, you’ll get students,” she said. “There’s always room for good schools.”

Meanwhile, 37 North Carolina counties do not have even one brick-and-mortar charter school.

Is there a need to catalyze growth in rural counties? Some areas may not have sufficient demand or students, Kakadelis said, or lack the local expertise to launch a school.

Still, she believes charter authorizers should be mindful about broadening access when they see applications from underserved areas.

“As the Charter Schools Review Board, we need to seriously consider those counties when an application bubbles up,” she said.

New schools and remote academies

Seven new charter schools are opening this fall, having received final approval from the CSRB in June. This is a surprisingly large cohort, given current obstacles. Yet most of the schools are quite small and will have a very modest impact on overall charter enrollment this year.

Figures included in the OCS Ready to Open report on June 9 show new schools planned to enroll 1,257 students altogether. Numbers may fluctuate this summer, but just two schools had enrolled more than 150 students each by early June. Those schools are North Oak Academy (managed by EMO National Heritage Academies and enrolling 477 students) and Liberty Charter Academy (managed by new EMO American Traditional Academies and enrolling 248 students).

Established charters are also opening three new remote academies this fall, bringing the total to eight, according to Julie Whetzel of OCS:

- *Ascend Leadership Academy: Lee County

- *North East Carolina Preparatory School

- *Pine Springs Preparatory Academy

- Sandhills Theatre Arts Renaissance School (STARS Charter)

- *Telra Institute

- Tillery Charter Academy

- *Uwharrie Charter Academy

- Wilson Preparatory Academy

*These remote academies were also open during 2024-25.

Three additional charter schools plan to open remote academies in 2026-27: ArtSpace Charter, Carolina Charter Academy, and Longleaf School of the Arts.

Last year, remote charter academies served 2,194 students, Whetzel noted. Two standalone virtual charter schools — NC Cyber Academy and NC Virtual Academy — served an additional 5,791 students statewide.

In all, 7,985 charter students enrolled in remote charter academies or virtual charter schools in 2024-25, Whetzel indicated. This represents 5.2% of the state’s charter enrollment.

New legislation will make it easier for existing charters to launch remote academies. Senate Bill 254 – Charter School Changes was passed by state lawmakers in late June and vetoed by the governor in early July. On July 29, state lawmakers voted to override the governor’s veto.

The new legislation establishes an expedited approval process for some remote charter academies, among other things. Academies serving 250 or more students could request a separate charter from the CSRB and would forego a planning year.

Help with facilities

Charter advocates are working to help new schools surmount obstacles to opening. Nationwide, facility efforts focus on “funding, access to buildings, and financing options,” Ziebarth said.

“An increasing number of states, including even blue states like Colorado and Illinois and Massachusetts, provide charter schools a per-pupil facilities allotment,” he said. This is in addition to per-pupil operating dollars and represents “the most critical thing states can do.”

States are also promoting charter access to empty or underutilized facilities. “In Arkansas, for example, the state Department of Ed. compiles and maintains lists of available, underutilized district space, and then shares that with charter schools,” Ziebarth noted. Charters receive first right of refusal.

Other states, such as Utah, Colorado, and Idaho, have taken steps to help with facility financing through credit enhancement funds, seeking to “lower the bar in costs for charters,” Ziebarth said.

States making the most progress on facility funding — such as Colorado, Florida, and Utah — are creating a “menu of options,” he added.

Federal legislation could also help new schools. The Equitable Access to School Facilities Act would provide greater flexibility in the existing Charter Schools Facilities Program, Ziebarth said. Another bill the Alliance is pushing would create more flexibility in start-up funding through Charter Schools Program grants.

Facility funding represents “an area where North Carolina has a lot of work to do,” he said, although he expressed optimism that could change “over the next few years.”

“If North Carolina is able to enact some kind of funding mechanism for facilities, they’ll be able to tap into tens of millions of dollars at the federal level to help out charter facility costs,” he added.

Kakadelis said she expects the General Assembly to address charter start-up and facility funding, possibly as soon as the next legislative long session.

But increased competition is here to stay, experts said.

Expanded private school choice in places like North Carolina will ultimately force charters to “sharpen their value proposition to educators and families,” Ziebarth said.

Friend expressed a similar view, positioning the present moment as an opportunity for charter operators to refine their offerings. The choice that defines and drives charter schools, he noted, cuts both ways.

“I don’t think we’re going to see a slowdown in the demand that parents have for choice [and] the appetite for policymakers to give them that option,” he said. “As charter school operators, we need to focus on being the best that we can be for our school and give parents a reason to choose us — but also understand that they may choose someone else.”

Editor’s Note: EdNC has retained Kristen Blair to cover charter schools. Kristen currently serves as the communications director for the North Carolina Coalition for Charter Schools. The National Alliance for Public Charter Schools, referenced in this article, serves as a resource for state charter organizations. Kristen has written for EdNC since 2015, and EdNC retains editorial control of the content.

This article was updated on Aug. 21, 2025, to clarify the factors impacting the drop in schools.

Recommended reading