At the start of the semester last school year, a North Carolina high school teacher recalls sitting in the back of her lab for what would have been a normal planning period.

“I hear someone hollering my name,” she said, remembering it stood out to her because they were yelling her first name in a panicked voice. (For the sensitive information shared about a student in this story, she has requested to share anonymously.)

A student rushed her to another teacher’s classroom, saying they couldn’t wake someone up.

“When I got there, this young gentleman was passed out on the desk. He was clammy. He was pale, lethargic, and drooling,” said the teacher, who is a registered nurse and teaches the Nursing Fundamentals class. The student was non-responsive to the two teachers tapping him and asking if he was okay.

“While all this is happening, I start asking the students, ‘Is he diabetic? Does he take any medications?'”

No one responded as she tested the student’s blood pressure and heart rate, which, at first, were fine.

“He just wouldn’t respond,” she said, even after performing a sternal rub, which would normally cause someone to react due to feeling painful stimuli. “They should respond to that, so he wasn’t responding to pain,” she said.

She told the student’s teacher to call 911 immediately, one student was instructed to go to the office to get an AED (automated external defibrillator) in case the non-responsive student stopped breathing, and the other students were cleared to another classroom.

When paramedics arrived, the student started responding to pain again, but his blood pressure and heart rate both started to drop, and he was still drooling. As she helped load the student onto the stretcher, something fell out of his pocket.

“I said, ‘Wait a minute, here’s his USB drive,'” she said, asking paramedics where to put it along with the student’s cell phone.

That’s not a USB drive, she was told by one of the student’s close friends who had stayed behind to make sure he was okay. “That’s a Juul.”

The student explained it was a type of electronic cigarette.

“What do you mean?” the teacher asked her. “What was in it?”

The teacher said she never found out for sure what caused the student’s state, but says the student had walked into the classroom totally fine. He had asked to use the restroom and after coming back to class, became non-responsive at his desk —which is when she was called for help. She believes he went to the bathroom to vape and experienced the harmful reaction to something he inhaled.

But since Juul cartridges — called Juul pods — are nicotine-based cartridges, the student would have had to modify the pods with other liquids to have such a dangerous response. This is possible. A quick search through online forums like Reddit and Quora brings up posts like “Every Juul hack I learned,” which acknowledge that “many people like to refill the pods with other brand juices.” Other brands of vape devices come in a “fill-your-own-tank” model, for various e-liquids.

There have been other cases of students vaping substances, sometimes very dangerous substances like synthetic marijuana, at schools across the state. While these situations are often under-reported due to the sensitive nature to both students and schools, several teachers commented in our teacher survey that they were aware of students who had dangerous reactions after vaping. Educators shared symptoms caused by students vaping unsafe products, including projectile vomiting, unsteady walking, spacing out, fainting, seizures, and more. In this week’s student vaping series, we also shared information about how Cabarrus County Schools stepped up disciplinary action after 14 students had to be sent to the hospital due to vaping synthetic substances laced with even more harmful illicit drugs.

Earlier this year, federal regulators also cracked down on another dangerous public health issue related to e-cigarette products: e-liquids made to look like juice boxes. One study, published in Pediatrics, analyzed liquid nicotine exposure data from the National Poison Data System and found that there were “8,269 liquid nicotine exposures among children <6 years old reported to US poison control centers” from January 2012 to April 2017. Severe adverse effects resulting from very young children drinking the e-liquids included cardiac arrest, coma, seizures, and respiratory arrest. In one case, a one-year old boy died.

But what about when middle and high school students vape the proprietary, flavored nicotine-based products sold by e-cigarette companies online and in stores?

While e-cig makers market their products as a way for consumers to wean off of more harmful burning cigarettes, the current epidemic of youth users poses a new dilemma: minors addicted to nicotine and limited data on the potential long-term effects of continued use of e-cigs.

Health Education and Intervention

Since the high school teacher and registered nurse came to the aid of the student found non-responsive, the school has made announcements about vapes to raise awareness. The teacher remains concerned that not enough has been done to warn students of potential dangers, but says that it at least made teachers aware of vape products.

“It probably helped the teachers that had no clue what a Juul was like me,” the teacher said. “I didn’t know what a Juul was until I started researching it.”

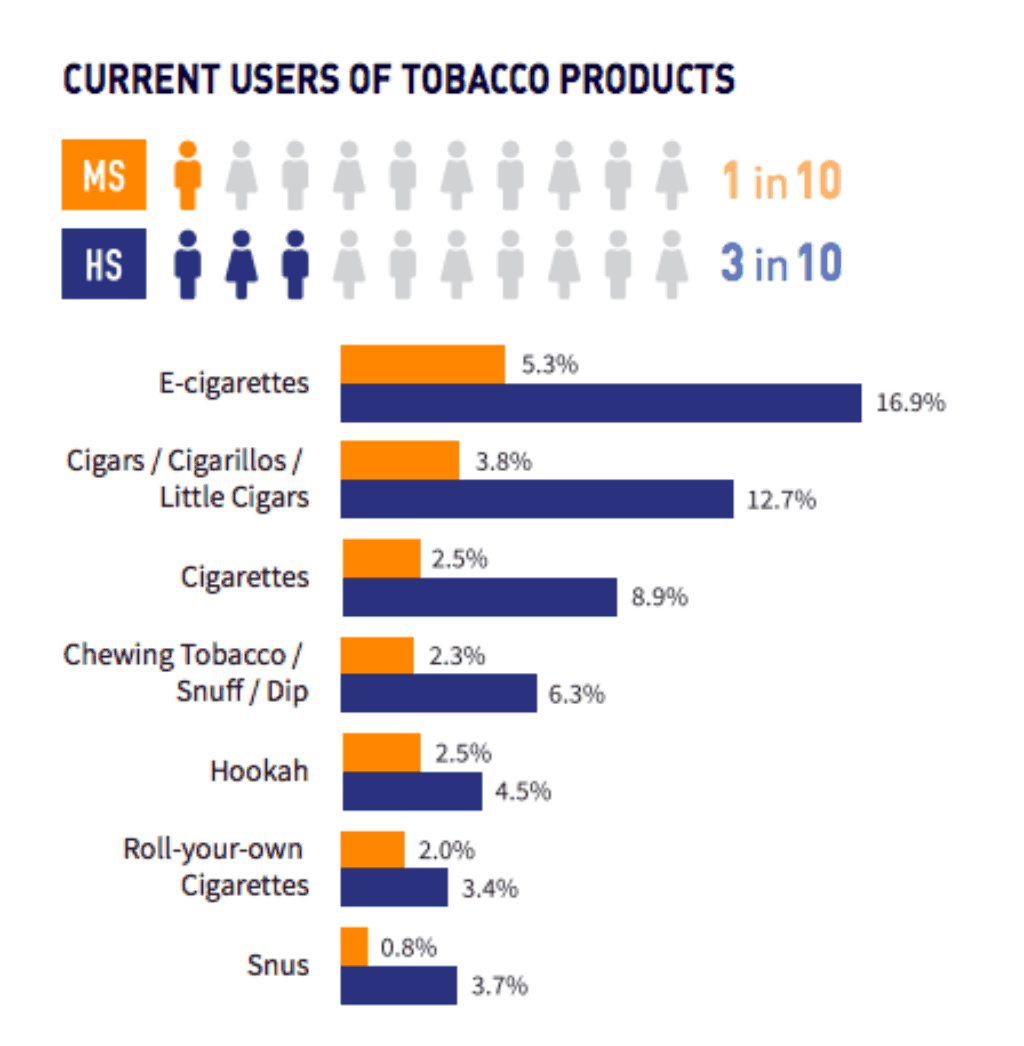

In our survey with more than 1,400 North Carolina teacher responses, 57 percent said that their schools had not implemented health education efforts to inform students about vaping. This is despite that fact that the 2017 North Carolina Youth Tobacco Survey showed that 5.3 percent of middle schoolers and 16.9 percent of high schoolers used e-cigarettes — a number that has likely increased. The 2018 National Youth Tobacco Survey found that 1.5 million more students used e-cigarettes in 2018 than in 2017.

“More recently, it has been harder to catch those who vape (Juuls, etc.) in class,” wrote high school English teacher Joshua Smith in follow up from our teacher survey. “There is no schoolwide address of it on a health or club level.”

Officials in North Carolina are working to change that.

“We have been presenting and providing educational materials at statewide, regional, and local conferences and training events across the state … especially this past year,” said Jim Martin of the Department of Human Health and Human Services (NC DHHS), who directs policy and program development at the Tobacco Prevention and Control Branch.

“The other thing that we’re also doing is supporting the national efforts through FDA and CDC with their educational materials,” Martin said. “For example, FDA is now sending … educational posters on e-cigs and the health risks that they bring along to schools that are designed to be put up in bathrooms.” School bathrooms have proven to be a popular space for students to vape during and between class. DHHS’s dissemination of those posters will continue this winter.

(More education materials and information on youth vaping from the CDC here and here. The FDA announced its “The Real Cost” vaping prevention campaign in September and carried out a crackdown on e-cigarette companies earlier this year.)

DHHS is currently working to have schools update their tobacco-free campus signs to reflect the prohibition of e-cigs, and Martin added there is space for health education efforts in disciplinary measures for students caught with vapes on campus, like in-school suspension.

“Our division has really recommended … in coordination with DPI, that there be an alternative-to-suspension program that uses an educational program called ASPIRE,” Martin said. “We feel that education is a real key here, and part of this process for enforcement should be focused on education, rather than just all punishment.”

Working in close partnership with DHHS on the issue of student vaping is the Department of Public Instruction (NC DPI).

“The Healthful Living Standards address the skills necessary to avoid those behaviors,” said Ellen Essick, section chief of NC Healthy Schools at DPI, of e-cig use. “It’s one thing to teach the content about how bad a Juul is for you, but more importantly, we want to teach the decision-making skills and the refusal skills — the skills students would need to not begin using those substances.”

Those decision-making skills are a priority in Taryn Shelton’s eighth grade science class at John Griffin Middle School in Cumberland County. Shelton incorporates a Healthy Living Unit and conducts a day-long peer pressure activity with her eighth graders focused on drug prevention.

“Eighth grade’s kind of like that pinnacle year,” Shelton said. “We’re getting them ready for high school, and once they get to high school, they’re on their own. … So we spend more time talking to the kids and teaching them and developing their character before we send them on to high school.”

This year, she wanted her eighth graders to know more about vaping.

“I didn’t really have [many] facts about vaping because it’s still kind of new,” Shelton said. “But within the last couple years, it’s kind of really blown up … This is the year that I really see a lot of teens doing it and engaging in it, and it’s in the news.”

Now her peer pressure activity includes a scenario that says, “You’re hanging out with your friends and a couple of them are vaping and one is smoking cigarettes or using smokeless tobacco. You want to fit in and not look baby-ish. Most teen starts smoking cigarettes because other teens smoke, and they appear to look more grown up. Many teens think vaping is safe and are attracted to the flavorings. Some even add marijuana or alcohol to vaporizers …”

Students are also given a fact sheet on each type of drug. This year, Shelton expanded her note on e-cigarettes to include the terms “vaporizers” and “Juuls.”

“I added to that: Vaping can lead to smoking later in life. Vaping can create nicotine dependency in teen brains… Nicotine addiction can lead to mood disorders,” she said.

Her list, drawn from the CDC, went on. It highlighted that just because e-cigs are marketed as safe alternatives to smoking, it doesn’t exactly mean they are safe — especially for kids.

What’s even in a vape?

E-cigarettes are used to vaporize e-liquids, which are often flavored and often contain nicotine. But what does that really mean? What’s actually in a branded vape product?

“Each liquid is actually a different blend of substances, and I think that’s actually one of the difficulties that the medical part of the research has in standardizing things — because a lot of different brands have a lot of different compositions for the liquids,” said Coral Giovacchini, a pulmonologist at Duke Health. As a physician specializing in pulmonary medicine, which is anything to do with the lungs, she regularly sees patients for asthma, COPD, and smoking-related lung illnesses, including lung cancer.

“I would say it’s typically a mix of propylene glycol, which is kind of like a carrier fluid; vegetable glycerin, which is usually something that’s classified as non-harmful or safe as an edible substance; and then a mix of either nicotine, or not, and flavor chemicals, or not,” she said of most e-liquids.

At surface level, the ingredients don’t sound too harmful — especially in comparison to carcinogen-laden cigarettes —but Giovacchini highlights some warnings.

“We know some of the effects of the various components of that liquid and then also some of the social habit-forming effects that even using a vape can have,” she said. “In terms of the health effects they have that we know, there are some studies that are published, especially in kids with asthma — and kids without lung-related symptoms — that they can develop asthma-like symptoms when they’re inhaling something.”

This was the case for Chase, a tenth grader in Cumberland County, whose name has been changed. He was introduced in our regulation story in this series.

Chase is a swimmer, and even though he started vaping Juuls just six months ago, he said he felt the difference as an athlete.

“It would affect your breathing,” he said.

A study released last year in the American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine concluded that “adolescent e-cigarette users had increased rates of chronic bronchitic symptoms.”

Giovacchini said there is also research about the chemical flavorings, and that different flavors — particularly flavors that tend to be cream-based or cinnamon-based — can have some asthma-like effects in a spectrum up to bronchiolitis obliterans, more commonly called “popcorn lung.” She said symptoms of the lung disease often start as pneumonia-like symptoms and then in the long-term become shortness of breath with exertion and wheezing.

The American Lung Association describes popcorn lung as “a scarring of the tiny air sacs in the lungs resulting in the thickening and narrowing of the airways.” The organization has known about the consequence from e-cigarettes as early as 2016, and even filed a lawsuit against the FDA for not taking action on e-cigarette flavoring chemicals sooner. Organizations like the American Academy of Pediatrics, American Cancer Society Cancer Action Network, and American Heart Association, among others, also joined the lawsuit.

Even though we know that diacetyl causes popcorn lung, this chemical is found in many e-cigarette flavors https://t.co/w3G3WJQMdM

— American Lung Assoc. (@LungAssociation) July 8, 2016

“The party line on lung health is if you can avoid inhaling something, it’s probably best not to,” said Giovacchini. “Even the vegetable glycerin, which is classified as a safe-to-eat substance by the FDA … it’s probably not great to inhale a fatty substance in your lungs.”

But there’s another ingredient that’s cause for concern in light of the surge of young people using e-cigarettes: nicotine.

E-cigs, sometimes referred to in studies as “electronic nicotine delivery systems (ENDS),” contain varying levels of nicotine. For example, blu e-cig cartridges have a range of nicotine content from 1.6 percent to 2.4 percent. Juul hit the market in 2015 with double the amount of nicotine as other cartridges, with Juul pods packing a 5 percent punch. One single Juul pod contains the same amount of nicotine as 20 cigarettes.

While Juul packaging, like many e-liquid products on the market, comes labeled with a nicotine warning that reads, “Warning: This product contains nicotine. Nicotine is an addictive chemical” — a Truth Initiative study reported that 63 percent of Juul users “don’t know that the product always contains nicotine.”

The consequence? Students are getting hooked.

“This semester I caught two of my students vaping in the dressing room before class. These students are really good students,” wrote one dance teacher, following up from our teacher survey, and requesting anonymity. “I never have any issues with them whatsoever. I’ve actually been teaching them for years.”

“It was at that moment that I realized just how big of a problem ‘vaping’ has become. It is so addictive for so many,” she continued. “Personally, I am also having an issue with my step-child vaping. Unfortunately, it is too easy to hide. I fear we are continuously having issues because she is addicted and cannot stop. SO many kids are doing it that it appears to be the norm to them.”

But there are schools challenging the student vaping norm. Earlier this week, we wrote about how a high school newspaper in Kill Devil Hills tackled the growing problem by making the issue of Juuling their front page story. Meanwhile in another part of the country, one Massachusetts high school took direct action on a popular vaping hideout: the restroom.

“A month ago, they took the bathroom [entry] doors off the bathrooms,” said Spanish teacher Sarah Merullo of Ipswich High School. “I just spoke to the assistant principal earlier today, and he said that no one’s gotten in trouble for vaping since that happened.”

“Obviously, that doesn’t mean it’s not going on,” she added. “But it’s less of an egregious problem … It was just rampant, and everyone was just leaving class to go to the bathroom to vape.”

The fact that students sometimes can’t make it through class without the urge to vape demonstrates the worry many public health officials have: they’re already addicted.

At his high school in Cumberland County, Chase said he often hears students asking each other about the percentage of nicotine in their vapes.

“They don’t want to hit it if it doesn’t have nicotine,” he explained.

He also said he knows what an addicted student looks like.

“I’ve seen people that are really addicted. They’ve been caught several times so they don’t have their own anymore,” Chase said. “And they’re shaking and asking constantly, ‘Do you have a Juul? Can I have a hit?'”

The CDC holds that nicotine is unsafe for teens for several reasons, including:

>Nicotine can harm the developing adolescent brain. The brain keeps developing until about age 25.

>Using nicotine in adolescence can harm the parts of the brain that control attention, learning, mood, and impulse control.

>Each time a new memory is created or a new skill is learned, stronger connections – or synapses – are built between brain cells. Young people’s brains build synapses faster than adult brains. Nicotine changes the way these synapses are formed.

>Using nicotine in adolescence may also increase risk for future addiction to other drugs.

“If nobody’s teaching it, then they don’t really understand what’s going on,” said Health and P.E. teacher Leah Mullen of Cox Mill High School in Concord.

For Mullen, integrating education around these issues of vaping was a no-brainer.

“The next unit we’re about to teach is ‘alcohol, tobacco, and other drugs’ and we usually try to tie vaping in with it,” Mullen said. “We talk about it throughout the semester … just as much as we can, because it’s so big.”

According to Mullen, one of her health class activities showed her how prevalent vaping among high schoolers actually is.

“I’ll have them all close their eyes,” she said, adding that she asks students to put their heads down and reminds them she’s not judging them based on their responses. “I’ll ask them how many have smoked cigarettes, how many have drank alcohol, how many have smoked weed…”

She watches how many hands go up for each instance.

“When I bring up vaping,” Mullen said. “It’s the whole entire class.”

Recommended reading