Long before COVID-19, EducationNC was interested in innovation. More specifically, we were interested in when innovation bubbles up from our classrooms and our schools versus when “innovation” is pushed into our classrooms and our schools by a district or the state.

Singapore does both. Some schools serve as laboratories of innovation, and then once the country has identified and is ready to scale a best practice, it is pushed into all of the classrooms in all of the schools across all of the country in one fell swoop.

During COVID-19, with classrooms, schools, and districts under unprecedented stress, we saw a wide range of reactions to the idea that the pandemic could be the disruptive event that would spur innovation and radically reshape the student experience of education going forward.

Remember this tweet from Watauga County Superintendent Scott Elliott in the early days of COVID-19? It resonated with many educators.

Now, many wonder if the education system missed the moment. A recent headline in The 74 read, “Restaurants Innovated as a Result of COVID-19. Education Largely Did Not. In Our Relief Over the Pandemic’s Coming End, the Opportunity May Slip Away.” The author, Andrew Rotherham, is a founder and partner at Bellwether Education, a national nonprofit working to support educational innovation and improve educational outcomes for low-income students. He wrote, “we need big ideas about how to go from a system that requires students, teachers, and families to be extraordinary in order to thrive to one that is itself extraordinary — nimble, resilient, and equitable.”

Because we visited 34 school districts during COVID-19, we knew many of our classrooms and our schools and our districts were being innovative. But over and over again, we faced an old problem.

North Carolina doesn’t have an infrastructure for innovation.

Unlike Singapore and some other states, we don’t have a comprehensive way to identify, assess, share, and then scale best practices across the state.

One of the most anticipated returns on the state’s investment in charter schools was the innovations from the experiment. In the original legislation, one of six purposes was to “encourage the use of different and innovative teaching methods.” Charters were expected to share with traditional public schools the successes and failures so those could either be replicated at scale or avoided at all costs.

But the state did not build the infrastructure to scale innovation among charters, between charters and traditional public schools, or among traditional public schools.

Without that infrastructure, educators miss out on a comprehensive understanding of all of the innovations happening across the state, miss out on the opportunity to create virtual professional learning communities with other educators outside of their schools, and miss out on the opportunity to visit other schools to not just imagine what is possible but to better understand how to make it happen.

David Stegall, the deputy superintendent of innovation for the North Carolina Department of Public Instruction, is fixing to change that.

Enter the Canopy Project

The Canopy Project “is a collaborative effort to surface a more diverse set of innovative schools.” It started in 2019, and it is led by Transcend Education and the Christensen Institute. “The Canopy Project allows education leaders, school designers, and researchers to see both the ‘trees’ — individual schools — and the whole ‘forest’ of schools that are innovating,” says the website. This helps us see the “rich biodiversity” of innovation across states and the country.

Eight schools across North Carolina are in the Canopy Project: Charlotte Lab School, Evergreen Community Charter School in Asheville, North Edgecombe High School, Northeast Academy for Aerospace and Advanced Technologies (NEATT) in Elizabeth City, Park View Elementary in Mooresville, South Rowan High School, Southeast Area Technical High School (SEA-TECH) in Castle Hayne, and Tri-County Early College in Murphy.

Take a trip through the canopy — the interactive national database. First, go to the website. Scroll down, and then next to “Want to search for innovative schools?” click “Go.” Then click on the red button that says filters. Under state, click North Carolina. Click “close filter pane” to see the North Carolina schools. You can hover on the name of each school for more information, and you can click to expand the table to see even more.

Scroll down this webpage to see a list of nominators for the Canopy Project, which includes a number of North Carolina organizations such as the Friday Institute for Educational Innovation, NC Digital Learning Institute, Center for Teaching Quality, Open Way Learning, and Public Impact.

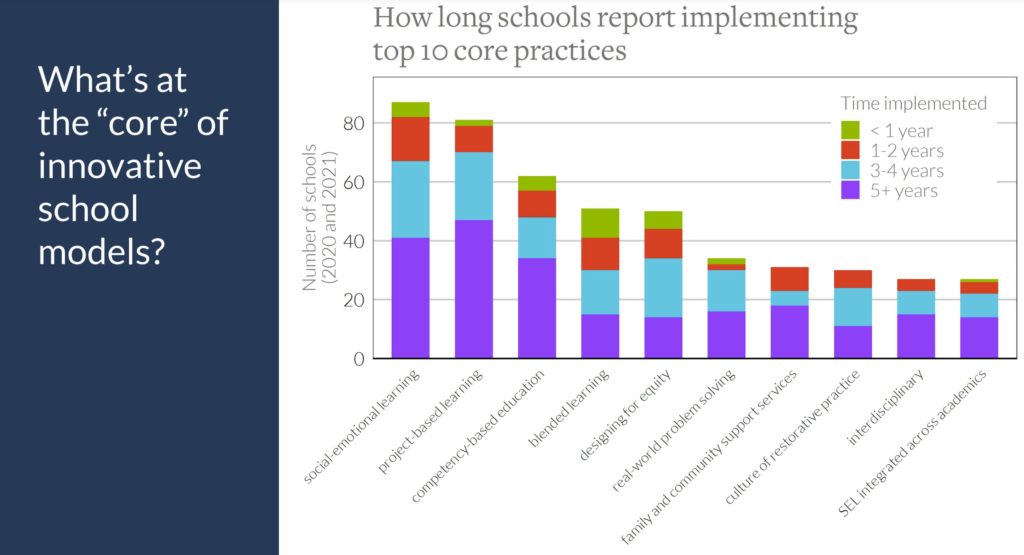

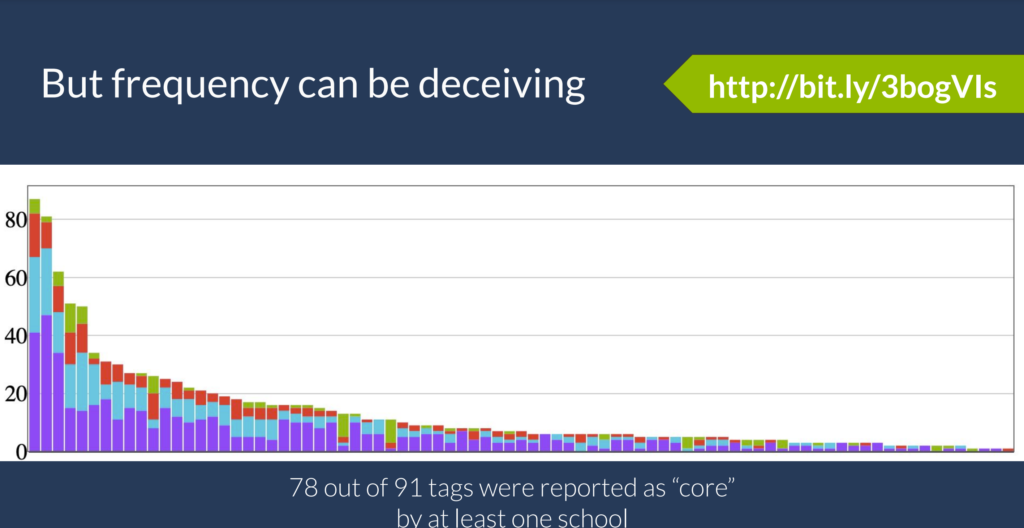

To date, 121 nominators have nominated 483 schools across the United States, and 222 schools have submitted data for the database. Here is the methodology of the project, here is the survey sent to schools that are nominated, here is the data from 2019, here is the data from 2020, and here is a complete list of the 91 tags used to identify innovative practices including descriptions. Schools identify all the innovative practices they implement, the “top 5” core to their school DNA, and how long each practice has been implemented. Longer term, the project will be able to track when and why practices are abandoned.

We wondered if the schools across North Carolina knew about each other, we wondered how many educators across the state even knew about this database, and we wondered if other schools or districts might like to visit these and other innovative schools in North Carolina if they had the opportunity.

Right around the time we were imagining if this could be a way to ignite a conversation about the infrastructure needed to scale innovative practices across the state, this article about the Canopy Project was published in The 74 on Dec. 6, 2020. I tweeted it, David Stegall saw it, and then he and Angie Mullennix, director of K-12 Academics and Innovation Strategy at DPI, reached out. We decided to visit all eight schools.

Each visit includes a conversation with school leaders, a focus group with teachers, a focus group with students, classroom visits, and an opportunity to debrief and ask follow up questions, all designed to help us better understand the innovative practices listed for each school in the Canopy Project database.

It is important to note that there are other national level efforts mapping innovation in our schools, including among others the Innovative Schools Network, Teacher Powered Schools, and Education Reimagined’s Learning Environments Map.

“Innovation is possible in any school in America” — and North Carolina

Recently, Mullennix and I presented our approach on a national webinar hosted by the Aurora Institute. Here is more information, including the slide deck.

Chelsea Waite with the Christensen Institute who studies student-centered learning shared a simple conviction: “Innovation is possible in any school in America.”

She said part of the problem when it comes to innovation in classrooms and schools is that “what you know depends very much on whom you know.” So while the experience of some innovative schools goes viral, the experience of many other innovative schools remains below the radar — and the result, said Waite, is missed opportunities.

The Canopy database, said Waite, helps us think about our “mental model of innovation.” What counts as innovative? Who gets to decide? If a practice has been around for a long time, does that mean it doesn’t count? Does it have to be disruptive to be innovative?

The Educational Innovation Network NC

Back in 2019, around the same time the Canopy Project was getting underway, a group of about 50 educators founded the Educational Innovation Network NC. Here you can see their vision, mission, core values, and the members. You can follow the network, born of research and convenings on innovation by Robert Smith and Kayce Smith at the Watson College of Education at UNC-Wilmington, on Twitter @InnovateEduNC.

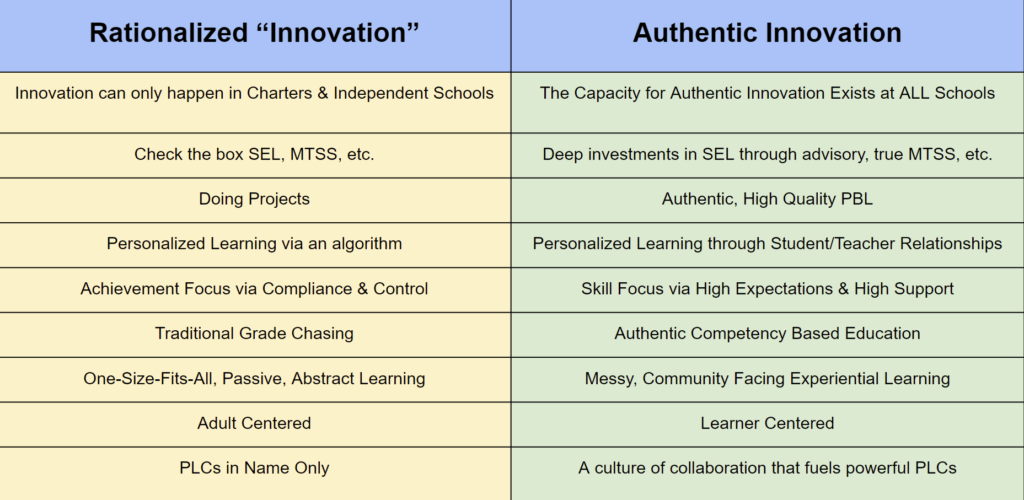

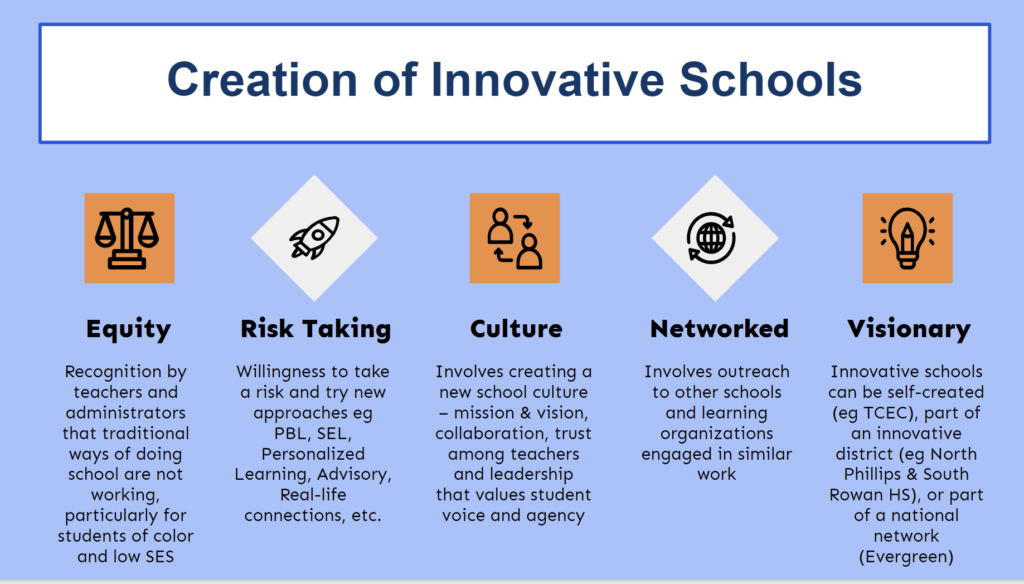

The network also believes that “the capacity for authentic innovation exists in ALL schools,” and it collaborates with schools in the Canopy Project as well as other state and nationally recognized schools that embody an innovation culture.

Here are some ways the network thinks about what counts as innovation.

Understanding our own canopy

At our first school visit to Evergreen Community Charter School in Asheville, Stegall said practices that are good for all students need to be identified — and we need to understand how to implement the practices with fidelity in all schools.

“How can we not leave things to chance?” he asked.

Stegall talked with school leaders about “education roulette.”

“We look at the end user, which is the student. Our focus is making sure we are not leaving a student’s quality education to chance,” he said.

Mullennix said any promising practice that helps a school address a challenge counts as innovative. She said her hope is an even more robust and expansive database for North Carolina so an educator in Cherokee County can identify practices in a classroom or a school 503 miles away on the other side of the state.

We know there are many innovative schools and districts in North Carolina that don’t make national lists. For example, tomorrow EdNC will release a short documentary about schools in our renewal district, the Rowan-Salisbury Schools.

If you know of a innovative practice you’d like us to know about, email me at mrash@ednc.org. To understand our own canopy, we need to identify all of the trees so please reach out.

Follow us on Twitter while we travel @davidstegall, @DocAngMullennix, and @Mebane_Rash.

Recommended reading