What would a school look like if it was designed, from the ground up, by the students in its classrooms?

That was the question a team of educators in rural Edgecombe County started asking themselves two years ago. The schools in the county’s Northside district have long struggled with low student performance, attendance, graduation rates, and more. It was time to create something different for students, as something about the current system clearly wasn’t working well enough.

“This is a place that we had, pretty consistently, very high turnover in staff,” said Erin Swanson, director of innovation for Edgecombe County Schools. “Low student achievement … we were talking about scores that were 10% proficient, maybe 20% proficient, but persistently low-performing.”

That’s part of what prompted the collaboration between Swanson; Valerie Bridges, the district superintendent; Donnell Cannon, principal of North Edgecombe High School; and Jenny O’Meara, principal of Phillips Middle School.

There were a few factors that emboldened the team to create a whole new school rather than implementing smaller changes. Nearby Martin Millennium Academy, a school in Tarboro with a Spanish-immersion program, had succeeded in bringing families back to the public school system by using new, innovative models. This model was something that already existed in a few other North Carolina counties, but it was new for Edgecombe County and had a positive impact in the area.

There was also an opportunity to become a Restart school, which gave administrators charter-like flexibility without giving up the opportunity to serve lower income students. Becoming a Restart school means reworking existing school facilities to serve the same group of students in a new way. The Edgecombe team created a “micro school,” a pilot program that would be located on an existing high school campus but start by serving just 30 students.

The first step in that process? Listening.

The team conducted empathy interviews with students and parents, asking them what they wanted and needed in a school. Many students said the material they learned in classes wasn’t applicable or useful in real life. They also wanted more social-emotional connections in school, expressing a desire to be more open with their teachers and feel free to talk about things that were happening outside of the classroom.

What emerged from those conversations was a portrait of a student who was three-dimensional — a student with needs, wants, hopes, and dreams; a student with profound experiences, good and bad; and a system that they couldn’t relate to. Traditional school just felt too far removed from their own realities. Parents said they wanted more opportunities — and better opportunities — for their kids to prosper.

From the interviews and listening sessions, the team, in collaboration with the community, set a baseline goal that ultimately drives all their innovative work around educating children in schools. That goal is this: By age 25, every individual should be pursuing something they’re passionate about, aware of their agency in the world, and using their abilities to create positive change.

In addition to conducting local research, the Edgecombe team visited innovative schools across the country looking for ideas to adapt. In these classrooms, they observed innovative approaches and took notes.

“We had lots of chart paper that was all marked up and thought through,” said Bridges. “We would process, we would think on it, we’d come back to our next session and tear away everything we had and start over.”

All of this research eventually culminated in a list of several innovative components that, together, create the North Phillips School of Innovation. It’s a radically different approach to teaching the same standards as the rest of North Carolina’s public schools. Many of these elements trace back to this concept of fostering an environment where students feel loved and supported by their peers.

EdNC filmed students at the school for its pilot year in addition to giving the students two video cameras to film with. You can see the story in our new short film, We Drive It — Inside the North Phillips School of Innovation.

Meta Moments

This exercise is focused around ideas of meditation and reflection. An unfortunate reality is that many students in the Northside feeder pattern of Edgecombe County experience poverty and trauma at higher rates than the average student. Studies increasingly show that what happens at home has a significant impact on a student’s ability to excel in the classroom.

Meta Moments give students a chance to process the complex emotional experiences to which they may be subjected. It gives them space to check their emotional head space, reflect on their role in the world, and simply recognize their own existence before sitting down to focus on a math problem or other bit of schoolwork that feels meaningless and far removed from the clutches of reality.

Students write down their reflections in journals, and entries can be designated as something to share with the whole class or only a teacher. Each student has a chance to think about their current state, put their thoughts to paper, close the notebook, and move on with a fresh mind — a practice backed by both common sense and science.

Affirmations

Each morning, students are given an opportunity to verbally affirm themselves or their peers for a job well done. Sometimes that can mean a self-congratulation for catching up on a project. It could also mean recognizing another student who provided emotional support in a time of need. The students speak candidly about their appreciation for each other and highlight others’ successes.

In addition to the verbal component, the wall of the school’s main classroom features a large collection of cork boards with “Affirmations” written above. Each board is dedicated to one student and functions as a place where peers or teachers can pin affirmations. The result is a colorful wall of positive words and a constant reminder of the love and support offered in the space.

Students also have more subtle opportunities to affirm each other throughout the day, particularly in a community sense. At the beginning of the year, the students were grouped into one of three “houses” a la Hogwarts. The students experience pride and a sense of belonging based on their affiliation. Engaging in friendly competition between groups fosters cooperation and builds trust.

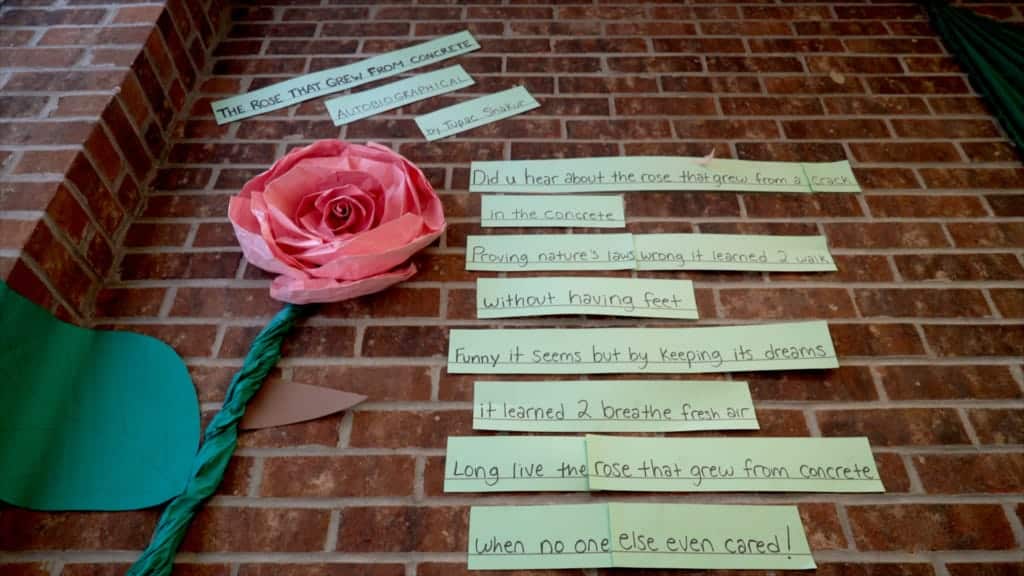

Roses In Concrete

Once per week, students attend a session called Roses in Concrete. This is a curriculum centered around identity, culture, and self-actualization. Students learn about oppression and privilege with the hope that one day, if they are ever marginalized for their identity while pursuing their dreams, they will have the knowledge and tools to navigate the situation successfully.

Students aren’t just learning about historically oppressed groups, they’re learning how to understand their own agency and take charge of their destinies. They’re learning how to be respectful to people they disagree with while owning their identities and understanding all of the cultural expectations that may come along with them.

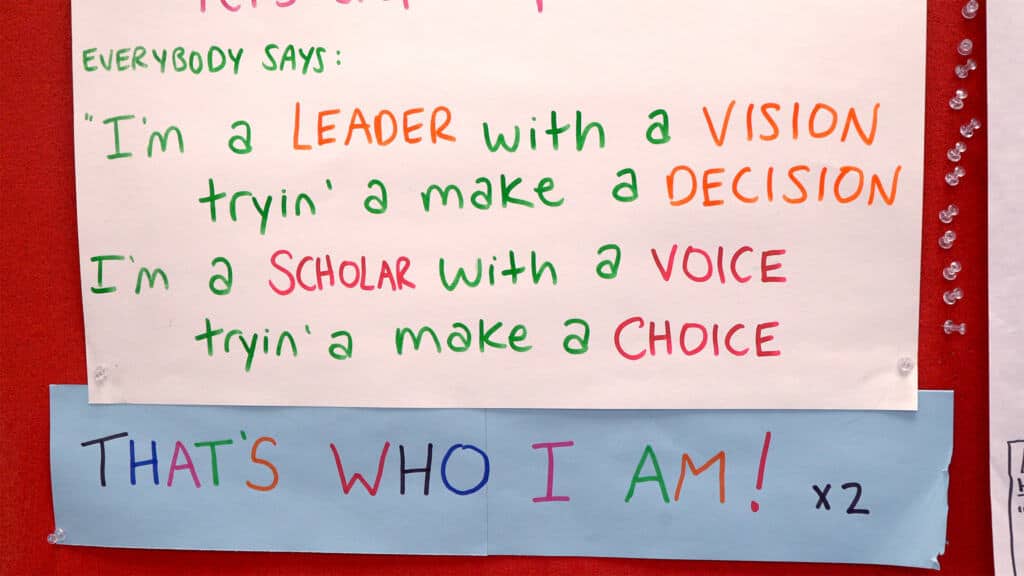

These themes of identity and agency don’t go away after Roses in Concrete ends each Wednesday. In the classroom, students sometimes perform a chant called “That’s Who I Am.” It’s a rap centered around the concept of having a plan and executing it rather than passively waiting for life to begin or for circumstances to change. After a unison chant, students take turns saying a sentence that describes a positive trait of theirs.

“I am brave!”

“I am smart!”

“I am amazing!”

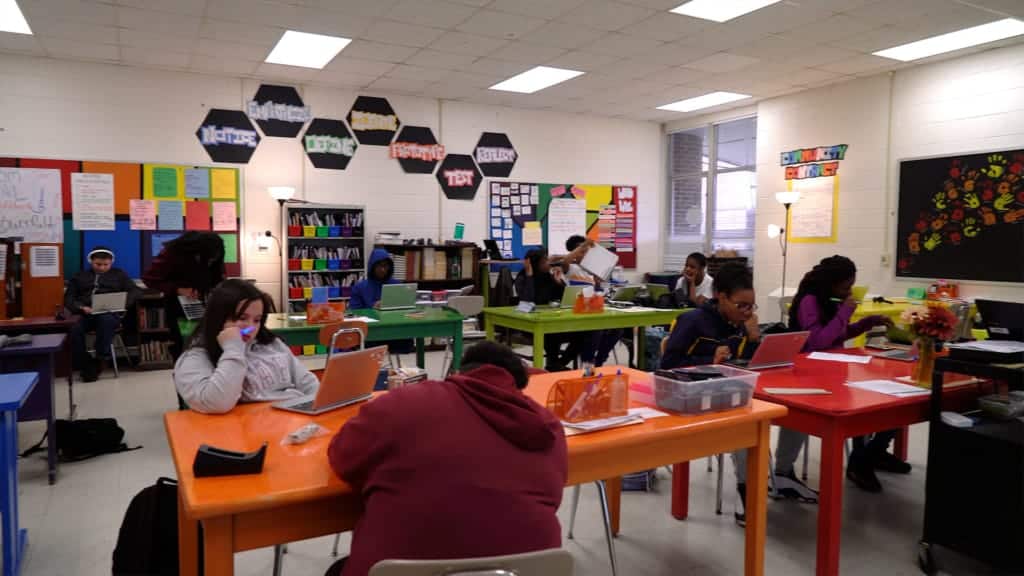

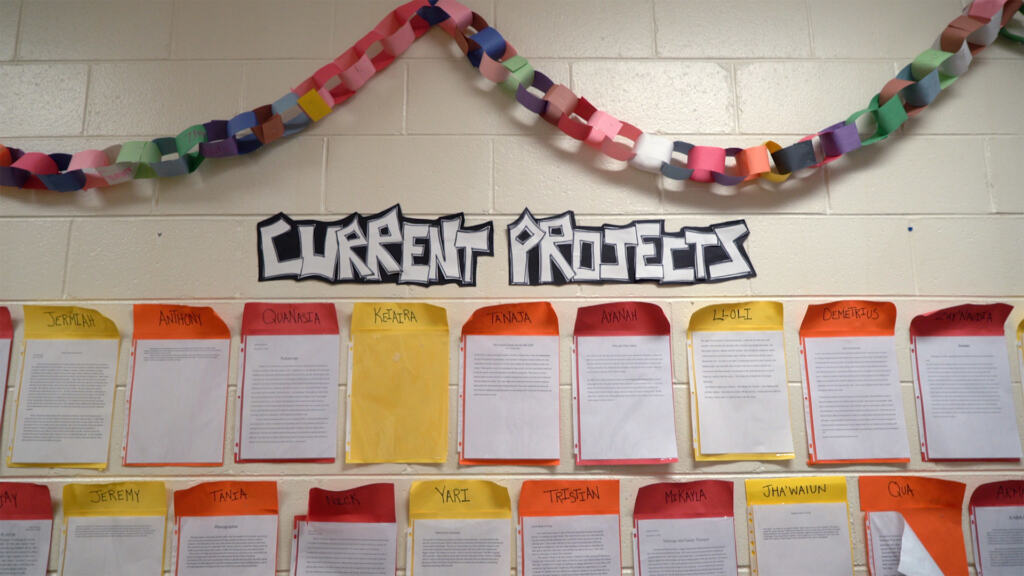

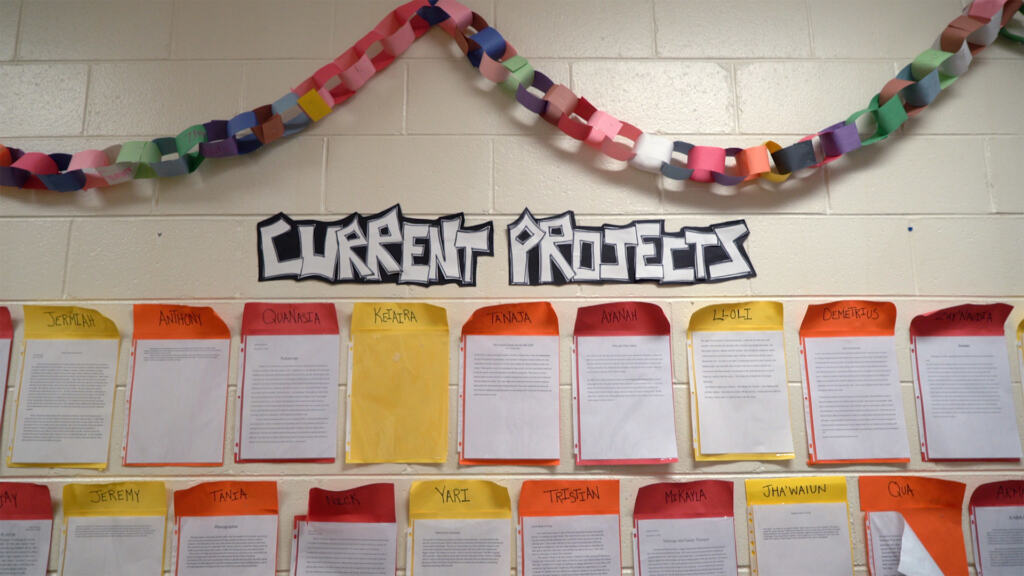

Passion Projects and Standards Labs

Students primarily learn academic standards by completing passion projects. The “passion” element is critical and is a direct response to students who said that school felt irrelevant to their lives. The goal is to expose students to brand new passions they weren’t previously aware of, and then connect those dots to a profession the student is genuinely excited about — something that could give them a good enough reason to stay in school and reach higher, professionally or academically.

One staple of passion projects is flexibility on the part of the teacher to tailor the project to the individual student. If there is another way to teach the same concept that will resonate better with one specific student, within reason, that student’s project requirements are tweaked to better suit them. This is especially important in a class with students whose academic performance and behavioral temperaments vary widely. In the School of Innovation, there are EC learners in the classroom right alongside AIG learners. Every student will not find the same things interesting.

“We don’t want them to go to college just to go to college,” O’Meara said. “We want them to go knowing that they love something in this world, and they want to put a mark on something.”

The original dream for the School of Innovation was to have no classes at all — but rather to cover the whole curriculum with project-based learning. The team soon discovered, however, that using solely projects to cover the required math standards, along with some portions of other subjects, was quite difficult. For now, the solution is to fill in the gaps with “Standards Labs” where students can access this content at their own pace. Wrapping all the standards into a project-based approach is still a long term goal for the school.

The result: Self-actualization

Together, these exercises teach the importance of individuality, but also what it means to be part of a collective. They teach students how to accept and manage life circumstances that cannot be changed, but also empower them to make better decisions when they can.

What does this all mean on a practical level? It means students are more aware of who they are, what they want, and how they might go about achieving it. Or at least that’s how the students themselves have described the process so far.

At EdNC’s BRIDGE gathering in Greensboro, we premiered We Drive It — our documentary about the School of Innovation. Afterwards, four of the students from the school participated in a panel that took questions from the audience. More than anything, they talked about the emotional support and relationships fostered in the school and how it has changed they ways they think about themselves.

One woman asked the students if they thought all kids would benefit from a school like theirs. Darquavias Lancaster (the second student from the right) said yes, noting that at first, he didn’t want to go to the school, but the longer he stayed, the more he liked it.

“When I first got there, I used to just be a reactor,” said Lancaster. “If you’d say something to me, I’d just start blowing up at you. Now, I actually think about what I’m about to do, and the decisions I make.”

Students at the School of Innovation are being evaluated in several areas, from their ability to communicate with others to their competence in sending emails. To measure their social-emotional development, students take the Panorama survey and are regularly given similar survey questions. In many non-academic metrics, students have already shown a clear improvement: they come to school more and leave early less frequently. They get in trouble less often — even students who were “problem kids” regarding behavior have received significantly fewer disciplinary actions.

From an academic perspective, the students are responsible for taking the same End-of-Grade tests and meeting the same standards as the rest of North Carolina’s eighth and ninth graders. Throughout the pilot year, they’ve also taken the same standards tests as other students throughout Edgecombe County. According to Swanson, student scores at the School of Innovation have generally been equal to, or exceeded, other schools throughout the district.

The one exception was math performance, where students at the School of Innovation initially lagged slightly behind, leading the team to revert to a more traditional math class approach. But Swanson said she expects the overall improvements will be evident during end-of-year evaluations, noting that since things like ACT scores can be a gatekeeper for opportunities, it’s imperative that students do well on them — but that is likely, considering the evidence so far.

Beginning next year, every eighth, ninth, and 10th grader in the Northside feeder pattern (that’s eighth grade students at Phillips Middle School and ninth and 10th grade students at North Edgecombe High School) will have practices from the School of Innovation incorporated into their school days, including Meta Moments, Roses in Concrete, and Affirmations, along with a multi-classroom leader and other elements meant to give students the personal attention they need to pursue their passions. They’ll also work on interdisciplinary passion projects every day in Design Labs and Standards Labs.

Only time will reveal the ultimate impact of implementing such an approach on a wider scale. In 2022, the first class will graduate that experienced a full four years of innovative schooling. The passionate team in Edgecombe hopes that when those graduates are 25, they’ll be in a place they didn’t know was possible before, changing their world in ways they didn’t know they could.