Microschools, charter schools, district innovations, and other education models are expanding rapidly, but which one will lead the way? And how can parents and the public know which models are successful and scalable? Hundreds of researchers, educators, policymakers, and other K-12 stakeholders convened last month at Harvard University to address those questions at the fourth annual “Emerging School Models” conference.

Hosted by the Harvard Kennedy School of Government’s Program on Education Policy and Governance (PEPG), the conference is meant to provide “a big tent” for school choice, Paul Peterson, PEPG’s director, said. Key themes from this year’s conference were measuring performance and scaling success.

![]() Sign up for the EdDaily to start each weekday with the top education news.

Sign up for the EdDaily to start each weekday with the top education news.

Interest in this year’s conference was unprecedented, with 600 in-person registrants — “an all-time high,” according to Peterson — and 1,500 more watching online.

Robust parent demand has driven the urgency, as rapidly evolving policies have had a propulsive effect on the school choice movement. Emerging school models thus stand “at a critical crossroads,” as the conference’s framing language noted. As school choice policies create more ways to use taxpayer dollars, these models face “greater pressure to demonstrate success” — even as scalability and sustainability present ongoing challenges.

Conference speakers reinforced this theme: Change is a constant.

“Dynamism is the new sustainability,” Don Soifer, the CEO of the National Microschooling Center, said in the opening session. “We all need to understand that this (microschooling) is just fundamentally different.”

Yet, even as education savings accounts (ESAs) and other school choice options have increased across the country, charter enrollment has also continued to grow, said Eric Paisner, the chief operating officer at the National Alliance for Public Charter Schools. “Demand is there.”

“There’s a reason why so many parents are flocking to charters from traditional district schools, or to a microschool or other innovative models, or homeschooling,” said Daniel Weisberg, formerly the first deputy chancellor at the New York City Department of Education. “They’re not getting what they want.”

But Weisberg had a word of caution for school choice advocates: “We will ignore the health of traditional districts and district schools at our peril.”

“In some ways, we’re all going to succeed together, or we’re going to fail together,” he said. “We have to figure out how the ecosystem works.”

To that end, panel discussions centered around key components of the current ecosystem: leading choice models, learner-centered education, charter schools, state policies, accreditation, and more.

Keynote sessions — featuring Jeff and Janine Yass, founders of the Yass Prize; Melanie Lundquist, co-founder of the Partnership for Los Angeles Schools; and Los Angeles Unified School District (LAUSD) Superintendent Alberto Carvalho — addressed the role of philanthropy in education innovation.

Leading school choice models

In the conference’s opening session, national leaders shared insights addressing which model will “lead the way,” as the school choice movement advances.

Microschooling is still in its early adoption phase, said Soifer, accounting for approximately 2% of market share in the U.S.

The National Microschooling Center defines microschools as “small learning environments serving learners from multiple families.” Microschools can be public or private, and they may also offer students hybrid learning opportunities. As Soifer has noted previously, many microschools are simply “updated versions” of the one-room schoolhouse.

“It’s the flexibilities that really drive why families choose” microschooling, he said.

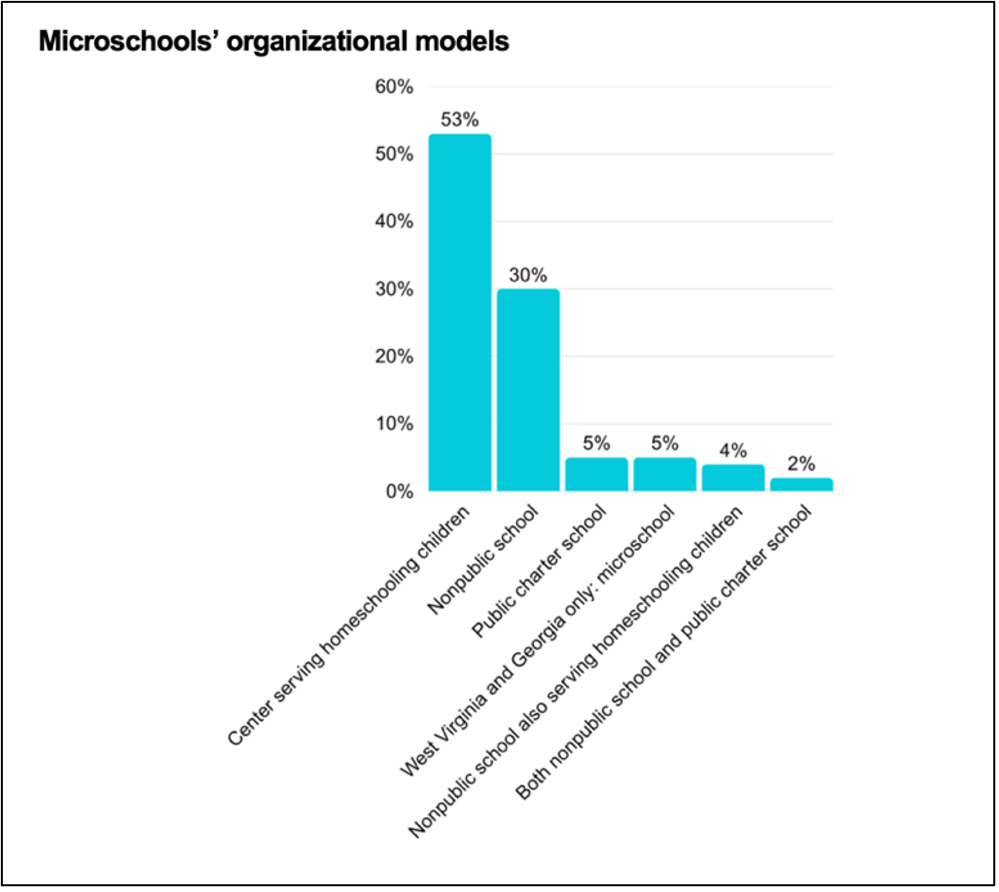

Soifer shared findings from his organization’s 2025 report, including survey data from 800 microschools in all 50 states and Washington, D.C.

Microschools are organized into a range of structures, the report found. The majority, 53%, operate as learning centers for homeschooling families. Another 30% are nonpublic schools, while 5% operate as public charter schools. A small percentage use overlapping models.

According to the report, the top three populations served by microschools are students who are neurodivergent, below grade level, or who have experienced emotional trauma.

Most microschools take a nontraditional approach to evaluating performance, using portfolios, observation-based reports, assessments, or other means. Just 29% give out regular letter grades, Soifer said.

In addition, microschools generally operate without accreditation: Only 22% of microschools in Soifer’s report were accredited.

What about charter schools? While parent demand is clearly driving growth, the policy underpinning charter schools “is still a smart reform,” Paisner said. Funding that follows a child to a charter school is automatic — “a critical lever for why charter schools can operate and continue to be efficient,” he said.

Other factors are also coalescing to foster an environment conducive to growth. Parents like that charter schools are public, Paisner said. In addition, the policy environment has become more favorable: The federal Charter Schools Program is funded at its highest level, and some states are focusing on deregulation of charters or additional avenues of support.

Last year, 104,000 additional students enrolled in charter schools nationwide, Paisner said. Over 3.7 million students now attend charter schools, according to the Alliance.

Weisberg shared information about trends in New York City (NYC) Public Schools.

The district has experienced very high demand for specialized high schools, he said, with around 40% of eighth graders taking the entrance exam for eight schools.

To address demand, NYC Public Schools created new innovative models, including career-focused high schools, an early college high school in the South Bronx, and schools designed to meet the needs of growing numbers of students diagnosed with learning disabilities, he said.

In addition, the district recently surveyed parents who left, finding they wanted more safety and rigor. Notably, those concepts “meant different things to different parents,” Weisberg said. Safety concerns could have involved a child’s commute home rather than worries about the school itself. Rigor included variables such as graduation and college matriculation rates, curriculum, and high-quality teachers and principals.

“This is what parents were looking for over and over again,” Weisberg said.

Districts have capacity to meet these needs, he added. “Rigor, safety, close to home… There is every opportunity to continue to provide those innovative models” within district systems.

Related reads

Growth in learner-centered models

Panelists also explored the expansion of learner-centered models, especially through microschools.

“Microschoolers have moved from being ignored to being acquired,” said Coi Marie Morefield, a partner for ecosystems at Education Reimagined.

Morefield founded the Lab School of Memphis in Tennessee with six students. Last year, her microschool served 75 students and was acquired by a charter and private school founder.

Tyler Thigpen, co-founder and head of The Forest School, a microschool in Fayetteville, Georgia, as well as the Institute for Self-Directed Learning, emphasized the importance of choice and agency. The goal of self-directed learning, he said, is to allow students to “struggle productively.”

Lizette Valles, who founded Ellemercito Learning Community in Downey, California, and launched the California Microschool Collective, shared her microschool’s emphasis on structured choice for students, who learn in a trauma-informed setting.

Sector expansion is coming, panelists said. Indiana is developing the nation’s first “public collaborative of self-directed microschools across that state,” Thigpen said. Through that system, microschools will operate as small, public charter schools with 20-75 students, organized through the Indiana Microschool Collaborative.

Ultimately, partnerships with schools or districts is necessary to scale learner-centered practices, Morefield said.

“Pure microschools, no matter how innovative, have natural growth limits,” she said.

Charter schools as engines of revitalization

Another panel highlighted ways in which charter schools are fueling economic and social development. “We’re trying to bring excellence to scale, we’re trying to… revitalize downtown,” said Brent Bushey, CEO of the nonprofit Fuel OKC, about his organization’s work to increase quality school options for Oklahoma City families. “And we’re also trying to spur innovation, all at the same time.”

Bushey highlighted the Crossroads Renewal Project, an ongoing effort to transform a downtown “dead mall space” into an education center with wraparound services. “It’s a community school on steroids,” he said.

“Today, we have 4,000 kids at the mall site going to school,” Bushey said. Students are from Santa Fe South Schools, a public charter school district, as well as Dove Public Charter Schools.

Danalyn Hypolite, senior director of leadership development at BES (build.excel.sustain) shared work to incubate innovative leaders and design schools reflective of community needs. BES fellow Kristy Beam, for instance, will launch the Academy for Innovation in Medicine (AIM) in Atlanta in 2026, in response to local need.

AIM will collaborate with Grady Health System to fill “an economic gap that exists in the community,” Hypolite said. AIM will be Georgia’s first STEMM (science, technology, engineering, mathematics, and medicine) charter school “to help address the state’s critical health care workforce shortage,” according to a news release from the Georgia Charter Schools Association.

Chris Neeley, superintendent of the South Carolina Public Charter School District, emphasized the creation of workforce centers of excellence in his state. As technical charter schools, they feature a curriculum “designed in partnership with business and industry,” Neeley said. “Charter schools actually end up being microeconomic and social engines of change and transformation.”

State policies supporting school choice

During the conference, a panel of Republican state lawmakers discussed policies enabling the expansion of new school models.

Oklahoma Rep. Chad Caldwell referenced a “fundamental contradiction” between policymakers’ desire for control versus the autonomy such systems need to flourish. This sets up a regulatory battle: Education providers need flexibility, and states want to ensure quality and accountability while protecting taxpayer dollars, he said.

Models that have struggled have been stifled by well-intentioned regulations, he said.

His message to policymakers: “Less is more.” States should remove statutes restricting growth and create a clear statutory authority.

Utah Rep. Nicholeen Peck advocated for trust-based education and, like Caldwell, a “less is more” approach to regulation.

“Do we trust the parents?” she asked. “I always tell people, ‘That child was born to you, not to the school.’”

Utah has a history of trusting parents, she said, and the state’s current homeschool requirements do not include testing, ongoing affidavits, portfolios, or background checks. Learning environments with 100 students or less can operate as a microschool or learning pod and are “completely open and free,” Peck noted.

Wisconsin Rep. Robert Wittke also offered advice for policymakers: Emphasize “survival and sustainability,” ensuring programs can withstand court battles, and visit different school formats to understand need and family struggles.

Florida Sen. Alexis Calatayud highlighted her state’s expansion of its Schools of Hope model, which incentivizes the highest-performing charter schools nationwide to come to Florida to serve the lowest performing-students, she said. Philosophically, the model hinges on “the investment of legislative dollars of state appropriation for high impact to low-income children,” she said. “To me, that’s the driver of why choice matters.”

Related reads

Accreditation and innovation

Another conference panel addressed accreditation, focusing on whether it blocks innovation or is a stamp of quality.

“I think of it as floors and ceilings,” said Christian Talbot, president of the accreditor Middle States Association of Colleges and Schools. One purpose is ensuring there is a “good, strong, high floor,” he said. “More importantly… it’s to raise the ceiling and move the walls out to enable innovation.”

“Accreditation matters, whether we like it or not,” he said, “because many state departments of education are now using it as the gatekeeper for school choice funding.”

Talbot outlined the four key stakeholder groups involved in accreditation as follows:

- Policymakers, who want oversight and fraud prevention.

- Families, who seek legitimacy and trust.

- Founders, who need flexibility and access.

- The public, which expects quality assurance.

The tension among these groups fuels friction that “typically slows innovation,” he said.

Walt Rogers, a former Iowa lawmaker and CEO of Inspired Life, characterized accreditation as a “bureaucratic solution to the question of accountability.”

The panel positioned Iowa as a salient example of how tension between stakeholders plays out around accreditation.

Iowa passed its ESA in 2023, Rogers said. Eligibility is universal — the ESA is available to any K-12 student in Iowa — but funds can only be used at accredited private schools.

This requirement impeded widespread implementation, said Raphael Gang, the director of K-12 education at Stand Together Trust, as 42 of Iowa’s 99 counties did not have an accredited private school. Moreover, the timeline to complete accreditation is a minimum of 12 to 18 months, he noted — after schools open.

“Legislators with good intentions of ensuring… this baseline floor of quality had essentially cut off access to the program for anybody new that wanted to launch a school in Iowa,” Gang said.

Panelists said that Iowa’s predicament helped fuel a new way forward, there and beyond.

Stand Together Trust “built a partnership” with Middle States and other accreditors, Gang said, to expedite the accreditation process in Iowa. Fourteen schools were accredited in six months.

This spring, Middle States created the Next Generation Accreditation process, designed, Talbot said, to be “faster, cheaper, nimbler.” Described in a recent Education Next article, the protocol is open to schools before they launch and takes just six months.

Rachel Good, the founder of Discovery Learners’ Academy in Chattanooga, Tennessee, shared her experience with Next Generation Accreditation. She launched the process in May and is set to be accredited in November, positioning her microschool to accept voucher and ESA funds next year.

While accreditation will benefit her by providing access to funding, validation, and documentation, she questioned its role as an important stamp of quality for parents.

“Largely, families that want really innovative (education) don’t care about accreditation because accreditation is a mark of standardization, to some level,” she said.

Philanthropy as a driver of reform

Two keynote conversations also addressed the role of philanthropy in school reform. Jeff and Janine Yass, who founded the Yass Prize to reward education innovation, discussed the prize’s origins and the future of school choice.

The Yasses “have contributed nearly $50 million to advancing educational innovation and reform,” Peterson said as he introduced them.

The prize, Janine Yass said, came together during the pandemic, as she and her husband sought to invest in schools showcasing four key elements, represented by the STOP acronym: sustainable, transformational, outstanding, and permissionless education.

Previous awardees have included over 200 public and private education models. On Oct. 10, prize organizers announced 23 contenders for the next Yass Prize.

During the keynote, the Yasses also shared their views on the current K-12 landscape. The best way to drive transformation, Jeff Yass said, is for states and lawmakers to shift the funding structure.

“They should be fighting as hard as they can to have the money follow the child,” he said, citing the increase in ESAs nationwide.

The Yasses also expressed confidence that emerging models could be scaled. “We need the ideas, and we need the entrepreneurs who take it to a brand new level,” Jeff Yass said.

“The microschools and the personalized learning is how kids want to learn, and they do much better with that,” Janine Yass added.

Ultimately, demand is the best barometer of success, Jeff Yass said. “If there’s a waiting list, then that school is working.”

In California, philanthropist Melanie Lundquist is pursuing a different path: leveraging private dollars to fuel public district transformation. The Partnership she co-founded has invested over $110 million in Los Angeles public schools since its inception, according to the organization’s website.

LAUSD Superintendent Alberto Carvalho joined Lundquist for a conversation detailing their work together to drive improvement in the nation’s second largest school district.

Currently, the Partnership includes 20 district schools that function as an incubation lab and represent the “highest need in every way, shape, and form,” Lundquist said.

“This giant lab is all paid for by philanthropic dollars,” representing $850 per student annually, Lundquist added. “It’s the impact over the entire district that we were going for.”

Such collaboration has enabled strategic, quick pivots.

“The Partnership is a swift boat that informs the best way forward for a much larger entity,” Carvalho said. “Philanthropic investment leads to additional flexibilities within this small subgroup of schools. Those flexibilities lead to incredible innovation and practices that then are analyzed, researched, and to the extent they are successful, they are scaled up.”

Mathematics in particular was the district’s “Achilles’ heel,” Carvalho said. Partnership schools were the first to try Illustrative Mathematics, later implemented districtwide.

“We saw as a result of a very coherent approach towards the teaching of mathematics explosive growth in performance,” he said.

An Oct. 9 news release following the conference reported “record-high” performance in math, reading, and science, noting, “LAUSD students not only surpassed 2024 results but also outperformed pre-pandemic levels from 2018-19.”

Lundquist and Carvalho are convinced their model is replicable. LAUSD is “a proof point,” Lundquist said. “We can do it there, we can do it anywhere.”

But sustained commitment is essential. “You’ve got to persevere,” Lundquist said. “I think that’s what’s really been missing with philanthropy in education.”

In the end, all-or-nothing debates about school choice are not fruitful, Carvalho said.

“The nation gets caught up in this ‘choice versus no choice,’” he said. “What I say is do whatever is right and good for kids… Let’s focus the argument on quality versus no quality.”

“Choice is a tsunami,” he added. “The only way to actually manage the current time of choice is get yourself a surfboard and ride the top.”

To view additional panel recordings, visit the Emerging School Models conference website.

Recommended reading