Haz clic aquí para leer este artículo en español.

Emily Francis remembers first wanting to be a teacher when she was still a little girl in Guatemala. She watched a well-dressed woman walk down the street with several kids walking behind her. The woman was a teacher, and the kids were her students.

“I want to have little kids following me. I want to dress nicely,” Emily remembers thinking. “I didn’t even know what it was to have a classroom or anything.”

All these years later as an ESL teacher at Concord High School in Concord, North Carolina, she has achieved that dream. The path wasn’t an easy one. But the journey gave her the skills she needed to be one of the most respected teachers in her district and in the state.

From Guatemala to the US: An education story

Francis loved school growing up. But she could only attend infrequently. As the oldest of five kids, in her culture, it was her job to help do everything around the house and even to work to help support the family. If she wasn’t home, she was at the market selling oranges. School wasn’t a priority.

“I would go some days, and some days I wouldn’t,” she said. “And because I missed so many days, they retained me quite a few times.”

And then her mom left the country, leaving her alone to care for her siblings for two years. It wasn’t until she was 15 years old that she left Guatemala for New York. At that point, her highest grade level was the sixth.

Even though she was so far behind, she was placed in high school when she arrived. She wasn’t fluent in English, but she was determined to succeed.

She went to school in Queens. Her grandmother enrolled her in a local community college to learn English, but she didn’t find the lessons very engaging. Nevertheless, she realized that if she didn’t speak the language, she wouldn’t be able to participate in class. And that was something she said she desperately wanted to do. So she took matters into her own hands.

“I had all kinds of dictionaries,” she said. “I remember going to the library and checking out different kinds of dictionaries and thesauruses. I would just sit down and copy everything that the teachers would write on the board. Go home and translate everything so I could have an idea of what the teacher was talking about.”

It worked. She placed out of English as a Second Language in a year and a half. And by the time high school was over, she had acquired the credits she needed to graduate. But in her senior year, she had to pass an American history exam in order to graduate. She failed the test in both English and Spanish. Her only option was to return the next year when the test was offered again.

“I just didn’t go back,” she said. “I was already 18. There was no reason to go back to school. I already had all my credits.”

Without a high school diploma, her options were limited. So she became a cashier.

The path to the classroom

Francis worked as a cashier for a while, but it didn’t pay enough. She applied to a number of different places, but nobody would hire her without a high school diploma. She said it was a disheartening experience.

“I didn’t feel I had the potential to do anything else but cashier,” she said.

Around this time, she became pregnant. She didn’t feel like New York was a good place to raise a child, so she decided to move down to Concord, North Carolina, where she had an aunt.

She hoped for a new start. But what she got was more of the same.

“I moved here. I tried to apply to different places to work, and everyone asked for a high school diploma,” she said.

She ended up working another cashier job at Bass Pro Shops, where she would work for three or four years and meet her husband.

Francis became increasingly frustrated with her professional opportunities. She wanted to do something different and leave the cashier life behind her. That’s when she found out about the GED.

“I was like, ‘What? Nobody ever told me that,’” she said. “Sadly, they should have told me that in high school … that’s what I do with my students.”

She enrolled in community college and completed her GED in six months. That was 2000. But still, she didn’t feel like she could achieve more. Not for four more years.

Emily Francis’ advice for teachers:

Be welcoming

“Make that [new] student feel like they belong in that classroom. I don’t care what level of literacy they have. I don’t care what level of English proficiency they have. I don’t care what country they come from. Make them feel like they belong in the classroom.”

Learn how language works

“Because I feel like if you learn how language acquisition works, you will have empathy.”

“You will have a student in the classroom who speaks the language at home and comes to school and speaks English.”

Keep on growing

“I don’t ever stop reading and learning. Just because I graduated back in 2013, I don’t stop. Growing is part of learning. And if I’m teaching students how to grow and learn, then I’ve got to do that myself, too.”

An immigrant’s higher education experience

In 2004, Francis began thinking about her future again. She said she realized that only education could give her more opportunities, so she enrolled in community college to get her associate degree.

At the same time, because she ultimately wanted to be a teacher, she applied to Cabarrus County Schools. Her expectations were meager. The application offered job choices that applicants could pick from. She chose custodian because she knew how to clean or serving food because she had done that for her siblings.

But there was a third choice: teacher assistant.

“Never in a million years,” she said. “That was my last choice just because I had to put something down.”

Before too long, she got a call from a principal. To her surprise, he wanted to talk to her about a teacher’s assistant job.

“I was so nervous,” she said. “I didn’t know what they were going to ask me.”

The principal and other interviewers began asking questions about reading and instruction in small groups. Francis tried to put the brakes on.

“I was like, ‘Whoa. First of all, did you see my application? I’m not even qualified to do this,’” she said.

She explained that really all she wanted to do was apply to be a custodian. But the interview continued, so Francis said she would just tell them her story.

She explained her childhood in Guatemala. She told the interviewers that she had taken care of four children after her mother left the country. The principal told her that all they were asking her to do was take care of children.

“I said, ‘Well, I can do that,’” she said. “They noticed something in me that I hadn’t even noticed myself.”

She got the job and began working in the classroom. Meanwhile, she kept pursuing her associate degree. One of the requirements to be a teacher’s assistant was to get an associate degree within a certain period of time. It took her three years because she could only go to school part time, what with her child and her work taking up a lot of her attention.

And then she walked across a stage for the first time in the United States.

“It felt like, ‘Wow. I could do this. If I can get an associate degree, I can apply for university. I could probably be a teacher if I just push myself a little more,’” said Francis.

In 2007, she started registering for classes at the University of North Carolina at Charlotte. To get into the department of education, she had to pass a test called the Praxis. Another test, another roadblock.

“I took it six times, and I failed the test again and again and again,” she said. “Without this test, I couldn’t be admitted to the department of education to be the teacher I wanted to be.”

Undeterred, Francis marched into the guidance counselor’s office. They told her there was no way around it. She had to pass the test. Francis asked to speak to the boss.

She got an appointment, walked into the office, and explained that she had already walked out of one school — and she wasn’t going to do it again. She explained that English was her second language, and that when she goes to take a test, she panics. She said there had to be another option.

The man she met with said there was one possible other way. But it was circuitous, and it would take longer. He told her she could get an undergraduate degree in anything she wanted. And then she could come back as a graduate student in education. It would add two more years to her educational journey.

“I don’t care,” she said. “It’s OK. We can do that.”

Francis got her bachelor’s degree in Spanish. Then she came back and got her master’s in teaching. Her educational journey ended in 2013. In 2012, she got a certificate that allowed her to get a teaching license. And then she walked into her first classroom as a teacher.

Teaching in North Carolina

Francis began by teaching English as a Second Language in elementary school. She did that for years — from 2012 to 2017 — before she felt a different calling.

One summer, she was asked to teach a summer class for new immigrants coming into high school.

“I walk in the classroom, and I say, ‘How are you? I’m Emily Francis,’” she said. “And they’re just staring at me like a deer in headlights. They had no idea what I’m saying. And it just hit me. These are the kids I need to be working with.”

Immigrant elementary students have a lot of time to catch up, Francis said. But high school immigrants have to do well in school while learning English — just like she did. She realized she could put her experience to work.

Francis said it’s her personal experience that gives her the motivation to do what needs to be done with students.

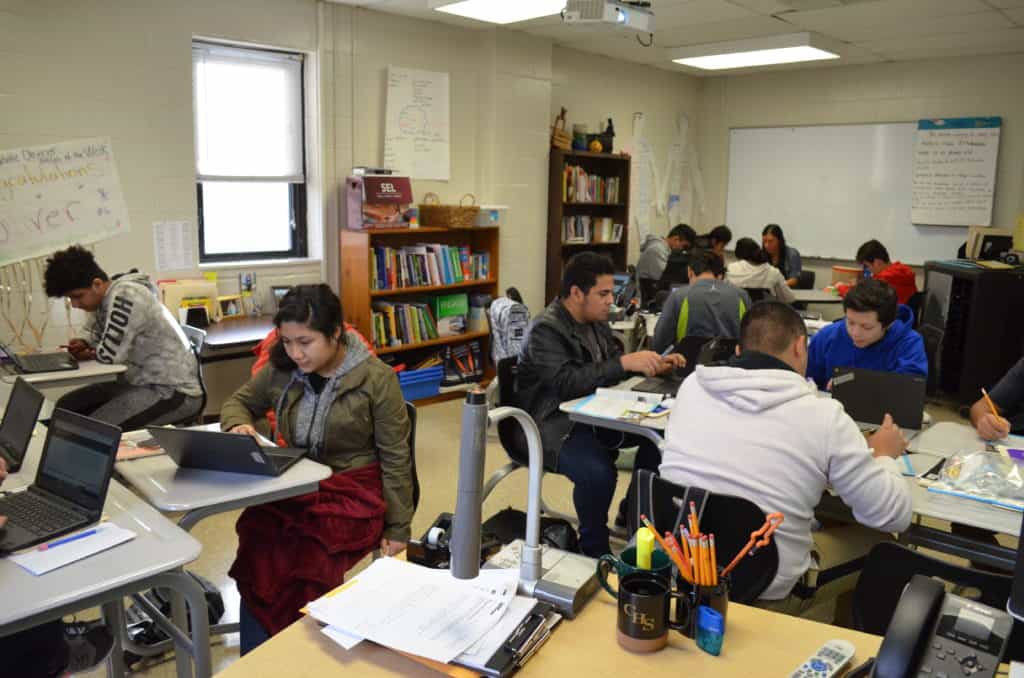

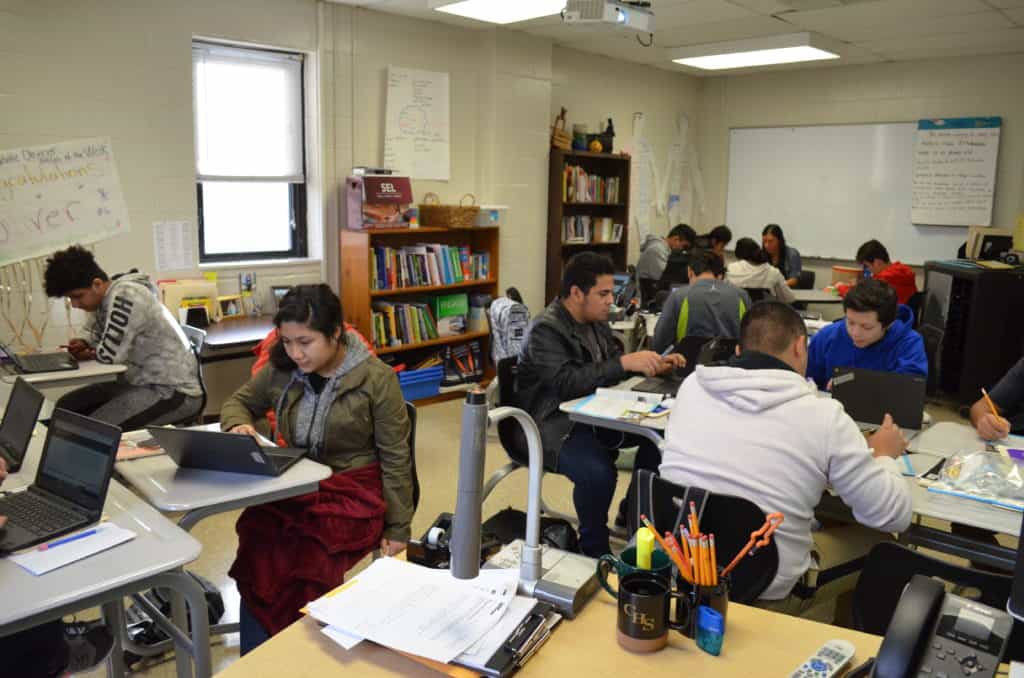

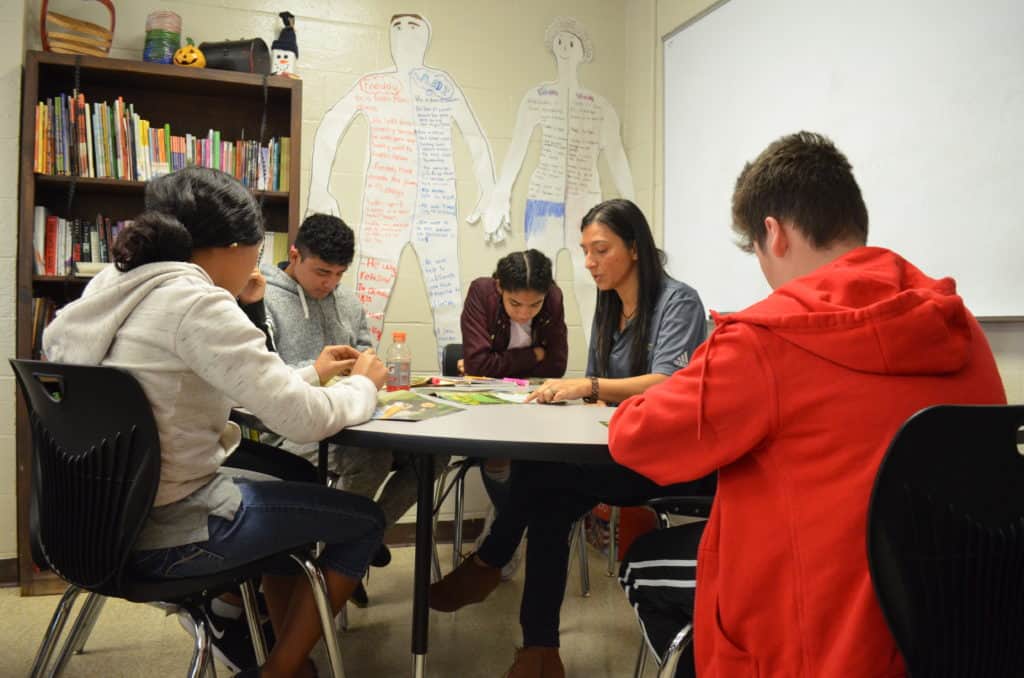

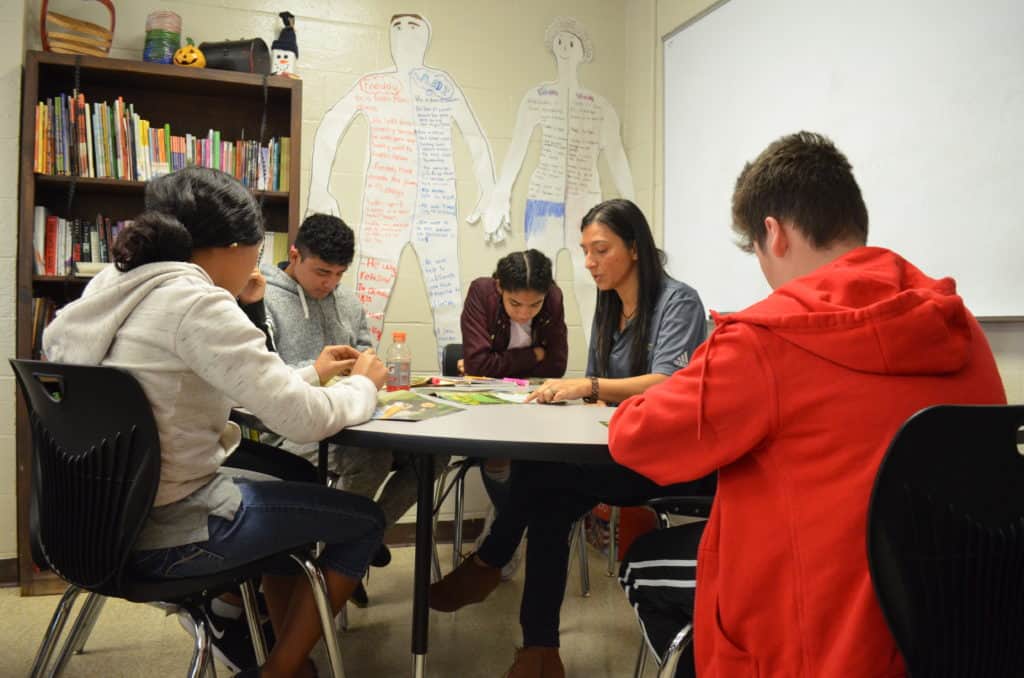

Sitting in her classroom, one can see how that experience translates into a personal connection. The students work on their ESL assignments. But they also work on homework from their other classes, periodically checking in with Francis to ask questions or seek advice.

The students chat with her in a way that is rare for students to interact with teachers.

“If I didn’t have my struggles and experiences, I wouldn’t be as effective as I am,” Francis said.

Adam Auerbach is the principal at Concord High School. He was an elementary principal at a school where Francis worked before he came to the high school. She was the district’s teacher of the year in 2016, which Auerbach said was a big deal. When he came to the high school, he had an ESL opening, but it was only part-time. He reached out to Francis, but she wasn’t interested.

When a full-time position opened up, Auerbach reached out to Francis again. After her experience during the high school summer class, she said yes.

“Hiring, to me, is one of the most important things we do,” he said. “At the end of the summer, we were like — that was probably the home run of the summer.”

The elementary school where Francis taught was a feeder school to the high school, so she would already know a lot of the families she would be working with.

Auerbach said that Francis’ effectiveness all comes down to her relationships with students and their families.

“Kids, whether it’s kindergarten or 12th grade, whether it’s math or PE, they’re only going to be highly successful if they have a good relationship,” he said. “That motivates them to learn what they need to learn, but also to take ownership for that learning.”

Effective teaching

In addition to her relationships with the community, Francis credits her time at UNC-Charlotte with helping her become an effective teacher. But her personal experience is what makes her uniquely suited to her role, she said.

In addition, she said her relationships with other staff are crucial, particularly since she came to high school from elementary school. She said she doesn’t know the content well enough at the high school level yet, so she can lean on other teachers for support, experience, and expertise.

“Having a relationship with teachers who do know the content allows me to better serve the students,” she said. “Having that communication with them and learning how is it that the content needs to be learned helps me with the language of learning for the students.”

Francis said another crucial tool to her effectiveness is understanding how the brain works. At UNC-Charlotte, she got a much better grasp of language acquisition and its peculiarities. It changed not only the way she teaches, but the way she parents.

“When I had my son, I never spoke to him in Spanish. I never allowed anyone in my family to speak in Spanish, because I didn’t want him to go to school speaking two languages and struggling like I did,” she said.

But after learning more about the science of language at the university, she changed her perspective.

“Oh my gosh,” she remembers thinking. “I’m hurting my child as opposed to helping him.”

Her second child is now in a Spanish immersion program.

This understanding filters down to her students. Francis knows that she isn’t going to expect an English language learner to be able to write an essay after having been in the United States for only six months. First they need to learn the words. Then they can learn how to write a sentence. Then they can move on to paragraphs, and eventually essays.

Emily has now been teaching ESL for eight years. She has been with Cabarrus County Schools for 16. For her, it’s a dream come true. For people like Auerbach, it’s a blessing.

“I’m just thankful everyday that she’s here,” he said. “The only bad side about Emily, because she’s so good and she’s so popular, everyone wants to see her. So I have to let her go different places and talk and inspire people.”