Editor’s note: This article mentions addiction, self-harm, and other mental health challenges.

The circle forms at 8:05 a.m. on the second floor of Memorial United Methodist Church in Charlotte. Twenty-seven teenagers shuffle into the hallway. This is morning check-in at Emerald School of Excellence, and the question comes the same way every morning: How are you really doing today?

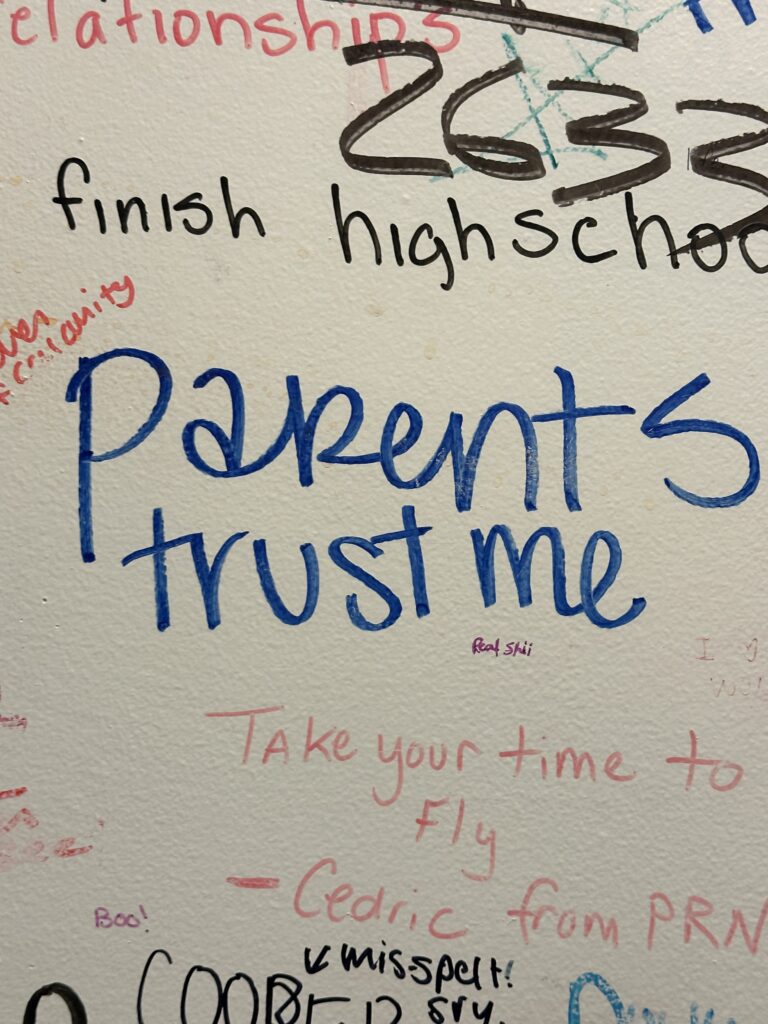

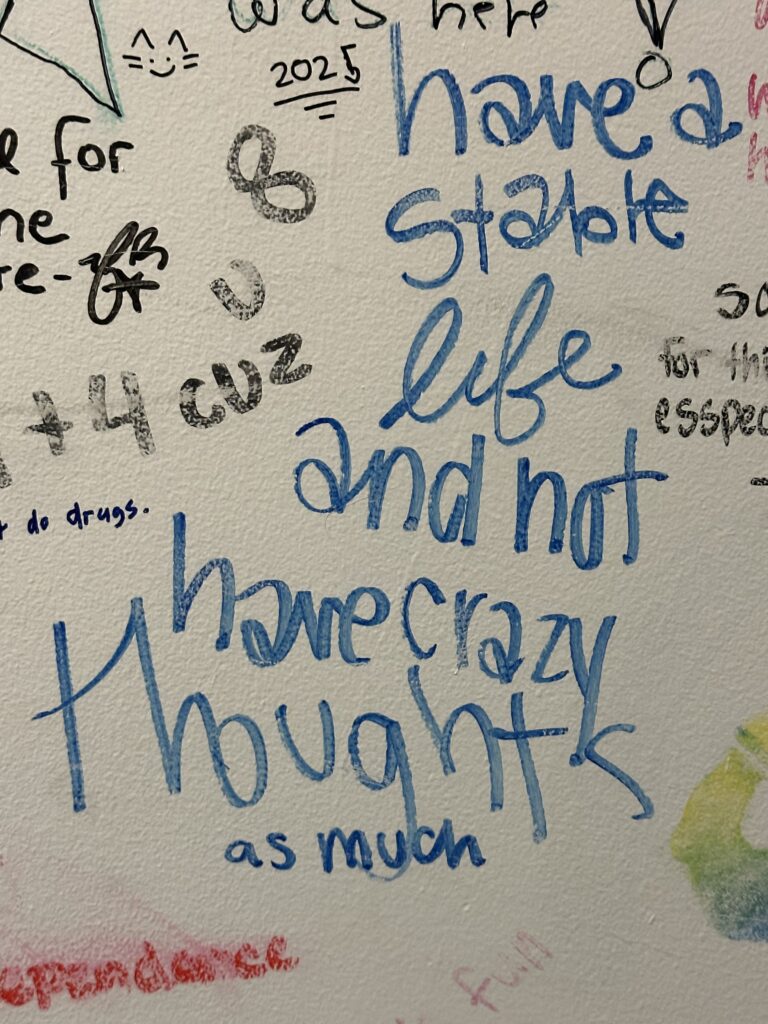

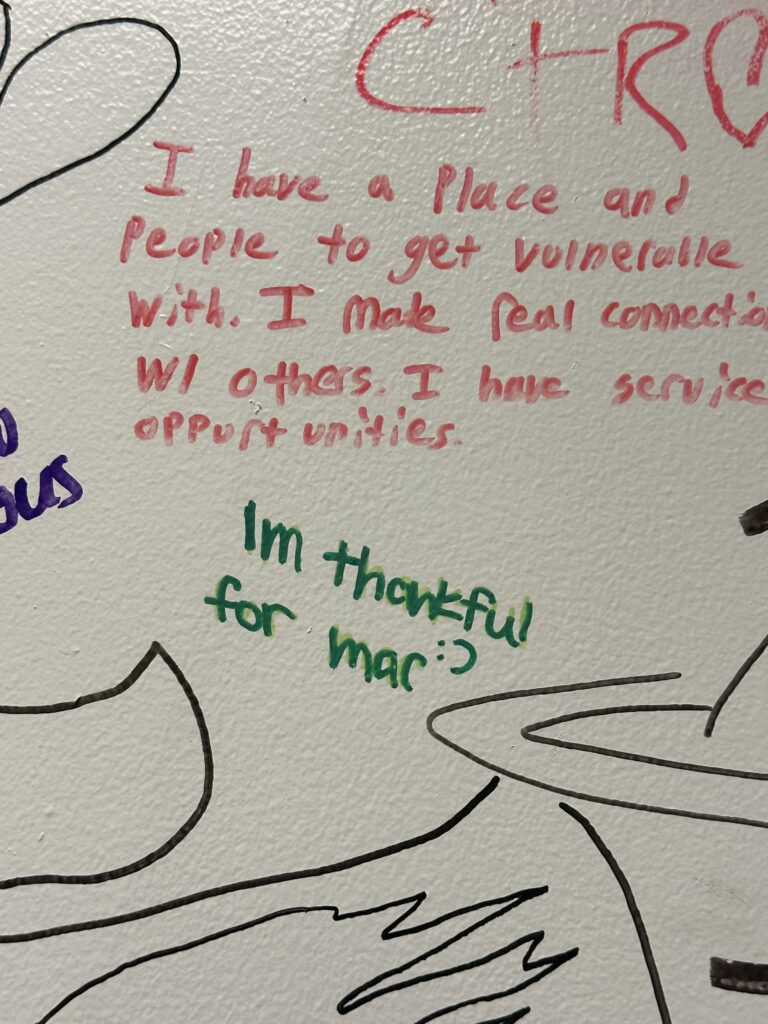

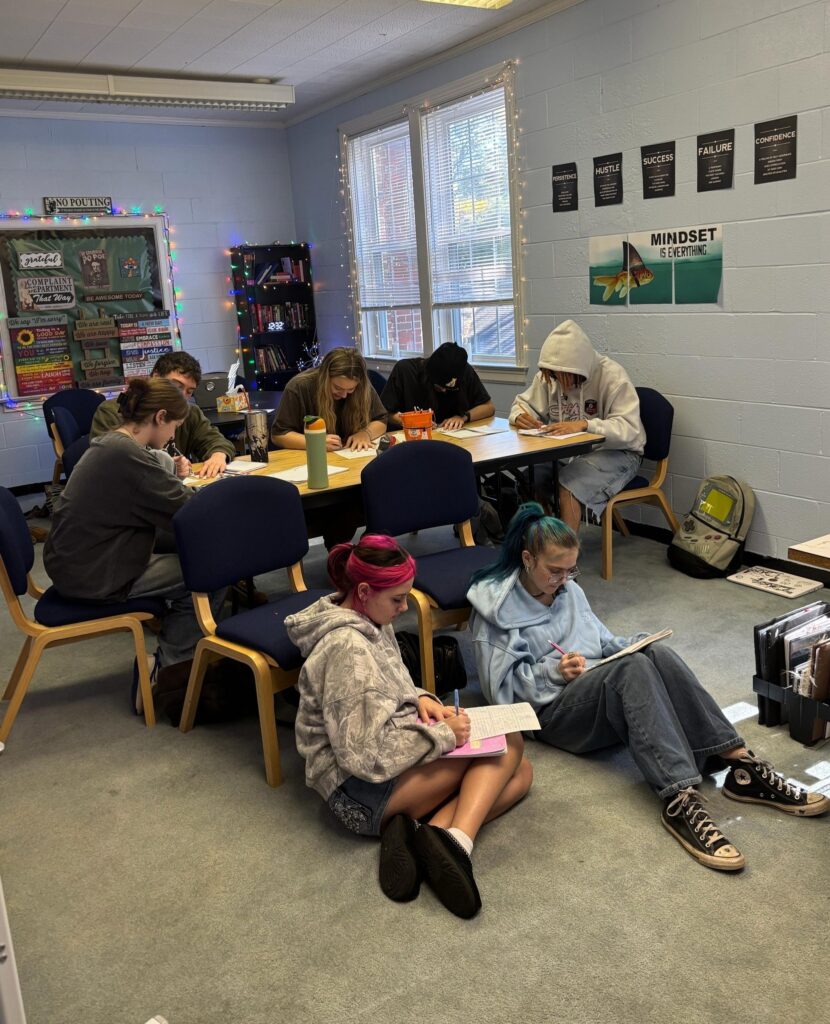

The answers come honestly. Someone is struggling with family drama. Another is celebrating three months clean. Nobody laughs. Nobody rolls their eyes. They listen. For many, this is the first school where they’ve ever felt truly seen.

![]() Sign up for the EdDaily to start each weekday with the top education news.

Sign up for the EdDaily to start each weekday with the top education news.

Every person in this circle battles addiction or mental health challenges. Every one understands that setting matters — that you can’t heal where you got sick.

That’s Emerald’s mission: to provide a quality education in a recovery-friendly environment to teens with substance use and mental health challenges.

The numbers suggest the mission works: 64% of students remained sober all year. Since 2019, 52% of students achieved one year or more of continuous sobriety. Some research shows that 30% of recovery high school students return to use six months to a year after treatment, compared to 70% among students who return back to their communities after typical treatment.

When a church said yes

Emerald School opened in fall 2019 with two students, one teacher, and a founder who refused to believe treatment had to end where school began.

The private school’s founder, Mary Ferreri, had spent two years screening a documentary called Generation Found — at movie theaters, an IKEA shopping center, anywhere she could gather people — trying to help them understand what a recovery high school even was. North Carolina had never had one.

After one screening, a woman asked: What do you need? “A location,” Ferreri said. That conversation led to Memorial United Methodist Church in east Charlotte, where, after presentations to church leaders, the church said yes.

“This is a great way for us to actually be the hands and feet of the church,” Ferreri remembers them saying.

Emerald School moved into the second floor. A preschool filled the rooms below — younger children starting their educational journey downstairs, and older students upstairs working toward better futures.

Ferreri had her own reasons for understanding what these students needed. During high school, she battled eating disorders, depression, and self-harm. Then she watched her adopted brother struggle with addiction for 20 years.

“My family still lives in it,” she says. “It keeps it so relevant and raw for me.”

‘Emerald was right there’

Layton Croft’s son was student number two — a 15-year-old sophomore who’d lost a year of education to addiction.

“We took a big chance because it didn’t feel like a school, it didn’t look like a school, nothing about it felt normal,” Croft recalls. “But we had enough comfort that everyone involved was capable and everyone wanted this to succeed. And it would never succeed unless someone decided to be the first students. So we did it.”

His son was cautious at first, bargaining for one semester with the option to bail. But he didn’t bail. He stayed. Three years later, he graduated on time, having made up the year he’d lost.

“He’s been sober ever since the summer of 2019,” Croft says. “He’s now a senior at the Berklee College of Music in Boston — a very difficult school to get into — and he’s doing really really well.”

Croft is clear that recovery began with his son’s decision. “His journey with substance abuse was relatively shorter than most, but it was incredibly aggressive and was not going to end well. He recognized that enough to say, ‘I need help.’ And thank goodness Emerald was right there.”

Croft, who holds a master’s degree in education, says Emerald School is different.

“I have never seen an educational institution focus on the whole person more than Emerald,” he says. “Most schools focus on the intellectual and physical. This one is literally 360 degrees wrapped around these young people — emotional, spiritual, intellectual, physical.”

School runs 8:05 a.m. to 2:25 p.m., bookended by morning check-in and afternoon checkout. Classes are tiny, with three to eight students. Afternoon electives can include music, art, fitness and time for journaling or peer support. The day ends with something light: a card game, “Name That Tune,” or “Minute to Win It.”

“We try to send them out with something that puts a smile on their face,” Ferreri says. “It gives us a safety net to catch when a student is struggling.”

Students complete all requirements for a full high school diploma. Graduates from the school have gone on to attend UNC-Chapel Hill, NC State, Clemson, Berklee, and community colleges, among other schools, or have entered the workforce.

A place for families

For Croft, Emerald School’s impact extends far beyond his son’s story.

“Addiction is a family disease, full stop,” he says. “If one member is struggling, everyone is affected — and in some ways, infected. One message I share in parent support groups is: Your biggest job is to focus on your own journey, your own recovery, and stop obsessing over your child. Emerald understands that. It’s a place for young people, but it’s also a place for families.”

Emerald has graduated about 50 students and hosts two alumni events yearly. At the most recent gathering, every graduating class was represented. Former students drop by when they’re struggling because they know where to go.

“They know who they can call,” Ferreri says. “They know how to get support. That’s what I want — that they never feel like they’re doing this alone. We’re a family.”

A model for North Carolina

Emerald’s success has drawn state support, including $1.2 million in the 2023 state budget. That investment allowed the school to diversify and offer assistance, school leaders said. The school also receives $14,236 in Opportunity Scholarships also called vouchers.

Today, 70% of students receive other financial aid.

Ferreri, who serves on the national board of the Association of Recovery Schools, hopes Emerald can serve as a blueprint for other communities.

“It’s not about Emerald becoming an 800-student school,” Croft says. “I think that would actually be bad. We need 800 Emeralds all over the place. Mary saw that documentary and said, ‘I want to do that here.’ Now, if someone in Hillsborough or the Outer Banks learns about Emerald, they should do it, too. It’s not rocket science. It does require key ingredients, but we’ve proven you can get funding, accreditation, and community trust.”

Back in that upstairs hallway, end-of-day checkout winds down. A student laughs at a teacher’s joke. Another asks about a college application.

Students head out — some driving themselves, others catching rides — while families at home hope for the same thing: another day sober, another day learning, another day believing a different future is possible.

In a state where youth mental health challenges and addictions are rising, this little school in a church building on Central Avenue is proving something important. That when you wrap a young person in community, accountability, and love — and you refuse to choose between recovery and education — you don’t just save a school year. You might just save a life.

Recommended reading