Back in 2018, Ernst & Young led an operational assessment of the N.C. Department of Public Instruction (DPI). Recommendation six of 17 called for a redesign of the regional support structure “to better coordinate and differentiate identified supports” to school districts.

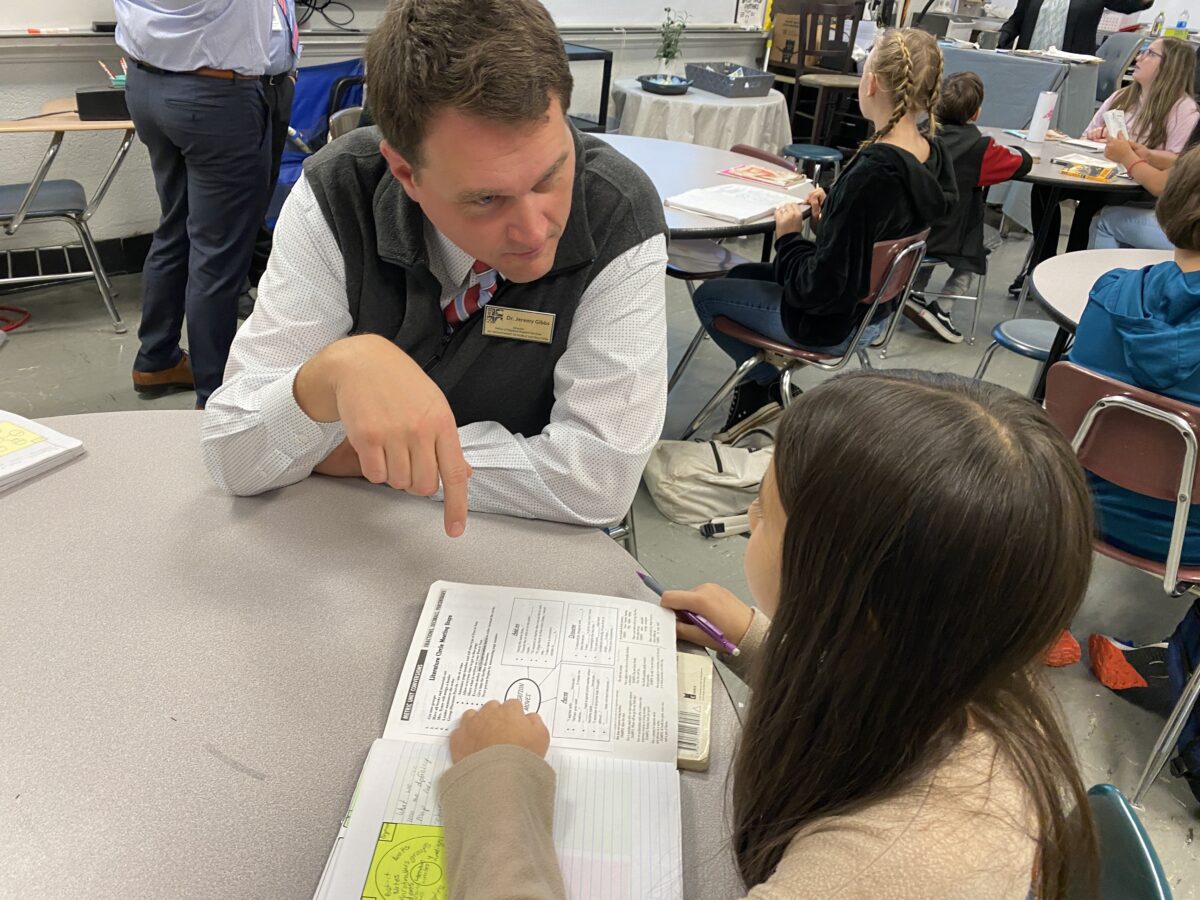

Dr. Jeremy Gibbs was among the regional directors hired. Gibbs grew up in Henderson County, and so the Western Region he now serves has always been home. A music teacher, he started his career in Pitt County. He moved into school leadership, first as an assistant principal in Wake County and then serving as a principal at Brevard High School in Transylvania County where he went on to work in the district offices as director of human resources and chief academic officer.

Looking back, I had no idea how important the work of DPI’s regional directors would become, and their importance was only heightened as COVID-19 ravaged the experience of education for our students and educators.

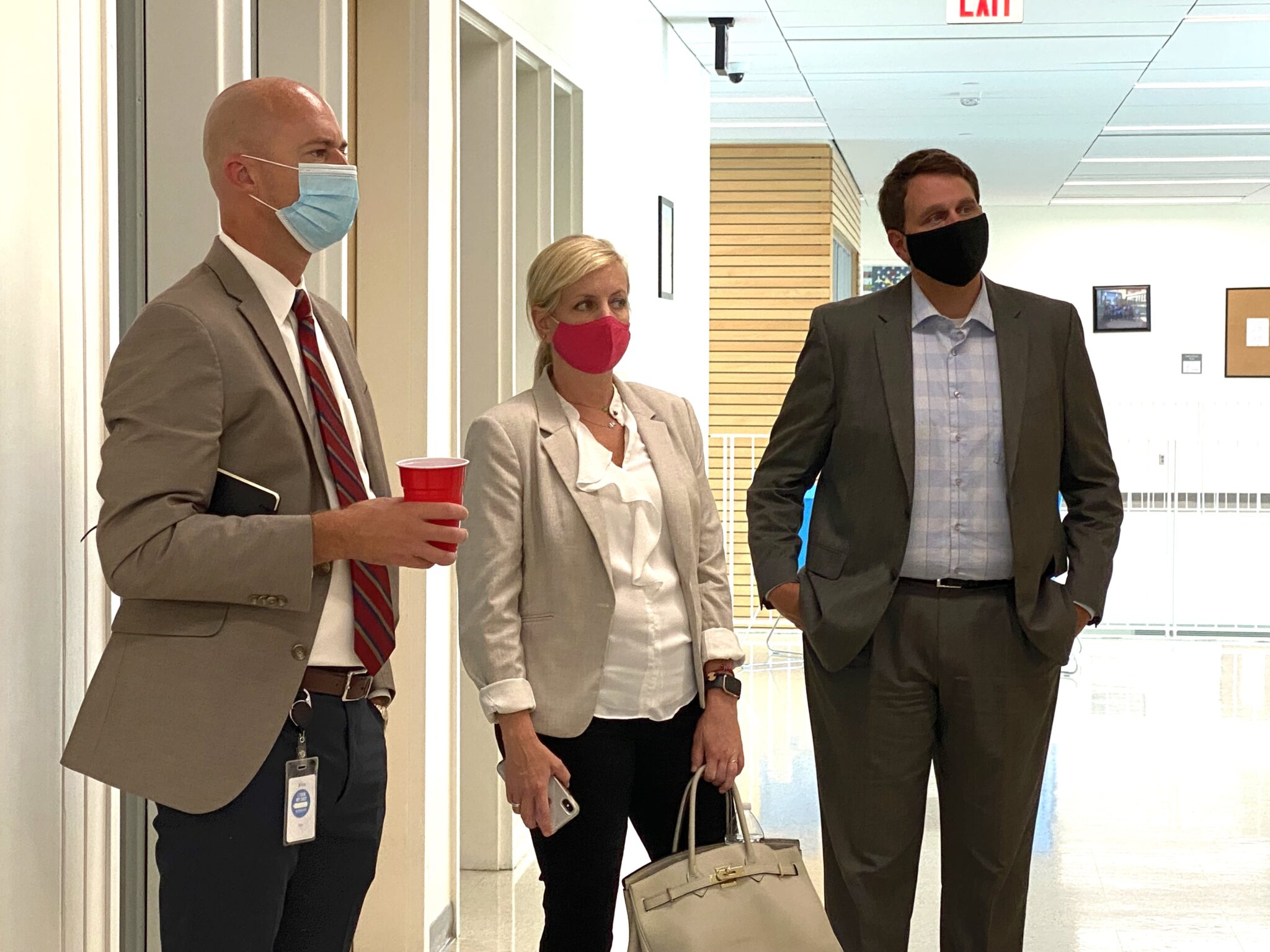

Over the course of two years, I have visited schools in 13 counties with Gibbs, studying leadership in the classrooms, in the schools, and in the districts before, during, and after the pandemic.

We often traveled together, and Gibbs also traveled with other members of the EdNC team. Sometimes there were leaders from DPI with us. And sometimes serendipity was involved, and we just happened to be in the same place at the same time. At this point, we have been to several districts multiple times together.

It has been my privilege to watch his leadership unfold.

It’s the kind of leadership that included driving a school bus during the 2021-22 school year each morning to help with driver shortages.

As our state’s district and regional support continues to evolve — read more about that here — the role of the regional directors and their relationship to regional support teams will matter not just for our schools designated as low performing but for all of the educators they support.

The eye of the hurricane

Our first district visit was scheduled for October 29, 2020, starting in Graham County. A hurricane was bearing down on western North Carolina, and as Freebird McKinney and I left Asheville at 6:32 a.m., I was just sure Gibbs would cancel. The rain was torrential, and the power was out.

When we arrived at the central offices of Graham County Schools, there he was, and it was clear from the reaction of Superintendent Angie Knight that this is precisely the kind of day when Gibbs shows up. We met with the leadership team in the dark, talking about everything from crisis management to district finances.

“I’ve been doing this way too long to have my feathers ruffled by a hurricane,” said Knight.

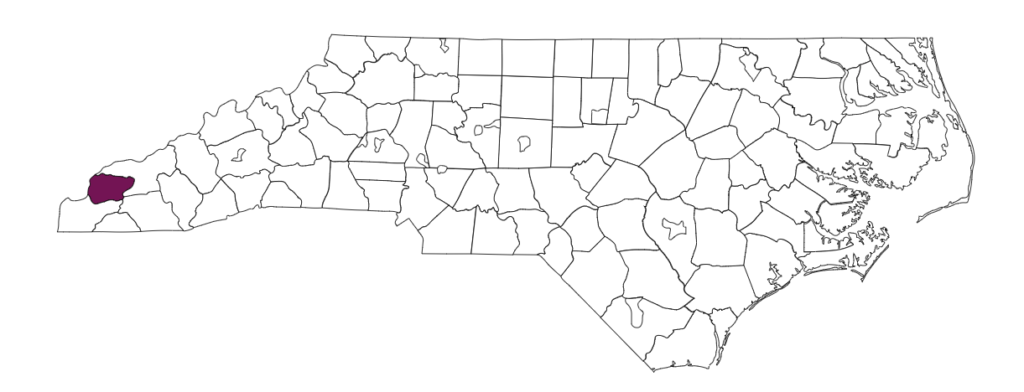

Graham County Schools is Gibbs’ only district identified as low performing. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the county has about 8,000 residents. The school district and county government are the largest employers, and yet just 13.5% of the residents have a bachelor’s degree compared with 33% across North Carolina.

Think about how that impacts the teacher pipeline. Knight calls the state’s TAs to Teachers program a “miracle,” saying “we’ve got to grow our own.”

The median income in the county is $41,977, almost $20,000 less than the statewide average. Knight told us that students have “a lot of needs before we get to academics.”

Lester Greene, the district’s finance officer, said, “the biggest issue is always funding,” and Knight added, “our buying power is reduced every year.”

“Our kids deserve every opportunity we can give them, and they don’t know sometimes how bad it is.

School needs to be their happy place. It needs to be their safe place.”

— Superintendent Angie Knight, Graham County Schools

“Jeremy’s offered to help me,” Knight said, even offering to help run payroll. “I know how to do it. I just don’t have time to do it.”

In small, perpetually under-resourced districts like this one, leadership is the real miracle — in the classroom, in the school, in the district, and in the community.

And the reality is that what Knight and other superintendents need most — especially on the worst days — is extra leadership capacity.

The role of regional director

Regional directors get a computer and a car, but their offices are the schools and districts they serve. Gibbs has visited 117 schools across his 16-county region and has put 75,000 miles on his car so far.

Part-time coach and part-time cheerleader, in this role Gibbs seeks to understand how different classrooms, schools, and districts work.

He sees which leaders can “make it work and get things done,” even in our hyperpolitical times. The most rewarding part of the job, he said, is seeing multiple perspectives and multiple approaches to education leadership.

Districts needed, he said, “someone who wasn’t in their problem with them,” someone who could stay focused on student growth and identify solutions. Often, he takes a problem in a district and goes and works on it for them because, he noted, “they have a lot going on.”

Regional directors, he said, serve as full-time bridge builders, connecting schools districts to DPI. With a customer service orientation, the directors serve as a point of contact for principals and superintendents — someone they know, they have a relationship with, who they see in person regularly.

From district superintendents to the state superintendent, Gibbs sees himself as “an equal opportunity giver of constructive feedback.”

That has helped in the building of relationships. “Those in the field feel like I advocate for them and that I serve as a helpful liaison in both directions,” he said. “I’m paid by the state, but I represent them.”

“To connect with the field,” Gibbs said, “you gotta go, you gotta do, you gotta experience, you gotta be there on the good days and the bad days so the people feel like you are in it with them, you understand what they are dealing with.”

Support for principals and superintendents

In March of the 2019-20 school year, the pandemic hit, which exacerbated all of the challenges schools and districts regularly encounter.

As schools started the new year in August 2021, many of us thought and hoped the worst of the pandemic was behind us. We were wrong.

Gibbs said the 2021-22 school year proved to be “the hardest thing we had ever faced.”

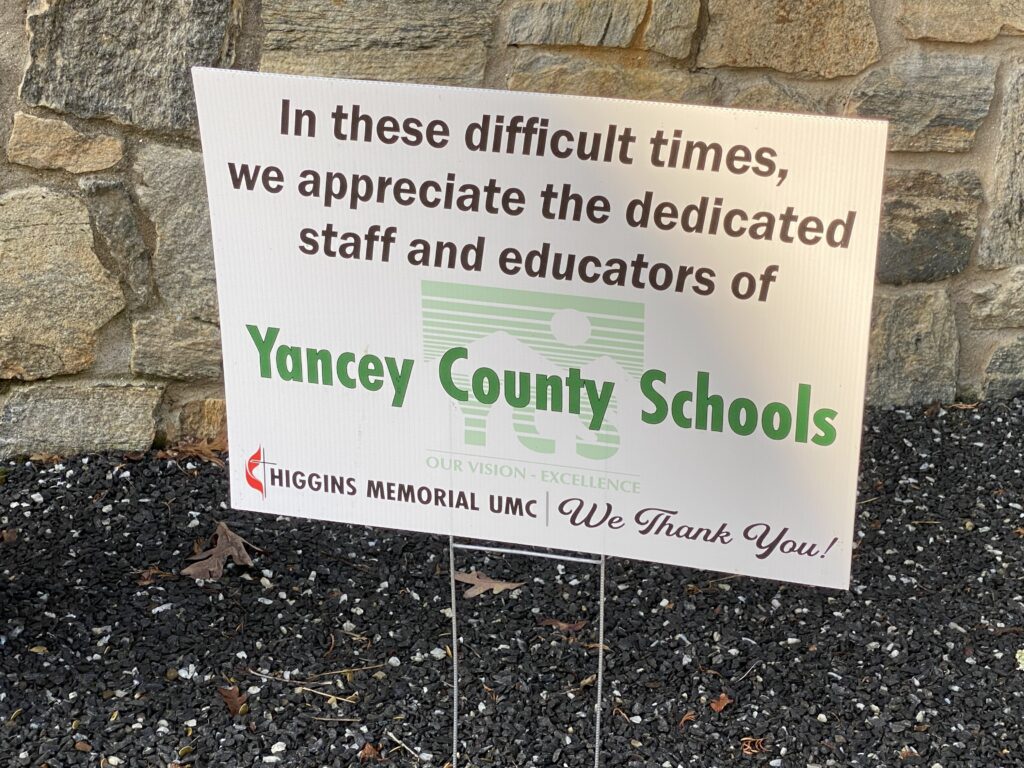

Superintendent Kathy Amos started her job as superintendent of Yancey County Schools on July 1, 2019. Due to retirements, Amos needed to build a pipeline for future principals in her district during the pandemic. Gibbs helped her start a leadership academy.

In Henderson County Public Schools, we met with then-Superintendent John Bryant to learn about the opportunity the pandemic presented to empower teachers and re-imagine learning. “As soon as we don’t have a script, professional educators do amazing things,” said Bryant.

Everywhere we traveled, we learned more about how schools and districts were using the unprecedented federal funding for COVID relief.

This was Superintendent Dana Ayers’ second day with students in Jackson County Public Schools. In anticipation of historic flooding, Gibbs was there to provide support, but he was also interested in talking about her desperate need for more pre-K classrooms and the K-8 curriculum she was investing in.

As the reports of flooding poured in, Gibbs made an unplanned stop at Rosman Middle and Rosman High School in Transylvania County Schools to check in with school leaders. They whipped out their cell phones to show him photos and videos of the day they survived.

Introducing NC’s Teachers of the Year to the region

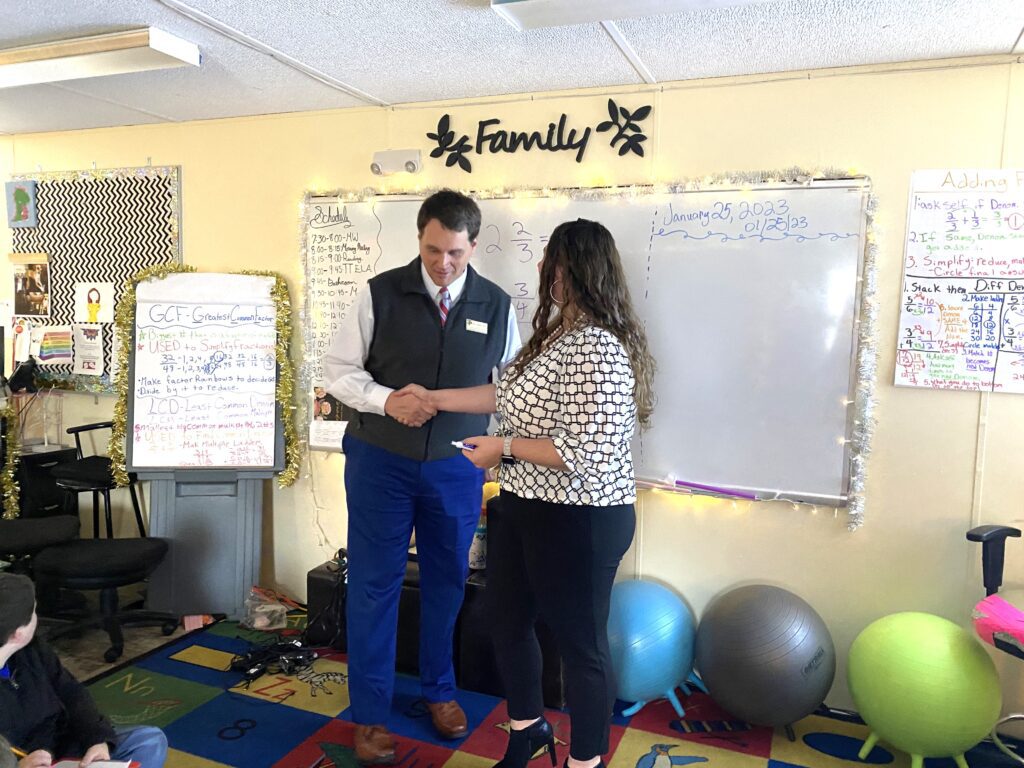

On September 18, 2022, Gibbs planned visits for Leah Carper, the 2022 Burroughs Wellcome Fund North Carolina Teacher of the Year, and Ryan Mitchell, the 2022 Burroughs Wellcome Fund Western North Carolina Teacher of the Year, to visit schools in four districts in one day.

Call it a rite of passage.

The visits were structured to include small group discussion with students, classroom observation, the opportunity to talk to educators, lunch with beginning teachers, and a bit of sightseeing along the way on the Little Tennessee River.

Connecting practice to policy

The experiences of regional directors, including Gibbs, informs the work of DPI and allows classroom and school practices to inform policy change.

It also allows the directors to work with school leaders to get buy in.

In his travels, Gibbs finds leaders.

Gibbs connects leaders.

Gibbs identifies promising practices for DPI’s clearinghouse.

On a recent trip, we visited Hot Springs Elementary in Madison County. We met teachers who drive an hour each way from Tennessee to teach in North Carolina. We talked to teachers whose classrooms did not meet growth because of particular student outliers, which requires a very different set of interventions.

At East Yancey Middle School, we met with this school improvement team to talk about why they outperform year after year, and when you get right down to it, it comes from intrinsic motivation and school culture and a lot of hard work.

Lisa Gahagan, assistant superintendent in Madison County Schools, said what she likes about Gibbs is that he is realistic, a straight shooter. She said Gibbs can disaggregate and translate data, and he doesn’t just suggest interventions but helps to think about how to implement them, often going class by class.

She wondered out loud, “what if you didn’t have someone who would be real with you?”

Promising practices in Western NC

Regional focus, statewide leadership

One week, I ran into Gibbs when he was speaking to the Cherokee County Schools Board of Education. Then-Superintendent Jeana Conley introduced Gibbs, saying “he has his thumb on a lot of what’s going on in Western North Carolina.” He shared what he was seeing in other districts with the board about student nutrition, remote learning, and social-emotional support early in the pandemic.

Other weeks you can find Gibbs in Raleigh attend a meeting of the N.C. State Board of Education. Recently, he supported DPI’s Accountability Working Group.

EdNC’s Rupen Fofaria has attended DPI’s AIM Conference the past two years.

He writes, “At AIM, Gibbs moved around the Raleigh Convention Center with purpose. He pointed district leaders in the direction of sessions relevant to challenges they’d shared with him in the past. He connected his constituency with state-level leaders and resources. And, over multiple sessions across multiple days, he guided attendees from his region through group exercises intended to both help them process the vast information they received at the conference and build or improve their district strategic plans.”

You can also find Gibbs serving as vice chair of the Board of Trustees of Blue Ridge Community College (BRCC) and on the SECU Advisory Board in Transylvania County.

Laura Leatherwood, president of BRCC, said, “His presence and service on our board has been invaluable over the last nine years. He brings a deep knowledge of K-12 education and is able to help us connect the dots to our community college programs and operations. We are so incredibly grateful for his leadership in Western North Carolina.”

“His contributions to our institution will have a lasting impact on the families of our communities and region for years to come.”

— President Laura Leatherwood, Blue Ridge Community College

The mayor of the west

Julie Pittman, the 2018 Burroughs Wellcome Fund Western North Carolina Teacher of the Year and now special assistant on educator engagement to the state superintendent, has worked alongside Gibbs in every district he serves.

“He has a depth of knowledge of the history and system of education, and an entirely unique ability to build relationships with every single person he meets,” said Pittman, describing Gibbs as dedicated, funny, and astute.

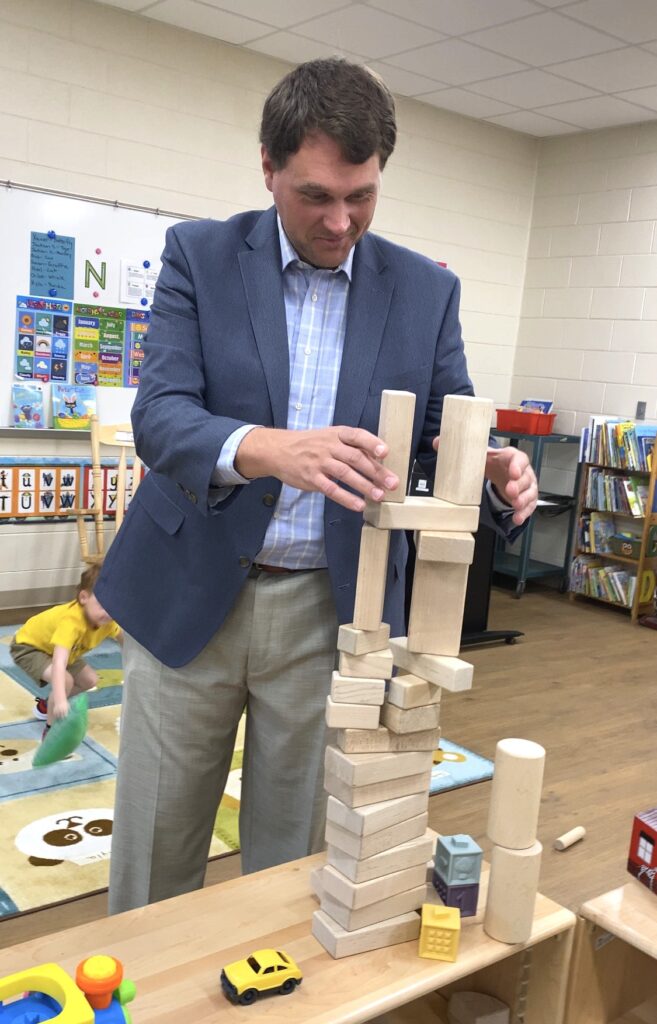

After describing how he can move from counseling a superintendent in one instant to building a block tower with a preschooler in the next, she said, “our region has a different culture than the others, and Jeremy knows all the data and all the stories.”

Pittman said, “He really is like the mayor of the west!”

The regional directors

There are eight regional directors across North Carolina.

Stephanie Dischiavi leads support services for the northwest region. Prior to joining DPI in January 2019, Dischiavi served 20 years as a teacher and principal in Hickory Public Schools.

Dr. Heather Mullins leads support services for the southwest region. Prior to joining DPI, Mullins served as the chief academic officer for Newton-Conover City Schools.

The Piedmont Triad region does not have a regional director at the moment.

Dr. Kendra King leads support services for the Sandhills region. Most recently she served as the executive director of student services for Wilson County Schools.

Melany Paden leads support services for the north central region. Prior to joining DPI in January 2019, she served for nearly five years in different positions at the department. Paden has served in the education field for over 20 years in the public and private sector as a principal, director, education innovation specialist, coach, and teacher in North Carolina, New Jersey, and South Carolina.

Dr. Beth Metcalf leads support services for the southeast region. Metcalf has served North Carolina public schools’ student and families for 23 years. Prior to joining DPI, she served as the executive director in the instructional services department in Pender County Schools.

Dr. Catherine Stickney leads support services for the northeast region. She brings 30 years of experience in education to this role. Prior to her role with DPI, Stickney served as the superintendent of Northbridge Public Schools in Whitinsville, Massachusetts.

Our thanks to all of you for your leadership and public service.

P.S.

When you are on the road in a pandemic and the worst weather seems to accompany you, well, stuff happens.

On this day, Gibbs had to detour us down through South Carolina to get us back to North Carolina safely. It was truly above and beyond.

On another day, I am pretty sure he saved my life when a herd of deer bounded right in front of us.

One final fun fact, on the weekends you can find the Gibbs family in their very own modified school bus camping around the region he loves and serves.

Recommended reading