|

|

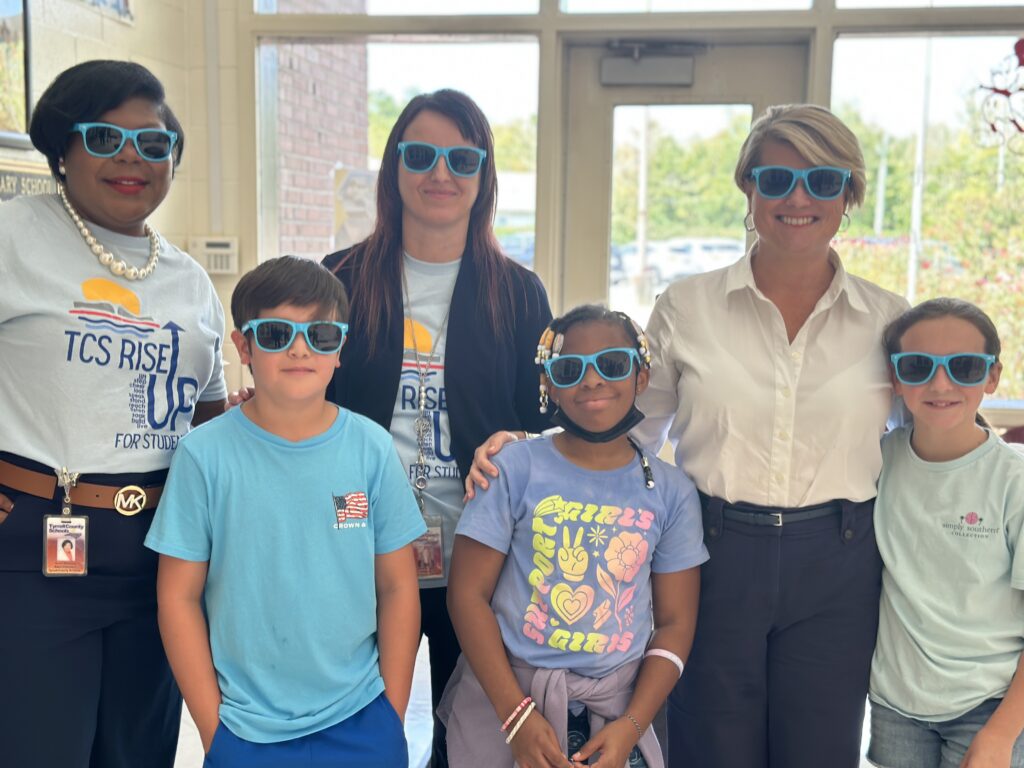

Mary Bridgers stands before a sea of students, teachers, staff, and community leaders in the parking lot at Tyrrell Elementary School in Columbia. The school’s principal, in her first year at the helm there, is pepping up the students for a celebration.

The kids and their teachers are decked out in blue. State Superintendent of Public Instruction Catherine Truitt is on hand, donning blue sunglasses. The district’s superintendent, also in her first full year on the job, is wearing a blue shirt that reads, “TCS: Rise Up for Students.” Two members of the school board, the chair of the county commissioners, and several community partners dot the crowd.

The students are holding their excitement in, but they have one pressing question.

“What are we even doing here?” one little girl finally asks.

The answer: Throwing a blue party. Blue is the color indicated on the state accountability report when a school exceeds growth expectations. Tyrrell Elementary did that last year — while the two other schools in the district met expectations. Every subgroup in the district met expectations (or better), and the district as a whole came off the state’s low-performing list. The elementary school celebrated a 20% increase in its proficiency scores.

“You’re here because we did something amazing,” Bridgers says.

There’s momentum behind the turnaround efforts here – a credit, district and county leaders say, to both district leadership and the Department of Public Instruction’s (DPI) CARES team.

“Ensuring that you all are positioned for success requires an all-hands-on-deck approach,” Truitt tells the students. “It’s so clear to me that in the case of this district — (Tyrrell County Schools) — you have done that.”

Student-centered behaviors

Four superintendents, including two interims, led Tyrrell County Schools (TCS) between 2015 and the school board’s selection of Karen Roseboro last October. During that time, the district’s schools struggled with the state’s accountability standards — labeled as low-performing, with all three receiving either a D or F performance grade and failing to meet growth expectations.

Educators were trying, but focus strayed under the inconsistent leadership. Without a stable, unifying vision, educators were doing what seemed best from their individual perspectives, Roseboro said.

“Adult behaviors impact student outcomes,” she said as she walked the elementary school halls before the celebration. “We’ve been adult-centered for quite some time, and now we’re getting back to: Who’s the client? Who’s the customer? We’re going to do what’s best for them. And we’re willing to get in the trenches with our teachers.”

Roseboro is a turnaround specialist from Winston-Salem/Forsyth County Schools. She spent six years on that district’s leadership team, five as superintendent of school turnaround. When she arrived in Tyrrell, on the heels of pandemic-interrupted years, the district had lost several kids to other options, she said – including home schooling and a nearby charter.

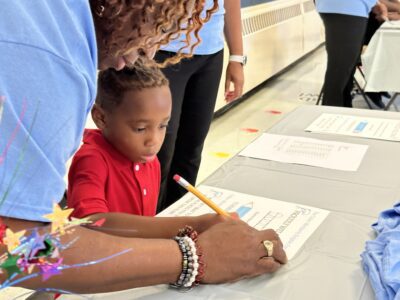

Now, with class sizes below the state average at the elementary school, she says teachers are finding one-on-one time with students. They’re getting to know the kids – what they like and don’t like – and they’re delivering instruction designed for each particular child.

“It’s a constant fluidity to that,” Bridgers said. “Just because you’re receiving interventions this month doesn’t mean you’ll be in there next month. You may be rocking and rolling with what we’re doing next. So we’re constantly touching those students based on their needs.”

Roseboro added: “That personability factor, I think, is what’s the selling point right now. It’s how we’re going to reclaim those kids that we lost out of the district.”

Teacher-empowering design

The district is empowering and supporting teachers to achieve that ultimate focus on students. Among Roseboro’s initiatives is finding advanced teaching roles for high-flying teachers. It’s called a teacher’s academy and looks a lot like the state’s advanced teaching roles (ATR) program.

“We needed to do that here because we had so many veteran teachers who had been leading,” she said.

Roseboro had written the grant for Winston-Salem/Forsyth County Schools to get state ATR funding after helping to launch a teacher academy there. She looked into getting a grant for Tyrrell, but opted to stick with a grassroots version because she wanted to maintain a grasp over all the changes happening in the district.

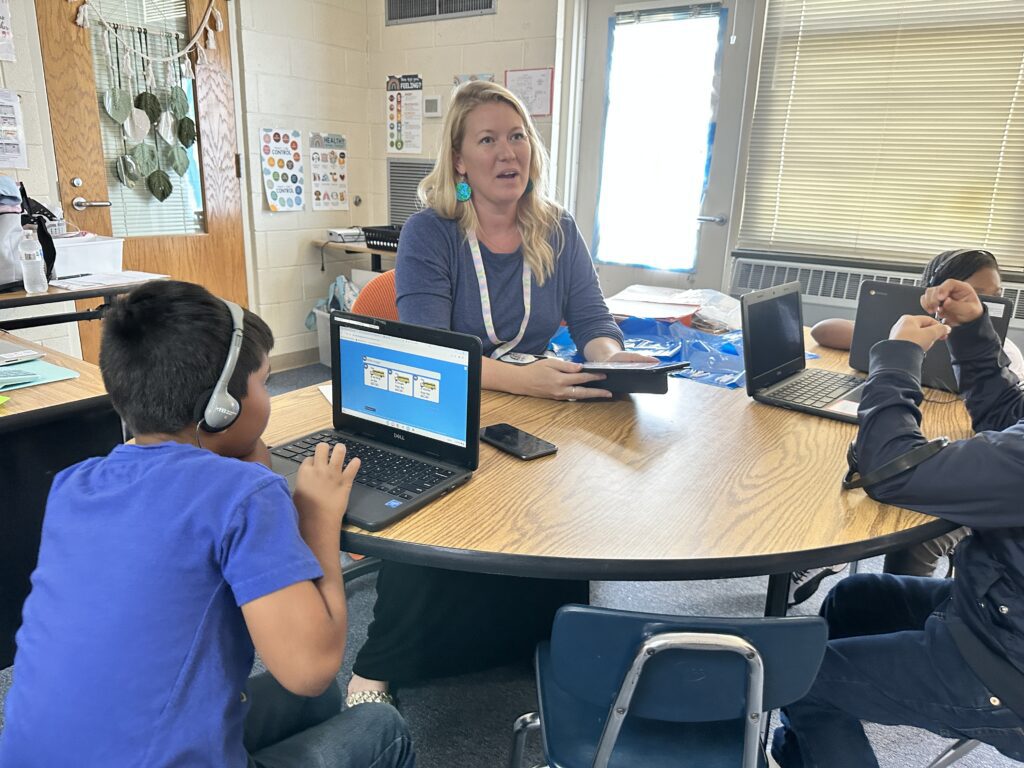

She said the grassroots version, implemented two months after she started her job, has served the district well. Teachers get a pay bump through both federal dollars and the state’s local supplement fund. They get leadership opportunities — as AIG, early learning/pre-K, MTSS, and data collaborator leaders, for example. Teacher leaders also serve students in additional capacities, including tutoring.

And teachers see that central office and school building leaders are in their corner, Bridgers said.

“That’s the biggest thing,” Bridgers said, “is the teachers and staff knowing that you’re invested and that you’re knowledgeable — and, if you’re not, you’re willing to learn alongside them.”

Roseboro also instituted a more open-door policy at the central office. Many of the district’s teachers had never been to the office. Now, the district hosts frequent professional development opportunities there.

Teachers seem to be responding.

“I’ll tell you there was just a piece that was missing for me and I wasn’t sure what it was, and I thought, ‘I need to think outside the box a little bit,’” said elementary teacher Shannon Moore, who came to the district this year from Dare County and drives nearly an hour from Manteo to get to work.

“I found this little, small school. I didn’t know a whole lot about Tyrrell, and I came out here to interview. I interviewed with five of the staff members and everything clicked. They said what I needed to hear. I needed a small school where everybody was very close and works very close together. I was really missing that relationship piece.”

Literacy gains and early literacy specialist

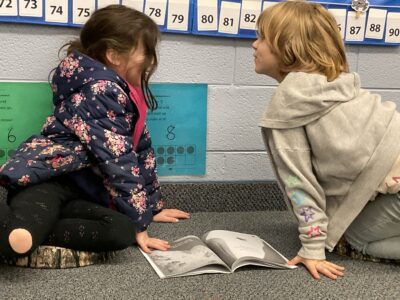

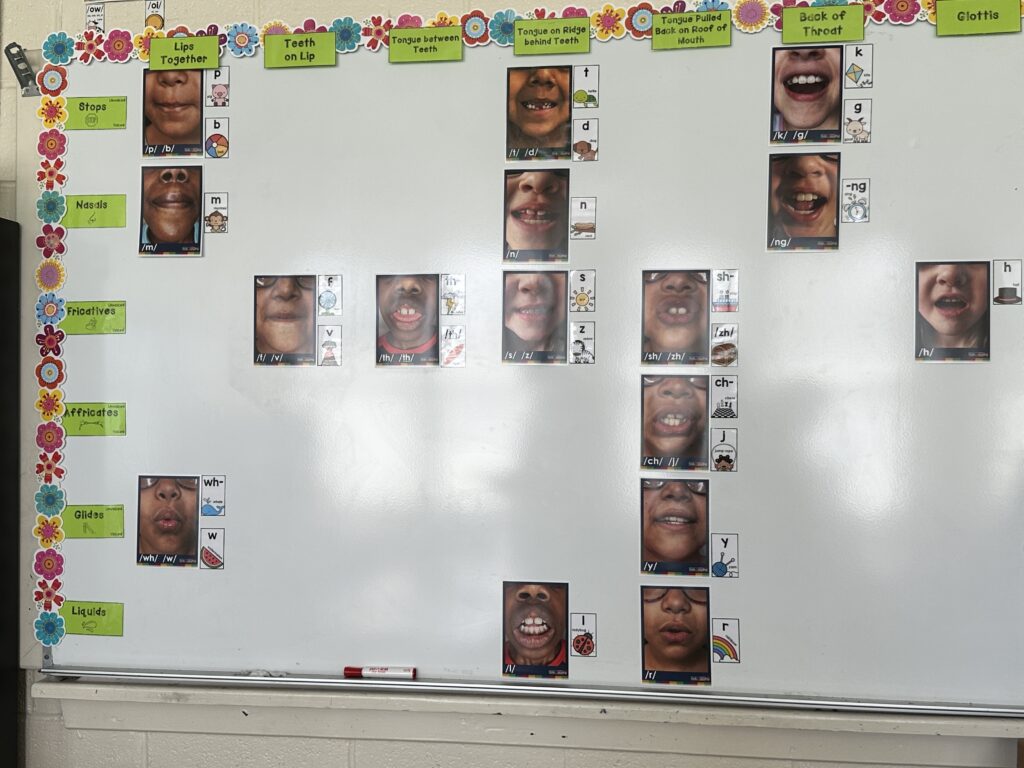

The district’s gains in literacy are a fine example of the year-long reform efforts. Roseboro said Language Essentials for Teachers of Reading and Spelling (LETRS) training, and instruction using the science of reading, were helping teachers become more student-centered. She then pointed, again, to how the district empowers teachers to deliver science-aligned instruction, with an agile intervention approach that ensures core instruction “plus more.”

The result of student-centered, teacher-empowering literacy changes? The elementary students’ reading proficiency rose significantly.

The district identified Carlie Davis, a high-flying educator at the elementary school, as someone ready for an advanced role. The district encouraged her to apply to DPI for a position as an early literacy specialist (ELS). Early literacy specialists are housed within the district but work for DPI. Their roles are to support implementation of science of reading, while also providing coaching support.

Davis conducts mini professional development sessions with teachers at the elementary school as they progress through LETRS.

“The main things I’m focusing on this year are science of reading implementation … and data assessment,” she said. “Right now, I’m working with teachers to make sure we have fidelity with the way we’re giving assessments.”

Specialists like Davis, Truitt said, are game changers.

“When we look at the Amplify data, districts that are not working with our ELS, their scores are not as high,” Truitt said.

‘Blue party’ celebrates the wins

Bridgers scans the crowd during her celebration speech, noting how many stakeholders are needed to move the needle for student outcomes. It’s a long list, and she takes the time to thank all of them.

“This is a testament to the hard work and dedication of all of us — students, teachers, families, and community,” she says.

There are so many things that the district and this elementary school did to turn things around, Bridgers and Roseboro say. Student design and teacher empowerment are pillars, they say, but they also had to look for ways to maximize instruction time, implement a new core curriculum aligned with standards, redesign weekly professional learning community meetings, and hold regular “data days” to see how students were responding to changes.

It’s hard work, Roseboro says, so they demanded hard work from everyone in the school building. And while this ‘blue party’ is well-earned, Bridgers takes a moment to set a new goal. Her elementary school, she says, can do better than exceed growth — it can be an A school.

“We have the talent, dedication, and support of our community to make it happen,” she says.

Recommended reading