Share this story

- Some are hailing a possible agreement between federal lawmakers on extending child nutrition waives past their June 30 expiration date. But the proposed legislation leaves out one big thing.

- Would a new agreement on child nutrition waivers keep all programs in place as they have been during the pandemic? Here's what's happening with proposed legislation.

|

|

Editor’s Note: Congress passed the nutrition waiver agreement Friday. Read about it here.

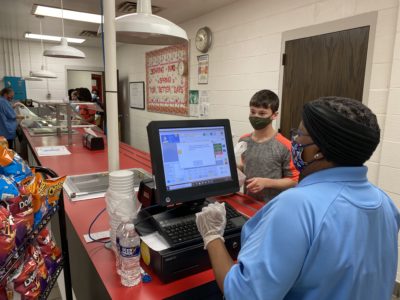

A possible federal agreement on extending child nutrition waivers for schools around the country has some district leaders confused: Would this agreement continue the child nutrition program as its been operated during the pandemic, or is it different?

Short answer: It’s different.

This week, two congressional Democrats and two Republicans — including North Carolina’s Republican U.S. Rep. Virginia Foxx — filed legislation to extend child nutrition waivers.

Under the legislation, all waivers would stay in place through the end of this summer, ensuring that summer nutrition programs can continue as they have throughout the pandemic, including the option to offer meals in a grab-and-go or drive-thru model.

The bill includes waivers that allow schools to be flexible if they can’t meet nutrition standards. Schools that stray from nutrition standards won’t be punished monetarily or otherwise, according to Lynn Harvey, director of school nutrition services at the state Department of Public Instruction. This is important because supply chain problems may make it difficult for schools to meet those standards.

For next school year, the bill also includes increased reimbursement for meals and allows students to eat for free if they are eligible for reduced-price meals. North Carolina already has financial support from the state General Assembly to ensure that reduced-price eligible students can eat for free, even if this deal doesn’t go forward.

But here’s the big thing: The bill does not continue the free-meals-for-all that schools have been able to provide during the pandemic.

Sign up for the EdWeekly, a Friday roundup of the most important education news of the week.

Julie Pittman, special advisor on teacher engagement to state Superintendent of Public Instruction Catherine Truitt, said that going back to the way things were before the pandemic could be problematic. She said that filling out the forms required to qualify for free or reduced-price meals is onerous and also carries stigma.

During the State Board of Education meeting earlier this month, Harvey said that the free meals were one of the most important aspects of federal waivers, and she further discussed the issue of stigma.

“Many children who are unable to afford meals at school suffer that stigma of other children knowing that their household lacks the income,” she said, adding: “This certainly has an adverse impact on students social and emotional well-being.”

In an interview today, Harvey talked further about the harm that may be caused by eliminating the option to provide free meals for all children.

Children from families that are at 130% of the poverty level or below qualify for free meals — that’s an annual income of about $36,000 or less for a family of four. Children between 130% and 185% get reduced-price meals (an annual income of about $36,000 to $51,300 for a family of four). But, with the increase in prices of things such as fuel, food, and other items, there may be families that don’t reach either threshold and still have hungry children.

“As many local boards of education have really had no choice but to increase their paid student meal price, there are some families that simply will not be able to afford that meal,” Harvey said, adding later: “How are we going to address these students whose families are economically distressed for whom food in the household remains a challenge?”

And she said that last question is one school nutrition leaders have been puzzling over for years, not just during the pandemic.

She said that school nutrition programs will never go back to the way they were prior to the pandemic. School nutrition leaders are focusing on making sure school meals are accessible and attractive to students. Building student participation is essential, not just for ensuring children eat well, but also because the revenue collected from paying students keeps school nutrition programs sustainable, Harvey said.

She also said she was thankful for North Carolina’s congressional delegation and their action to provide some relief, as well as the work of state leaders in pushing for a solution.

“I’m confident their work to bring attention to this has been instrumental in moving it forward,” Harvey said.

Last week, State Board of Education Chair Eric Davis and Truitt sent a letter to North Carolina’s Republican U.S. Senators Richard Burr and Thom Tillis asking for help getting the waivers extended past their June 30 expiration date.

“School meals will be jeopardized for thousands of North Carolina students who depend upon them as their primary source of food during the week,” they wrote. “While we all want to put the pandemic behind us and resume normal operations, school nutrition programs are not able to return to ‘business as usual’ for the 2022-23 school year.”

In response to the potential agreement, Truitt tweeted:

But the legislation needs to actually pass before the waivers can be extended and, as mentioned above, they expire June 30. According to No Kid Hungry, an advocacy group focused on ending childhood hunger, there is opposition to the bill:

Here is a fact sheet on the legislation.

Recommended reading