|

|

At Church Child Care in Walkertown, a private child care center in Forsyth County, director and owner Theressa Stephens has lost four teachers in the last year. There is a classroom in her center with 18 empty pre-K seats because she can’t find a teacher with the right qualifications.

In elementary schools across the public school district, Teressa Beam, director of early learning, is hoping pre-K enrollment returns to normal after dropping by almost half during the pandemic. And even in normal circumstances, space, transportation, and wraparound care are barriers to reaching more students, Beam said.

At Forsyth Technical Community College, Phygenia Young, the chair of teacher education and human services technology, said enrollment in the early childhood program has been in decline since 2015. Though she knows many students who have a passion for early education, she said low pay makes it hard to recruit people into the profession.

“Hunger pains will make you change that quite quickly if you can’t supply your needs for your own family,” Young said. “It’s very, very difficult.”

A new local early childhood task force is grappling with these issues and more with a goal of expanding high-quality pre-K to be available to all 4-year-olds in Forsyth County.

Years of looking within and outside of the community have revealed several lessons and challenges for pre-K expansion.

Information is hard to come by

To know where to start in tackling systemic issues, local early childhood leaders have been digging for information on the current landscape.

“Obtaining information about this system is extremely difficult because it is so fragmented, because there is no central repository of everything,” said Bob Feikema, president and CEO of Family Services, the local Head Start grantee and member of the Pre-K Priority, a coalition of local organizations who have been advocating for pre-K expansion since 2014. “It’s here, it’s there, it’s everywhere.”

In the one year before kindergarten, Forsyth County children are in a variety of settings: at home, with family members or friends, in private child care centers or community-based programs, in public classrooms within an elementary school or a private center or a Head Start center.

When it comes to publicly funded pre-K slots, providers use a variety of funding streams to cover the cost of caring for and educating children: the subsidy program, Smart Start funds, Title 1 funds, NC Pre-K, Head Start, and Exceptional Children’s grants. Parents sometimes still have to cover a portion of the cost or pay for wraparound care to accommodate work schedules.

Looking at information from all of those sources and programs gave advocates a starting point.

The local landscape is complex

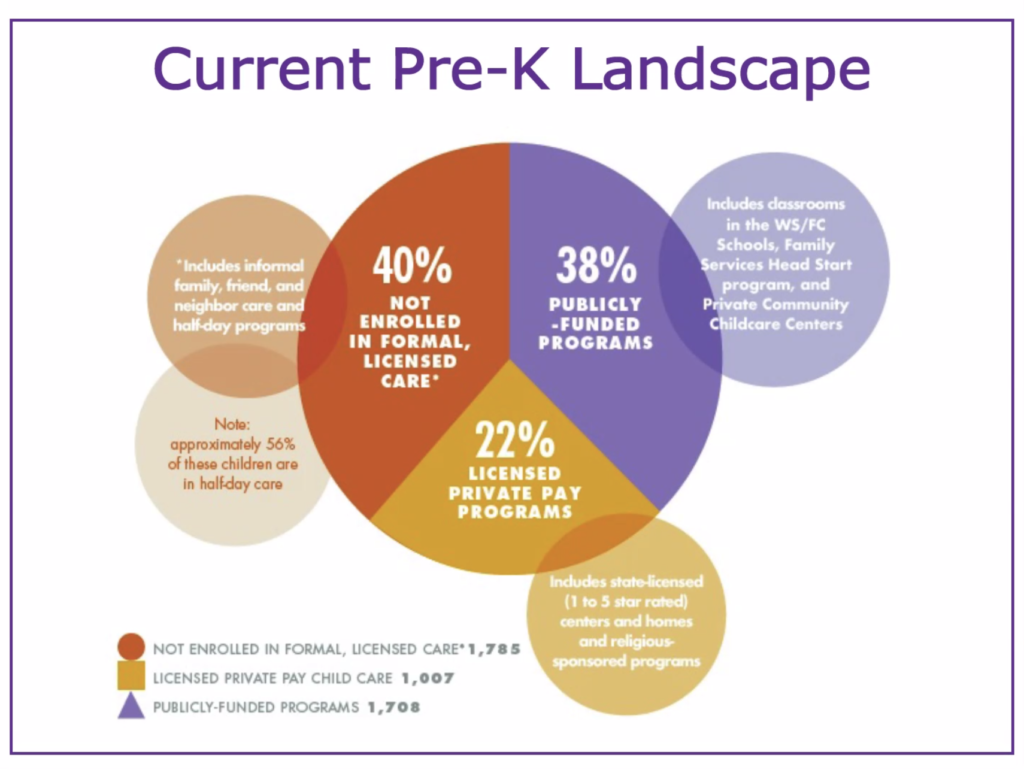

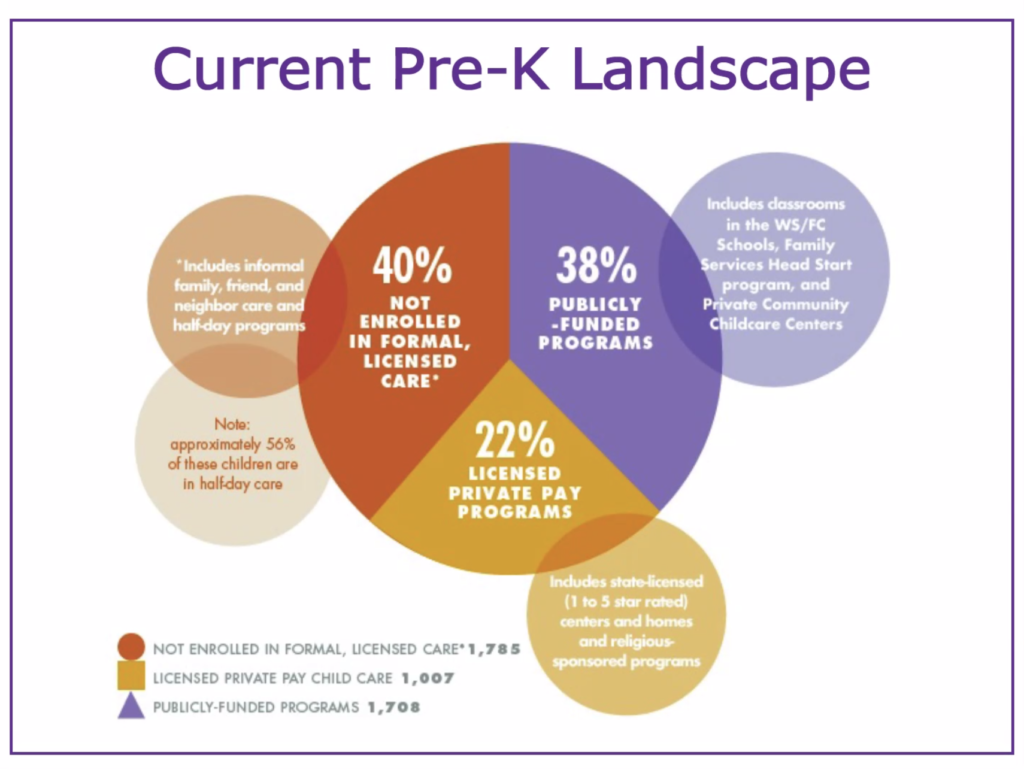

Out of about 4,500 Forsyth County 4-year-olds, Pre-K Priority estimates about 38% are enrolled in publicly funded programs, 22% are in licensed private-pay programs, and 40% are not enrolled in formal pre-K settings.

Feikema said the group has found about 56% of those not enrolled in formal care are in half-day care. Others participate in unlicensed or family, friend, and neighbor care.

“What this says to me is that our parents have already voted in terms of what they want for their young children, which is to have access to high-quality and affordable pre-K programs,” he said during the task force’s first meeting.

A 2019 Pre-K Priority report found about 33% of 4-year-olds were enrolled in high-quality publicly funded programs, and that 31% of 4-year-olds were eligible for publicly funded programs but were not enrolled.

If you only look at NC Pre-K, the state’s public preschool program for at-risk 4-year-olds, only 26% of eligible children in the county were enrolled in 2019-20. Eligibility is mainly determined by family income, but other factors like limited English proficiency and special needs are also considered.

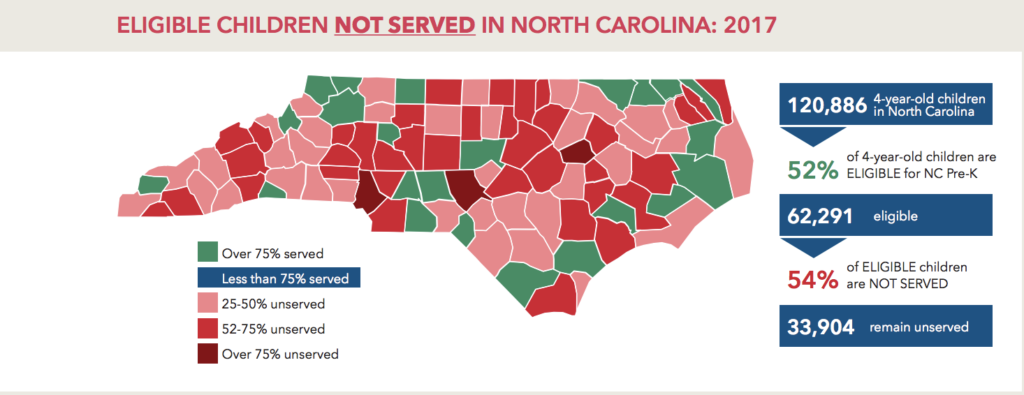

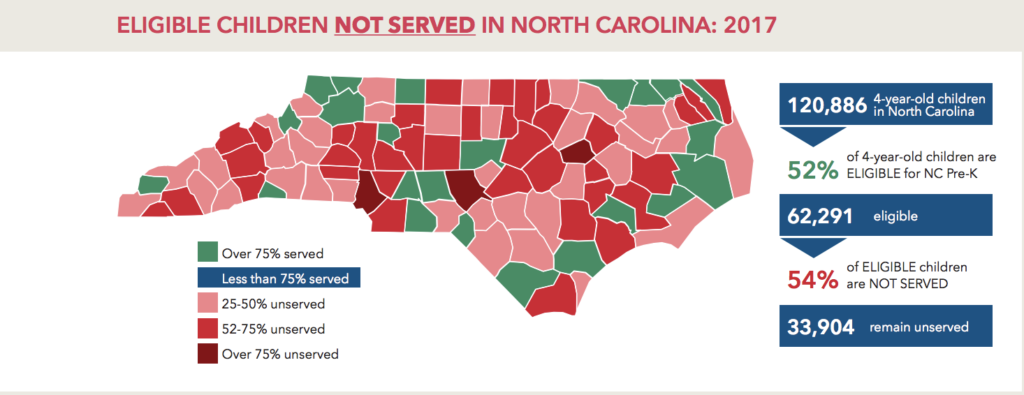

This 2019 report from the National Institute for Early Education Research at Rutgers University shows the percentage of eligible children not served in 2017 across the state. Forsyth fell in the 52-75% range with 37 other counties.

Resources and access vary greatly across the state

“Currently Forsyth County local government invests $0 in pre-K education,” reads a full-screen statement on the Pre-K Priority’s website.

Though advocates are hoping that changes, there are statewide disparities the task force is hoping to draw attention to outside of their community.

“You have this incredibly unequal distribution of NC Pre-K slots,” said Don Martin, chair of the task force, county commissioner, and former superintendent of the local school district. “So that’s a big issue, child care subsidy differences are a big issue at the state level … There’s some Raleigh stuff that needs to be addressed.”

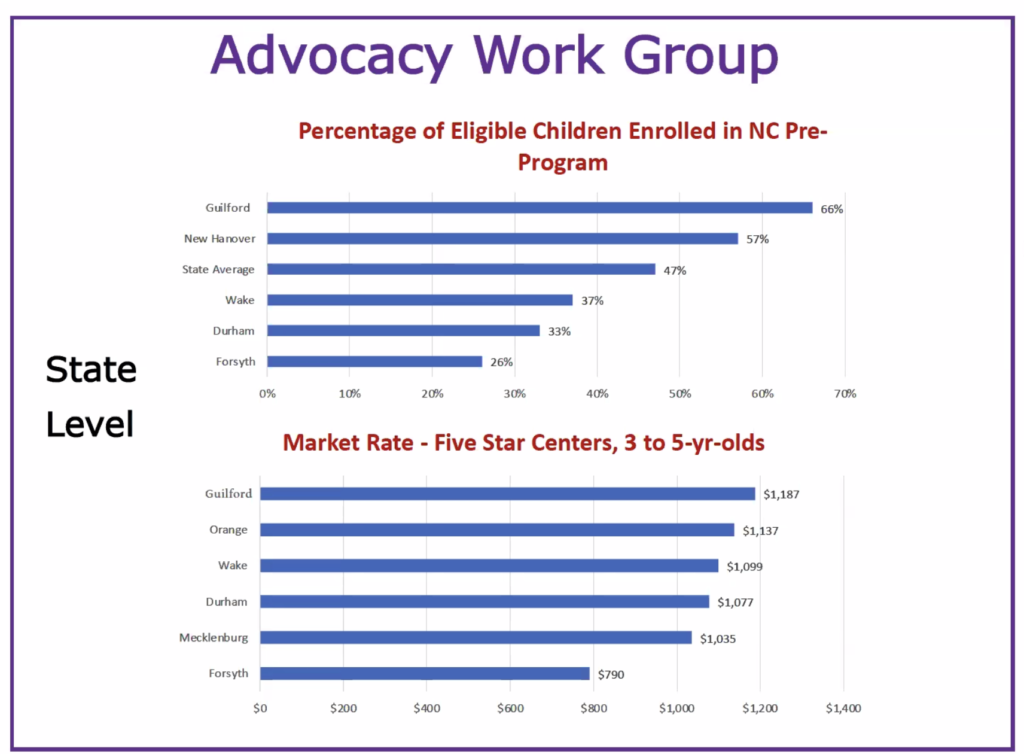

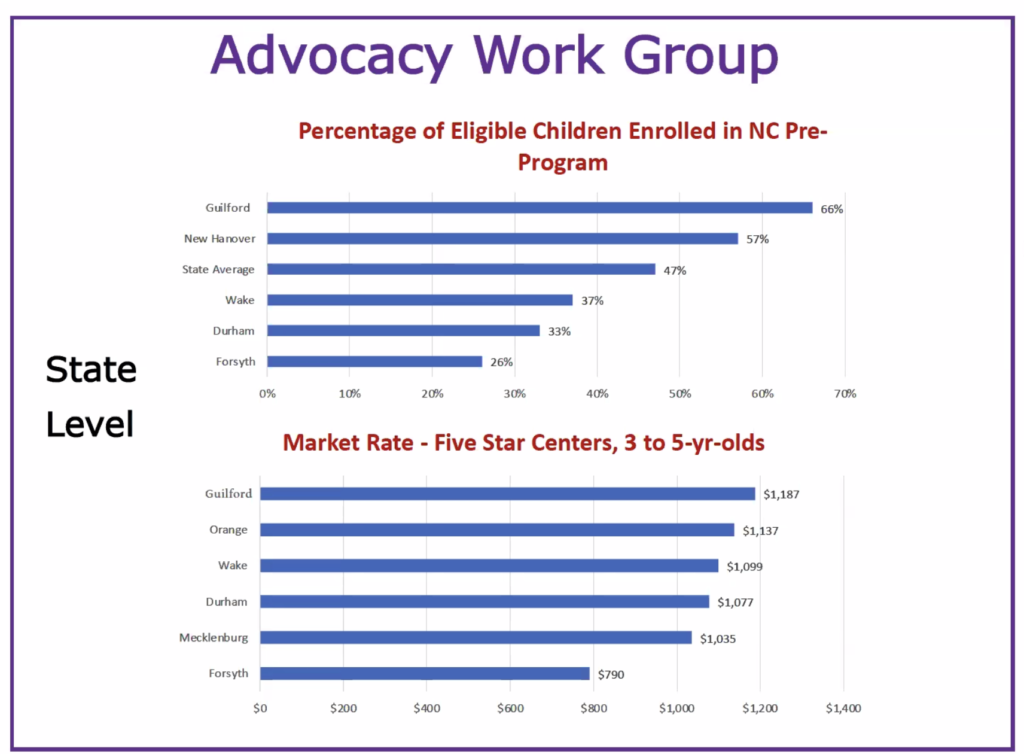

The image below contains two graphs. The first compares percentages of eligible children enrolled in NC Pre-K in multiple counties, based on data from the Division of Child Development and Early Education (DCDEE). Forsyth’s neighboring county, Guilford, enrolled 66% of eligible children in 2019-20.

Feikema said he started to ask why.

“Did we not have enough space? Did we not have providers who could meet the standards that are required? Did we not speak up for ourselves and say, ‘Hey, we need more slots?’ Did we not have the ability to provide the match? … Were we as a community not paying attention to this? … I think all of those are a part of the answer to why we wound up where we are now as a county.”

The second graph below is the rate providers who earn five out of five stars in the state’s rating system receive to serve children whose parents receive subsidy assistance. Families who fall under certain income thresholds with parents who are working or going to school might qualify to have a portion of their child’s care covered.

The program is funded with a combination of federal and state funds, and the state legislature sets the rates providers in different counties receive. Though centers must meet the same standards, the rates they receive vary greatly depending on location.

As is shown in the graph, Guilford County providers receive $1,187 per child. Durham County receives $1,077 per child. Forsyth County centers receive $790. Halifax County centers, which are not included in the graph, receive $571 per child.

Though Feikema has been studying the internal early education landscape for seven years, he said these numbers surprised him.

“We didn’t know two years ago for sure that there were these rather striking disparities in how funds are distributed and how many slots there are in different counties,” he said.

Feikema started to make connections as to why quality was an issue with Forsyth pre-K providers, as found in a 2020 feasibility study.

“Maybe it’s not surprising that quality is where it is because we’re not getting the money that you need in order to produce quality,” he said.

The distribution of subsidy funds also affects the ability for high-quality pre-K expansion.

“All of those things are intertwined,” Feikema said. “Maybe we weren’t able to ask for more NC Pre-K slots because we didn’t have enough centers that could meet those standards and centers that weren’t getting reimbursed enough for the subsidy in order to have the quality that would enable to them to be an NC Pre-K provider. So it’s kind of like these chains of things that are all connected. That’s why we as a group that was focused on pre-K have seen the market rate to be a critical issue for pre-K even though it addresses a broader range of children. Unless we have a market rate that sustains and supports high-quality programs, period, we’re going to have a more difficult time having a high-quality pre-K system.”

This is an issue statewide advocates have been pushing to change, proposing a floor rate that levels the distribution of funds. Proposed legislation in the state House would raise the rates and provide a floor to ensure providers are not at a disadvantage because of parents’ ability to pay.

“These are state issues that have tremendous local implications,” Feikema said.

To local leaders, a mixed delivery system is an asset

Pre-K looks different in different places across the state. In Forsyth County, Feikema said the mixed delivery system — having pre-K within both private and public settings — is an important feature.

Not only does including both settings provide more space, but it provides options that meet families’ needs, said Leslie Mullinix, Pre-K Priority project coordinator.

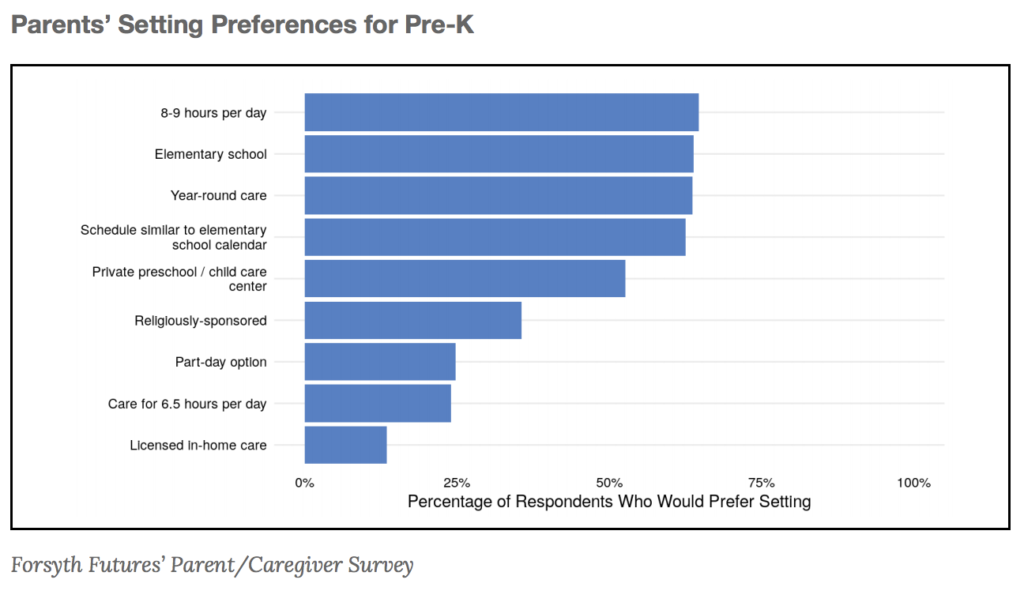

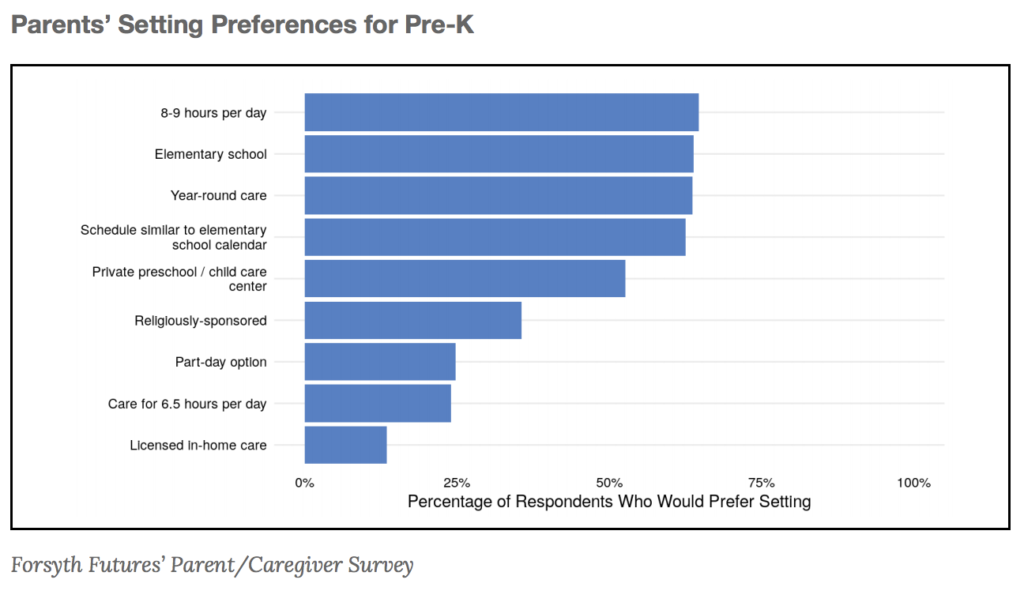

“We’ve got such a robust system already, a landscape here that’s been able to serve people with different needs, different preferences, and so we wanted to build on that and not recreate something that wasn’t what people wanted,” Mullinix said, pointing to the feasibility study in which some parents preferred elementary school settings, while others preferred private child care settings. “Parents want choices about where their kids are.”

Research in New York City has shown public pre-K investments can have negative impacts on infant and toddler care availability in the area. When pre-K expansion means private providers lose revenue by preschoolers going to public schools or by investments that don’t cover the full cost of care, experts say the availability and quality of infant and toddler care can be weakened.

When public schools can offer higher wages or more benefits, private providers also struggle to find and retain pre-K teachers.

Feikema said he thinks pre-K could lift the entire early care and education system.

“We know that private providers often times depend on the income generated by services to 4-year-olds to, in many ways, make up for the lack of sufficient funding for infants and toddlers,” Feikema said. “We need to make sure we’re not draining from the larger system in order to support pre-K, but there’s another argument that could be made that by strengthening pre-K, you actually begin to strengthen the whole system and set the foundation for even expanding into the rest of the system.”

The early childhood task force includes parents, as well as early childhood providers from multiple settings.

Beam, the early learning director from the school district, said she’s excited to hear from families.

“We need to listen to what the needs are in the communities instead of us going in and saying this is what you need.”