The Public School Forum of North Carolina’s Dudley Flood Center for Educational Equity and Opportunity held its first webinar of the Flood Center Student Voices Series today.

Titled “What does culturally responsive curriculum mean to our students?” the webinar discussed culturally responsive curriculum as a part of educational equity. Students shared what they do and do not see in the curriculum in their schools.

KaLa Keaton, a senior at Middle Creek High School in Wake County, said that experiencing classes with a culturally diverse history forces her to think about other perspectives and different socioeconomic statuses, religions, genders, etc.

“It’s really forced me to think and deviate from the traditional story of America,” she said.

Keaton, a Black student, was one of three students who participated in the student panel discussion. The other two were:

- Kaloni Walton, a senior at Lumberton High School in Lumberton, North Carolina. Walton is a member of the Lumbee Tribe of North Carolina.

- Abby Rogers, who graduated last year from Middle Creek High School. Rogers is white.

Keaton also said that looking at history through a diversity of perspectives has made her enjoy discussions about people’s ideas more.

“I love hearing what other people have to say and how they got there,” she said.

Rogers said that culturally diverse curriculum has helped her to “become more competent when I’m conversing with other people, particularly adults.”

Keaton said that classes with culturally diverse curriculum also change the way she experiences other classes. She talked about her history classes before high school and how different they were.

“I took history at face value and I didn’t read into it anymore,” she said. “I wasn’t presented any other diverse perspectives to kind of reconsider what I’m reading.”

Now, after experiencing a culturally diverse curriculum, she looks differently at all her classes.

“I’m a little bit more critical of the information and the sources that are presented to me,” she said.

The student panel today was the first in a series that will explore a variety of issues including diversity in STEM, equitable access to educational opportunities, and more.

Mary Ann Wolf, executive director and president of the Public School Forum, launched the webinar by talking about the importance of listening to students.

“This is a really important day for the Public School Forum and the Flood Center as we launch into this work,” she said.

She said that student voices are important for making sure adults don’t ignore important aspects of education.

“Our students are going to help us really understand what’s happening,” she said.

Ashley Kazouh, a policy analyst with the Dudley Flood Center, prefaced the student panel discussion with a definition of culturally responsive curriculum and pedagogy:

“Using the cultural knowledge, prior experiences, frames of reference, and performance styles of ethnically diverse students to make learning encounters more relevant to and effective for them,” the definition stated.

The student panel was followed by one with educators. The panelists were:

- Leslie A. Locklear, program coordinator for the First Americans Teacher Education program and First Americans Educational Leadership program at the University of North Carolina at Pembroke. She is a member of the Lumbee, Waccamaw Siouan, and Coharie tribes.

- Matt Scialdone, an English teacher in Wake County Public Schools. Scialdone is white.

- Rodney D. Pierce, a middle school Social Studies teacher in Nash County Public Schools. Pierce is Black.

- Erin Berry-McCrea, curriculum coordinator at the North Carolina Virtual Public Schools. Berry-McCrea is Black.

Pierce said that when he thought about introducing a culturally diverse curriculum in his classes, he focused on place-based curriculum.

He teaches in Nash County now, but he started out in Halifax County. He said that when he was teaching there, he dug into the history of the county, which included the three major demographic groups of the county: white, Black, and Indigenous people. He looked at how the history of those three groups intersected, be it through economics, slavery, or other areas of overlap.

And then he was ready for his students.

“I brought it to the classroom because the demographics of the county never changed,” he said.

But, he said, now that he is in Nash County, he has to take a different approach, because the demographics of that county are different than Halifax.

Berry-McCrea said that in her classes, students are going to talk about the social constructions of race, class, and gender that “undergird” everything they experience in their world.

She said that when students leave her classroom, they have a better understanding of how to do social justice work and be culturally competent.

Scialdone said that the uncomfortable moments are the most important ones in his classroom when it comes to culturally diverse curriculum.

“That idea of sitting in that discomfort and pushing through it with the kids. It’s that moment that I think holds the most learning potential for the kids,” he said.

And Pierce stressed the importance of having the support of school and district leaders when it comes to trying to get more culturally responsive curriculum into classrooms.

“Sometimes when you want to share this stuff with your colleagues, they’re not going to be interested,” he said.

When it comes to making sure your students feel safe in the classroom, Locklear said she makes sure her students know who she is. She said that the inclination for a lot of teachers is to come in and pretend to be all knowing, because that’s how their teachers were when they were growing up. She makes sure not to do that.

“I always start my conversations by being really honest about what I do know, what I don’t know,” she said.

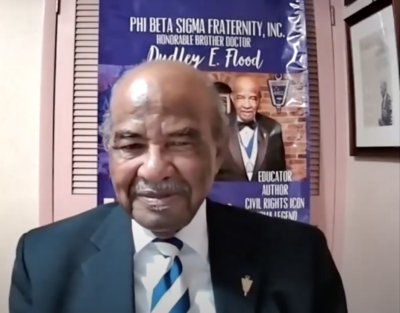

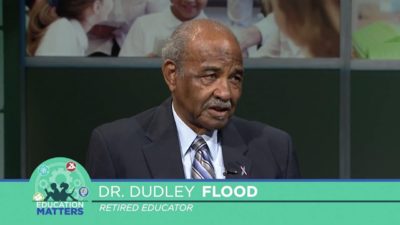

The program ended with closing remarks from the Center’s namesake: Dudley Flood. Flood, an educator who spent years working to integrate the state’s public schools, said that “The great motivator is possibility.”

He said that if a person has never been exposed to anything but one way of thinking, that person can’t imagine a possibility that there is anything greater than what they’ve been exposed to.

He also talked about his nephews who, during car trips, would always ask him if they were there yet. He said he found “yet” to be a gratifying word, because it meant that his nephews knew they would arrive eventually.

He applied that line of thought to the work that he and others are doing.

“We’re not there yet,” he said. “We will get there, but we will only do that if we keep the faith and believe that there is a destination.”

More installments of the student voices series is coming in the months ahead. Go here for more about the Dudley Flood Center.