Every year, the Belk Center for Community College Leadership and Research at N.C. State hosts the Dallas Herring lecture — a tribute to the founder of the North Carolina community college system and a forum to discuss top issues facing community colleges.

This year’s lecture featured Dr. Pam Eddinger, president of Bunker Hill Community College in Massachusetts, who shared her thoughts on “the reckoning and hope” the pandemic has provided community colleges.

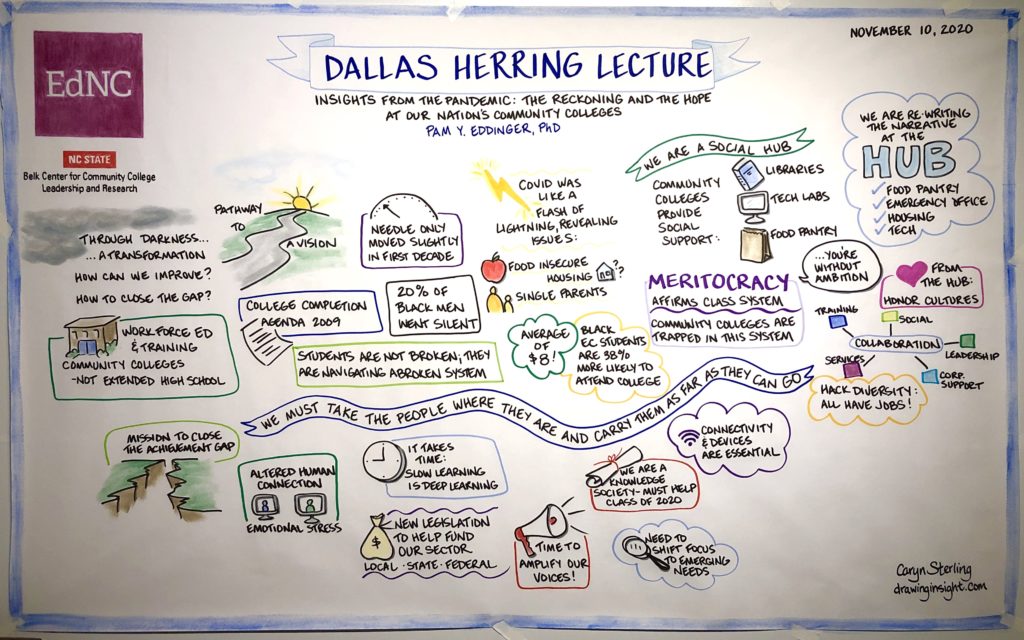

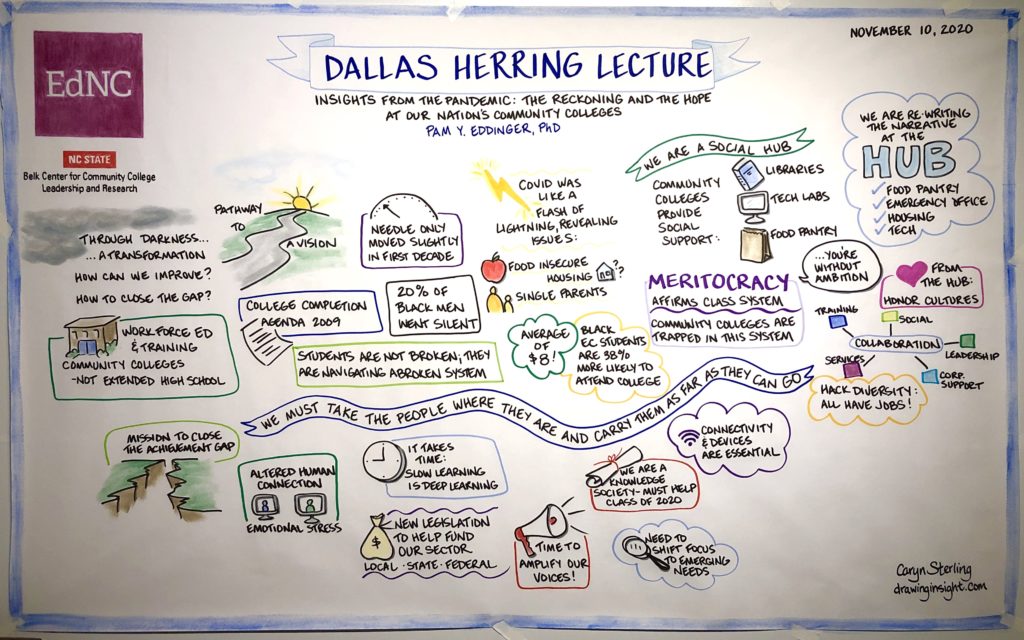

Eddinger used the metaphor of a lightning bolt to describe how the pandemic exposed decades of systemic inequities. Yet she said the pandemic also showed the capacity for community colleges to “become holistic, equity-minded institutions that promote community engagement, economic mobility, and ultimately, social equity.”

Prior to the pandemic, Eddinger said, community colleges focused on two questions: 1) How can we improve student persistence and increase completion? 2) How can we close the achievement gaps in our marginalized populations?

Yet despite years of intense reform efforts, little progress was made in addressing these issues. What they came to realize, Eddinger said, is the “critical understanding that community college is deeply entangled with social, racial, and economic forces, and the effects of these systems are interdependent and impossible to tease apart.”

The pandemic laid bare the interdependence of these systems, Eddinger said.

“Like a flash of lightning in the night, the pandemic revealed all the cracks and fissures hidden in the landscape and gave us a stark and unsparing look at the cavernous wealth and attainment gap before us in our Black and Brown urban communities, in the immigrant communities, and in our poor white communities in rural regions.”

Dr. Pam Eddinger

Like many urban community colleges, Eddinger’s students are now frontline essential workers, first responders, and health care workers whose jobs have left them exposed to the virus.

“It is no accident that COVID hotspots in Massachusetts and elsewhere coincided with our communities of color served by our colleges where poor public health and public education outcomes are intertwined,” she said.

While the pandemic exposed the frayed social structures supporting their students, Eddinger said it has also exposed the transformative capacity of community colleges.

“But here’s the light amidst the darkness. As much as the pandemic revealed the failure of social and economic systems, it has also shown us a radical transformation in the nature of community colleges.”

Dr. Pam Eddinger

Over the past several months, Eddinger said, community colleges have built libraries, study areas, and computer labs with Wi-Fi; food pantries; clinics; emergency housing; mental health counseling; and other services to support students and keep them connected during the pandemic.

“Maybe college education is no longer a standalone,” she said. “We are the social and education hub for our communities.”

Eddinger then turned to the role of community colleges in economic recovery. Despite years of underfunding, she said, “it is unmistakable that a just and equitable recovery from COVID, one that restores the cultural identity and socioeconomic infrastructure of our communities, depends heavily on us.”

Eddinger stressed the need for an equitable recovery. “We must acknowledge that economic recoveries have most often failed communities of color,” she said, citing data from the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston showing that eight years after the Great Recession, the average net worth of Black people in Boston was $8. “Everyone thought that was a typo, but it was not,” she said.

Eddinger pointed out that historic education legislation following World War II, including the GI Bill of 1944, the Truman Commission of 1946, and the Higher Education Act of 1965, were meant to broaden access to education but were not in fact accessible for Black people and other people of color. In response to the pandemic, Eddinger called for a more just recovery, citing a Brooking Institute report on “rebuilding better.”

“At the heart of the just recovery effort,” Eddinger said, “must be a multi-sector commitment towards a shared vision for economic and social justice.”

Eddinger closed her remarks by calling on her community college colleagues to think about how they can serve as change agents in the coming decades.

“I believe the crack of lightning that was COVID really did light up the inhumane conditions in our communities. And difficult as it is to witness the misery, I think we will seize this moment of clarity to think anew about our role as colleges in our community and how we can be agents of change in the coming decades.”

Dr. Pam Eddinger

Following Eddinger’s remarks, a panel responded to the lecture that included Dr. Avis Proctor, president of Harper College in Illinois; Dr. William Serrata, president of El Paso County Community College in Texas; and North Carolina’s own Dr. Kandi Deitemeyer, president of Central Piedmont Community College.

Panelists spoke to the importance of communicating the return on investment that community colleges provide, especially during an economic downturn. “If you cut community colleges during a recession, you’re actually going to delay a recovery,” Serrata said. “We’re the most nimble institutions that can bring both our credit and non-credit sides of the house to meet those workforce needs and really maximize the return on investment,” Proctor added.

Serrata said his biggest concern right now is to ensure the classes of 2020 and 2021 are not lost from higher education. In the recovery from the Great Recession, 99% of new jobs created required a degree or credential, Serrata said. “We are a knowledge society,” he stated, and higher education will continue to be important as we recover from the pandemic.

Deitemeyer said those non-returners are what’s keeping her up at night. “[How can] we bring back those missing non-returners into a sense of belonging? How do we build back their trust?” she asked.

Proctor added that colleges must be mindful of the psychological impacts of the pandemic. “Typically we would see an indirect relationship with an economic downturn in increased enrollments,” she said. “We’re not seeing that because there are a lot of things that our students in our communities are facing and lots of loss.”

Moving forward, the college presidents said they will continue their focus on student success, completion, and equity. “This is people work, and it’s hard work,” Proctor said.