“Think about a kid’s day,” said Tabari Wallace, the 2018 NC Principal of the Year. Describing a typical day for a student at his school, West Craven High, Wallace continued:

“My students’ days start at 4:00, 4:30. My children get on the bus, they ride 90 minutes to school … then they study with societal expectations on them, teacher expectations on them, principal expectations on them … then lord help if you play an athletic sport or you’re in theater because, now you have to go to practice … now it’s 5:00 and they have 90 minutes to get home … then they get up and do it all over again.”

“Now imagine doing that hungry.”

Wallace’s remarks hung in the air during No Kid Hungry NC’s 8th annual NC Child Hunger Leaders Conference held Wednesday. Child nutrition directors, educators, nonprofit leaders, and child nutrition advocates gathered at the Friday Center in Chapel Hill to share stories and strategies around implementing innovative school nutrition programs to feed hungry children. No Kid Hungry NC works to end childhood hunger by increasing access to federally-funded meals, such as school breakfast, summer meals, and after school meals.

Lou Anne Crumpler, state director of @NoKidHungryNC, says 60% of the 1.5 million public school students in North Carolina qualify for free/reduced-price meals: “Today is about sharing stories and strategies and celebrating the people who work to feed more kids.” #UseYourVoiceNC

— Analisa Sorrells (@analisasorrells) February 13, 2019

According to Feeding America, 1 in 5 children in North Carolina is food insecure, which means they may not have consistent access to enough food for an active, healthy life. While any student attending a school that offers school meals can access them, free- and reduced-price school meals are offered to low-income students. During the 2017-18 school year, almost 682,000 students in North Carolina received free- or reduced-price school lunches through the National School Lunch Program. In the same year, about 397,000 students received free- or reduced-price school breakfast.

For Freebird McKinney, the 2018 NC Teacher of the Year who attended Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools, the experience of eating free- and reduced-price school meals hits close to home.

“For the first time in my life I realized that I was very different from the other kids, and it was made apparent when I got a little card and I went to a different school lunch line,” said McKinney.

He credits one of his elementary school teachers, Ms. Velazquez, for pulling him aside and urging him to “not allow this to dictate you and your voice.”

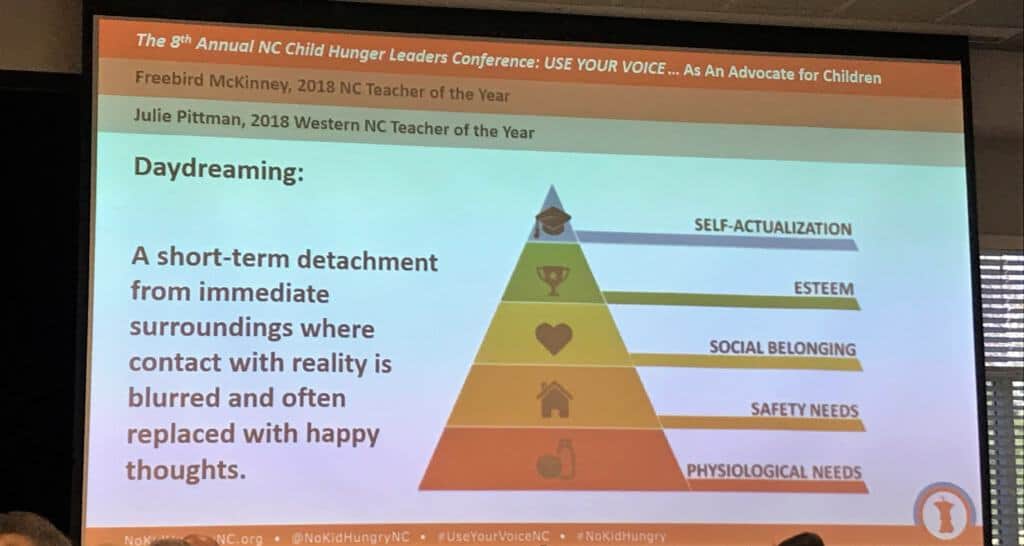

Meeting Maslow’s hierarchy of needs

To open the day, a series of educators, including Wallace and McKinney, shared personal stories of their own experiences with school food, childhood hunger, and efforts to feed their students. The main point they each echoed was this: Before an educator can nourish the mind of a student through teaching, their basic needs — including food, water, and a sense of belonging — must be met.

Julie Pittman, the 2018 Western Region Teacher of the Year from Rutherford County Schools, began by sharing her mantra with conference attendees: Just feed the kids. According to Pittman, about 75 percent of her district’s students qualify for free- and reduced-price lunch, and the entire district is now covered by the Community Eligibility Provision, allowing all students to access free meals regardless of income and without submitting any paperwork.

After sharing details of the adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) she encountered as a young kid, Pittman spoke to how a variety of ACEs — from food insecurity to having an incarcerated parent to experiencing physical abuse — can affect students in the classroom.

“As a teacher, I’m charged with having to look out for those students, with having to try and figure out what’s going on with them. I’m charged with having to make sure there are safety nets for them in the school, that they have counseling, that they are fed, that they are getting all that they need,” said Pittman. “On top of that, I’m also charged to teach. But I can’t do that, unless they have all of their base needs met.”

Closely related to the concept of ACEs is Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, which provides a theory of the order in which basic needs must be met. Displaying the above image, Pittman pointed out the blue triangle at the top — self-actualization — as the true purpose of her job as an educator. But, Pittman said, she can’t really achieve that goal until the other four levels are fulfilled. The red level at the bottom, physiological needs, is where school meals play a crucial role.

“Before we can feed those minds, we have to feed their bodies. We have to feed the kids,” said Pittman.

Reflecting on the conference, McKinney echoed the importance of Maslow’s hierarchy of needs.

“If more people in our communities understood the impact of serving the most basic of our students’ needs like food, water, and shelter, then we can begin to focus on their social and mental needs, as well as their sense of belonging and prestige, the love of community and belonging, and ultimately the process of self-realization and self-actualization,” said McKinney.

Pittman closed her remarks by encouraging the audience to “be a lighthouse” of positivity in the name of feeding North Carolina’s students.

“Education is not about filling a pail, education is about lighting a fire. It’s not about just filling their stomachs, it’s about inspiring those kids to become great, to become part of our goal-setting team, to become part of the solution.” —@twinologist #UseYourVoiceNC

— Analisa Sorrells (@analisasorrells) February 13, 2019

The importance of availability and access

One aspect of addressing childhood hunger is ensuring the availability of federally-reimbursed meal programs, such as summer meals and after school meals. Dr. Mandy Cohen, secretary of the NC Department of Health and Human Services, pointed out one key availability gap during her comments at the conference. According to Cohen, 112 of North Carolina’s 115 Local Education Agencies (LEAs) qualify for the At-Risk Afterschool Meal Program — but only 18 are actively administering it.

“That’s low hanging fruit,” said Cohen. “This is the kind of strategy we need to pursue statewide.”

For an example of one innovative way to address the availability of meals, look no further than Atrium Health University City in Charlotte. Last year, the hospital became the first hospital in North Carolina to serve as a summer meals sponsor and site. Using the professional chefs and cafeteria space on-site at the hospital, kids had the opportunity to eat free breakfast and lunch for 11 weeks.

Elanie Jones, Child Nutrition Manager at @AtriumHealth, says the hospital offered breakfast and lunch for 11 weeks, serving a total of 3,348 meals to students from 12 zip codes. Another impact was improved literacy skills via partnerships with @cmlibrary. #UseYourVoiceNC

— Analisa Sorrells (@analisasorrells) February 13, 2019

But beyond availability, a more complex aspect of addressing childhood hunger is ensuring that students are actually accessing the meals that are made available. A school breakfast served before the bell rings that is only attended by a few students who are dropped off early may not meet the full needs of all students. This is where innovative practices come into play, such as breakfast kiosks or breakfast in the classroom.

Craven County increased participation in school breakfast by 551 percent — from serving 83 students to serving 540 students — by implementing innovative school meals practices.

At West Craven High, a 12-minute “breakfast break” was built into the daily schedule following first period. This break allows students to grab food from one of the school’s breakfast kiosks before heading to second period. It also ensures that more students have the chance to grab breakfast, even if their bus arrives late or they are delayed in getting to first period.

Lauren Weyand, school nutrition director for Craven County Schools, said the implementation of breakfast kiosks allows the school to take the food to where students normally congregate.

“We have kiosks even in the media centers, and you would not believe how many kids we have packed in there eating from the kiosk. So yes, it does take some work from the school nutrition department, but the vision and the end goal of feeding the kids is what drives us to not say ‘no.'”

Later in the day, students are given a “Power Hour.” If a student has a 75 or above in all of their classes, they receive an hour-long lunch break. If they have a 74 or below in any class, they attend lunch for 30 minutes and receive 30 minutes of educational remediation.

“Now we’ve used that basic need as a motivating factor at West Craven High School. Socialization, safety, and making sure that you’re not hungry,” said Wallace.

Ilina Ewen, Chief of Staff to the First Lady of North Carolina, reiterated the importance of addressing access to school breakfast.

“We’ve been to 63 counties so far, and a lot of schools say ‘Oh yeah, breakfast, we’ve got that. We have universal breakfast here.’ What does that mean? It just means they offer it. Does that mean it’s accessible to everyone? Does that mean it’s easy to get to? What does it mean if you’re late to school?” said Ewen. “Just because you offer breakfast, doesn’t mean kids are eating it.”

Through a grant with No Kid Hungry and the Dairy Alliance, Ewen applied to take part in the School Breakfast Leadership Institute. Last summer, a team with representatives from the Office of the Governor, child nutrition services at DPI, and No Kid Hungry traveled to Chicago and received intensive training on how to improve access to school breakfast.

Now, this NC School Breakfast Leadership Team is providing 10 districts across the state with grant funding to introduce alternative breakfast models, like grab-and-go breakfast and second chance breakfast, that reduce stigma and increase access.

“When kids are eating together in a classroom, they’re building relationships, they’re building community, they’re learning manners. It might be the only time in the day they get to sit together and do that. And that counts as instructional time. We’re talking about social-emotional development in children, and we can do that by feeding them,” said Ewen.

For McKinney, the conference served as a reminder that there is a force of advocates working to address childhood hunger and nutrition across the state.

“We felt this is in the room today, from the moment we began talking about our experiences with being a ‘free and reduced lunch kid’ and the impact it had on us growing up … through the stories we revealed of engaged and passionate educators who helped us all to realize that these needs should not diminish our voices, we collectively celebrated our teachers that took broken kids and told us to ‘sing our song.'”

Pittman was most encouraged by the diversity of voices present at the conference, from faith leaders to cafeteria managers to police offices.

“Hunger is not a kid problem, or a family problem, or school problem. It is our problem, and together we can make a huge difference in feeding the kids across North Carolina,” said Pittman.

Editor’s note: Freebird McKinney currently serves on EducationNC’s Board of Directors.