The quality of a student’s relationships with teachers and peers is fundamental for the development of academic achievement and engagement. Student engagement and motivation are critical aspects of the school experience, which are valuable to both students and teachers.

Engagement of both students and teachers provides an anchor for the challenges of schoolwork and promoting students’ motivational resilience.1 Classroom engagement has long term impacts on educational outcomes, including retention across grade levels (particularly in high school), graduation from high school, and successful entrance into college. 2 Engagement is also a protective factor that buffers students from risky behaviors in adolescence, including truancy, gang involvement, delinquency, and risky sexual behavior. 3

An extensive body of research suggests the importance of close, caring teacher–student relationships and high-quality peer relationships for students’ academic self-perceptions, school engagement, motivation, learning, and performance. Children who experience lower-quality relationships with their peers—who are rejected or socially isolated—are more likely to become disenfranchised from school and drop out. 4 5 6 7 8 9

Creating authentic relationships with and between students takes time, commitment, and purpose. One way to initiate these relationships is through Community Connections. A simple activity that can take as little as 20 minutes can kick-start the conversations that, through continued effort, will build those sustainable relationships.

Instructional how to:

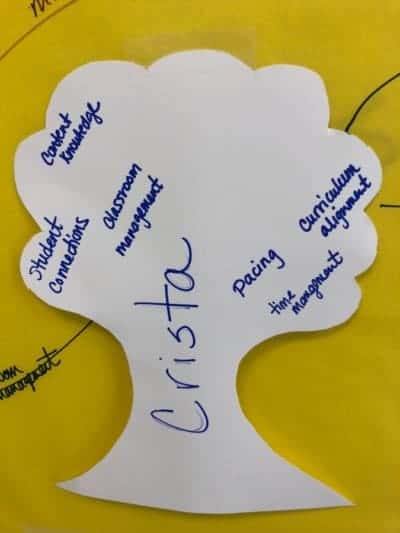

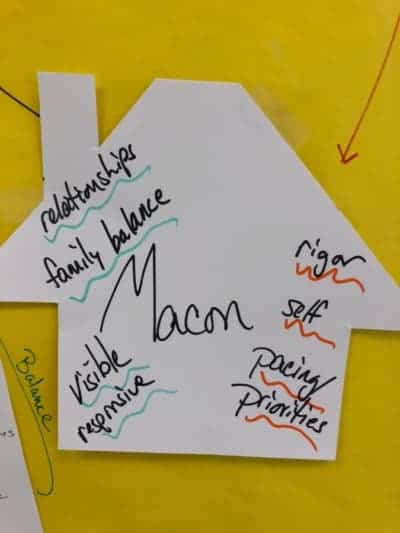

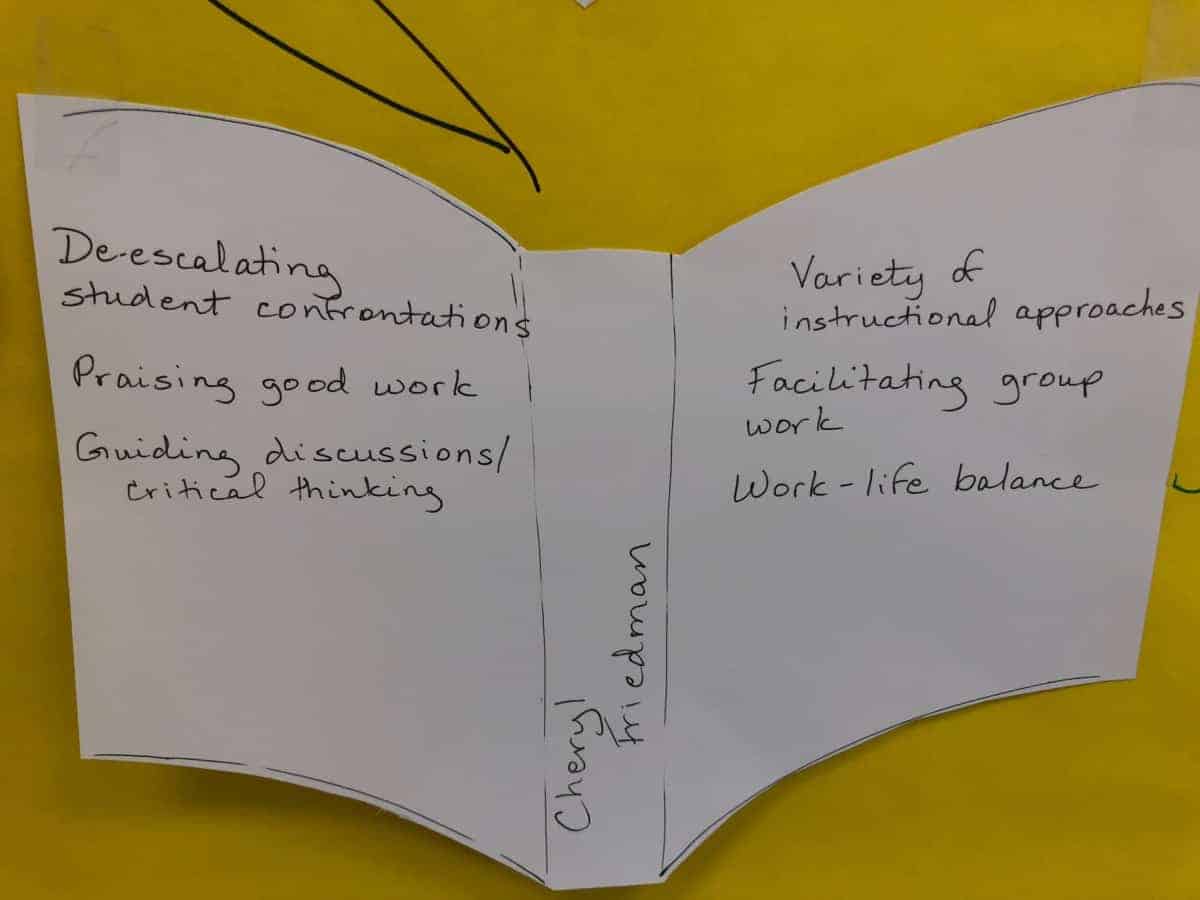

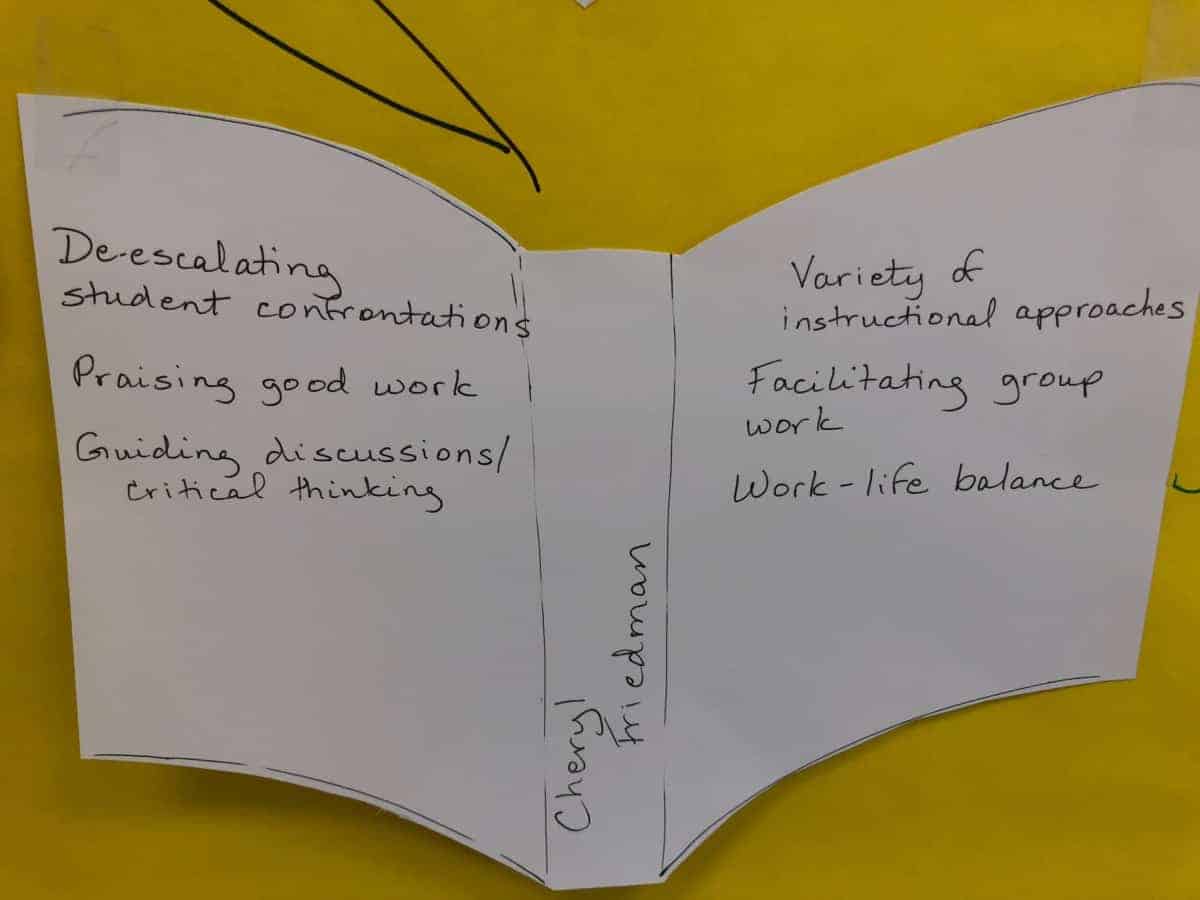

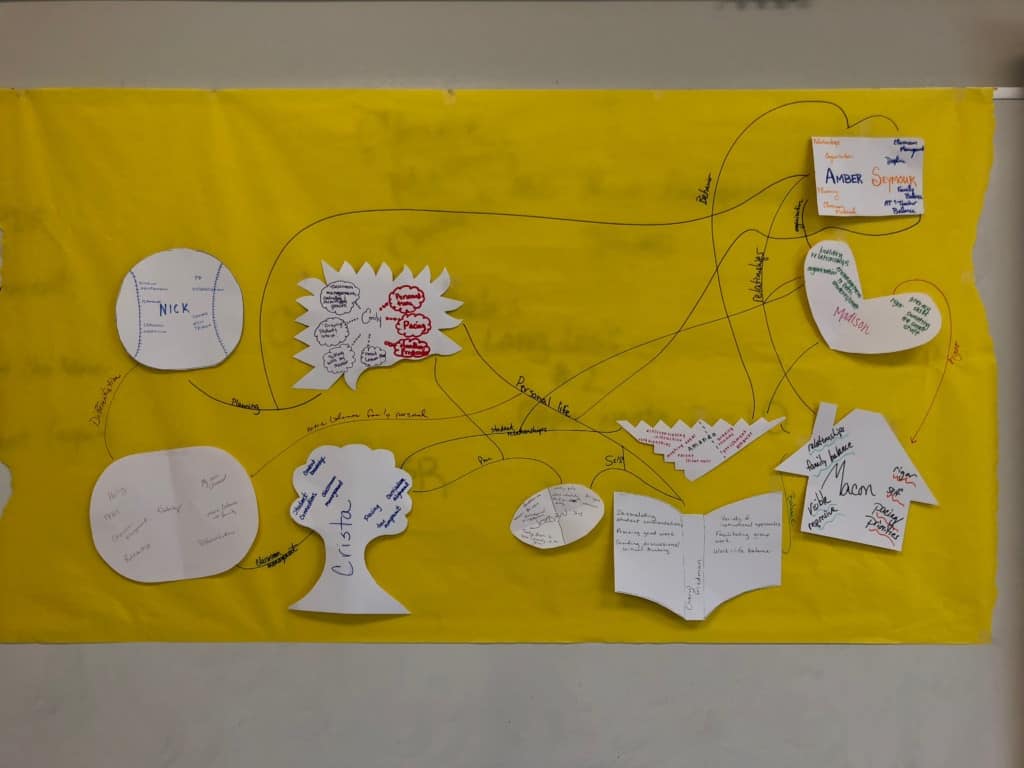

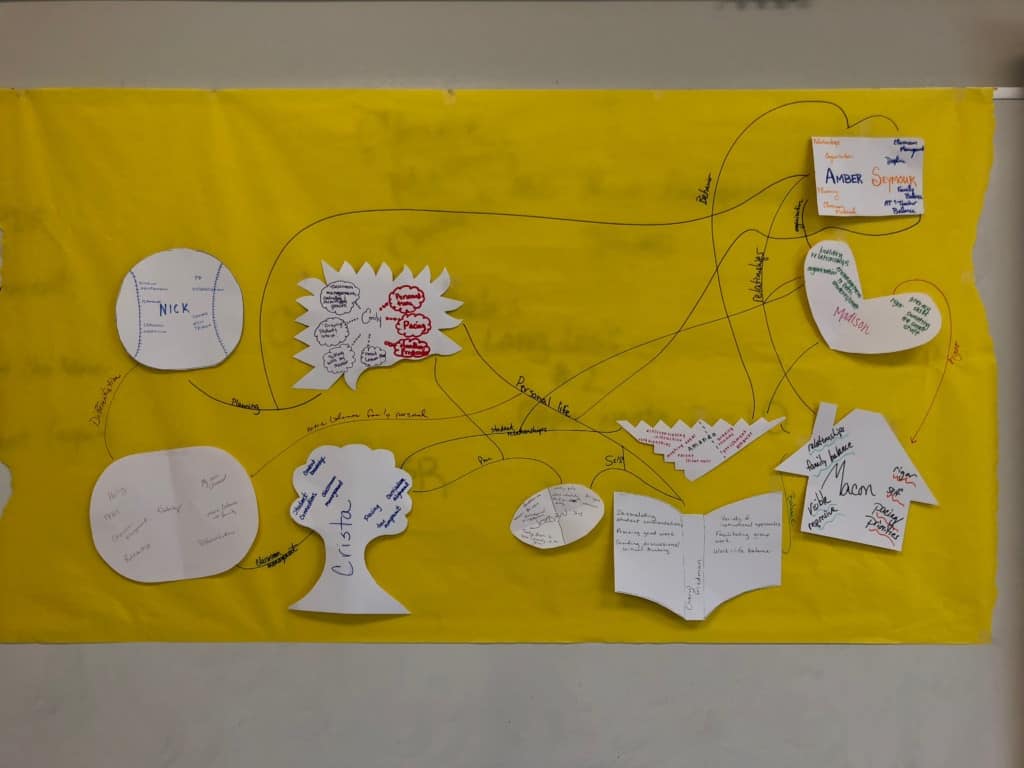

Students and educator take a piece of plain paper or card stock and cut out a shape that represents themselves, write their name across the middle, and write words or phrases around their name that showcase interests, likes, and culture.

Once each person has completed their shape, tape all of them to a large sheet of bulletin board paper. Each participant walks around the paper and looks for connections between participants. When they see a connection, they draw a line between the two shapes and write the connection on the line.

The goal is to ensure that each participant has at least one connection with someone else in the room. This creates a web of connectedness. In a highly transient population, new students can be added to the web and connected to current students. This will instill a sense of instant relatedness.

Follow up questions and curricular adaptations

After completing the activity and finding connections, the class can discuss these follow-up questions:

- How does it feel to know you are connected to someone in the group?

- What would happen if someone left the group?

- What happens if someone joins the group? How can we include them?

Curricular adaptations to this activity can include the following:

- Linking historical figures, artists, authors, etc., to the students based on biographical information

- Utilizing the format to connect characters from a piece of literature based on textual references

- Linking types of literature or art based on common factors or influence

Check out the video to see an example of Community Connections with beginning teachers and their mentors who connected over aspects of their jobs they felt they had mastered and their areas for growth.

Feel free to reach out for more details around this activity (Amanda.macon@cabarrus.k12.nc.us).

This is just the beginning for EdAmbassadors. In our first year, we hope to continue to develop and explore how to involve all teachers around North Carolina. If you are interested in joining the conversation and becoming part of the effort, join below.