How states fund education is complex and has consequences for equity and innovation in schools. North Carolina’s funding system is antiquated and should move to a weighted student-based funding formula, according to Marguerite Roza, director of the Edunomics Lab at Georgetown University and education finance expert. Roza spoke to the Joint Legislative Task Force on Education Finance Reform on Wednesday.

The task force will not recommend changes to the school funding formula during this year’s short session, according to Rep. D. Craig Horn, R-Union County, but will continue its work in the hopes of producing legislation for the long session next year. Horn said, “It is critical that we do a better job of allocating available funds to our K-12 public education in this state.”

Roza started by emphasizing the importance of the education funding formula. “This seemingly innocuous formula matters. It doesn’t just matter because some schools might get more money than others. It actually matters because it signals who’s making decisions in education and what kinds of resources are available for kids.”

She outlined five goals for every state funding formula:

- It should be equitable, meaning higher-need students get more money.

- It should be flexible enough to accommodate major changes in education over the next 30 years.

- It should be adequate, sustainable, and stable, meaning it must pull from revenue that will be there every year.

- It should be simple and transparent.

- It should emphasize continuous improvement and productivity, meaning it enables schools to get the greatest possible outcomes with the funds available.

In making any decisions about school funding, legislators must consider how the funds will be deployed, whether and how local funds will be used, how much flexibility schools will have in deciding how those funds are used, and how to transition from the current funding formula to a new one.

School funding formula options

Roza outlined five different systems of state funding for education.

The first is student-based allocation (or weighted student funding) where the money follows the student. Districts receive a certain amount of money per student, and they decide what to do with that money. Students with higher needs receive more funding, which is what makes it a weighted system.

In staffing or resource-based formulas, districts receive money for a certain amount of inputs (i.e. teachers, teachers assistants, etc.) based on the number of students in the district. For example, the formula may state that for every 25 children in grades four through eight, the district receives money for one teacher. In this model, the state essentially dictates the staffing model in schools by funding positions.

Categorical or program allocation funding is when the state allocates a set amount of money for specific programs. For example, a state may decide to allocate a certain amount of money for Advanced Placement testing.

Some states do not use formulas but rather have hold harmless or reimbursement systems where they simply give every district the same amount or more money than they gave them the previous year.

Finally, many states use a hybrid system that combines two or more of these funding mechanisms. Most have moved to student-based funding as the base with some categorical funding layered on top of that.

North Carolina’s current funding system

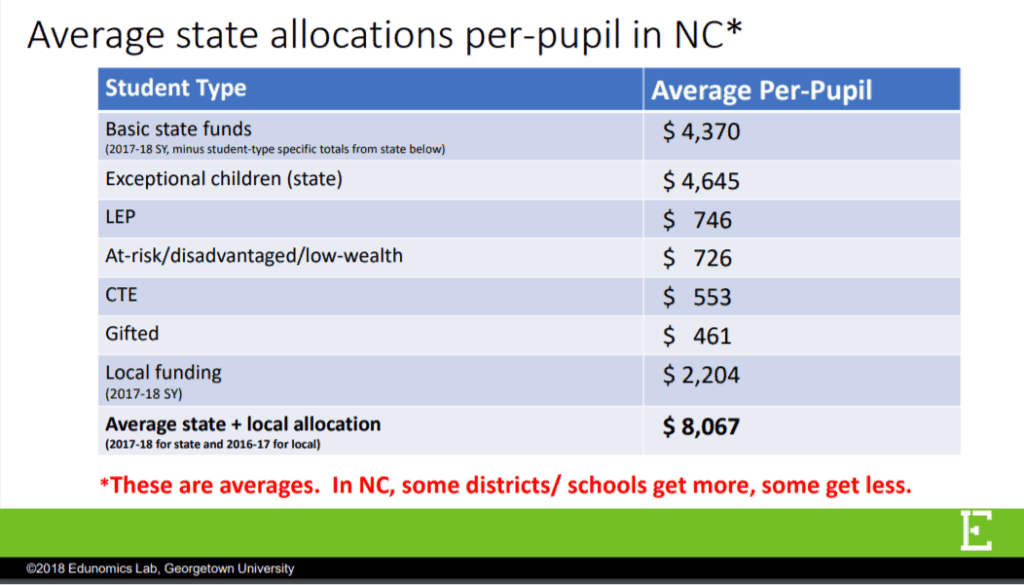

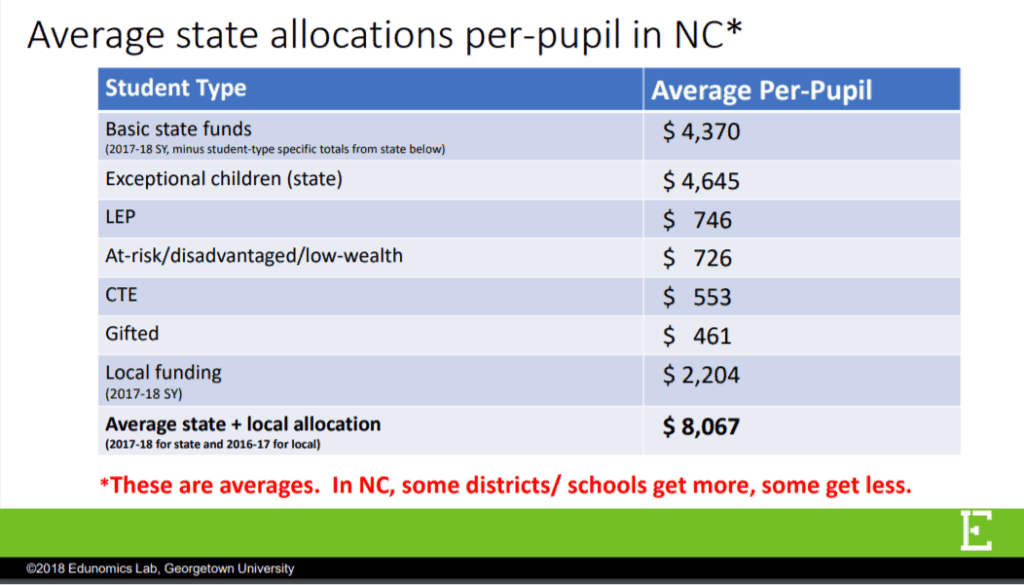

North Carolina uses a hybrid model, combining a staffing-based allocation system with categorical allocations. Roza and her team calculated the average amount of money per student the state allocates to districts in North Carolina, presented in the chart below.

Roza was quick to point out that the Every Student Succeeds Act requires states to publish spending by school starting in the 2018-19 school year, so schools are about to find out whether they receive more or less than the average. When they do, she argued, those schools that receive less money per student than the average are going to blame the legislature.

North Carolina is just one of a few states that still uses a staffing-based formula as most are moving to a student-based formula. Why? Well, according to Roza, staffing-based formulas are inequitable, limit district flexibility, and inhibit innovation.

She said, “Our research suggests that if the state funds stuff like teacher positions, then the district mindset is I must buy those things… We find that in states where the state has the resource [staffing] model, there is much less innovation, exploration, and local problem solving around schooling.”

Roza returned to this point many times throughout the presentation, arguing that staffing-based models inhibit innovation by invoking a mindset in districts that they are simply following what the state mandated: “If you work in a school and the state has funded this many staff [positions] for you, you see your role as executing on a school model that the state chose.”

What do student-based funding formulas look like?

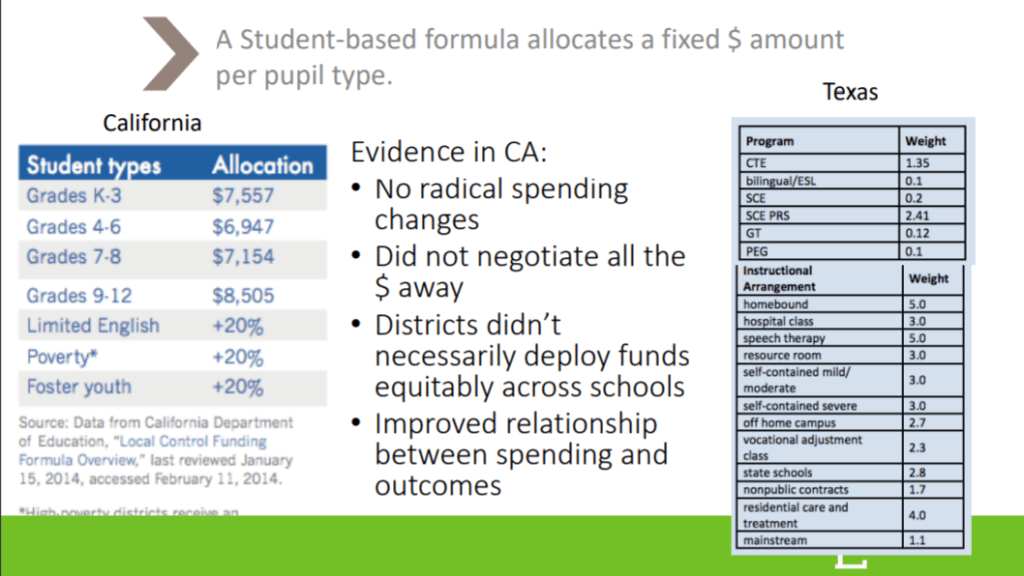

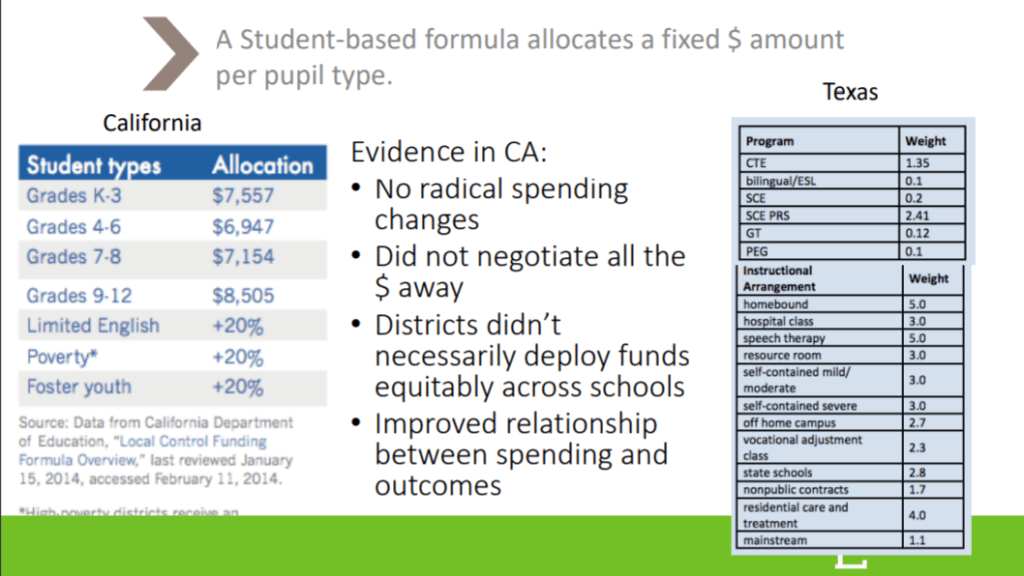

Both Texas and California have moved to student-based funding formulas. In California, the state allocates $7,557 for every kindergarten through 3rd grade student, $6,947 for every 4th through 6th grade student, $7,154 for every 7th and 8th grade student, and $8,505 for every 9th through 12th grade student. They allocate an additional 20 percent for students with limited English proficiency, students in poverty, and foster youth. Once districts and charter schools receive this money, they decide what to do with it.

Sen. Rick Horner, R-Johnston, Nash, Wilson, had some concerns about giving districts money and letting them decide what to do with it.

“I’m quite fearful of throwing the baby out with the bathwater… because when you put that much flexibility on the local level, it really requires a total rethinking of the management teams at the local level, much beyond what we have now in place where our system pretty much dictates what you do, and you don’t have to be innovative to be a superintendent,” he said.

Roza responded, “Our sense is that people rise to the occasion…Over time school systems attract and retain some of their better staff because they’ve trusted them to be part of the decision-making, and we find actually that many folks who think they were comfortable in the old model once they get the new model, they say they have no intention of ever going back.”

Using local funds

The presentation also looked at how best to use local funds to ensure equity in student funding. Because most local funding comes from property taxes, wealthier districts can contribute substantially more tax money to education than poorer districts, creating an unequal playing field for kids. Because of this inequity, some states banned local funding for education entirely before realizing the state had to make up the difference.

Roza advocated for a “tap and tame” approach to local funding: tap into local funding but tame it to ensure it does not produce greater inequity in the system. There are two ways states can do this.

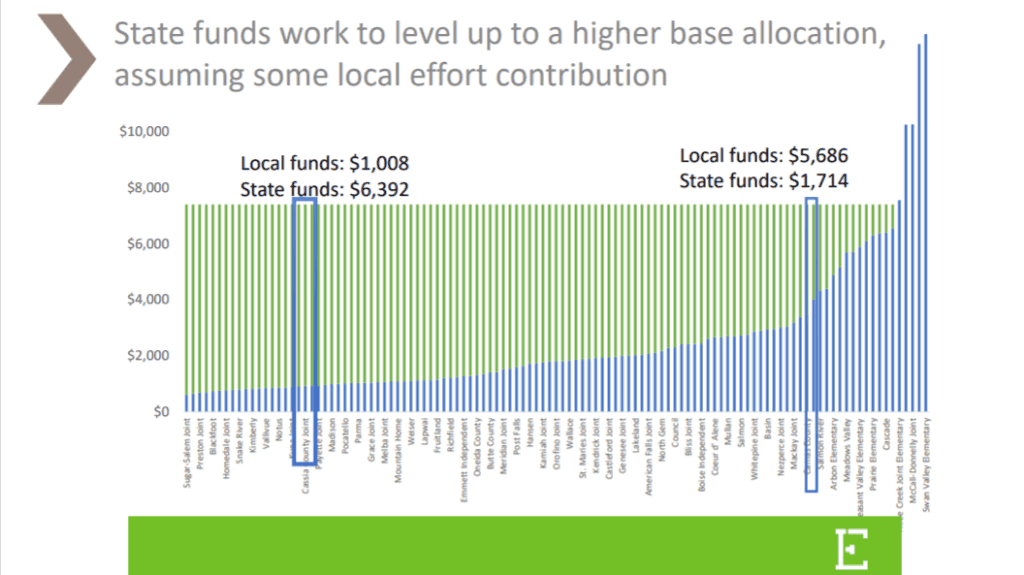

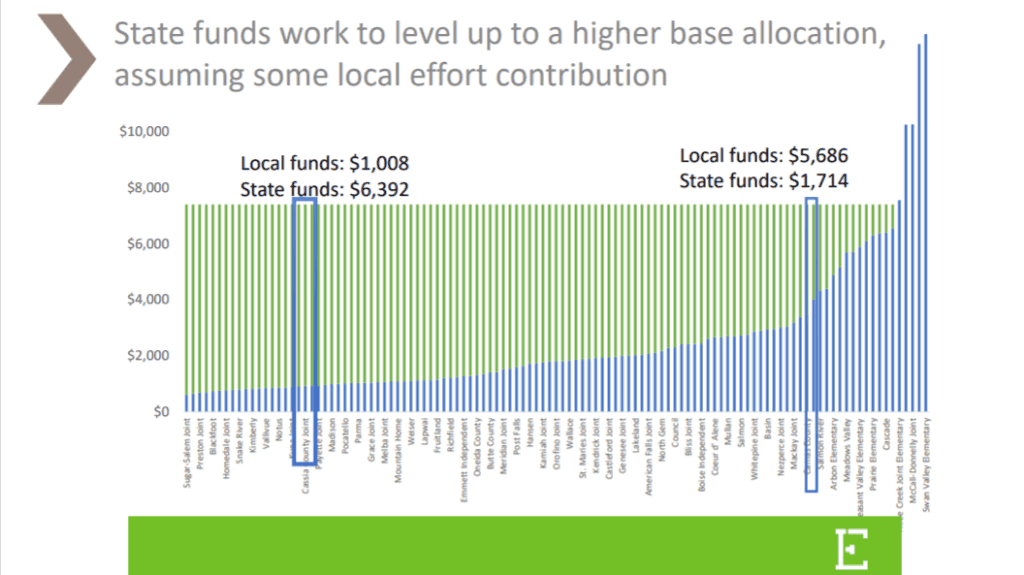

One way is to use state funds to make up the difference between local funds and some established amount per student. For example, let’s say the state decided that all districts should get $8,000 per student. In poorer districts, the local funding may only cover $1,000 so the state kicks in $7,000. However, in wealthier districts, local funding may cover $6,000 and the state only allocates $2,000. Districts that can raise over $8,000 will still have more funding per student, but all districts are at least guaranteed a base amount.

Another option to “tap and tame” local funding is to guarantee local districts a fixed amount per student per tax rate. So the state might guarantee $6,000 per student per one percent tax. If a district raises $1,000 per student from that one percent tax, the state will chip in $5,000. The Urban Institute has a good interactive explainer of local funding options here.

Rep. Horn closed the meeting by reiterating how important it is for the task force to take its time developing a new approach. He stated they will come back after the short session and begin crafting a new formula to be ready by the next long session.