In the 2015-16 school year, North Carolina’s Department of Public Instruction (NCDPI) launched the Proof of Concept Study, a new testing model that, “consist[ed] of three interim assessments administered throughout the school year and a stand-alone summative assessment at the end of the year”[1], with the purpose of the interim assessments described as: “to provide teachers with student-level data to guide instruction”[2]. On July 14, 2016, the State Board of Education approved the extension of NCDPI’s Proof of Concept Study for the 2016-17 school year.

In June, I attended a Test Specifications meeting regarding the Grade 5 Proof of Concept Study wherein an important distinction was made between summative and formative assessment, a distinction that, in my opinion, steers the future of this testing model. In this article, I will not only explain the current model of the Proof of Concept Study and the proposed changes to the model; I will also recommend that the model remains as it is currently designed, a tool to formatively assess student learning, rather than another instrument to fuel the high-stakes testing machine.

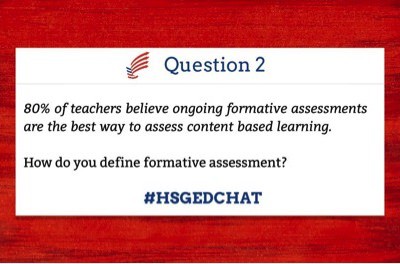

Before we continue, let’s define formative and summative assessment.

Most definitions of summative and formative assessment differ by only one small word. That is, many researchers describe summative assessment as assessment of learning, while formative assessment is assessment for learning. But let’s break that down a bit further.

In their book Understanding School Assessment, Chappuis and Chappuis explain that summative assessment occurs after students have completed learning. Summative assessment is a “status report” that is not intended to inform the classroom teacher about day-to-day instruction nor to help students become better learners. Its purpose is to determine a grade or evaluation, and it is used to direct accountability decisions, including resource and funding allocation for the next teaching cycle.

Conversely, formative assessment occurs during teaching and learning, with ongoing student improvement as the main focus. Formative assessment, “takes advantage of the power of assessment as an instructional tool that promotes learning rather than an event designed solely for the purpose of evaluating and assigning grades”[3].

The purpose and use of formative assessment can be developed even further.

Understanding by Design and Educative Assessment author, Grant Wiggins, explains, “what matters — what makes a formative assessment formative — is whether I have a chance to get and use feedback in a later version of the ‘same’ performance. It’s only formative if it is ongoing; it’s only summative if it is the final chance, the ‘summing up’ of student performance'[4].

Finally, in his book, Transformative Assessment, Popham writes, “we continue to see formative assessment as a way to improve the caliber of still-underway instructional activities and summative assessment as a way to determine the effectiveness of already-completed instructional activities.” Popham adds that formative assessment’s effectiveness lies in the fact that it is not used only by teachers. Teachers use formative assessment results to adjust their ongoing instructional procedures. But more significantly, students use formative assessment results to adjust their own current learning tactics[5].

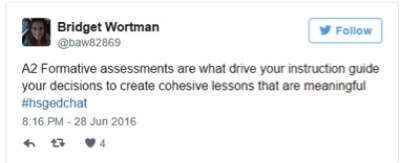

In a recent Twitter chat with NC educators, their comments mirrored the research. When asked to define formative assessment, one educator responded, “formative assessments are what drive [my] instruction; guide [my] decisions to create cohesive lessons that are meaningful.” Another educator added that assessments are formative when they gauge student understanding in order to change instruction. As the chat continued, educators collectively agreed that formative assessment is data collected to inform the teacher and the student of the current learning process in order to increase future student learning.

In short, summative assessment occurs at the end of learning for the purposes of accountability and evaluation, while formative assessment is ongoing assessment that provides opportunities for both teachers and students to make adjustments to the teaching and learning process for the purpose of improving student performance and academic gains.

Now that we’ve differentiated between accepted academic definitions of summative and formative assessment, let’s consider what this means in the context of the Proof of Concept Study.

Currently, the Proof of Concept Study model consists of three interim assessments which are administered throughout the school year. Assessments are paper/pencil and do not exceed 90 minutes in duration, except for students with documented special needs that require accommodations. For each assessment, teachers are given a month-long window to administer the tests. Following the test administration, teachers are provided with individual student reports and class reports that provide a wealth of data to inform instruction. Additionally, teachers are allowed access to the test books for four weeks after test administration to use to guide instruction, review with students, and discuss in parent conferences. At the end of the 2015-16 school year, students participating in the Proof of Concept Study took a modified end-of-grade assessment, which was the traditional end-of-grade assessment without the embedded field-test items.

Teachers, like myself, who participated in the 2015-16 pilot feel as though this current model has been quite successful and helpful in providing students, parents, and teachers the data needed to inform instruction and inform student learning. The current model utilizes the concept of formative assessment in a manner that prepares students for the summative end-of-grade by providing immediate, quality feedback on student performance during the instructional year, and allowing teachers and students the chance to review that performance in order to inform instructional practices and learning tactics to improve student gains on the end of year summative.

In a recent press release announcing the extension of the Proof of Concept Study, State Superintendent June Atkinson stated, “Teachers want interim assessments so that they may address their students’ academic needs when it will have the most impact. Students participating in the study scored higher than those who were not in the study, which reflects the positive benefits of obtaining feedback across the school year and not just at the end.”

It would seem the current model follows the best practices set forth by the concept of formative assessment.

So where’s the concern?

North Carolina has been very focused on teacher accountability as of late, just look to the recent school performance A-F grading system to see evidence of this focus. Accountability, being required to report, explain, or justify the results, is the very purpose of a summative assessment. The NC Ready End-of-Grade summative tests, occur at the end of student learning to summarize student performance and to evaluate teacher effectiveness, to hold teachers accountable. As it stands in the current Proof of Concept model, only the final summative end-of-grade assessment is used as a teacher effectiveness and accountability measure.

Based on the positive feedback and results from this year’s participants, NCDPI and the State Board of Education have approved the continuation of the Proof of Concept Study for the 2016-17 school year. The continued model will follow the same structure, as well as: 1) increase the number of participating schools from 5 percent at each grade level/content area to approximately 15 percent, 2) include a subset of low-performing schools, 3) allow volunteers to participate, preferably one per school district, and 4) require students to take the entire EOG assessment, not the modified version, so that the bank of field test items can be replenished. NCDPI department staff suggested including additional grades in the 2017-18 school year, and then including all grades 3-8, beginning in the 2018-19 school year.

The question is: where will accountability and the measurement of teacher effectiveness overlap as the Proof of Concept model continues to develop?

To address the overlap, there has been talk of changing the model after the 2016-17 school year. Rather than three formative assessments, there would be quarterly or semesterly summative assessments for the purposes of accountability throughout the school year. The end-of-grade would be broken into two or four shorter summative assessments, rather than one long assessment at the end of the year.

What would this mean? And why am I opposed to a revision of the current model?

My primary purpose when I enter the classroom is to help my students grow. Together, with my students, I have 185 days to achieve this purpose. Students have 185 days to achieve grade level academic standards. Students don’t develop in the same way on the same day. While one student will have mastered multi-digit multiplication in second grade, another is still struggling with his eight times tables. We have all year for both students to achieve their potential; I have all year to help both students grow.

The potential revised model would impact my teaching in the following ways:

- Statewide Pacing Guide: All teachers would be required to follow a statewide pacing guide in order to prepare students for the more frequent summative assessments. These more frequent assessments would evaluate both student learning and teacher effectiveness prior to the end of the year. To prepare for these assessments, districts would need to replace current pacing guides, curricular initiatives, and teacher pacing based on student need to ensure students are ready for the state-mandated summative. Whether or not your students are ready to move on to adding fractions, teachers will need to push forward in order to prepare students for the summative test each quarter or mid-year. How likely is it that this will lead to gaps in learning and understanding?

- Teaching to the Test: Once students have demonstrated their learning on a standard during a quarterly or mid-year assessment, they would not be asked to demonstrate their knowledge of that standard on a summative assessment again throughout the school year, which would likely exacerbate the problem of “teaching to the test” and teaching skills in isolation, rather than reinforce scaffolding and spiraling the curriculum. One of the main criticisms of high-stakes summative testing is how those results are used to evaluate teachers and students. In a climate where a teacher’s perceived effectiveness can hinge on whether or not a student demonstrates mastery on a summative assessment, these ineffective and undesirable practices of “teaching to the test” could permeate classrooms and replace quality teaching and learning.

- Mastery of Skills Prior to the End of Grade: This revised model would require students to master grade level standards before the end of the grade, requiring mastery as early as October. Think about this: Students would need to demonstrate mastery of multi-digit multiplication by October. Forget the fact that they need to practice their math facts, and forget the fact that teachers are working with them daily to help them achieve this goal. Forget that they have made tremendous improvement, but that they need a few more weeks of practice to really solidify this concept in their heads. They have until October, and if they can’t demonstrate mastery by then, well, they’ve already been evaluated on that skill, they’ve been told by the state that their scores are not proficient, and they won’t have another chance to demonstrate growth. Then it’s the teacher’s responsibility to communicate that information to the students. It is the teacher who has to tell the students that they’re not proficient even after all that hard work. It is the teacher who has to also tell them that their hard work isn’t over; they must continue working on that skill to demonstrate mastery. Let me know how that goes.

As I said, my purpose in teaching is to help my students grow as learners. When my students join me on the first day in August, I know I have all year to help them achieve their goals. I have all year to help them grow. I have all year, not just the few weeks until their first scheduled Proof of Concept summative assessment in October.

My purpose in writing this article is simple: to encourage North Carolina’s education leaders to recognize the current value of the Proof of Concept model as is, a formative assessment model that provides both teachers and students the opportunity to improve student learning throughout the school year. Moving to a summative model, a model that sums up what a student has learned each quarter, would drastically change the culture of our classrooms. Doing so would create a focus on evaluating students on grade level skills prior to the end of the grade level, increasing testing anxiety in both teachers and students, and forcing teachers to use a fixed mindset rather than a growth mindset when considering student performance. The current formative assessment model uses through-grade assessments for student learning, and isn’t that the purpose of education…for students to learn?

[1] NCDPI, Division of Accountability Services/North Carolina Testing Program. (2015). North Carolina Proof of Concept Study: Grade 5 Mathematics Grade 6 English Language Arts/Reading [Press release]. Www.ncpublicschools.org. Retrieved June 26, 2016, from http://www.ncpublicschools.org/docs/accountability/policyoperations/assessbriefs/pocassessbrief15.pdf [2] NCDPI, Division of Accountability Services/North Carolina Testing Program. (2015, September 1). Proof of Concept Study Frequently Asked Questions [Press release]. Eboard.eboardsolutions.com. Retrieved June 26, 2016, from https://eboard.eboardsolutions.com/Meetings/Attachment.aspx?S=10399&AID=44062&MID=2033 [3] Chappuis, J., & Chappuis, S. (2002). Understanding school assessment: A parent and community guide to helping students learn. Portland, OR: Assessment Training Institute. [4] Wiggins, G. (2011, August 25). Formative vs Summative Assessment- and unthinking policy about them. Retrieved June 28, 2016, from https://grantwiggins.wordpress.com/2011/08/25/formative-vs-summative-assessment-and-unthinking-policy-about-them/ [5] Popham, W. J. (2008). Transformative Assessment. Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

Recommended reading