On June 21, 1996, North Carolina began its charter school experiment with the passage of the Charter Schools Act. Thirty-four charter schools opened in the fall of 1997. The number of charter schools increased in subsequent years until the cap of 100 schools was reached. In 2011, the cap was lifted, and 158 charter schools now operate statewide.

“One of the original goals of the charter school movement, as stated in the authorizing legislation, was to ‘encourage the use of different and innovative teaching methods,'” according to a 2007 report by the nonpartisan N.C. Center for Public Policy Research. “The idea was that charter schools could provide an opportunity for teachers and administrators to try innovations in the classroom which, if successful, could serve as models to be copied in the traditional public schools.”

This is the laboratory function of charter schools.

The Center report found that charter schools statewide were implementing innovative approaches to learning, but the report also found “little evidence that traditional public schools have adopted these innovations on a large-scale basis.”

Twenty years into our charter school experiment, public school districts are reaching out to charter schools and creating opportunities to learn from them.

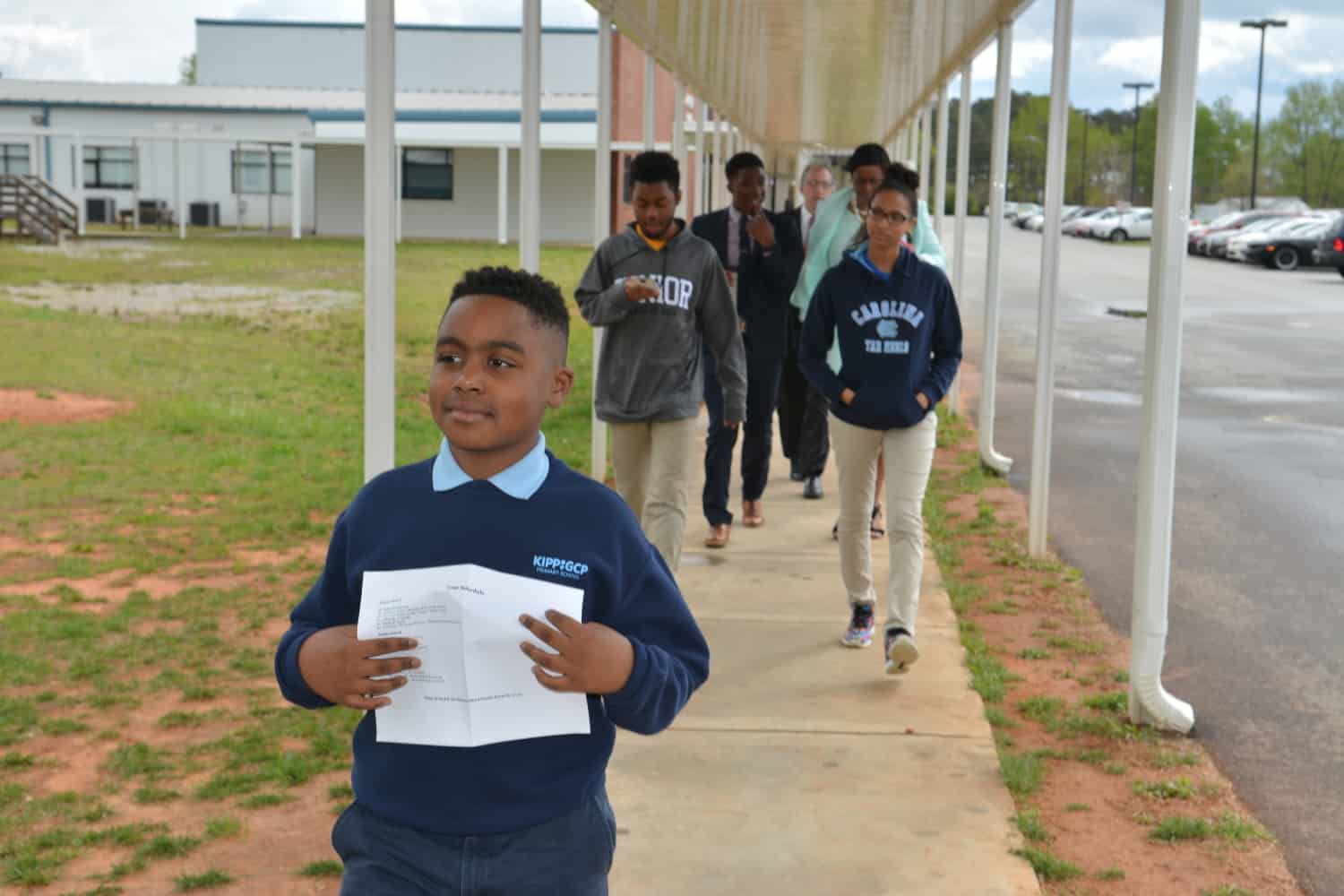

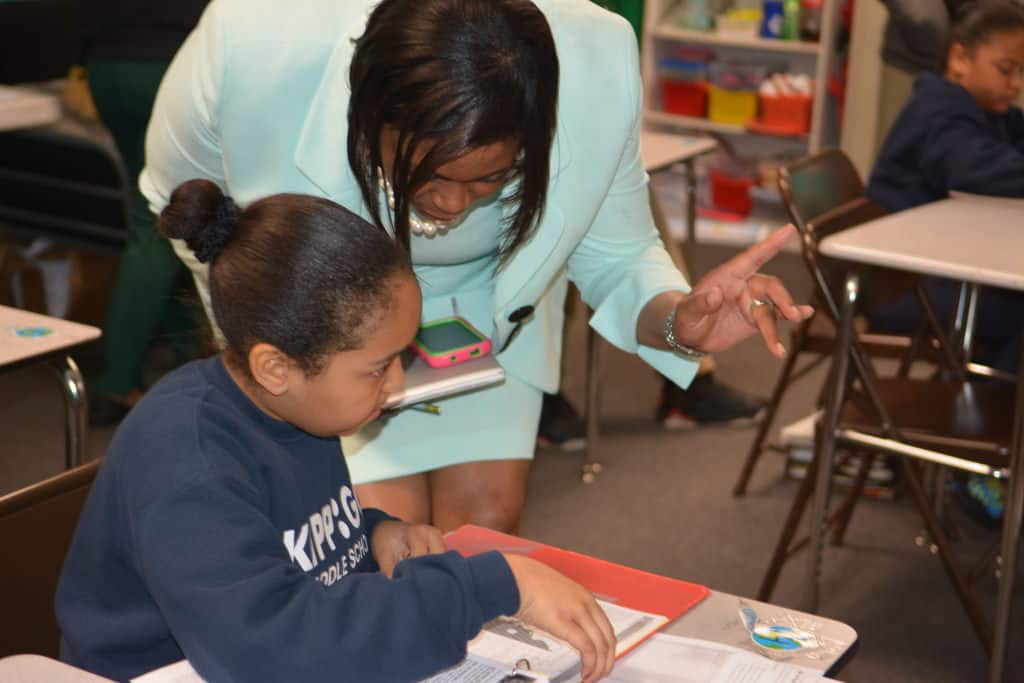

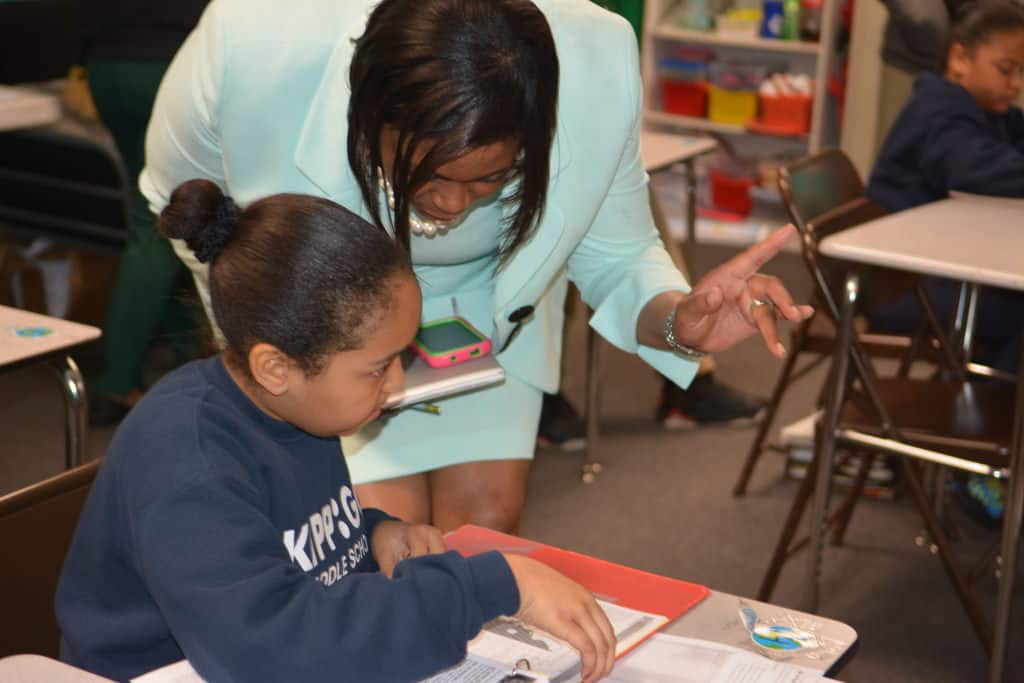

On April 7, 2016, the leadership team of KIPP Gaston shared lessons learned and best practices with the leadership team of the Edgecombe County Public Schools. This was not a stand back and watch kind of visit. From the get go, the district leaders in Edgecombe County were asking questions of students, teachers, and the administrators of this charter school.

The visit included a debrief with Tammi Sutton, the executive director of KIPP Eastern North Carolina; a tour of the KIPP Gaston campus led by students; and an opportunity to hear from and ask questions of teachers and of school leaders.

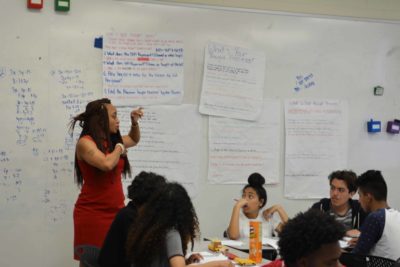

The conversation was earnest and sometimes raw. Unpacking the lessons learned and best practices of KIPP schools doesn’t happen in one morning, but here are some of the takeaways of this visit:

On selecting and retaining great teachers

Sutton said, “We want teachers that come from our community. We want teachers teaching brothers, sisters, and cousins.” School leaders look for teachers that believe the kids can do the work, using a multi-step interview process to determine if applicants really believe in the mission of the school. There is an initial screening, applicants teach a class, receive feedback, and then teach another class to see how well they implement feedback. And then there is an interview. Sutton says, “I want as many touch points as possible that allow me to assess if this teacher will be able to close the achievement gap.”

The leadership team thinks a lot about levers to keep great teachers, intentionally trying to incent a long-term investment in the school and the community.

The role of school leaders

School leaders keep track of how much of their time is spent fostering teaching and learning versus operations and management. KIPP Halifax Principal Marlo Wilkins noted her goal of spending at least 75 percent spent of her time on teaching and learning.

The benefits of K-12 campus

The K-12 campus lends itself to shifting a teacher’s mindset from “handling my kids” to creating a team where everyone is on the same page for all of the kids. Teachers said this increases the capacity for vertical alignment with content expectations shared across grade levels.

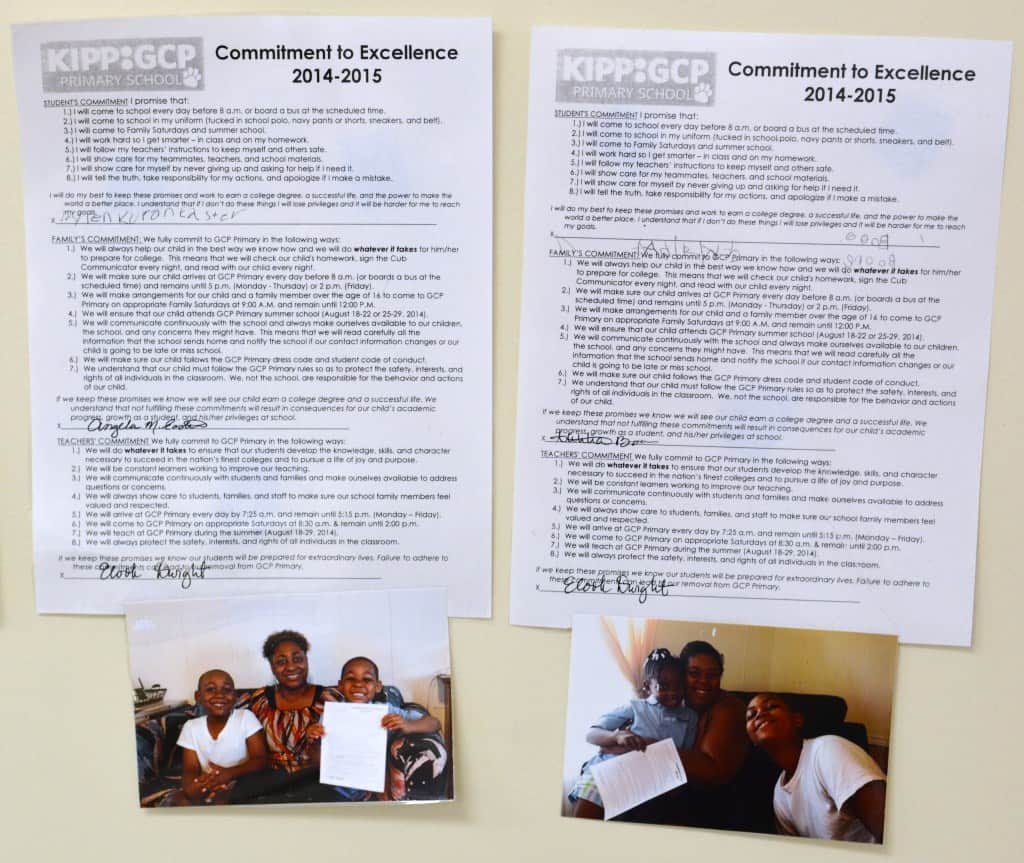

Partnership with families

Sutton says the school has “pretty consistent dialogue with families and kids about where the bar is. It is empowering to know where you are as long as it is coupled with the support to increase achievement.” Primary school parents have to come to “growth card conferences,” where they learn how their “cub” is doing.

The school provides cell phones to teachers for communication with parents and students.

School leaders arrange home visits to meet new students and families.

The Pride includes everyone, and the commitment to each student’s excellence includes the student, the parents, the teachers, and the school leaders.

Increasing learning endurance

The school leaders think a lot about when kids are most exhausted and build in breaks, including a week at Thanksgiving and three-day weekends throughout the school year. The philosophy is work hard/play hard with lots of built in incentives for students.

Here is an example of physical activity built into the school day of students in Kindergarten to keep them focused for longer periods of time.

For teachers, Sutton thinks about “how we are making people feel good about the work,” noting that there are about three low points for teachers during the year, for example the week before spring break.” Creating joy is even more important during those times of the year, says Sutton.

Professional development

Opportunities for professional development are built into the teaching experience, including time on Fridays to discuss shared goals and vertical alignment. But first year teachers also meet once a week, and there are cluster meetings for grade levels.

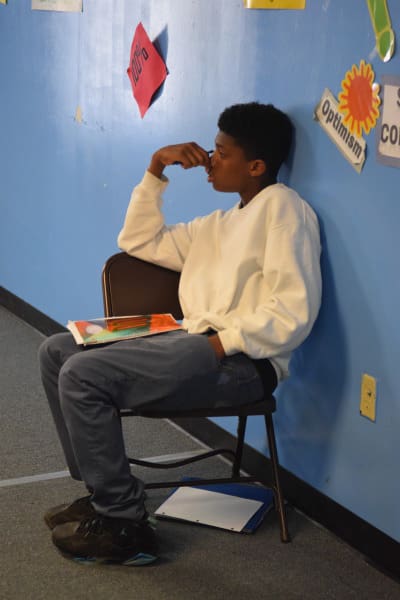

Discipline

Benching is a technique that has been used for middle school students and continues to evolve with the changing needs of the students. Students wear white shirts and sit on the sidelines while they work to earn back their uniform shirt. School leaders needed a “left-hook” that would allow them to keep students in class but also establish the expectations of the community. The concept of benching was easy to implement because the kids understand how benching works on sports teams, she says.

“These behaviors interrupt education and the trajectory of the student,” says a teacher. The school wanted to focus middle school students squarely on the future: HS, college, and life beyond. Benching provided time for reflection, an opportunity to build stronger relationships with students and teachers, and it ends with students addressing their classmates and owning their actions before rejoining their Pride.

As the founding Kindergartners matriculate to the middle school in a few years, school leaders are continuously meeting to discuss how this technique will continue to evolve or devolve.

A teacher is quick to note that teachers own their relationship with the student, and when behavior is a problem, the question is, “What did we do wrong?”

CGI: Cognitively Guided Instruction

CGI is built into the primary school day because the school believes that students need to be equipped with the tools to solve problems at the most advanced level that is age appropriate.

In 8th grade, all kids have the opportunity to take Math I. Many students have support, and some take it again. But all of them take the class.

Building community

Every quarter, classes are jumbled. “As a Pride, we want everyone to get a chance to know each other,” says Sutton.