As North Carolina school districts face the deadline to adopt policies that will limit students’ cellphone use by January, the governor’s Advisory Council for Student Safety and Well-Being met on Nov. 17. The council heard from two school districts about the successes of the cellphone policies they already have in place.

In June, the council released a best practices guide for school cellphone policies and recommended that “North Carolina school systems establish policies that eliminate the use of personal communication devices, including cellphones, from the start to the end of the school day.”

In July, Gov. Josh Stein signed House Bill 959 into law. The law requires school districts and charter schools to, at minimum, adopt policies that “prohibit students from using, displaying, or having a wireless communication device turned on during instructional time.” According to the legislation, school boards must adopt these policies and submit them to the North Carolina Department of Public Instruction by Jan. 1, 2026.

Read more

Chatham and Onslow schools share cellphone policies

In the 2024-25 school year, Chatham County Schools launched a pilot program at six of schools that used Yondr pouches to magnetically seal students’ cellphones and headphones in pouches during school hours. Next year, all middle and high school students in the district will participate in the Yondr pouch program.

According to representatives from Chatham County Schools, the program was an overall success. There were 31% less suspensions in the year the pilot schools implemented the program according to Bradyn Robinson, principal at George Moses Horton Middle, one of the schools in the 2024-25 pilot. Schools also saw a reduction in cyberbullying.

A survey on the Yondr program conducted by the school district found that, out of 66 staff member responses, 53 “agree” or “strongly agree” that the Yondr pouches have “improved student engagement during classes.”

Tracy Fowler, chief of student support services for Chatham County Schools, told the council that the Yondr program is one part of the district’s comprehensive approach to student safety and well-being, and that their goal is to increase student engagement. In addition to the Yondr program, she said their approach includes 12 free weeks of telehealth services through Daybreak Health, internet monitoring technology through Gaggle and ZScaler, and the See Something Say Something anonymous reporting system.

Dr. Randy St.Clair, principal at Seaforth High School, another school in the pilot program, said that the Yondr program is “another tool that teachers have to help create a safe learning environment for our students.”

Lindley Andrew, Chatham County’s 2025-26 beginning teacher of the year and a second-year teacher at George Moses Horton Middle School, added that ensuring students’ internet use is done on school-issued devices helps teachers and administrators flag potentially concerning issues and intervene as necessary.

“If they were previously Googling something on their phone that was maybe of concern and should be filtered to a counselor, now they don’t have a phone, so if they search that in their Chromebook, it does get caught and swept in the right direction,” she said.

While the Yondr program appears to have strong support from teachers and administrators, according to Robinson, the district’s survey results show mixed feelings from parents.

The survey results also show that students are less supportive of the program. Only 77 out of 649 student responses “strongly agree” that the Yondr pouches have improved student engagement during class, and 340 student responses “strongly disagree” that the Yondr program has been successful.

“It’s not that everybody thinks it’s fantastic, but we have seen some of the changes that positively affect our students,” said Robinson.

Fowler told the council that the program costs about $25 per pouch, and that the district paid for the program using their general budget. Each pouch should last about four years, and students are responsible for replacing a lost or damaged pouch. While the Yondr program has worked well for Chatham County Schools and its roughly 9,000 students, it may not be as financially feasible in larger school districts.

Onslow County Schools, for example, serves about three times as many students as Chatham County. Chief Communications Officer Brent Anderson said Onslow County Schools adopted a district-wide cellphone policy in December 2022, but that a handful of schools had cellphone policies in place before then. The reasons for the district’s policy, he said, included an overreliance on technology after COVID-19, an increase in cyberbullying, and high discipline rates.

According to the policy, students “are permitted to possess wireless communication devices on school property so long as the devices are not turned on, used, or displayed during instructional time or as otherwise directed by school rules or school personnel.”

Jacksonville High School is entering the fourth year of its cellphone policy according to Principal Brenda Hermann, who said students must turn off and put away their cellphones during school hours. If a teacher sees a cellphone, the device is taken to the front office where the student’s parent must pick it up at the end of the school day. If a student refuses a teacher’s request to turn in their cellphone, the student’s behavior is considered an act of defiance and is then addressed by an administrator.

Hermann said her school’s policy for students who refuse their teacher’s request is up to three days of out-of-school suspension.

“It’s not really about the phone. It’s about the noncompliance piece, which we’re not going to tolerate,” she said.

Jacksonville High School, the largest school in the county, was in the top 2% in growth for the state last year, according to Hermann. She said she attributes much of the growth to the policy’s impact on student engagement inside and outside of the classroom.

“Nothing was better than going into the cafeteria and seeing kids being kids, right? Talking, engaging, it was loud,” she said.

Alicia Hodal is the principal at Swansboro Middle School, and their policy mirrors Jacksonville High’s. According to Hodal, the school has only had to confiscate 13 cellphones this school year. The school serves 958 students.

![]() Sign up for the EdDaily to start each weekday with the top education news.

Sign up for the EdDaily to start each weekday with the top education news.

Addressing parental concerns

Cellphone policies that remove students’ ability to call or text their parents during the school day have raised concerns for parents. One main reason for their concern is not being able to reach their child during an emergency.

“One of the things our parents brought up in our parent meetings concern was, ‘What happens in an emergency? How do I get a hold of my kid?,’” said Robinson, principal at George Horton Middle. “And the answer was: We don’t want you to.”

Robinson explained that when an emergency happens, it is better for the school to have full control of the situation so that they can reduce the spread of misinformation. Fowler of Chatham County Schools added that the Yondr pouches eliminated layers of unnecessary communication when one of their pilot schools went into lockdown last year, making it easier for the district to enact their emergency response plan.

“What was actually amazing about that is that no information went out by a student. We were able to actually send all of the information from our district office to share with parents that there was a lockdown. And that was so helpful,” she said.

Parents also raise concerns about not being able to conveniently reach their child outside of emergency situations. In response, school leaders at the council meeting said they have introduced other options for students and parents to reach each other during the school day.

Hermann said that her school has a dedicated phone for students in their front office. If a student wants to make a phone call, they are permitted without any questions asked about who they need to call.

The 1:1 Program in Onslow County Schools also gives each student a personal laptop, and students are allowed to email their parents during the day if they need to. Because the devices are district-owned, internet security monitoring systems filter the content of messages.

Advice for successful cellphone policies

Despite their different approaches, Chatham County and Onslow County schools provided similar advice for districts that will adopt cellphone bans in the coming months.

First, presentations suggested it was important for the districts to engage the school community before their policies went into effect. When Chatham County Schools first considered implementing Yondr pouches two years ago, Interim Assistant Superintendent of Academic Services Christopher Poston said district leadership asked teachers and the student advisory council for their thoughts on the idea. District leadership then took the concept to their parent advisory council, allowing parents to interact with and ask questions about the pouches.

Onslow County Schools took a similar approach. While their cellphone policy was adopted by the local school board in December 2022, Anderson said the district decided to wait until the following school year to implement it so that they could take time to communicate with parents how the policy would work.

Second, district representatives agreed that it was important for their policies to be enforced consistently and for teachers and administrators to be on the same page about consequences.

Reflecting on her school’s policy to confiscate phones, Hermann said that “students quickly learned that that’s what that would mean, and they understood it because we enforced it consistently, every day.”

Anderson added that administration’s support for teachers as they enforce the policy is a key part of success — it is important for teachers to know that administrators will support them as they are on the front lines of implementing the policy.

Second-year teacher Andrew, for example, said it was helpful to know that Principal Robinson enforced the policy uniformly and would handle any student who refused to use the Yondr pouch.

“Because they (students) know that that’s the expectation and that across the board at our school, all staff are on the same page, all admins are on the same page, it’s not even a battle,” said Andrew.

Subcommittee meetings on student safety, well-being, and physical health

After the districts’ presentations, the council broke into subcommittee meetings Similar to the council’s September meeting, each subcommittee received presentations from subject matter experts.

The student safety subcommittee, which moved into a closed session, heard from Karen Fairley from the Center for Safer Schools and William Ray of the SERA Project. The student well-being subcommittee received presentations from Stacie Forrest and Rachel Johnson, staff from the North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services.

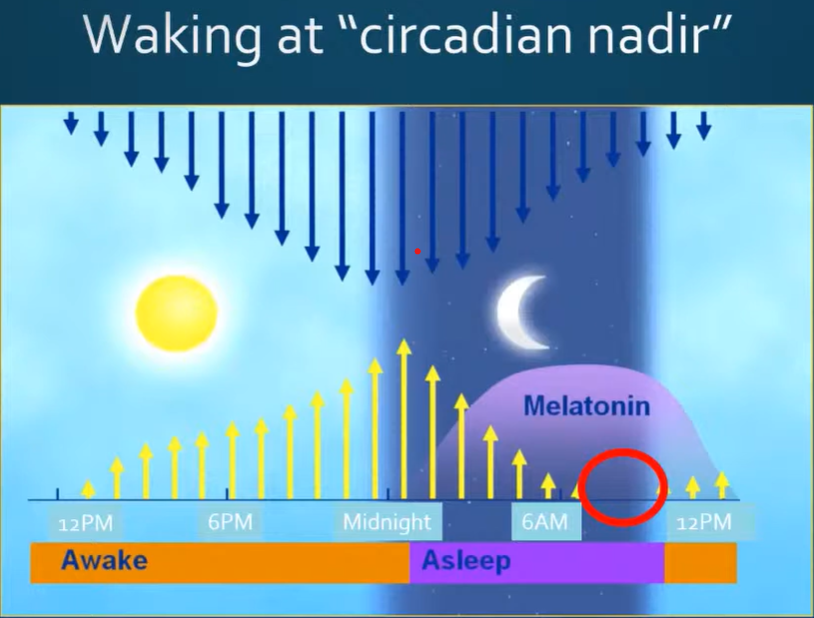

Dr. Sujay Kansagra of Duke University presented to the student physical health subcommittee on the science of adolescent sleep, including the impact of sleep on students’ academic performance, physical health and safety, and mental well-being. His presentation also included discussion on how school policies can hinder students from receiving the recommended amount of nightly sleep.

According to Kansagra’s presentation, research shows that current early school start times are at odds with adolescents’ sleep physiology. By shifting school start times later by 30 minutes, from between 8 a.m. and 8:30 a.m. to between 8:30 a.m. and 9 a.m., research suggests students would benefit from improved emotional, academic, and economic outcomes.

In addition to making schools start later in the morning, Kansagra recommended that schools include sleep as part of student health education or biology classes, decrease students’ homework burden, introduce a staggered exam schedule for core classes, include drowsy driving in driver’s education curricula, and consider buffering early start times by setting boundaries on how late evening school activities can last and how early morning activities may begin.

According to council co-chair William “Billy” Lassiter, deputy secretary at the North Carolina Department of Public Safety, the advisory council will release a video on cellphone policy implementation in December 2025, and in June 2026, the council will submit a final report to Gov. Stein.

The council’s next meeting will be held virtually on Jan. 26, 2026.

Previous agendas and upcoming meeting information can be found here. The council also welcomes public comment from the community on issues related to student physical, social, and emotional well-being through this form.

Recommended reading