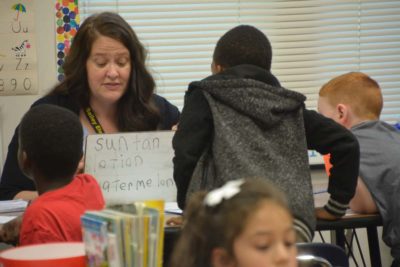

Jennifer George, a kindergarten teacher at Bailey Elementary in Nash County, has taught for more than two decades in various grades and settings, even in a few countries. She says she still has many teacher friends in Canada who are often surprised to hear about the lack of play in her North Carolina classroom: “They can’t believe it.”

George said she tells them: “I have some play stuff that’s hidden in the back, and it really only comes out when it’s a rainy recess or it’s a reward. It’s not part of our regular day. It’s really frowned upon to make it part of our regular day.”

Allowing children to learn through play — a philosophy that is at the heart of pre-K in North Carolina but is lost in kindergarten — would be good for her students, George said. Instead, she has seen an emphasis on increasing academic standards after pre-K throughout the last decade.

“We could meet more in the middle and not have so much of the sitting and testing and writing all the time,” George said.

These differences between pre-K and kindergarten were part of what a group of researchers in a national Early Learning Network found in a study titled “(Mis)Alignment of instructional policy supports in Pre-K and kindergarten: Evidence from rural districts in North Carolina,” published in Early Childhood Research Quarterly this year.

The team, led by UNC-Chapel Hill researcher and professor Lora Cohen-Vogel and funded by the Institute of Education Sciences, talked with principals, early childhood center directors, and district-level administrators from rural North Carolina, asking about the level of alignment between NC Pre-K and the early elementary grades. Across all studied measures — standards, curricula, and assessments — study participants reported that the methods of early childhood education and those of early elementary systems weren’t aligned very well.

Why does this matter? Alignment affects how much difference a pre-K can make in young lives, said Michael Little, one of the researchers on the team and an incoming assistant professor at N.C. State University.

“A lot of this work is motivated by the fact that … pre-K is a really promising intervention,” Little said. “It can help improve kids’ readiness for school and lead to longer-term life outcomes.”

Evaluations of NC Pre-K, the state’s public preschool that targets 4-year-olds from low-income families and other “at-risk” groups, have linked the experience with stronger academic and social outcomes for children.

But those gains can fade in later years, Little said.

“In order for the promising benefits of pre-K to be sustained, the subsequent schooling experiences need to be aligned and coherent to build upon early learning gains,” he said.

A common theme that arose when the researchers interviewed the educators, Little said, is something the research team called the “academic/developmental debate” between early childhood and K-12 environments.

“There’s this gut sense amongst educators in these two different spheres that there is a certain appropriate pedagogical approach that’s unique to their grade,” he said. “And it’s this pre-K/kindergarten divide that’s kind of stuck in between these two worlds.”

In pre-K, Little said, the research team heard that the environment is based on social/emotional learning and learning through play. Students spend most of the school day in centers where they choose what they want to do and how they want to do it.

In kindergarten, the study found, the philosophy changes to focus more on academic outcomes and assessments. Students spend most of the day in desks, being told what to do by teachers.

The study summed up the issue this way:

In short, opinions differ between what is developmentally appropriate in both Pre-K and kindergarten and what an ideal mix between socio-emotional and content-based academic instruction should be. Participants provided consistent characterizations of the current landscape of Pre-K and kindergarten, arguing that Pre-K focuses more on developing students’ non-academic skills, including domains such as self-regulation and interpersonal skills, and kindergarten focuses more on developing students’ academic skills, such as numeracy.

“When we talked to participants, they said, well, the reason there’s misalignment is because there is misalignment,” Little said. “These are totally different grades. The overarching purposes and goals are different, and so we wouldn’t expect to have kind of a seamless alignment because pre-K is what pre-K is and then kindergarten is what kindergarten is.”

But this dichotomy does not have to exist, he said, and some participants recognized this. After all, there is only one year of a child’s life between pre-K and kindergarten. Little said the solution does not have to be completely changing either of them, but finding a common middle.

“You can have academic instruction in pre-K that’s delivered in the context of a developmentally appropriate practice,” he said. “…There’s also avenues for moving forward where academics can be pushed down into pre-K … and also developmentally appropriate practices can be extended up into kindergarten to support social/emotional learning.”

Why are the two grades so different?

So where did this philosophical divide come from? The research paper says “institutional siloing” is part of the reason why educators perceive these two grades so differently, which affects how teachers teach and how children learn.

In North Carolina, pre-K is housed in the Department of Health and Human Services, while K-12 education falls under the Department of Public Instruction. That means different people and bodies oversee the standards, curricula, and assessments. With different governance comes different practices, the paper says.

… A lack of state-level guidance and structures impede two core strategies for developing strong vertical alignment between Pre-K and kindergarten: kindergarten transition practices and data sharing.

The B-3 Interagency Council, acknowledged in the paper and formed in 2017 by the state legislature, is working to bridge that governance gap. The council was tasked with creating a coordinated system of education between early childhood and early elementary. Getting leaders in the same room, Little said, is a step in the right direction.

The research team also found that the alignment strategies mentioned above — “transition practices and data sharing” — vary widely among districts. Some kindergarten teachers get no information about their incoming students, the paper found, including whether they even attended pre-K. Other schools conduct their own versions of pre-entry screeners, which collect different levels of detail on where students are.

Of the students who do attend pre-K, information about their learning and development rarely makes it to the kindergarten teacher. When information from pre-K assessments is shared, the paper says, kindergarten teachers often ignore that data since there are new and different kindergarten assessments to which they must pay attention.

The paper found that having pre-K classrooms in elementary school buildings helps increase both communication and data sharing between pre-K and kindergarten teachers and transition practices throughout the pre-K year. Elementary school principals with pre-K classrooms in their buildings seemed to know more about early childhood development, the paper says. This is a common theme Little has noticed in other research he has done on P-3 alignment, he said.

“I think that school-based pre-K can open doors for much stronger transition practices,” Little said.