EAnne Goodson said she has been in nursing “for forever.” After four decades of working in the field as a licensed practical nurse (LPN), Goodson is back at school to become a registered nurse (RN). Instead of choosing a program in Raleigh, where she lives, Goodson started commuting to Wilson Community College about an hour away.

“This is such a great program,” Goodson said. “So I’m learning from the students and then I’m sharing what wisdom I have.” She said Wilson has been particularly helpful in guiding her through the transition from LPN to RN, accepting credits from her pre-med bachelor’s degree. Goodson is an example of how the college tries to meet students with highly specific needs right where they are, President Tim Wright said.

“It depends on where that student is in his or her life,” Wright said. “Do they need just some skilled-up training? Maybe something we can provide through a 16-week course on our continuing education side of the house? … Or are you someone who needs a full two-year degree, like a paralegal degree? Or are you someone who just needs some portion of a four-year degree?”

The college’s virtual medical center, located on Wilson Medical Center’s campus, provides nursing students like Goodson the chance to practice care on highly-realistic $38,000 mannequins through a 2008 Golden Leaf Foundation grant. Because of the program’s positive outcomes, they’ve added 10 new RN seats this year to enroll 90 students. One of the college’s biggest challenges, said Wright and Wilson’s marketing director Jessica Bailey, is finding ways to reach different audiences and showing them which of Wilson’s opportunities is right for them.

“Even growing up here, you don’t realize necessarily what the community college has to offer,” Bailey said. “I think it’s important, especially now, to get that information out to the community.”

The community college has tried everything — a TV commercial, billboards along the highway, social media targeting, and re-designed physical mailers. Bailey recently took a “lifestyle analysis” of those living in the region to try to get to better know the community’s needs, from educational attainment levels to preferred information sources. Wright said reaching the right individuals with the right knowledge is often just the first part of this challenge.

“Our students on average, compared to university students, are older, they’re more likely to have minor children, they’re more likely to have financial resource challenges, they’re more likely to work,” Wright said. “The ones who do work tend to work more hours per week. So, on average, our students have more life happening to them. When you go out and find the people, when your marketing is successful …. then, sometimes, the work has only just begun.”

Wright said those obstacles make it harder for adults to return to school who would benefit from doing so. With Wilson’s unemployment rate at 7.3 percent in 2017, compared to the statewide 4.6 percent, Wright acknowledges an opportunity for the community college to give individuals and the entire community a better future.

“There are lots of unemployed people who could benefit, but it isn’t nearly as simple as it sounds,” Wright said. Wilson began a wellness campaign last year to try to help students be prepared to take advantage of the available educational opportunities. The college opened a food pantry for students free of charge. In the first semester, 150 students were served. That is 10 percent of the college’s curriculum students. Wilson has also done a clothing drive to provide professional attire to students.

“We have folks who are stuck in their life situation,” Wright said. “Life is very very sticky for folks who are unemployed. And you’ve got to help pry some of those challenges off of them, like child care and transportation and food insecurity.”

Aesthetics also matter, Wright said. The community college is located in downtown Wilson, and is one of the only community colleges still in its original 1950s building. The campus was one of a handful of original “industrial education centers” before community colleges came to fruition across the state. Across the street is an abandoned factory building.

“We’re an I-95, 301 town. And what happens on I-95, 301 towns is, in the last 50 years, the money has moved from the 301 side to the I-95 side. That’s up and down the state, that’s what’s happened. And we’re on the 301 side because that’s where the industry was and that was our identity in 1958.”

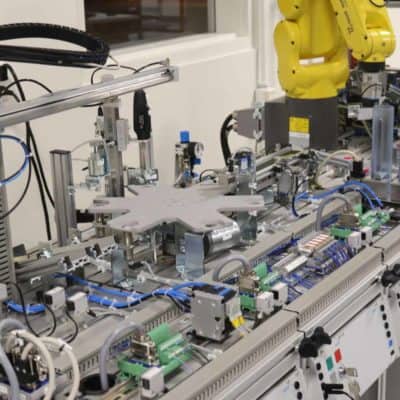

But that dynamic is one that the college is taking advantage of: its applied engineering lab was a 1960s Nissan dealership. A new facility down the road, which will house the college’s Small Business Center by the end of the year, used to be a Ford dealership.

This past year, the Small Business Center created 34 new local businesses. The center helps entrepreneurs from the very beginning with business plans to guide them through opening and the first couple years of operation. In a small town, that’s a huge impact, Wright said.

And that’s just the beginning of the college’s impact on the area. About half of the nurses in the community went through Wilson Community College’s program, Wright said. Almost every police officer, firefighter, and EMT worker was trained at Wilson. The college holds adult high school classes for those looking to complete a GED and supports English-language learners. The college is constantly in communication with industry to ask what skills workers need. In the last year, the college has done half a dozen specialized training workshops for specific companies.

“If you took Wilson Community College out of Wilson County, Wilson County would be a fundamentally different place,” Wright said. “It wouldn’t be just a little different. It would be really different. And poorer, in all meanings of the word.”

Recommended reading