|

|

“As time has evolved, and finances have become a little bit tighter, it’s been a little bit more difficult to justify to my husband the expenses, as far as why we do what we do.”

Melissa Johnson, Business Management/Information Systems Instructor at Isothermal Community College

Melissa Johnson is part of the North Carolina community college system – a system that continually ranks in the bottom 10 states nationally for faculty pay.

Because of this, North Carolina community colleges are in what some are calling a crisis. Despite being an issue for years, the pandemic has exacerbated the need for state funding to support salary increases among community college personnel.

Community colleges in North Carolina are on the frontlines of the state’s economic recovery effort – supplying a credentialed workforce that will boost the economy and help the state reach its 2 million by 2030 attainment goal. However, community college presidents and administrators say low pay is making it difficult to recruit and retain the employees needed to meet this goal.

“Pay increases are critical,” said Mark Kinlaw, president of Rockingham Community College. “The community college system, historically, has always been looked to as the economic driver of the state because we produce people that are ready to go to work … that’s going to be more important coming out of the pandemic. The only way we’re going to be able to significantly do that and be impactful is to have salaries that are competitive that attract faculty and staff to our system that can help make that happen.”

For the past two years, the North Carolina Community College System has asked the legislature for funding to increase employee pay. In 2019, disagreements between the General Assembly and the governor meant that no state budget was approved and the community college system didn’t receive funding for pay raises as a result.

This year, the system is asking for a 5% raise for community college employees.

“A minimum of a 5% pay increase for community college staff and faculty will be critical to ensure our colleges retain and attract world-class talent. An increase higher than 5% would enhance our progress toward a competitive salary scale,” said Thomas Stith, president of the North Carolina Community College System.

The governor’s budget includes a 7.5% raise over the next two years and a one-time $2,000 bonus for those employed on April 1, 2021. However, any hopes for a community college pay raise will depend on the budget released by the Senate and House in the coming weeks, and whether the legislature and governor can come to an agreement.

In the bottom 10

Since 2006, faculty salaries at North Carolina community colleges have ranked among the bottom 10 states for every year but one. In the southeast region, the worst paying region in the country, North Carolina almost always ranks in the bottom half or bottom third.

“The third-largest system should not be at the bottom 10 at any given time,” said David Shockley, president of Surry Community College.

In 2017-18, the latest year for which the Southern Regional Education Board has published data, the average full-time community college instructor in North Carolina earned $49,549, which was less than the corresponding salaries paid in all but seven states.

Even within the state, faculty pay at North Carolina community colleges ranks below that of their educator peers. At four-year public universities, faculty pay ranks 24th in the nation. For K-12, teacher pay ranks 33rd in the nation.

Challenges of recruiting and retaining community college faculty and staff

Leaders of North Carolina community colleges see the ripple effects of low pay across their campuses.

Rose Moon, director of human resources at Caldwell Community College and Technical Institute, said attracting candidates continues to be a problem.

“We’ve posted nursing instructor positions 27 times in the past 10 years and received few applicants each time,” she said.

According to Moon, low pay makes it difficult for community colleges to compete with the private sector. The same is true for staff hires, she said, particularly in the information technology department.

“The private sector jobs, in some cases, pay more than double the ceiling of our salary range,” Moon said.

And it’s not just attracting candidates. Many times the challenge is keeping current employees.

Chris English, president of Southeastern Community College, said he has struggled to compete with the private sectors for years.

“When I worked at Blue Ridge Community College, I had a fantastic automotive instructor. I mean, Matt was top-notch. He had a 10-year career, and Chrysler corporate came calling and he went to making six figures. There’s no way I could compete with that,” English said.

In the span of a year and a half, Kinlaw lost three welding instructors to the private sector.

Shockley lost 28 employees from 2020-2021.

“I’ve been in the system for 26 years. I’ve never seen what I’m going through at Surry Community College … Money was a factor in each of those decisions.”

David Shockley, president of Surry Community College

To make ends meet, some community college employees have to work multiple jobs. Jeff Cox, president of Wilkes Community College, was recently confronted with this reality in a checkout line.

“I was taken aback when I got to the checkout line and it was one of my employees,” Cox said.

“It just struck me that she’s not doing that for fun because she’s bored on the weekends. She’s having to pick up that income because she needs it.”

Jeff Cox, president of Wilkes Community College

In addition to the private sector, community colleges also lose employees to the K-12 districts in their service areas, presidents said.

Cox explained that because community college faculty typically are nine-month employees whereas K-12 teachers are typically 10-month employees, that extra month means that if community college faculty and K-12 teachers have the same salary, K-12 teachers are starting with a pay advantage over community college faculty.

But it’s not just that.

In the past five years, the General Assembly passed and Gov. Roy Cooper signed into law pay increases for K-12 teachers. In 2015, beginning teacher pay was set at $35,000. In 2016, teacher pay increased by an average of 4.7%. During the long session in 2017, the final budget raised teachers’ salaries an average of 3.3% in the first year of the biennium and 9.6% over both years. By 2018, lawmakers budgeted a 6.5% average pay increase for teachers. In 2020, teachers received a one-time $350 bonus but no pay raise.

Community college faculty and staff have not seen those same raises, even when they teach K-12 students. Through the state’s Career and College Promise program, high school students can take community college classes. As this option has become more popular, many community college faculty are teaching 9th through 12th grade students.

“When K-12 teachers get higher bonuses, it’s noticed,” said Dawn Dixon, associate vice president of university studies and educational technologies at Johnston Community College, “especially when we teach 9-12th graders with no additional compensation.”

“I haven’t heard a single person in the community college system begrudge the public school teachers [regarding pay raises]. But I have heard a lot of us saying, when is it our turn?”

David Shockley, president of Surry Community College

Feeling valued

When it comes down to it, it’s about feeling valued, community college leaders said.

“It’s an emotional issue,” said Shockley, “that emotional recognition that comes along with a raise, an appreciable raise, that says, we value what you do.”

For Johnson, a community college instructor for over 20 years, a pay increase would make her feel that she and her colleagues are valued.

“It is very disheartening when you do more and more and more, and you put your heart, you put your soul, you sacrifice time with your family, to do for others,” Johnson said.

There are thousands of people like Johnson all across the 58 community colleges.

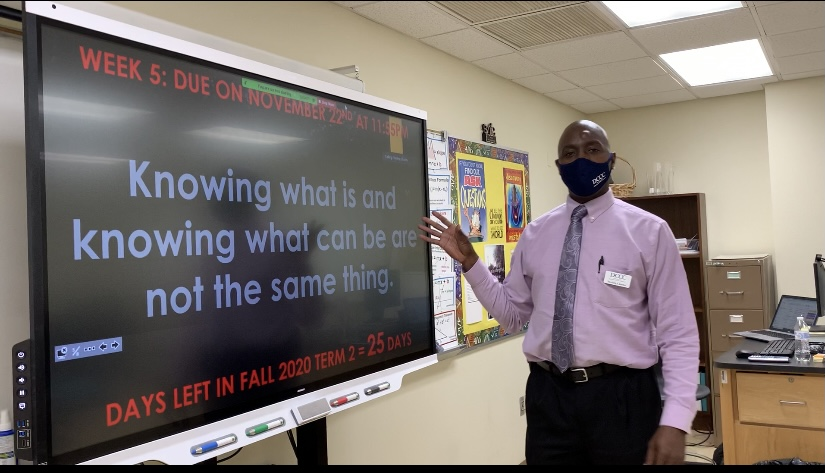

Sterling Charles, transition math instructor at Davidson County Community College. Emily Thomas/EducationNC

Brian Wurst, instructor in the Professional Crafts department at Haywood Community College. Alli Lindenberg/EducationNC

“We’ve got a tremendously dedicated group of people who love what they’re doing,” said Cox.

“And while nobody goes into education to get rich, you shouldn’t have to take a vow of poverty to serve in one of our community colleges.”

Jeff Cox, president of Wilkes Community College

It’s not just faculty, presidents pointed out.

“Oftentimes we talk about faculty. And I think quite honestly, it’s because it garners more attention in the General Assembly,” Shockley said. “They talk about teacher pay, you talk about faculty – because I think it grabs attention. But it is a mistake to leave out the staff, because our staff represents half of our employees here … They are as critical to our mission as what goes on in the classroom.”

What’s next?

At a recent State Board of Community Colleges meeting, Kandi Dietemeyer, president of Central Piedmont Community College, made a plea to lawmakers to remember community college faculty and staff:

“Let us not forget, and let us keep reminding those who will stroke the pen in the General Assembly, that this incredible talent and those thousands of graduates would not be possible, or the hope for our great state, if it were not for the incredible talent and really the dedication, hard work, professionalism, passion, and service of the best faculty and staff in the nation.”

Kandi Deitemeyer, president of Central Piedmont Community College

Community college faculty and staff will soon know whether that plea has been answered. The Senate and House are expected to release their budgets soon, and then they have to work out any differences between them before it can go to the governor’s desk. Whether Cooper will sign it remains to be seen.

And even if the community college system does receive funding for pay increases, a one-time raise won’t solve the problem, said Kinlaw.

“It’s going to take years to get us where we need to be,” Kinlaw said. “There has got to be a commitment over a long period of time.”

Editor’s note: Emily Thomas is currently an adjunct instructor at Caldwell Community College and Technical Institute.