|

|

This article was originally published in the N.C. Tribune.

By and large, the road to the greatest places of childhood need runs Down East, according to an advocacy group for the state’s schools.

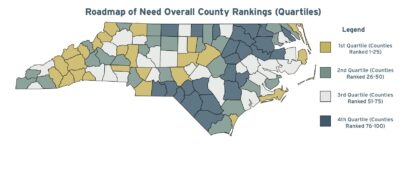

The Public School Forum of North Carolina recently updated its “Roadmap of Need,” which sizes the state’s 100 counties on how well or poorly they do on “20 indicators of wellness” it believes necessary for children to succeed.

You don’t have to be Carnac the Magnificent to guess that the forum’s assessment of the worst-off counties correlates with Tier 1 of the state Department of Commerce’s tier rankings. Such differences as there are mostly have to do with the forum’s use of quartiles to group the counties into groups of 25. Not for them the tier system’s 20-40-40 split.

So it’s no surprise to find a big swathe of bottom-quartile counties running from Northampton County by the Virginia border south to Duplin County. Most of the rest are along the South Carolina border, from Anson County near Charlotte to Columbus and Bladen counties near Wilmington.

What’s more interesting, to me at least, are the three outliers along the Virginia border, Rockingham, Person and Vance counties, plus the big group of top-quartile counties out west in a part of the state that’s generally in Commerce’s Tier 2 listing of economically mid-level counties.

The three border counties also share proximity to the state’s major urban areas, so they lag even though they in theory should be getting some benefit from the cities’ economic gravity. Yet Rockingham ranks 80th in the forum ranking, Person 79th and Vance County 93rd.

Out west, while it’s hardly shocking to see Buncombe County (ranked 6th) in the top quartile, there are good showings by Jackson (22nd), Haywood (15th), Madison (10th), Yancey (23rd), Polk (1st) and Henderson (16th) counties.

Looking at Polk’s indicators, it sticks out that their schools are turning in good eighth-grade math and third-grade reading scores (sixth- and second-best in the state, respectively.)

I’m not sure I buy the reported 0.00% licensed-teacher vacancy rate for the 2021-22 school year (low’s one thing, but zero invites skepticism). But Polk’s doing well in a lot of arenas.

Its overdose-death rate (10.23 per 100,000 of population) is the second-lowest in the state, and it’s got way more school counselors to per student than is the norm across the state (one for every 228 students, good for a seventh-place rank on that measure.) A lot of its other measures are in the lower reaches of top-quartile or thereabouts, and none stick out for being way below average.

One other thing: Polk’s county commissioners are willing to invest a bit in their schools. Local per-pupil spending in 2021-22 was $3,341, the 21st highest in the state and $882 above the state average.

To look at the flip side, I’ll take Vance County, for familiarity’s sake if nothing else.

Not all of Vance’s individual-indicator ranks are on the wrong side of 50th. It has a relatively low suicide rate (5.12 per 100,000 people, second-lowest in the state as of 2020) and a good number of school counselors (one for every 273 students, good for 16th).

For pretty much everything else, though, there’s a lot of bad. Teen pregnancy (43.9 per 1,000, the 94th-worst rate in the state), juvenile detention admissions (3.2 per 1,000 youth, ranked 93rd), teacher vacancies (12.8%, ranked 97th) and third-grade reading proficiency (22.6%, ranked 98th) all stand out here.

And the county doesn’t really invest in its schools — the forum reports the local per-pupil as $1,085 (ranked 94th). I’m not sure I buy that number (you’ll find different ones elsewhere, and the Vance-only report I linked has a couple of typos), but I do buy the relative positioning.

Now, one might ask whether the low per-pupil is a function of ability to pay or willingness to pay, and I’d say the answer is “yes.” Finance-wise, Vance has a lot of problems, including a weak tax base, already high tax rates, and relatively low per-capita income. Not for nothing is its school system a Leandro plaintiff.

But it also has quite a few charter and private schools handy to siphon students from the county K-12 system, and with them the willingness of voters and elected officials to pony up for the latter. You’ll also find the relevant political split on the county commissioners isn’t the one between Democrats and Republicans (you find both) but between bulls and bears — folks who believe the county has a brighter future, and others who aren’t convinced. The bulls are willing at least sometimes to spend money; the bears, not so much.