Question:

What do Bob Scott, Pat Taylor, Jim Hunt, Jimmy Green, Bob Jordan, Jim Gardner, Dennis Wicker, Bev Perdue, and Walter Dalton have in common?

Answer:

Over the past 50 years, each served as North Carolina’s lieutenant governor and subsequently ran for governor. Of these nine, three won the governorship: Scott for one term, Hunt for four terms, Perdue for one term.

Campaigns for lieutenant governor tend to take place in a niche of the political landscape dominated by the more flashy contests for president, governor, and U.S. Senator. But the recent history of the lieutenant governor’s office serving as a launching pad for a quest for higher office helps to frame the significance of the choices North Carolina voters will begin to make in the March 15 primary.

On that day, Democrats will select among four candidates for the nomination to challenge Republican incumbent Lt. Gov. Dan Forest. While seeking re-election, it’s considered impolitic for a candidate to acknowledge looking ahead to another campaign beyond the current race. Still, Forest’s high-visibility as lieutenant governor suggests that he could well follow the pattern set by nine of his predecessors since 1968.

In the general election four years ago, Forest won the office with 50.1 percent of the nearly 4.4 million votes cast. He defeated Democrat Linda Coleman, a veteran of state government, by fewer than 7,000 votes. The fact that Coleman and Forest each received more than 2.18 million votes in 2012 says less about their own visibility among voters at that time – and more about how highly competitive and closely divided North Carolina has become between Democrats and Republicans.

Now, Coleman is running again for the Democratic nomination. The fact that millions of voters have seen her name on a previous ballot surely gives her an advantage in 2016. Her stiffest competition comes from Holly Jones, a veteran of local government in Buncombe County. Ronald Newton of Durham and Robert Wilson of Cary are also running in the Democratic primary but appear distinct underdogs.

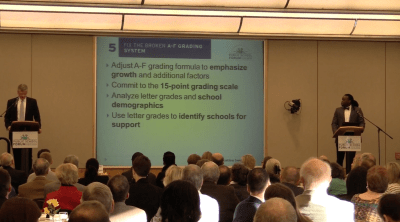

In addition to considering Forest and these Democratic candidates as potential aspirants for governor, voters also should know that the lieutenant governor sits on the state Board of Education. With his questioning of Common Core standards and his advocacy of charter schools and digital technology, Forest has demonstrated how the lieutenant governor can influence education policy.

You won’t find much on education on the campaign websites of Coleman and Jones. Still, it’s evident that both Democrats stand against the sharp shifts in education policy enacted by the Republican legislative majority since 2010. In newspaper Q-and-A features, both Coleman and Jones have put public education at the top of their list of priorities, advocating higher teacher pay and reversing budget trends that have led to a decline in per pupil spending in North Carolina public schools.

Jones, who is 53, has had a local government career consisting of service on the Asheville City Council and the Buncombe County Commissioners. Though she has not been part of the education debate in the state capital, she showed knowledge and agility in an EdNC interview for a podcast.

Jones described termination of the Teaching Fellows a “fatal mistake” and the A-through-F grading of schools as “damaging.” She called public schools part of the “fabric of democracy,” and added, “My hope is that fabric will remain together and not unravel.”

Coleman, who is 66, served three terms in the state House, representing a Wake County district, as well as chair of the Wake Board of Commissioners. In the Perdue administration, she was director of the Office of State Personnel. Coleman (who has not been available for an EdNC interview) has long advocated for state employees and assails “the tone-deaf Republican majority’s failed policies (that) leave the middle class slipping behind.”

Neither Coleman nor Jones has enough campaign funding to mount a strong media advertising campaign. They depend on intra-party organizing, endorsements from newspapers, and word-of-mouth from political allies and personal friends. Still, the Coleman vs. Jones contest could have ripple effects not usually considered by voters in the standard low-visibility down-ballot election – with implications for the state’s sweeping education debate and for potential candidacies for governor in 2020 and beyond.