Over the next five years, 15 N.C. Community Colleges will implement Boost, a replication of The City University of New York (CUNY) Accelerated Study in Associate Programs (ASAP), also called CUNY ASAP. The program is designed to help students earn their associate degree on time by providing wraparound supports that address common barriers outside of the classroom.

Multiple rigorous evaluations of CUNY ASAP have found large, statistically significant increases in college graduation rates for participating students, propelling the program to national acclaim and spurring replications in nine other states.

Read more about Boost

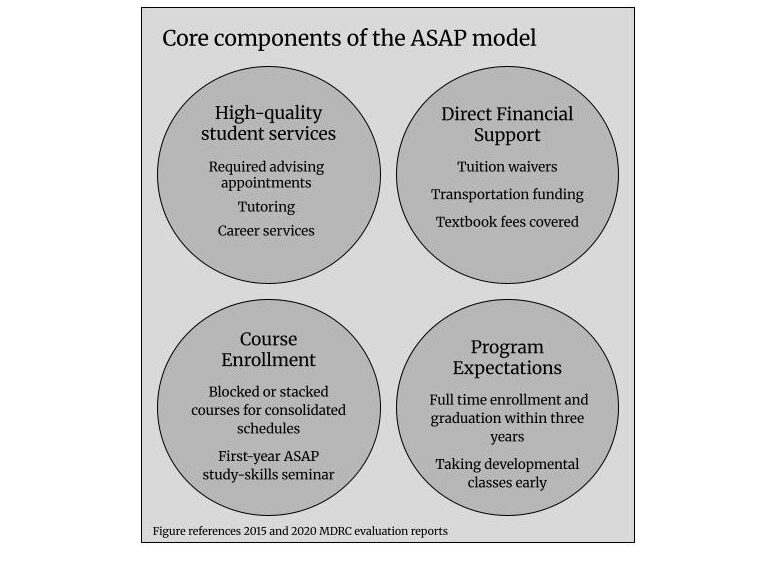

The CUNY ASAP model includes high-quality student services, direct financial support, course enrollment, and program expectations that facilitate movement through the program — but many consider the heart of the model to be high-touch, personalized student advising, with the same adviser, from enrollment to graduation.

In a 2015 evaluation of the program by MDRC, CUNY ASAP students shared that “advisers were important to their academic success” and “advisement was one of the most helpful program components.”

“The no. 1 thing students came to the (CUNY ASAP) program for was the financial benefits. However, when they left, the one thing they spoke most about was the advising experience. I think that says everything,” said Matthew Eckhoff, former ASAP LaGuardia director and current Boost director at Alamance Community College.

For community college leaders interested in the model, Christine Brongniart, university executive director of CUNY ASAP, said, “advisement is the place to invest.”

But what sets the model’s approach to advising apart? As leaders of Boost programs and others working on student services at community colleges consider how to best support students, evaluations of the CUNY ASAP program and learnings from the CUNY ASAP National Replication Collaborative offer insights into the approach.

Lower student-to-adviser ratios

The National Academic Advising Association (NAAA) estimates that the national median caseload for full-time advisers at two-year colleges is 441 students per adviser.

The CUNY ASAP model uses much lower student-to-adviser ratios, allowing advisers to provide more personalized and timely support. In the 2015 MDRC evaluation of the program, advisers had caseloads of 60 to 80 students, compared to the typical caseloads at the three colleges in the study, where caseloads ranged from 600 to 1,500 students.

In the Boost program, the typical ratio is 150 students per adviser, with lower ratios for colleges in a consortia.

Dedicated adviser from enrollment to graduation

Students are assigned to the same adviser throughout their time in the program, allowing them to build a deeper relationship over time.

“The hope is that there’s sort of mutual accountability and mutual responsibility for ensuring that the student moves along within the program,” said Lesley Leppert, senior university director of academic advising initiatives at CUNY.

![]() Sign up for Awake58, our newsletter on all things community college.

Sign up for Awake58, our newsletter on all things community college.

Required advising sessions, triaged by need

During the 2015 MDRC evaluation of CUNY ASAP, all students were required to meet with their adviser in person twice per month, resulting in a much higher frequency of student-adviser interactions compared to the typical community college student. Students in CUNY ASAP reported an average of 21.1 contacts with an adviser in their first semester, compared to control group students who reported an average of 3.7 contacts with their adviser in their first semester.

“In a lot of institutions, advisement is not required, so a student will come in when they have something to share with an adviser — but it’s flipped,” said Leppert of CUNY ASAP. “We are consistently reaching out, we are being proactive, we’re asking questions of every student.”

As CUNY ASAP has evolved over time, program leaders developed a triaged approach to assigning advising engagement requirements.

Now, students are assigned to a tier of support — high, medium, or low — based on their assessed level of need, which considers academics, personal resiliency, and participation with program requirements, according to Leppert. This tier of support then determines how many times, and in what format, they must engage with their adviser each semester.

“This way, the advisers can dedicate more time to those students who may need more consistent, and more frequent, individualized support,” said Leppert.

For example, a “low” support student may be able to attend a large workshop to fulfill their requirements, whereas a “high” support student may be required to attend more small group and individual meetings to ensure advisers have dedicated time to address the challenges they are facing.

There is also a separate tier of support assigned to new students, which is focused on building engagement with the program through group activities, workshops, and other campus events.

“We’re able to now really support the new and high support students in the way that they need to be supported, and this creates space on the caseload to do so, because mathematically, it’s just not possible to see 150 students, two times a month, meaningfully,” said Ancy Skaria-Lopez, director of data strategies and evaluation for CUNY ASAP.

To incentivize students to meet their adviser engagement requirements, CUNY ASAP offers financial stipends. In the 2015 MDRC evaluation, students received free MetroCards for the subway if they met all adviser engagement requirements. Under the Boost program, students receive a $100 stipend each month for meeting their adviser’s engagement requirements.

Comprehensive, personalized advising

Advising in the CUNY ASAP model is about more than helping students navigate their academic journey — it also addresses social and interpersonal challenges, career planning, transfer planning, and more. The goal is to help students mediate and solve challenges, including those that arise outside of the classroom, to keep them enrolled and on-track for graduation.

According to Leppert, this advising approach is rooted in the developmental model of academic advising, which focuses on working with students over time to achieve educational, career, and personal goals, with the student playing a role as an active partner taking on shared responsibility. As the program has grown, Leppert said CUNY ASAP has incorporated more contemporary advising approaches, including asset or strengths-based advising, trauma-informed advising, and narrative theory, “to ensure that they’re able to meet every student where they’re at and work with them in the best way.”

In the 2015 MDRC evaluation of the program, students in CUNY ASAP reported discussing an average of 7.5 topics with their adviser, compared to 5.1 topics for students in the control group. Some topics, like course selection and major, were reported at similarly high rates amongst CUNY ASAP and control group students. Other topics, including internships and job opportunities, were reported at least twice as often among CUNY ASAP participants compared to the control group. And, CUNY ASAP students were much more likely to report discussing personal matters than the control group, at 49% compared to 17%.

Although these outcomes were nonexperimental, “these gaps are large enough to imply that ASAP students’ advising experiences had more depth and breadth than those of students not in ASAP,” reads the evaluation.

Leppert credits the trusting relationships that CUNY ASAP students build with their adviser as the reason they are more likely to discuss personal matters, a sentiment echoed by Skaria-Lopez, who previously worked as a CUNY ASAP adviser.

“By the second semester, because that relationship is built and they (students) have that one person to go to, that’s when they will be talking about the various challenges they’re going through in their life,” said Skaria-Lopez. “And so you have to make referrals when you need to and be very skilled in knowing what’s available on campus in terms of resources.”

To help guide how advisers spend time with students, CUNY ASAP provides an adviser handbook that outlines objectives and priority actions by semester and by month. For example, at the start of a student’s first semester, advisers are encouraged to discuss program requirements, align on expectations for communication and appointment scheduling, and confirm financial aid awards. By the student’s second semester, advisers are encouraged to align the student’s academic pathway to their career goals, provide referrals to needed support services, and discuss summer internship opportunities.

Within this framework, Skaria-Lopez said that advisers personalize their support based on each student’s needs. For example, an advising session for a STEM student might focus on career planning and sequencing of courses to ensure they progress toward on-time graduation. For a student that is facing basic needs insecurities, such as being unhoused, an advising session may focus on connecting them to supportive resources such as Single Stop.

CUNY ASAP also places an emphasis on ensuring advising and career planning are connected, according to Skaria-Lopez.

“I think if that’s (career) not discussed at the beginning, then it becomes siloed, like, ‘Go to the career department to talk about career — this is advising,’ but we really have to bring them together,” she said.

Advisers are encouraged to discuss career goals and transfer planning with students from the very beginning to ensure students can move on to the next step in their career or academic journey.

“Having those types of conversations is really, super important — because I think that’s why a lot of our students are coming: for upward mobility,” said Skaria-Lopez.

Recommended reading