Editor’s note: This article was originally published by North Carolina State University’s College of Education on Nov. 3, 2025.

In Kristen Swanson’s kindergarten class in Chapel Hill-Carrboro City Schools, students spent a lesson studying four pictures of food while discussing the similarities and differences between them, which photo doesn’t belong, and how they came to that conclusion.

Although the exercise doesn’t appear to be mathematical in nature, the students — who were in the first weeks of school — were practicing discussing their reasoning and problem-solving processes in a way that will help them later discuss their mathematical thinking with their teacher and peers.

“The whole process is getting the kids to realize there’s different ways to look at things and share those ideas, and that they all have valid ideas and ways to communicate them,” Swanson said. “You might solve it one way and your partner might solve it another, and you might learn different ways to approach a problem.”

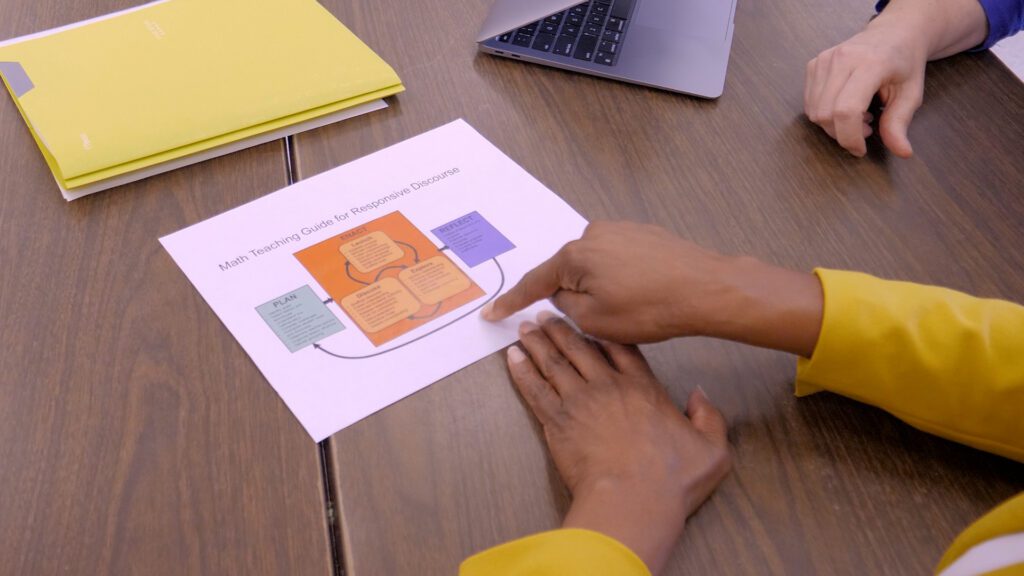

These discussion strategies are part of Project AIM (All Included in Mathematics), a professional development program developed by NC State College of Education Dean Paola Sztajn and Horizon Research, Inc.

Since 2010, Project AIM has used techniques adapted from literacy instruction to help more than 300 elementary school teachers across three North Carolina counties learn to promote mathematics discourse for all learners.

The project expanded in 2022 with funding from the National Science Foundation, strengthening the model by designing support for coaches and principals, and entered into a partnership with Chapel Hill-Carrboro City Schools in 2023 to provide two years of professional development for teachers that concluded at the end of the 2024-25 academic year.

Across several previous implementations of Project AIM, at the end of the professional development, participating teachers demonstrated a better understanding of mathematics discourse, were better prepared to implement high-quality discourse and reported attending to the various dimensions of discourse in their practice. Participants also significantly outperformed teachers who did not participate in the professional development regarding their mathematical knowledge for teaching.

“When I see the progress teachers in Project AIM have made in promoting understanding and math knowledge in their classrooms, I think of the thousands of learners who can be impacted by these great teachers,” Sztajn said. “These students have a larger chance of performing better by third grade, which is a marker that can have lasting effects on their lives.”

![]() Sign up for the EdWeekly, a Friday roundup of the most important education news of the week.

Sign up for the EdWeekly, a Friday roundup of the most important education news of the week.

From math summit to research partnership

In 2022, Sztajn reached out to Noa Stuchiner, director of elementary math and science in Chapel Hill-Carrboro City Schools, to ask about bringing Project AIM to teachers in the district. Stuchiner, who is also a partner in the annual Math Summit at NC State, jumped at the opportunity, particularly after having read “Activating Math Talk: 11 Purposeful Techniques for Your Elementary Students,” a book that stemmed from the work of Project AIM.

“Knowing the story behind the book, I jumped out of my seat thinking about the opportunity our teachers will have by participating in this project to increase their discussion in math classes,” Stuchiner said.

Beginning in the summer of 2023, K-2 teachers in the district began taking 30 hours of Project AIM professional development, which included discussion of strategies outlined in “Activating Math Talk.” The professional development program continued with once-per-month meetings during the school year as teachers implemented strategies in their classrooms and shared experiences with fellow participants.

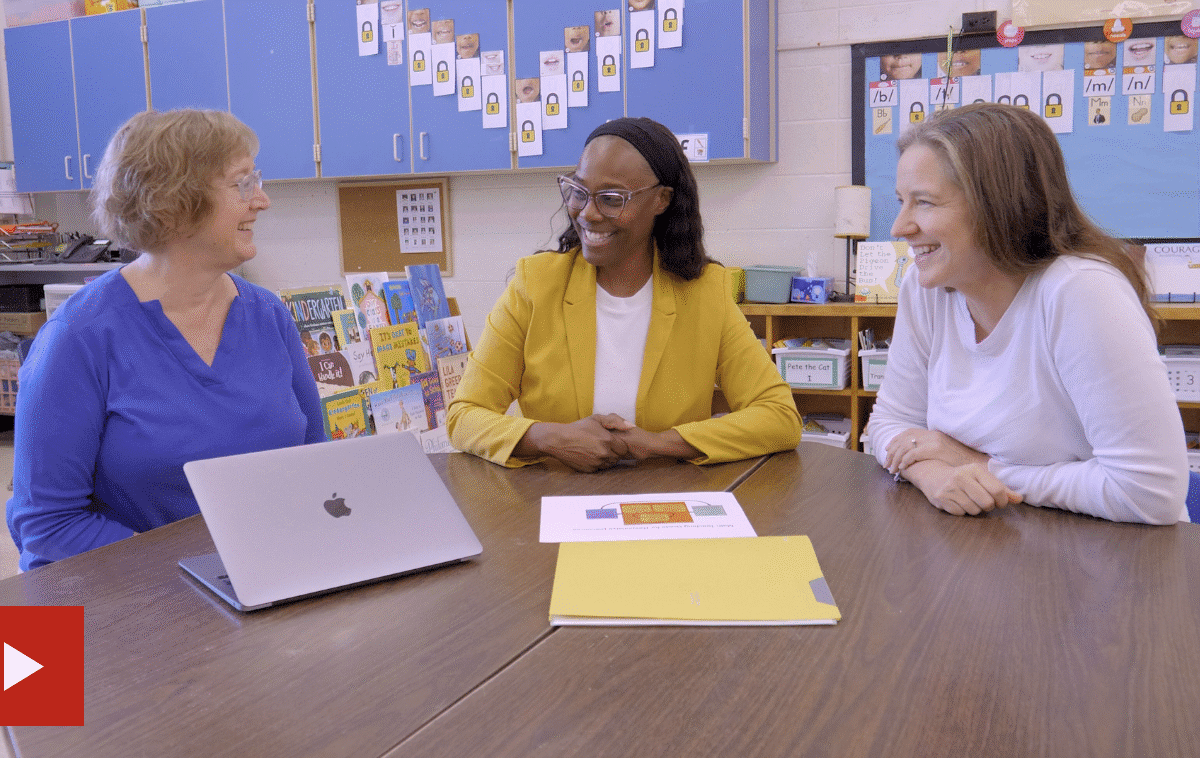

During the second year of the partnership, participants for the first time since Project AIM’s launch engaged in a series of coaching cycles. During each coaching cycle, coach Vangela Eleazer met with all participants from kindergarten through second grade to discuss goals. Then, each teacher, in turn, would work with Eleazer to plan a lesson, implement and film it in their classroom, annotate the video, and share a clip and their reflections with the full team, who would then share thoughts and suggestions.

“To have dedicated time to really sit and dig deeply, share lessons, look at student work together… to share ideas and to analyze our teaching with co-workers was invaluable,” Swanson said. “When we’re doing our planning, we have that common understanding of sharing and thinking about ways to improve math discourse.”

Taking a new approach to mathematics

In her second grade classroom, Christine Cohn has noticed that her students, beyond working to find the correct answers when they solve math problems, are practicing justifying their work and presenting mathematical arguments for their reasoning. Conversations around math now also have a focus on comparing and contrasting multiple approaches to the problems and kids are using multiple methods to support their problem solving and make sense of the math.

Not only are kids showing their work through a combination of equations, number lines, tens frames, and pictures, but they feel excited to share their mathematical thinking with their classmates, Cohn said.

“(Project AIM strategies) really encouraged a lot of higher-level thinking, deeper discussions, and sharing multiple solutions or multiple solution pathways,” she said. “It really opened up a lot of students explaining their thinking and building their thinking together and opening up our minds to different ways to solve problems.”

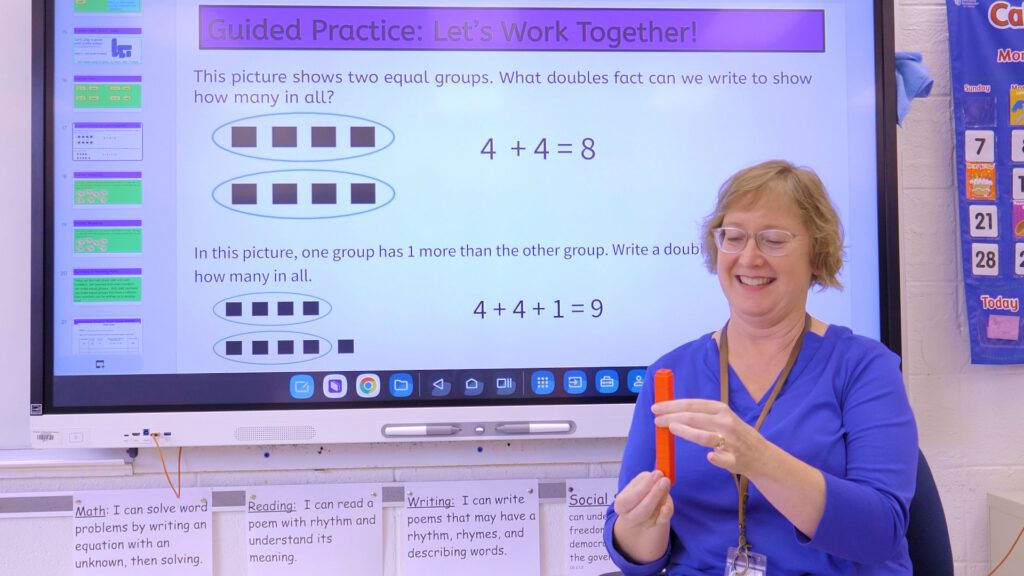

One of the biggest changes teachers said they’ve seen as a result of Project AIM is that they are now guiding lessons that are organized around student thinking. Instead of doing a traditional “I do, we do, you do” approach, lessons now start off by asking students what they already know about a topic and centering them as knowers, as teachers build upon students’ existing knowledge to foster growth in their math knowledge.

The promotion of discussion around math also means that students who may have previously remained silent for fear of sharing the wrong answer out loud are now empowered to share their thought process. These students have more opportunities to share their thinking, which may be correct, or to understand their mistakes and improve their knowledge of math concepts and procedures.

“I’m hearing from all students rather than some, and because we have made a practice of talking about math, everyone knows they have a voice and that their observations are important,” said kindergarten teacher Ellen Royer, who now has a better understanding of every student in her class and where they are in their thinking about math.

For Cohn, the timing of the Project AIM partnership in her district was crucial to realigning her math instruction after several years of teaching online and with social distancing as a result of COVID. With remote learning early on, math instruction relied mostly on teacher-led lectures while the requirement to keep kids six feet apart upon their return to the classroom meant partner- and group-work opportunities were limited.

“It was perfect timing because the Project AIM strategies really helped us to realign our teaching to a lot of student-to-student discussions and whole-class discussions,” she said. “During that COVID time, we were doing a lot of the ‘I do, then we do, then you do’ and that has its place when you’re trying to get information across, but now that we were all back in the classroom again, we really wanted to change how math discussion was happening.”

A lasting impact

As the partnership between Project AIM researchers and Chapel Hill-Carrboro City Schools comes to an end, the impact of the work continues in the district and beyond.

As part of Project AIM, teachers from kindergarten through second grade met regularly to discuss strategies and watch videos of each other’s lessons. Although teachers previously held regular planning sessions with their grade-level teams, the meetings held through work on Project AIM were the first time that teachers from across grade levels were able to plan together.

“One thing we took from that is we really need to plan vertically and take the AIM strategies and talk about what can we do in kindergarten and then what can first grade do after that to build upon it, because we can’t do all of the strategies in kindergarten, but we can start them and then carry on through first and second grade,” Swanson said.

Now, teachers in the school are not only continuing the vertical alignment among K-2 teachers, but want to expand the practice so that third- through fifth-grade teachers are included and the same language and mathematical discourse can extend throughout the elementary school experience.

“AIM is not going anywhere as far as it being a part of our culture,” Eleazer said. “We want to make this an overarching focus for our school.”

Those who have been part of Project AIM in Chapel Hill for the past two years are also helping to bring the strategies to other teachers across the state.

At the 2025 Math Summit, Eleazer and Stuchiner hosted a book study on “Activating Math Talk,” spending an hour-and-a-half session sharing strategies from the book alongside what they’ve learned from participating in Project AIM as well as a video of a teacher from the district sharing her experiences.

“We gave them a copy of the book at the end and the reception was incredible and the feedback we received was that it was so engaging and joyful, but also they went home with ideas and activities to take back to the classroom to use with their students,” Stuchiner said.

For Project AIM, the work continues with partnerships in three new districts in North Carolina, supporting about 150 additional K-2 teachers in the state.

Recommended reading