On a personal level, a week away at the beach played out as it should: grandchildren relishing hours at the intersection of sand and salt water; family gathered for dinners of crab, clam, and mussel; and enough free time to finish three books I should have read years ago.

At the level of public life, however, it was a week that took a horrific turn just after we celebrated the 240th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence. The shooting deaths of two black men during encounters with police, followed by a sniper’s assault on Dallas law enforcement officers, demonstrated yet again how difficult it is for our country to “insure domestic tranquility,’’ an aspiration of the Constitution.

While on vacation and since, I have paid special attention to — and worried about — Baton Rouge, the city where I grew up and where two police officers wrestled Alton Sterling to the ground and shot him. Baton Rouge police say the officers saw him reach for a weapon in his pocket. The incident took place on North Foster Drive at Fairfields Avenue, less than a mile from the house my parents and siblings moved into around the time I graduated from college.

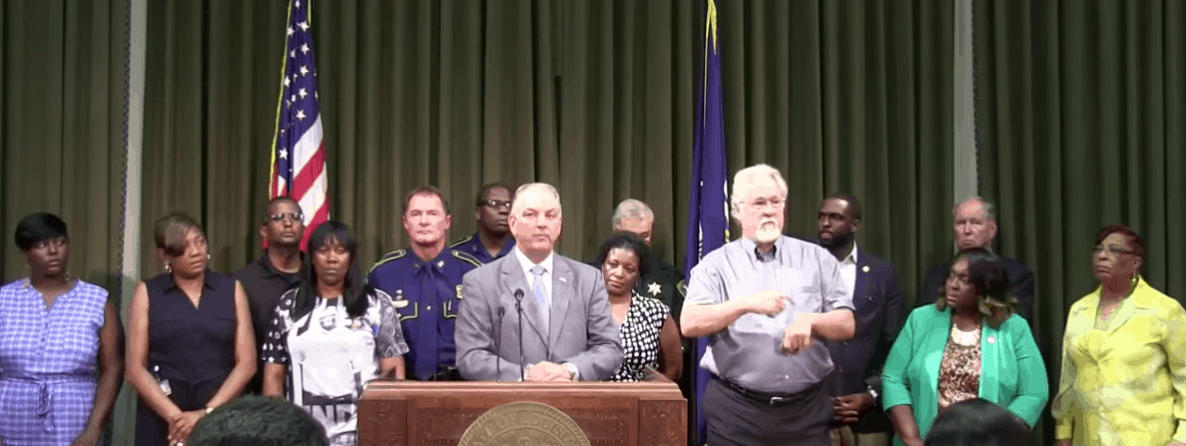

Louisiana Gov. John Bel Edwards moved quickly to arrange an independent inquiry through the FBI and U.S. Justice Department. Edwards, inaugurated only six months ago, is the son and grandson of sheriffs. On the day after the killing of five officers in Dallas, he appeared along with members of the Sterling family, denounced the assault on police, and affirmed the right to peaceful protest.

“This has been a sad week for our state and for our nation,” Edwards said. “We are better than this. We are going to do better in the future…It’s not going to happen if we don’t insist on it and conduct ourselves in a way that makes it happen.”

To do better will require action on multiple fronts, by individuals, civic institutions, and government. Our schools are an indispensable instrument in the long American quest “to form a more perfect union.”

It’s both unfair and unrealistic, to be sure, to dump the whole burden on our public education system. There are police practices to examine, as well as the relationship of police forces with black communities. Churches have a role, as do parents in guiding their children. My old hometown is not alone in having to confront social and economic disparities, illustrated by the clear divide between mostly black and poor North Baton Rouge and white and more affluent South Baton Rouge.

In 2004, marking the 50th anniversary of the Supreme Court decision striking down legalized racial segregation in public schools, my colleagues at MDC, the Durham-based nonprofit research organization, issued a State of the South report that called on the region to reduce racial separateness and strengthen equity in public education – and reminded the South that good schools and strong communities go hand in hand.

That State of the South opened with a quote from a reformist Southern governor of an earlier era — former Mississippi Gov. William F. Winter:

“Discrimination is not limited to race. The line that separates the well-educated from the poorly educated is the harshest fault line of all. This is where we must begin. We must get the message out to every household and every poor household that the only road out of poverty runs by the schoolhouse.”

The schoolhouse is indeed a place where young people get prepared to thrive in the modern economy. But in a democratic society, it is more than that; it is a place for fashioning a more informed and cohesive citizenry.

The school can serve as a welcoming and safe environment in which students with anxieties receive counseling, where they can talk to adults about episodes of violence and about coarse discourse through social media. As educational institutions, the school also must serve as a place to encounter, debate, and learn from the American experience, its tumultuousness, its flaws and frictions, its pattern of hard-won social and economic advances.

As institutions embedded in our society, schools often reflect the society. During the Jim Crow era, schools abetted rather than alleviated racial inequities. Now the trend of resegregation reflects today’s societal fragmentation.

The distressing events since July 4 raise anew the need for federal, state, and local authorities to confront fundamental questions in designing public education policies and budgets:

Will what we’re doing heighten or diminish fragmentation, divisions, and tensions?

Will our plans widen or narrow the fault lines of race, education, and economics?

Do our actions advance our nation, states and localities toward proving that “we are better than this”?