Duplin County is mostly known for its large agricultural economy, one of the largest in the state by most measures.

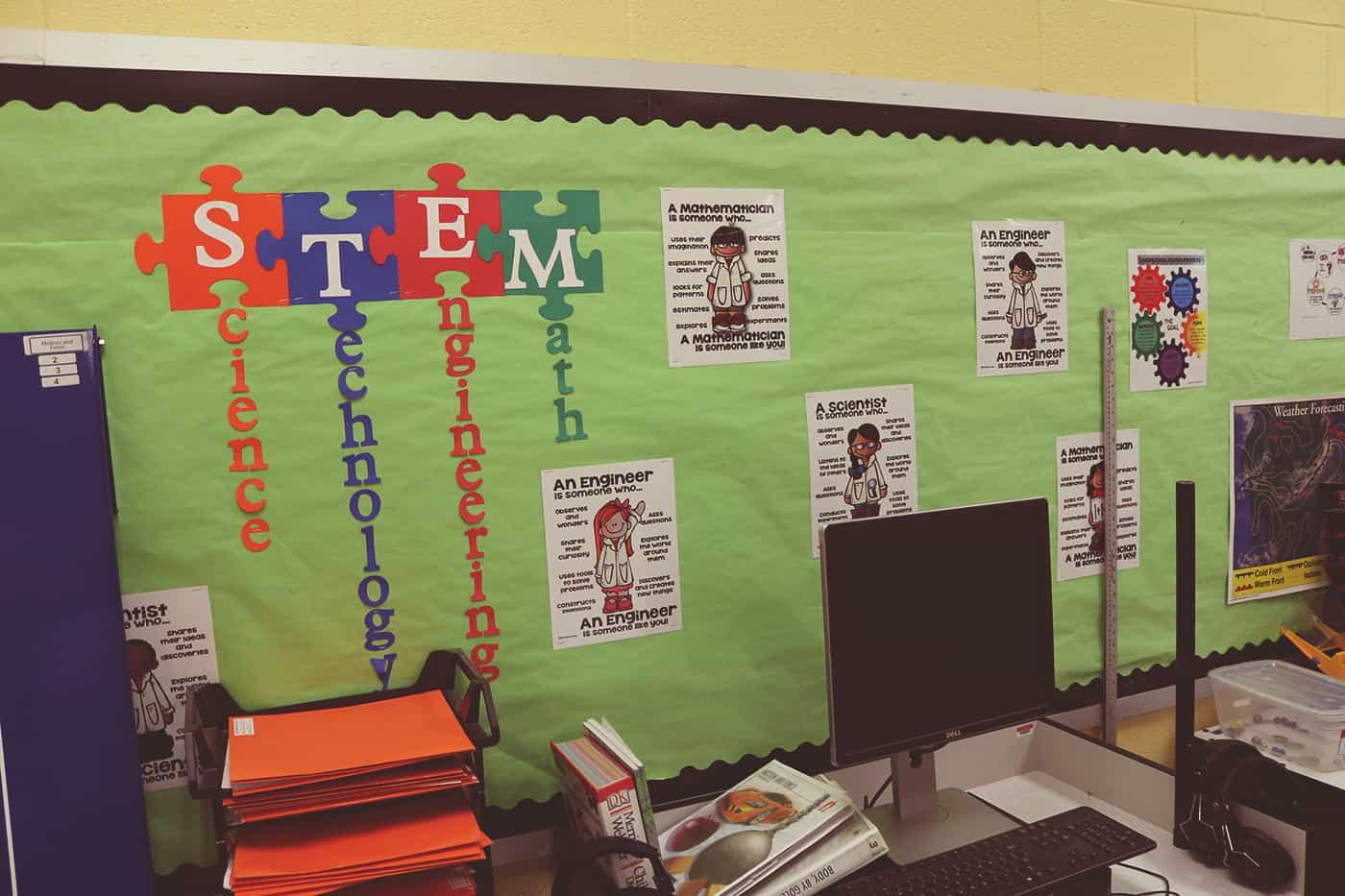

But in this rural county nestled in the southeastern corner of the state, the local school system has launched a STEM-education initiative that is placing high-tech labs in the district’s middle and elementary schools, and creating partnerships between its high schools and local community college.

It all started in 2013 with a grant from the Golden Leaf Foundation to launch STEM academies at middle schools throughout the district. District leaders partnered with education group Pitsco to build the labs.

“We started the STEM implementation project at Charity Middle School,” said Tarla Smith, special advisor for CTE/STEM/Innovative Programs in the Duplin County Schools. “Charity Middle was our first school that came on board. We then modeled what we did there throughout the rest of the system, bringing on the remaining middle schools in the next couple of years.”

According to Smith, with all the district’s middle schools online, leaders began to plan for an expansion of the project into the elementary setting, to expand STEM efforts at the local high schools, and align curriculum with workforce programs at James Sprunt Community College located in Kenansville.

Last year, the first K-5 lab opened at Wallace Elementary School, with plans underway to open labs at three more schools this academic year and four schools during the 2017-18 school year.

Wallace Elementary School is a hive of activity, both inside and out.

Outside the school, construction is underway on an expansion project that will expand the school’s grades from K-5 to K-8.

Inside, there is the typical buzz of any elementary school, children playing in the gym or restlessly lined up in the halls. There is the usual steady stream of activity in and out of the main office.

But the real excitement is outside the doors of the school’s STEM lab. While I was speaking with one of the school’s teacher’s inside the lab, faces pressed against the glass portion of the lab door, eagerly waiting to get their turn inside.

Wallace Elementary Principal Gary Brown would tell me later that the STEM lab was the cause of most the running in the halls at Wallace these days.

“You see the kids’ enjoyment everyday,” Brown said. “They are just excited to get down there.”

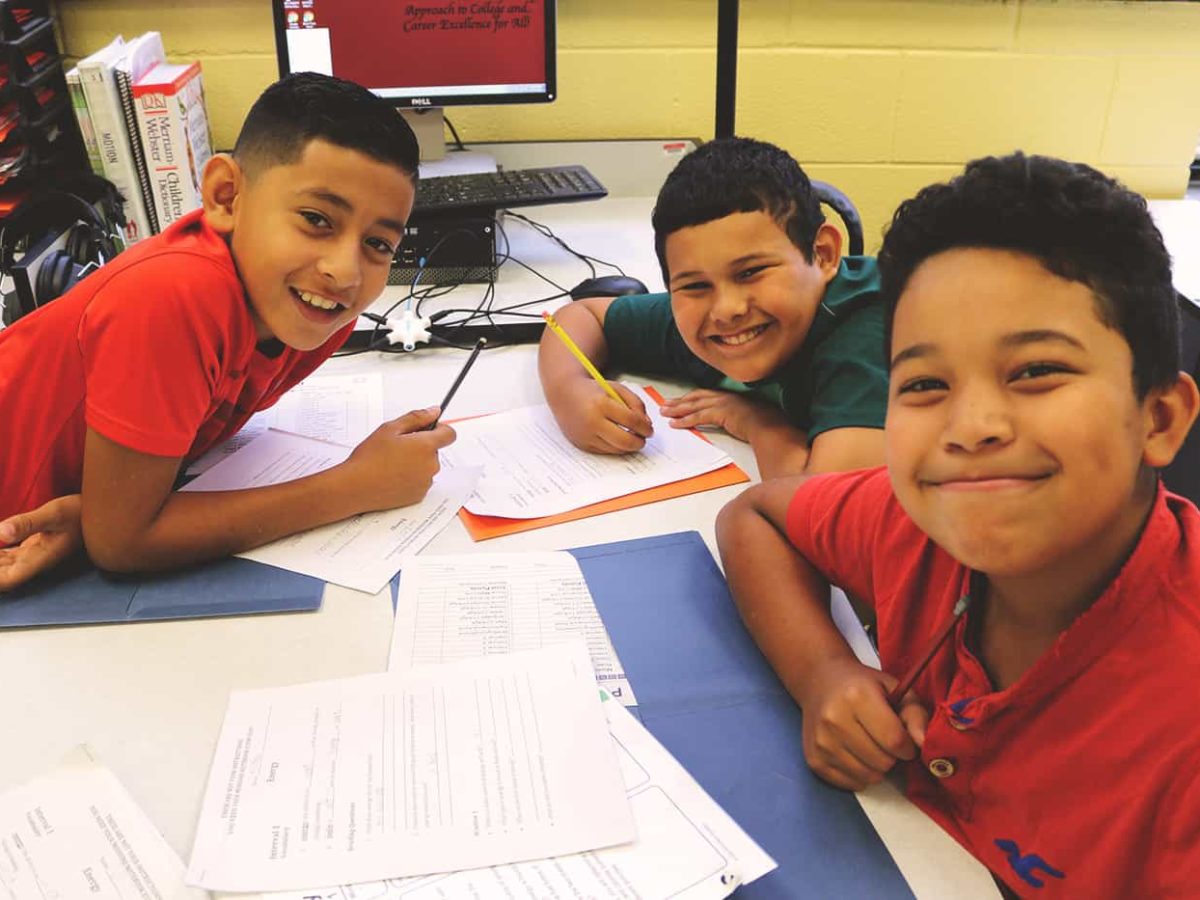

The Wallace Elementary STEM Lab is command central for scientific missions that take place everyday for the school’s third through fifth graders.

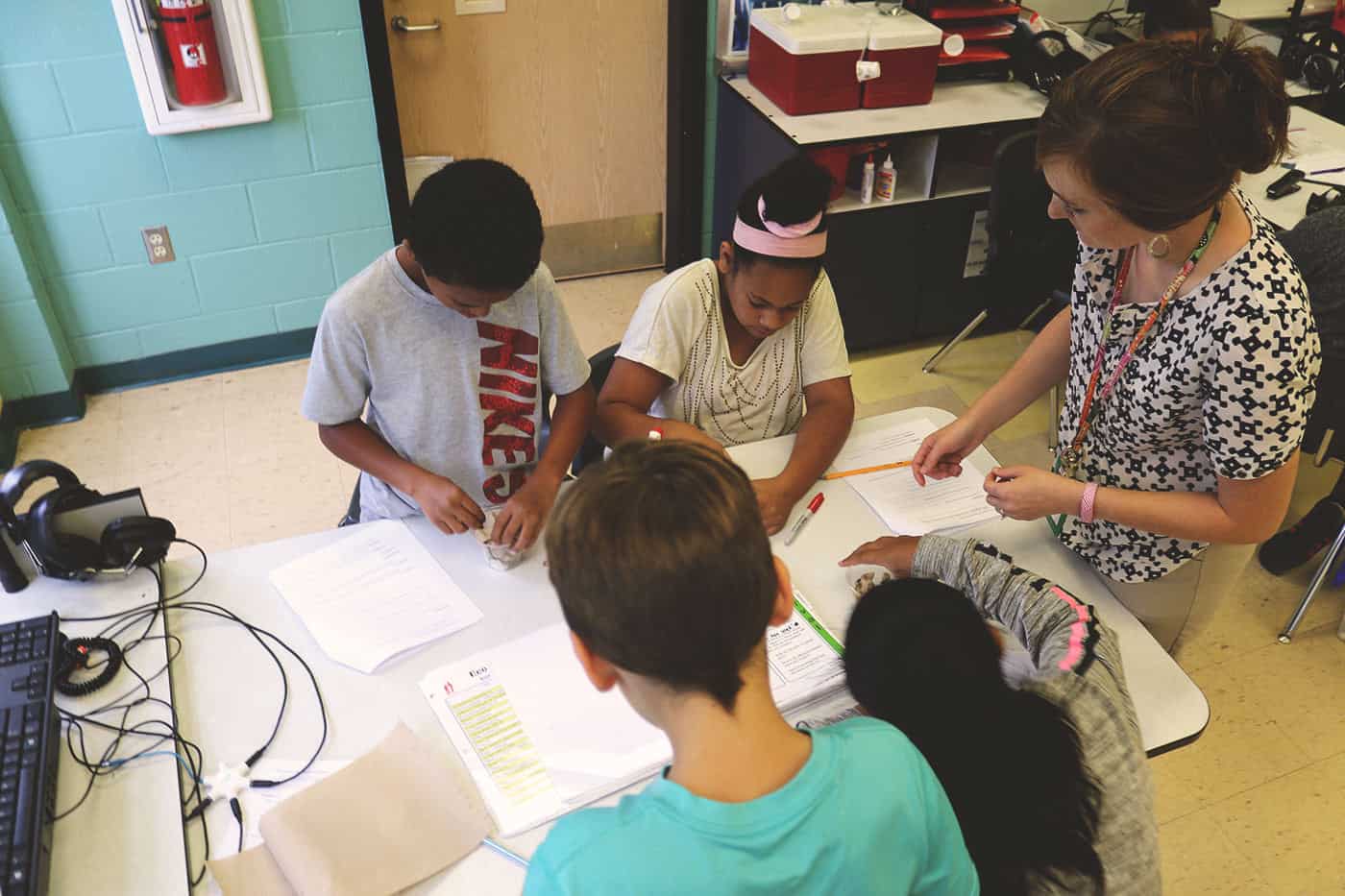

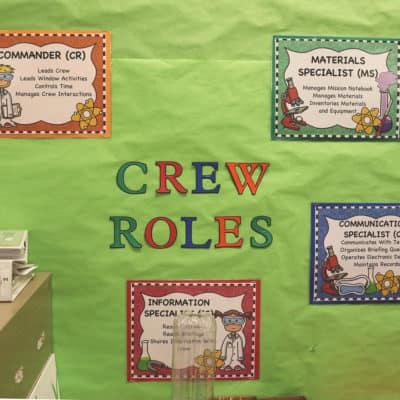

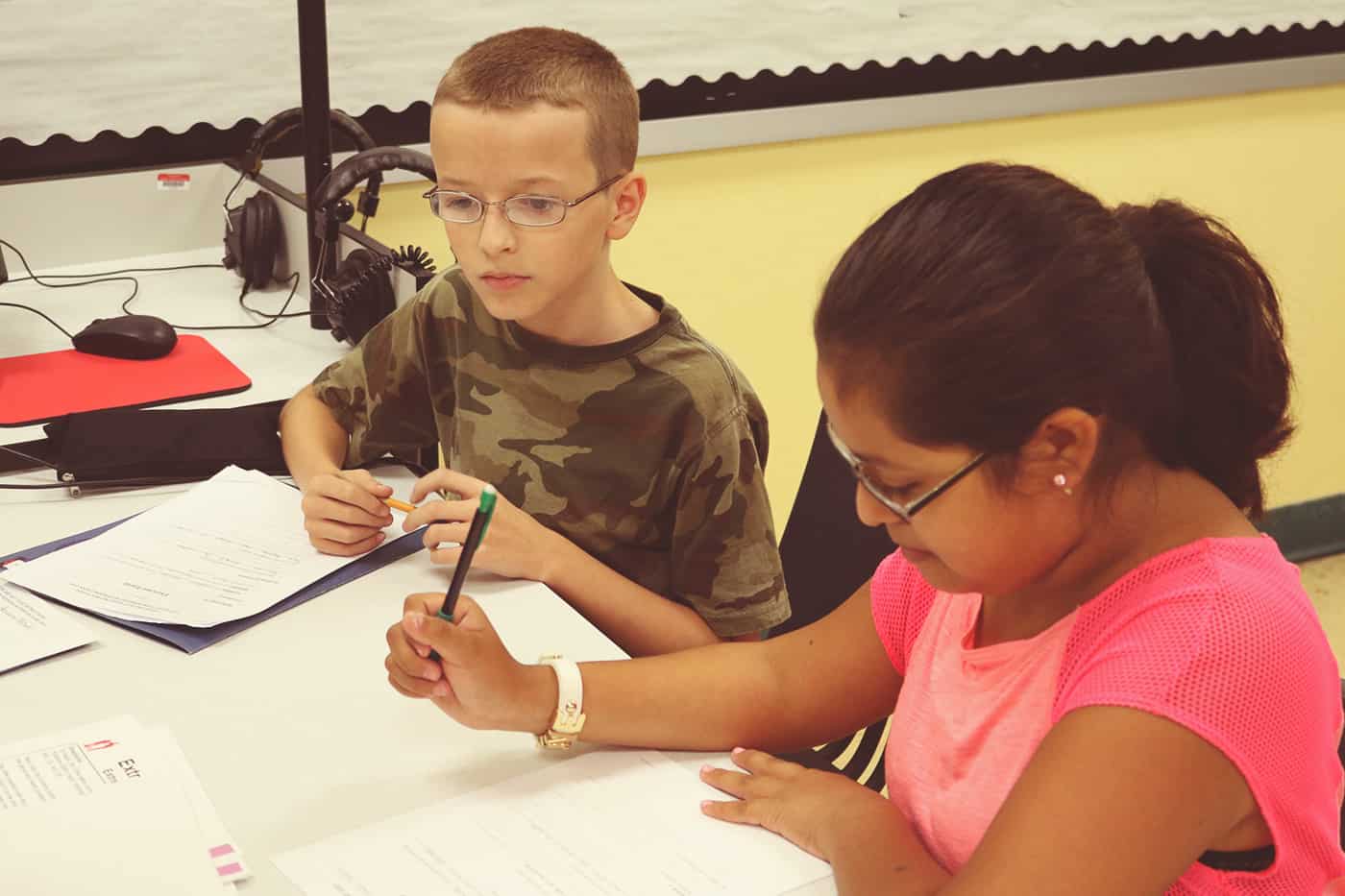

And that is not hyperbole. All of the modules in the Pitsco lab are designed to mimic NASA job titles, with each station — or module — in the lab having a title for each of the four students that rotate through as a crew. There is a commander, a communications specialist, a materials specialist, and an information specialist.

According to Nicole Murray, district STEM coordinator for Duplin County Schools, each school’s STEM lab is divided up into six or seven different missions, depending upon the size of the school.

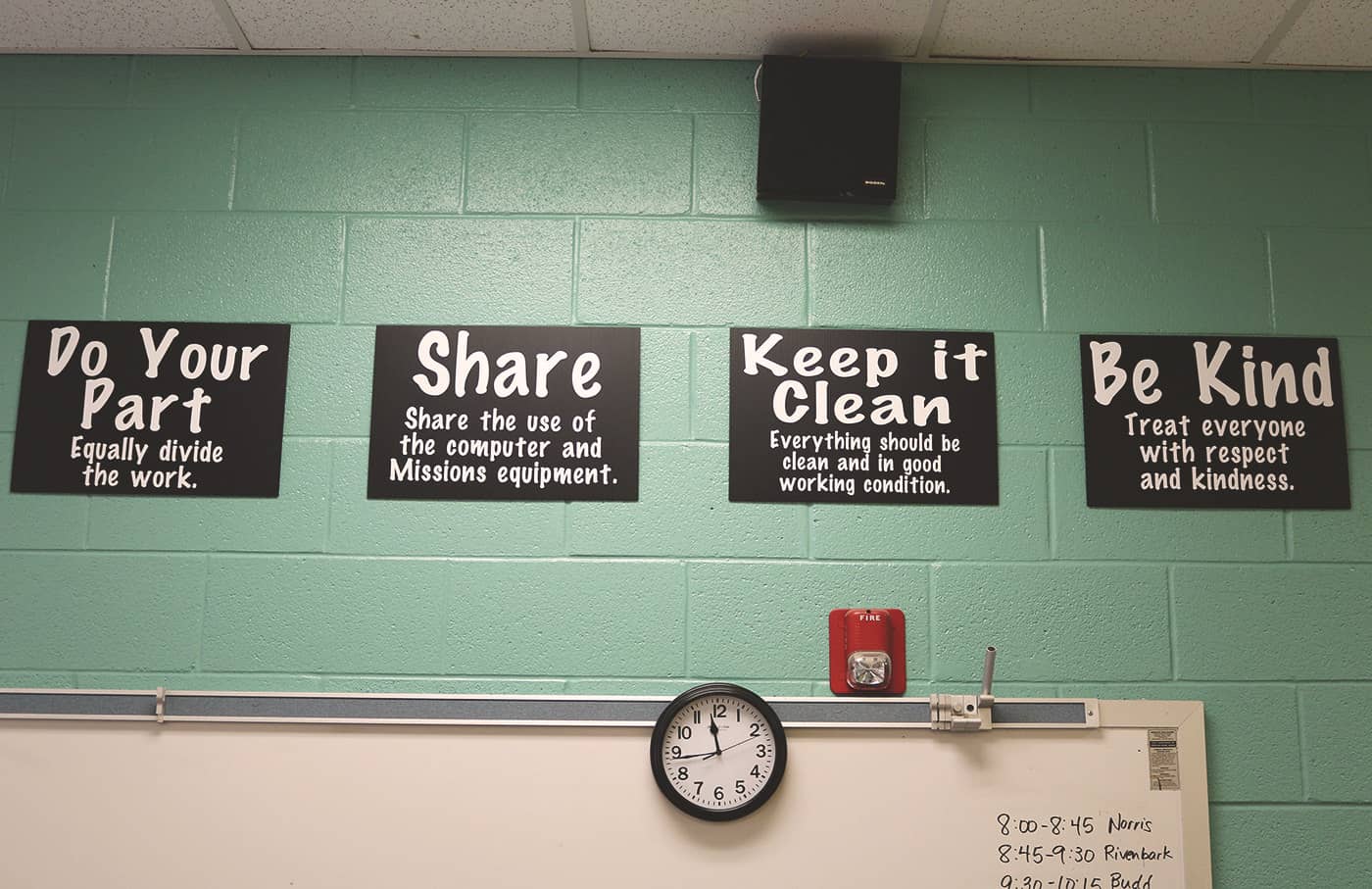

Regardless of the task at at each station, all the jobs carry the same responsibility. For example, the commander directs the crew, assigning tasks based on the assignment in the manuals for each station. The communications specialist is the liaison to the teacher. If there’s a problem or question, and the crew is at an impasse in the project, the students activate a red light to call the teacher. The light is activated at the direction of the commander but only the communications specialist can speak with the teacher. The information specialist is responsible for the project research. The materials specialist gathers the supplies they need to execute the task. They start by taking an inventory of all the group’s materials. That simple step is a way to get kids exposed to unfamiliar science equipment.

“The kids eat that up because you are tying it into a potential career,” Murray said. “And just like in any job, you have a job title and you have job responsibilities. Indirectly, we get to focus on what the world of work looks like, even in third grade: I’ve got to show up; I’ve got to do my job.”

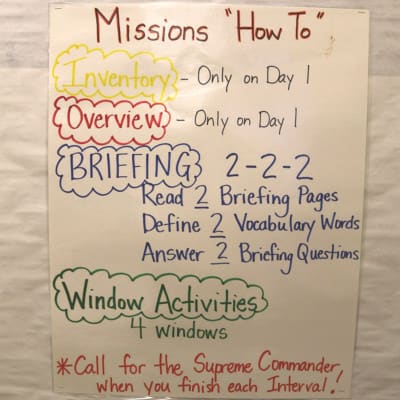

For third graders coming to the lab for the first time, there is a 3-4 day orientation.

“They learn the jobs, they learn the expectations, they learn how to do an inventory,” Murray said. “They learn how to find information they need on the computer. They learn how to appropriately handle materials. They learn how to work within a code of cooperation…All that before they get into any content.”

And like any good NASA mission, each project starts with a team briefing. At the heart of the mission is the project notebook. The notebook adds a literary component to the project. A somewhat undervalued component of any STEM profession.

“Because literacy is such an important component of any STEM field, there is a literacy piece to everything that they do in lab,” Murray said. “We’re working with non-fiction text, which can be difficult for kids, so we are engaging them in nonfiction text by teaching them science that way.”

“We talk [at the orientation] about what makes a good scientist, what makes a good mathematician, what makes a good engineer…at the base of that is being a good reader,” Murray said.

The Duplin STEM and Career and Technical Education team sees literacy as being vital in developing the county’s next-generation workforce, and are dedicated to weaving literacy and writing in to all the district’s STEM labs. That means writing and reading comprehension are at the core of all the lab’s missions.

“In any workplace, whether it is reading and interpreting an instruction manual to operate a piece of machinery, all the way up to being the one who writes the protocols and procedures for the manual, every step along the way, we have to build that foundation for literacy,” Murray said “And we have to build the foundation in scientific, mathematical, engineering and technological literacy, where we are reading technical things, and then we are talking about what we read and we are doing something with it.”

But at the end of the day, the ultimate goal is to instill critical thinking skills.

“The big idea is we are asking them to make meaning of this scientific content, to explain what they have observed in the lab,” Murray said.

The elementary STEM labs mimic the system’s middle school STEM labs with some key differences. The similarities mean when students move into the middle school setting and step foot in their new STEM labs, the transition is seamless and work can begin without a steep learning curve or long orientation. The major difference between the two is that where the elementary labs work in crews of four, the middle school modules require students to work in pairs.

But the ultimate goal is the same. To help students feel comfortable working as teams in a project-based assignment.

“Due to this being project-based learning, it is absolutely interesting to the students; it is something they are thirsty for and thrive in this kind of environment,” said Smith. “Our hope, as a district, is that…we have planted a seed that will continue to allow them to grow.”

Smith and the district have now begun the next phase of the system’s STEM evolution: weaving STEM more seamlessly into the curriculum of the local high schools.

“We have just recently received an additional Golden Leaf grant that will help to increase new opportunities in the high school setting,” said Smith.

According to Smith, the $530,000 grant will help expand training in STEM-related careers that are in demand by local employers.

“The STEM piece in the high school is not as structured as it is in the elementary and middle grades,” Smith said. “What our district’s hope is, is that we bring about more integration in the high-school setting. We can bring about more project-based learning. We already have in place many career and technical education programs that are working to fuel the efforts of STEM. The integration is the key piece. We know that…a single program does not stand alone. You have to integrate the skills in order to prepare the students with the transferable skills they are going to need to be successful in the work place.”

According to Smith, that integration also means curriculum alignment with the local community college.

“We are currently working with the community college to build capacity in the diesel tech academy program. James Sprunt Community College also received Golden Leaf funding to establish and build a facility to provide the diesel tech program because that’s a need in our community,” Smith said. “Prior to this last round of funding from Golden Leaf, we only had automotive programs in three of the four high school settings. When this second round of grant funding and project management is complete, we will have an automotive program in all four high school districts that will feed the diesel tech program at West Park.”

According to Smith, the agreement with James Sprunt Community College will allow high-school students in the diesel tech academy to pursue two postsecondary options when they get to the community college. They can build upon the high school courses they already have and with a few additional courses at the college, leave with a diploma in the diesel tech area. Or they can choose to take the more intensive path and work towards an associate’s degree.

“We are a huge agriculture-based community,” Smith said. “Smithfield Hog Production Division is located in our county, and there’s a huge fleet of diesel trucks on the road every day. They were very instrumental in getting the work off the ground in combination with the community college and with our own school system to build that bridge for the training that will eventually impact the workforce.”

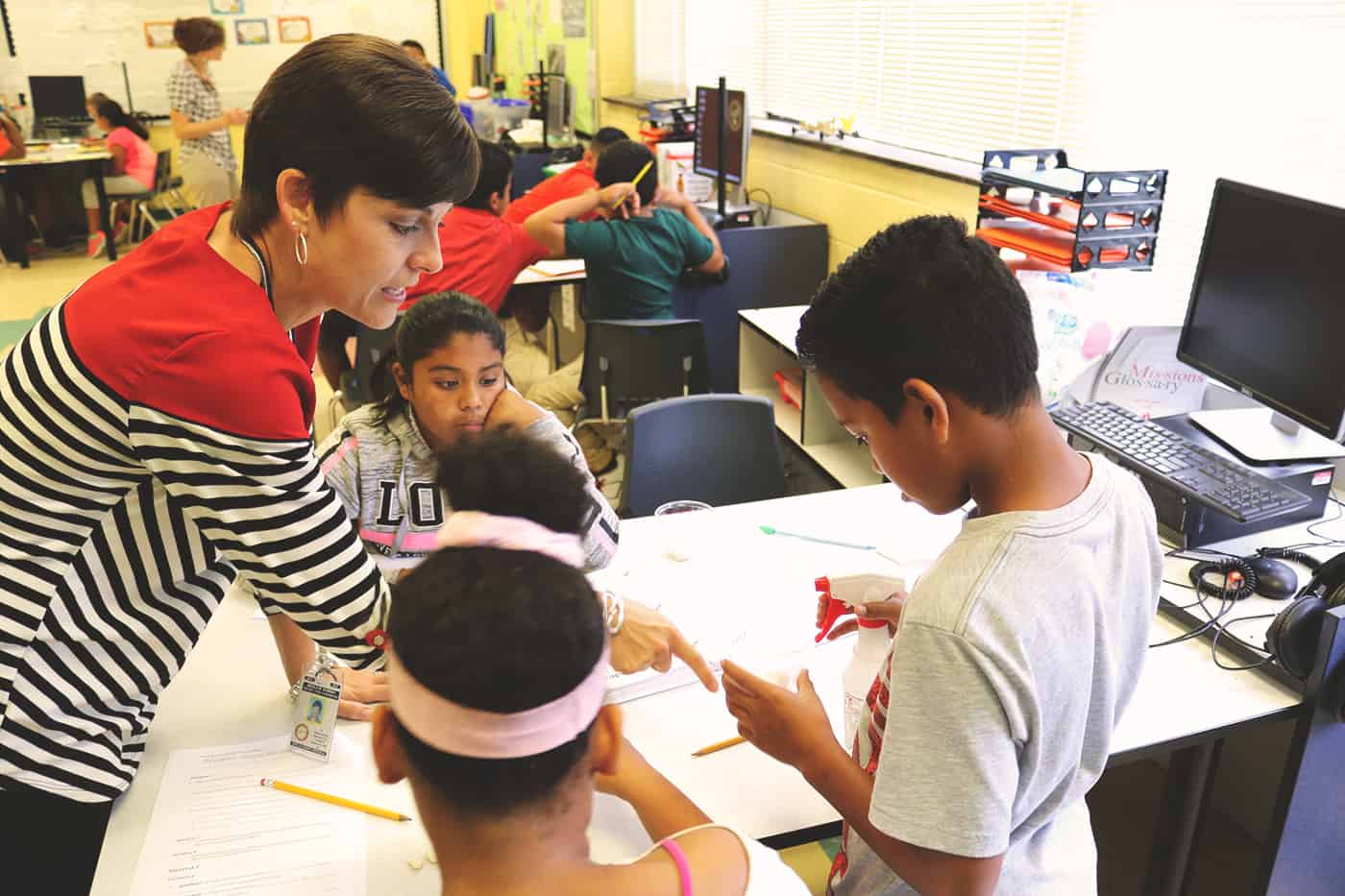

In the STEM lab, teachers step out from behind the desk and, according to Murray, take on the role of a facilitator. The goal is to assist the students in finding their own answers and solving their own problems.

“We are working with them to not fall into [thinking] that the teacher is the one with all the answers, to think that they need the teacher to give them everything,” Murray said. “One of the things you’ll see is that we don’t raise hands in this lab, because if I have my hand in the air, I’m not working. If we need assistance, the kids know what they need to do in a crew to answer a question using all available resources. If they reach a point where the commander thinks, ‘Ok, I can’t take this crew any further, then they will turn the light on on the pole and the teacher sees that, and then the teacher comes over to the table.”

According to Murray, if students do have a question or something they don’t understand the first time they read it, they must still go through a process to gather input and seek a resolution.

“Maybe somebody has got background knowledge that the rest of the crew doesn’t have,” Murray said. “Maybe one is a stronger reader, or maybe one is stronger in math. Whatever the need is, they don’t call for the adult the first thing when they get stuck. We want to move them toward more self-sufficiency and not call on the teacher every time they have a question, because the teacher is not going to always be there.”

According to Smith, that type of teamwork and problem solving are critical skills needed for future employers. “It also supports what business and industry have been asking for for many, many years, and that is teamwork, collaboration and communication,” Smith said. “This type of learning environment fosters that type of learning in a child at an early age.”

And according to Murray, teachers will not answer a question or assist students in problem solving until they are sure the students have resolved every possible avenue for finding the answer on their own.

“Sometimes a teacher will come to a table and the students will ask a question and the teacher will not answer it, because they have not gone through the process of pulling from their resources, whether it be human resources at their table, computer resources, or text resources. The teacher has that discretion to say, ‘Ok, I’m not going to answer that question for you right now. I want you to go through these steps and try.’”

Murray sees that not only as being a way to build self sufficiency, but also as a lesson in the positive benefits of just being flat-out wrong sometimes. Something anyone will face in a job one day. The key is to learn from those mistakes.

“That’s something they have to be taught, and they have to develop a level of comfort and learn that there is no penalty for being wrong the first time,” Murray said. “In any STEM field, in any research or development you are doing, you are going to be wrong many times before you arrive at something right. Developing that comfort in a safe place in not having the answer right the first time, and go back and collect additional data or rethink — that’s one of the things we are working with them on.”

And if you think students in Duplin County have to wait until the third grade to take part in the fun, think again.

“As a part of this grant, in addition to the STEM missions labs for grades three, four, and five, we also have a component for K-2 that is lego based,” Murray said. “We have put lego centers and lego products into kindergarten, first, and second grade. Our goal is for students to learn their science and math, their literacy standards and the skills they need to master. Putting Legos in the classrooms gives the teachers and the students another tool to learn material and to demonstrate mastery.”

But, by having that type of product and curriculum in place, you begin to put students in groups, and in those groups students have jobs that they have to do.

According to Murray, having that curriculum in place at the start of a student’s academic journey means exposing them to project-based learning and teamwork early so those skills are embedded not only in time for the STEM lab, but also present in all their academic experiences.

“So not only are they learning their content skills, but they are also learning the skills of cooperation, written expression, and verbal expression; how to resolve a disagreement,” Murray said. “And we knew that it is important to start those skills and aptitudes as early as kindergarten.”

Murray says the STEM concepts are also incorporated in the district’s K-5 physical education classes.

“We have purchased equipment so they are doing the ‘STEM in the Gym’ program. So several times a year students work with simple machines like large, oversized gears, pulleys and inclined planes,” Murray said. “The kids are engaged in physical activity but they are having to figure out how these simple machines work in the context of exercise and physical fitness.”

“This is my third year using the lab. It has been really awesome,” said Elizabeth Budd, science and reading teacher at Wallace Elementary. “It’s hard to put into words the difference in the learning the students are doing here in the lab as opposed to with a traditional sit-down science lesson. The use of manipulatives and the way they can do hands-on learning really changes the playing field for a lot of students.”

Budd has seen how the un-traditional classroom setting of the STEM lab has helped some of her students discover their own special talents, and reinforced an understanding that intelligence can take many different forms.

“Last year, I had a student, and he started off the year and was crying all day long,” Budd said. “He felt like he was unsuccessful in school. He was not confident at all. It was a real battle in getting him to do work and feeling confident in that. He was the kind of kid who loved Legos. He came into the lab and I put him at the station that involved [demonstrating] motion and force with Legos, and he just blossomed. It was hilarious cause he was like, ‘I know how to do Legos. Let me show you all,’ and he kind of took a leadership role, which was not expected at all. Then that built his confidence.”

According to Budd, the student was able to carry that boost in confidence throughout the rest of the school year.

“I saw a huge change for him throughout the whole year,” Budd said. “And it was just because of the lab. He was using the materials and felt confident, just from that station, and he carried over to the next one. His parents called me and were like, ‘Whatever you are doing, it’s working. We’ve never seen this side of him before.’ It was really amazing.”

Teacher Rebecca Norris, who was visiting the lab with her fifth-grade class, had seen a difference in her students as well.

“It gives them the chance to take more responsibility of their own learning, and not focusing all on me all day,” Norris said.

“When they feel like they have figured it out on their own, it just boosts their confidence,” Norris said.

“It’s phenomenal,” said Principal Brown, about the effect of the STEM lab on his students. “I’ve had the luxury of seeing it operate in the middle schools. And now seeing it in the elementary school, it really addresses those science standards.”

“I really enjoy getting in that STEM lab, especially at this level,” Brown said. “You see those kids and their eyes are lighting up, because they can use their hands…you go in there and they have their fingernails dirty. They’re playing with earthworms. And all those kids really enjoy it.”

“Science touches so many aspects of life,” Brown said. “We talk about critical thinking, problem solving, all that’s embedded in science, and you see it at work everyday.”

Brown thinks the team concept being instilled in the students is essential to building critical thinking skills and learning the important lessons of responsibility and dependability, all of which are skills employers are seeking in the workplace.

“One thing about the STEM lab is it forces them to work in teams,” Brown said. “And it’s really a team, it’s not just a group of four kids or five kids. The teachers teach them that interdependence amongst one another. And the team won’t function if one of those kids is not on task, doing what they are supposed to be doing. There’s a lot of accountability to each other.”

But what fascinates Brown the most, and causes him to shake his head in disbelief, is the fascination with STEM and STEM careers that he hears from his students everyday.

“In all my years in education, I have never heard so many kids talk about science-related professions,” Brown said. “I had a kid the other day tell me they wanted to be a botanist. And I asked them, ‘What is a botanist?’ and they could tell me!”

“Some of the careers they come up with, I have to go back to my office and double check and make sure they were telling the truth,” Brown admits with a laugh.