This is the fifth and final piece in a week-long series on schools, districts, and organizations across the state using data in innovative ways. Read the first piece on Shamrock Gardens Elementary School here, read the second piece on UNCC’s Institute for Social Capital here, read the third piece on South Rowan High School here, and read the fourth piece on Rutherford County Schools here.

At Grand Oak Elementary School in Huntersville, students are the creators of knowledge. They move through course material at their own pace, aware of their strengths and weaknesses and leaning on their fellow classmates for support. This use of personalized learning (PL) is made possible by the school’s focus on data — both academic and social-emotional — which allows teachers to meet students where they are.

Raymond Giovanelli, principal of Grand Oak, sees data as a tool to reach the school’s overarching goal of best meeting students’ needs. Whether it is driving instruction in the classroom or determining when and how students take movement breaks throughout the day, data serves to better inform the school’s practice and helps to gauge what the school should and should not continue to do.

Now, let’s take a look at how data drives both the personalized learning model and kinesthetic learning experiences at Grand Oak Elementary.

In 2014, Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools received a grant from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation to explore personalized learning. Grand Oak Elementary joined the inaugural cohort of 15 schools and began implementing PL in the 2014-15 school year. Additional schools were added to the initiative each year, and personalized learning is now emphasized district-wide.

Pre-assessments are used at the beginning of every unit to determine a student’s mastery of a particular set of standards. During professional learning community (PLC) meetings, teachers boil down each of the state’s standards into goals and then develop pre-assessment questions that reflect each of those goals. Teachers also determine what counts as mastery for each goal. For example, mastery might be getting both questions related to that goal correct, or it might be getting at least three out of the four questions related to that goal correct.

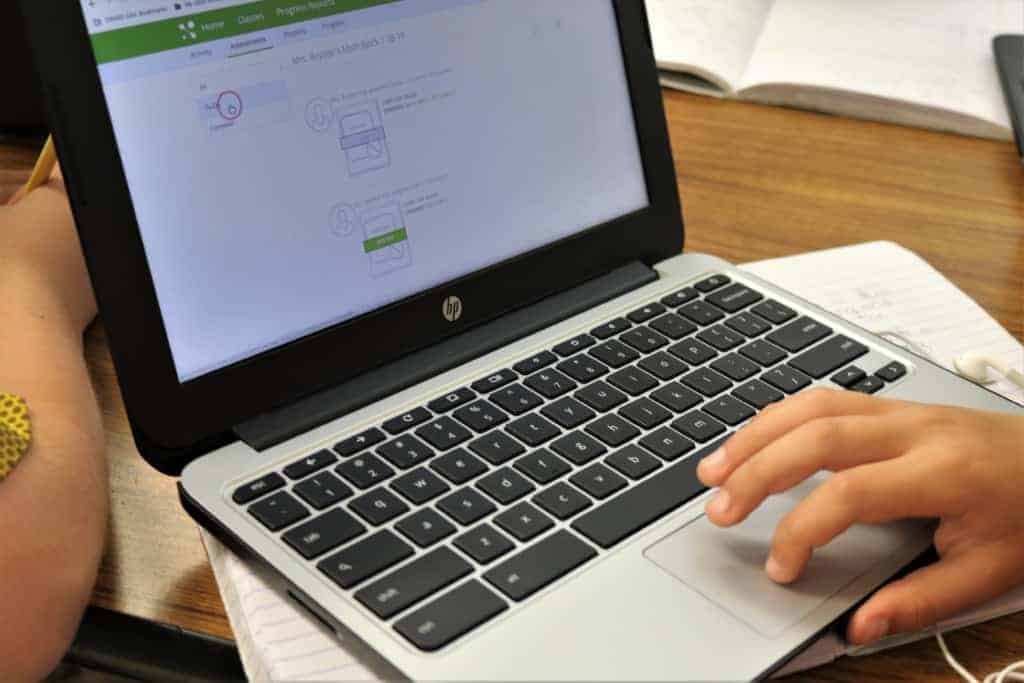

These pre-assessments take on various forms — they could be quick online activities, a few open-ended questions, or a more observational assessment, such as watching a group of students as they discuss a set of vocabulary cards to identify geometrical shapes.

Grand Oak Elementary

– District: Charlotte-Mecklenburg

– Location: Huntersville

– Enrollment: 562 students

– Performance: Exceeded growth from 2014-16, met growth in 2017 and 2018

– 12.1% of students are economically disadvantaged

The goal of these pre-assessments is to test a progression of skills and offer students multiple ways to show mastery.

“If I’m a fifth grader and I’m expected to do multi-digit multiplication, and I don’t have basic multiplication, or the problem solving strategies to access larger digit multiplication, I need to start there,” said Jennifer Sieracki, a math and science facilitator at the school. “So we kind of backtrack and give kids opportunities to see maybe where the breakdown might be.”

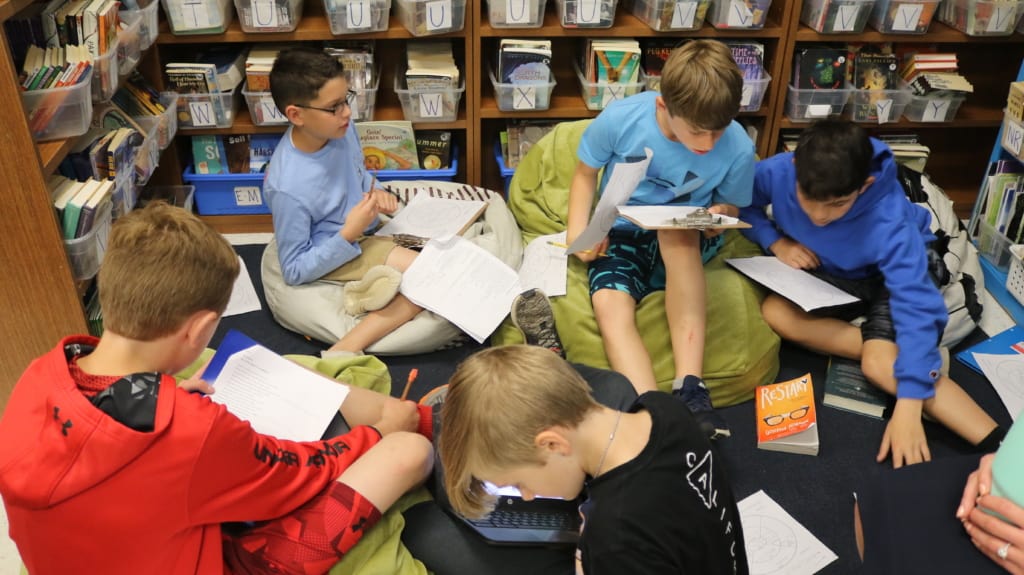

Then, using data from pre-assessments, teachers create mastery groups — like mastery, partial mastery, and no mastery — to focus on what each student needs to fill in the gaps in their understanding of the standards. A typical day might start with a pre-assessment followed by a whole-group mini lesson. Then, students may move into small groups with teachers to hone specific skill sets.

That small group time is incorporated into traditional class periods and also offered during a 40-minute extension support period tied to the end of the reading and math blocks in third through fifth grade. Originally, the extension period was only once a day for both subjects — but that schedule meant that students who needed extra support in both reading and math were only able to receive extension in one of those subjects.

After pre-assessments are complete and small groups are formed, some teachers offer mastery sheets for each of the standards in the form of a “playlist,” where the standards are listed in order with the student’s weakest standard at the top. Students move through their playlist and complete their mastery sheets at their own pace, which often involves accumulating multiple pieces of evidence to indicate mastery.

In this phase of the PL process, learning is student-driven — they can select from a range of tasks to display mastery for each goal. Once students complete a mastery sheet, they might engage in a peer review with a fellow classmate or conference with a teacher to check in on their progress. After completing that conference, they complete a checkpoint or exit ticket to determine mastery before moving on to the next standard.

According to a host of teachers at Grand Oak, this PL process gives students a sense of ownership over their learning, instills confidence, and fosters curiosity.

Chrystal Cavanagh, a third grade teacher at the school, sees this especially among her students as they move through a year filled with transition where they are expected to be more independent.

“Because it’s not a teacher walking them through everything, they do so much on their own that they build that independence, and then they build confidence too,” said Cavanagh. “That’s what I love to see — I love to see those kids who come in and say: ‘I hate math, I’m not good at math.’ And then they just build confidence with it.”

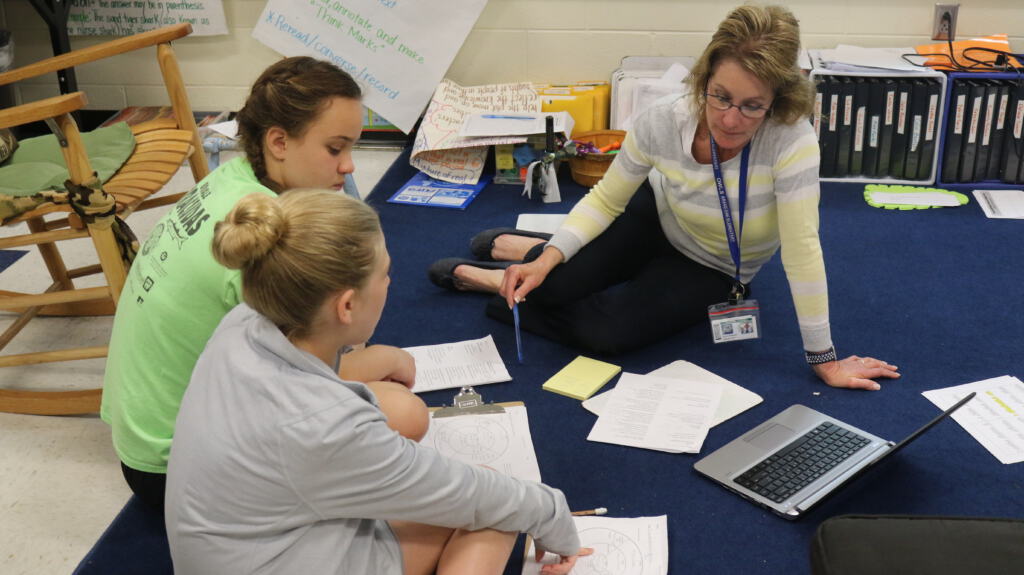

PL also gives students at Grand Oak the chance to pull their own experiences and passions into the classroom, creating and sharing knowledge with one another as they move through each standard. Jennifer Kershaw, a fourth grade teacher, is quick to admit when she doesn’t know the answer to a student’s question, and then she encourages the student to work with her to figure it out.

“Kids really look at teachers [like] we’re not givers of knowledge anymore. We guide them to get the knowledge on their own. And they realize that we’re all learning along the way as we go,” said Kershaw.

This hits on something that Sieracki believes is key to a successful personalized learning experience: open mindsets.

“Unless the teacher is willing to share any control in their classroom and not be the power, then you’re not going to get anywhere. You have to be willing to share your data with your kids,” said Sieracki. “That open mindedness is really integral.”

Grand Oak also emphasizes a range of “soft skills” used to build social-emotional learning in their students. Recently, the school added a second guidance counselor, giving the school more capacity for classroom lessons on various interpersonal skills. Giovanelli hopes to create brief surveys that would assess the impact of these lessons on students.

“If we’re going to teach kids about bullying and how to handle it, we need to have some sort of a survey or processes to see if we’re making an improvement in how students handle bullying,” said Giovanelli. “Are they feeling safe? Or are they more comfortable in how to handle those situations?”

Another key to Grand Oak’s implementation of PL, according to Sieracki and a host of other teachers, is flexibility. PL may look different depending on the teacher’s comfort level with the process or the needs of their students. While some class periods may use a lot of small group instruction, others might have their students rotating through centers or working completely independently.

“Even with my two blocks, the process looks totally different,” said Cavanagh. “With one group of kids, it’s still a lot more like structured and we walk through pieces step by step. Whereas in another group, I might have 22 kids and 22 different places, because they’re a little bit more independent.”

Teachers at Grand Oak have the ability to iterate their PL model to better suit their students needs and have the support from their administration to acknowledge when things aren’t working.

“We spend a lot of time school-wide talking about growth mindset,” said Sieracki. “And so we’re establishing a culture where it’s OK to try and fail, and that’s really important to kids feeling comfortable taking risks and the teacher being OK with that.”

It’s a Tuesday morning in late April, and students at Grand Oak Elementary are rotating between stations in the media center where they practice walking on their hands and feet, balancing on short beams, and jumping rope. This is a typical sight at the school, where kinesthetic learning is now blended into every classroom.

The school’s focus on movement was first inspired by Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools’ B3: brains, body, behavior program. The purpose of that program is to help students develop motor skills that “spark their brain, build their bodies, and improve their behavior to increase academic performance.” And the research backs this concept up — one study suggests that students be given “frequent physical activity breaks that are developmentally appropriate.”

With the B3 program and research in mind, the school set out to integrate movement into its classrooms. During the 2017-18 school year, Grand Oak created the first cohort of “Active Owls,” a group of 16 third grade students that scored a level 1 on their Beginning-of-Grade 3 English language arts/reading assessment, a few of whom also had behavioral issues in the classroom.

For 30 minutes before school, those students worked with their physical education teacher to engage in kinesthetic movement and activity. Over the course of the year, the school tracked the students’ data, including their Measures of Academic Progress (MAP) assessments, behavioral outcomes, and school report cards.

The results were encouraging. According to Giovanelli, the majority of students in the cohort passed the third grade End-of-Grade exam, and there were also improvements in school report cards and MAP assessments.

“It allowed us to have multiple data points to kind of say, did this benefit this group of students? And it went so far as the other grade levels started to ask for it to be integrated during the day,” said Giovanelli.

For Giovanelli and his team, data provides a tool to help gauge what they should and shouldn’t continue to do. In this case, the data was promising, and movement is now offered to every student at the classroom level.

When movement breaks were first implemented school-wide, music would play over the speaker system every 30 minutes to give students a movement break on a set schedule. Based on survey feedback from students that said that pace was too frequent, the school decided to scale back to offering breaks every hour. Now, movement breaks are more naturally embedded into daily classroom routines — the result of an iterative process based on student survey data.

Students take “brain breaks” as they need them, completing a few jumping jacks or lunges, or stepping in the hall to jump rope. And teachers more naturally incorporate movement into lesson plans, such as hanging math problems around the room that students rotate through.

These practices, according to teachers at Grand Oak, have allowed students to become more self-aware of when they need to take a break and refocus.

“I think that reset piece is important too. Like, we just had a really challenging time with something, let’s do something really silly and goofy for a minute, because we just spent 30 minutes trying to tackle equivalent fractions,” said Cavanagh. “Now we take a break and just forget about fractions, and it kind of gives you that moment to be goofy.”

Editor’s note: The Gates Foundation supports the work of EducationNC.

Recommended reading