Forest Hills High School

“Talent matters,”

says Kevin Plue, the principal of Forest Hills High School, to Ann Goodnight, the director of community relations at SAS and education philanthropist.

Plue says education improves dramatically with the “hiring, training, and retaining of high-quality teachers.” He also needs his teachers to be passionate. With four teachers involved in the Partners in Learning Collaborative, Plue says, “it is evident this program is doing that.”

Plue says a high-quality education comes down to three things: the leadership of the school, the quality of the teaching, and parent involvement. “We can control two,” he says.

“Teaching is a really hard profession,” says Plue. When it comes to retaining high-quality teachers, he says two things make a difference: a master’s degree and national board certification. Those teachers are more likely to stick with it, he says. “They don’t leave. They are invested.”

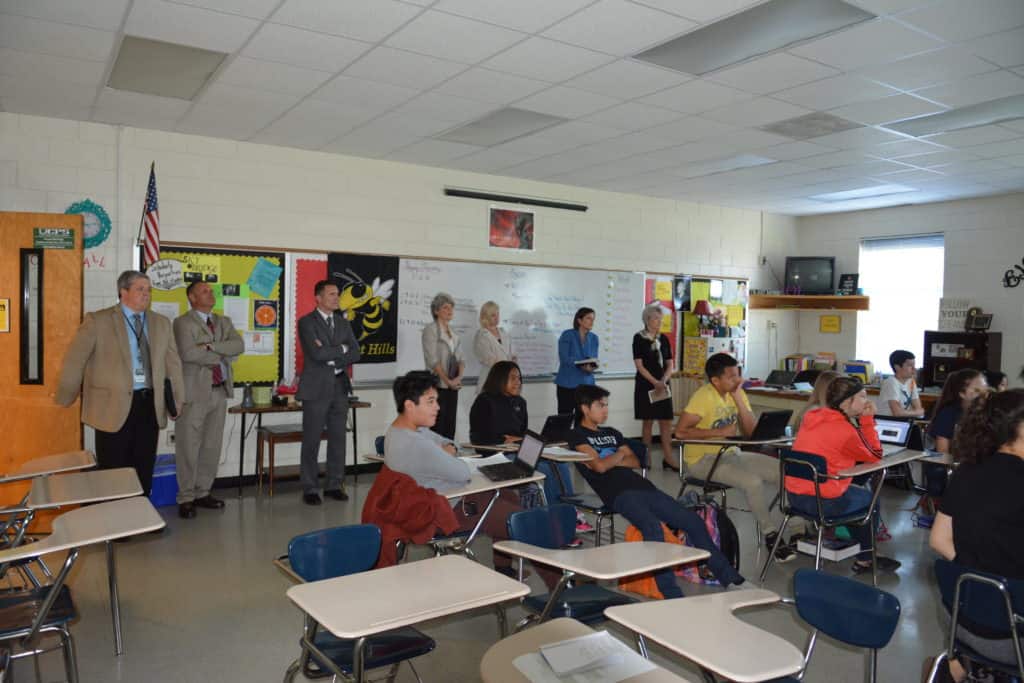

Just how invested they are was apparent as soon as our entourage of leaders from the Goodnight Educational Foundation, UNC Charlotte, and the Union County Public Schools entered Christina Rose’s classroom. Rose was teaching Kate Chopin’s short story, “The Story of the Last Hour” to her 9th grade Honors English class. First published in Vogue in 1894, the story is about “the thoughts of a woman after she is told that her husband has died in an accident,” according to the Kate Chopin International Society.

Goodnight noted, “The students were definitely engaged. They didn’t even know we were here.”

We are kids.

We like to laugh.

We want to learn.

Rose says the Partners in Learning Collaborative helped her move from a teacher-centered model — I stand and I lecture — to a student-centered model. When she plans her lessons, now she puts herself in the shoes of the students, thinking about where the students fit in our society. Caroline McCullen, director of education initiatives with SAS says, “That explains the level of engagement.”

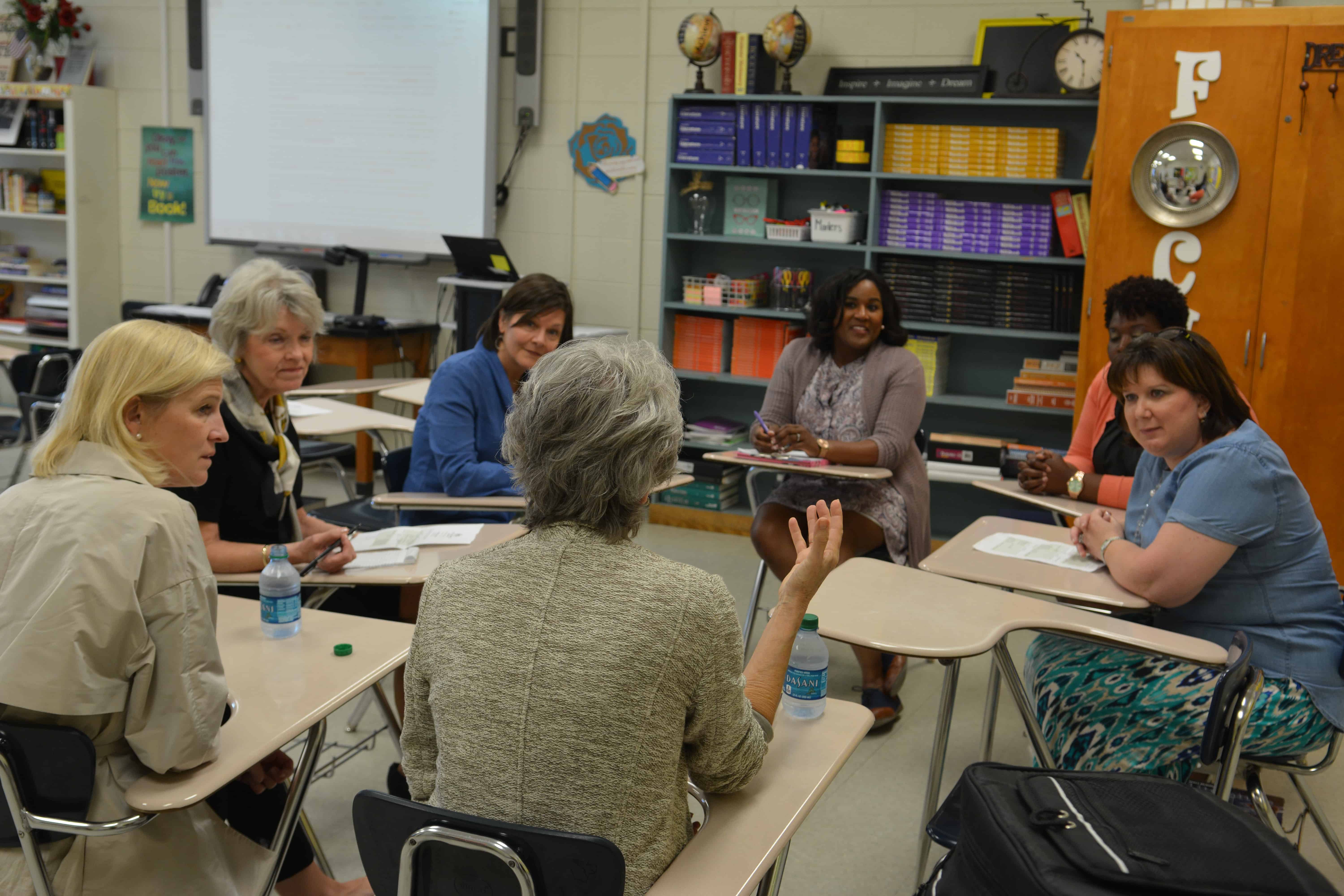

After class, Dean Ellen McIntyre led a focus group with the teachers, asking them:

Rose says, “I’ve learned to give the students more time to dig into the text. Looking at how the brain actually operates, I now give them time to process the information and think.”

She has also learned “how to group students appropriately in the classroom,” understanding that her small groups should model what the school looks like. She says how students are arranged can lead to significant growth. Rose says, “Students are concerned with the other students. The focus is on the group. They want to grow.”

Mechele Tucker has been teaching 17 years. She says of Partners in Learning, “This is from heaven.” The collaborative made a master’s degree financially attainable, but more importantly it provided her with the “unbelievable experience” of working collectively with a group of teachers, “bouncing ideas off each other, trying different things.”

Tucker says the program “benefited more than just me,” helping her PLC (professional learning community), which was teaching the same ideas and using the same process. Plue raises this as an example of the organic, grassroots leadership of teachers that took hold over the course of the year. He says, “Teachers see Mrs. Tucker in the trenches with them.” At this high school, PLC’s are the primary school improvement strategy. For Tucker, Partners in Learning “has been life changing personally and professionally.”

When it comes to teaching, Tucker says she learned that “critical thinking is the start, but critical literacy is the goal.” She revamped her entire King Lear lesson after taking a class in critical literacy. She built the lesson around the family dynamic involved in the play, knowing the students could connect by asking the question, “What kind of parent do you want to be?” Tucker says, “It took the play to a whole different level for the students.”

Shfante McGee says, “Every child can learn.” Her classes are now intentionally designed “to reach all of the kids.” She says, “We want to grow. We want our students to do better. We want to be better professionals. This program helped us do that.”

Christy Humphreys said the embedded coaching in Partners in Learning allowed her professors to see her students and see how she teaches. Humphreys says of her professor, “She saw us. She watched us. She connected pedagogy to content.” But even more importantly, “She came all the way out here to see us. That doesn’t happen in a traditional master’s program.”

Here is Humphreys talking about the need for literacy in math classes:

Plue says Forest Hills High School is 39 percent white, 34 percent black, 24 percent Hispanic, and 3 percent other. Seventy percent of the students are eligible for free or reduced price lunch.

He says, “Almost all of the ESL (English as a Second Language) students speak Spanish. It’s monocultural.” He says when students have a similar culture and language, the camaraderie of a shared culture means students tend to socialize in their native language and there is not as much of an incentive to learn English. This group of teachers wanted to know what they could do to help.

Partners in Learning arranged a field trip for them to South Mecklenburg High School in Charlotte. Field trips were added to the program to allow teachers to see best practices and bring them back to their schools. On this field trip, the teachers said they learned “they must embrace the different cultures in their classrooms.”

There are cultural barriers. We must talk about them.

South Meck has a Spanish PTA. It was an a-ha moment for these teachers. Goodnight says, “That gives me goosebumps.”

These teachers are learning about how Hispanic parents think about the American education system, the expectations they have for their children, and how these parents think about the role of the teacher. They are learning about the resources that exist in their community for these students. They are better able to create plans for academic success at school and home. Their lessons are tailored to reach more students.

Tucker says, “I didn’t know how easy it was for us to help.”

Monroe High School

Dr. Michael Harvey is the principal of Monroe High Schools. “Partners in Learning raised the level of engagement in the classroom,” he says. “This wasn’t meant to be a secret club.” The teachers involved in the collaboration provided ongoing professional development at the beginning of each staff meeting throughout the year. “Every activity introduced in PD is carried back to all classrooms,” says Harvey. My teachers view students in a new light.” Partners in Learning impacted the entire school building.

Of the need for a master’s degree, Harvey says, “You got to know your stuff to be able to engage our youth in these schools.”

Ashley Ponscheck says, “In Title I schools, the needs and challenges are so completely different and at times it can be isolating. To be able to be a mirror for each other has helped us grow personally and professionally.”

At Monroe High School, according to Dr. Harvey, 45 percent of the students are Hispanic, 35 percent are black, 11 percent are white, and 3 percent are other. Eighty-six percent of the students are economically disadvantaged. Harvey says, “it is very powerful to watch these students navigate being first generation high schoolers.”

Kayla Losh describes the implementation of SIOP (sheltered instruction observation protocol) in the classrooms — “an empirically-validated approach to teaching that helps prepare all students — especially English learners — to become college and career ready.” They set up a peer tutoring center and found other strategies to reach English language learners and limited English proficient students.

This included a field trip for the teachers to Siler City to meet with high school students and hear their stories and goals. “We were sitting in a circle,” says Jessica Hall, “and the students just talked. The degree of separation since these students were not our students allowed the students to be vulnerable with us.”

Chevy Coffey describes sitting in on a PLC at a middle school, thinking “I want to move the PLC from being a meeting to making it wrapped around student learning.”

The focus on the student also helped moved Coffey beyond thinking about “classroom management” to a understanding adolescent behavior. Now she “sets the expectations high and sticks to it.” Structure and consistency are key. Brad Breedlove, the director of secondary education for UCPS, smiles, “These teachers did not talk like this before.”

Coffey concludes, “My students know we have college class here after school. It sets a good example.”

Breedlove talks about just how powerful it was to shift the paradigm and have professors coming to the classroom. “Professors have to take that risk,” he says, “they don’t know what it is like to teach in a high poverty classroom.”

Dr. Ellen McIntyre says to the teachers and professors, “You are doing the hardest work there is and the most important work there is.”

Monroe Middle School

This is Steven Wray, the principal of Monroe Middle School with his teachers that participated in Partners in Learning, Amber Riddle and Amy Hall. Wray says, “I have never seen any teachers this motivated at the end of the school year.” He says these teachers come to school with their hair on fire.

Riddle says middle school students don’t have much self esteem. “We needed goals, we needed to work as a group, we needed motivation to change the school. This is why we come back to school everyday.”

Riddle teaches reading to 7th grade students. Many of them read at a pre-K level. “You are behind,” she tells them. “You are not dumb.” She says, “They hate to read. They hate school. They distrust their teachers. I am going to have to build a relationship with them if I have any chance of teaching them to read. One of my students was living in a park out of a garbage bag.”

“College did not prepare me for poverty,” says Riddle.

Hall has been teaching for 10 years. “This program,” she says, “has helped me rediscover who I am teaching. I feel like I have a connection with my kids this year that I have been missing. It has reinvigorated me to make a deeper connection with my students.”

“I am not just there to teach them math,” says Hall.

Dean McIntyre concluded, “This is the future of the education of our teachers. I need you.”

Union County Public Schools: A culture of innovation

Union County Public Schools: Classrooms of Tomorrow

Union County Public Schools: Partners in Learning Collaborative connects philanthropy, policy, and practice

Union County Public Schools: Talent matters

Editor’s Note: SAS and The Goodnight Educational Foundation support the work of EdNC.

Recommended reading