There is an effort underway at the University of North Carolina System to transform the way the state’s educator preparation programs do business. Sparked by inadequate results in getting North Carolina students reading on grade level by third grade, as well as the perennial shortage of teachers and prospective teachers, the system convened a series of higher education and pre-K-12 leaders to come up with a series of goals and strategies to improve how the state trains its teachers. It began with a report and has since been spearheaded by Julie Kowal, associate vice president for P12 Strategy & Policy at the UNC System.

At the heart of the System’s strategy is collaboration with the schools of education around the state as well as the leaders and teachers on the ground in the state’s K-12 system. The transformation isn’t meant to be a series of edicts, but a united group effort to make sure the state has the best teachers possible.

“We have tried lots of top-down mandates when it comes to teacher education, and yet in many ways we’re still not doing the job that we need to do,” she said.

Leading on Literacy

The impetus for the changes in the work began with a report commissioned by then UNC System President Margaret Spellings called: “Leading on Literacy: Challenges and Opportunities in Teacher Preparation Across the University of North Carolina System.”

While the report drills down on teacher preparation as it pertains to literacy in North Carolina’s public education system, its scope ranges well beyond that, touching on most aspects of the teacher preparation system.

The report suggested areas of improvement for the state’s educator preparation programs, particularly when it comes to teaching educators how to teach reading. But what the system needed to see real change was a group of experts who could come together and figure out exactly what should be done differently. That was the impetus for the Educator Preparation Advisory Group.

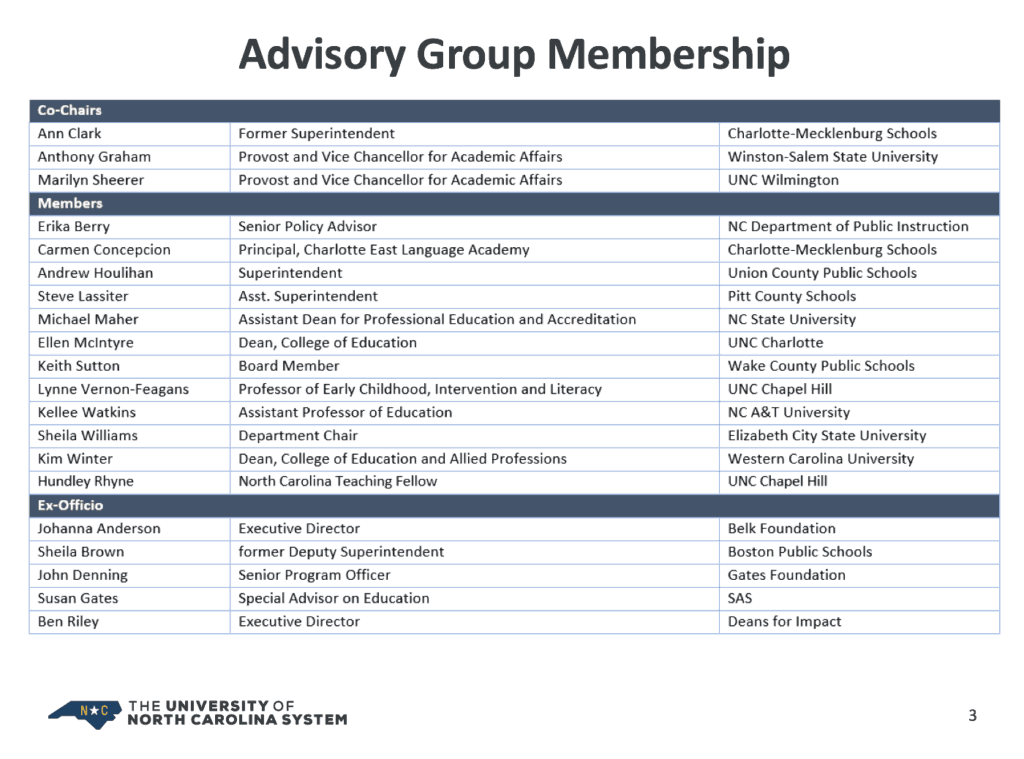

Kowal brought together education department deans, professors, district superintendents, nonprofit directors, and more, for a total of 20 people — half from higher education and half from the pre-K-12 system. They met over the past year and hammered out a series of goals, strategies, and metrics that will change the way teachers are taught.

According to a UNC System report on the group, this was their charge:

- Develop concrete, measurable goals for teacher preparation across the UNC System;

- Prioritize strategies to accelerate improvement in teacher preparation across the UNC System, beginning with recommendations from the Leading on Literacy report; and

- Define oversight and dissemination roles for the advisory group and the System Office to monitor and share information about programs’ progress toward those goals.

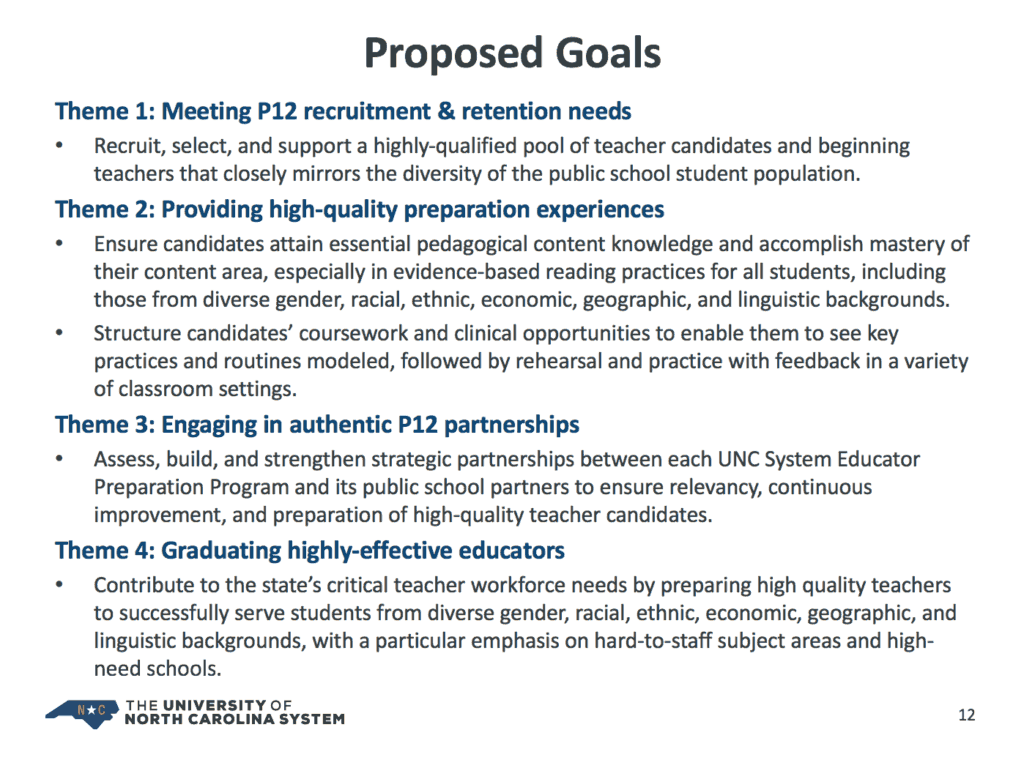

The goals

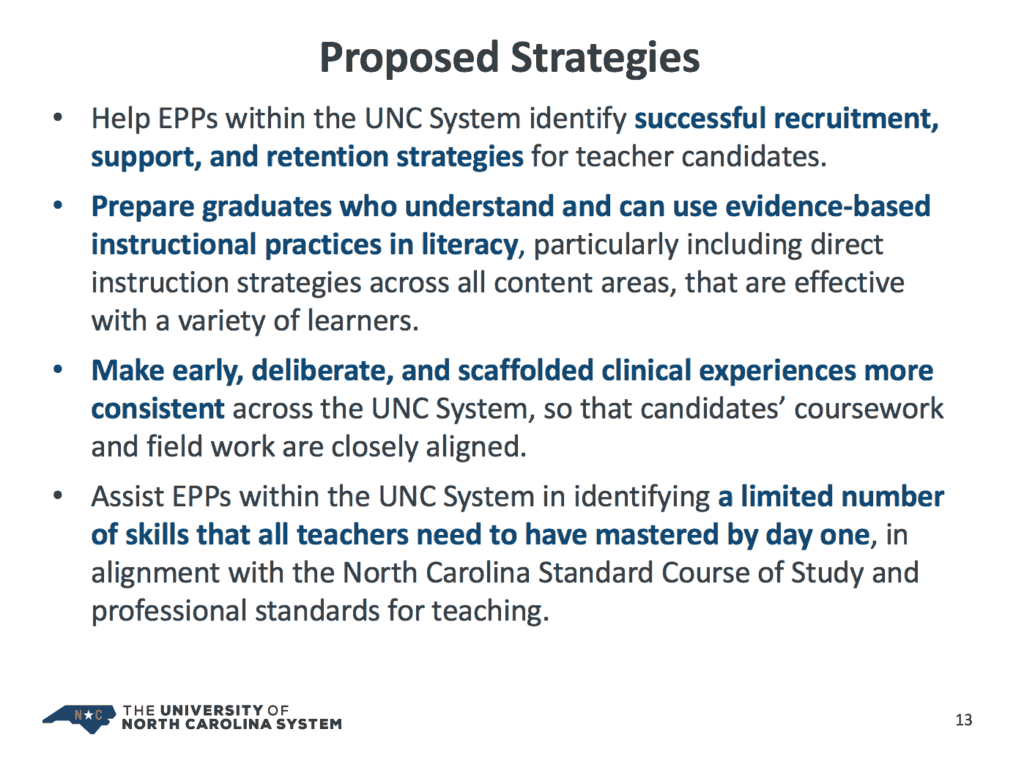

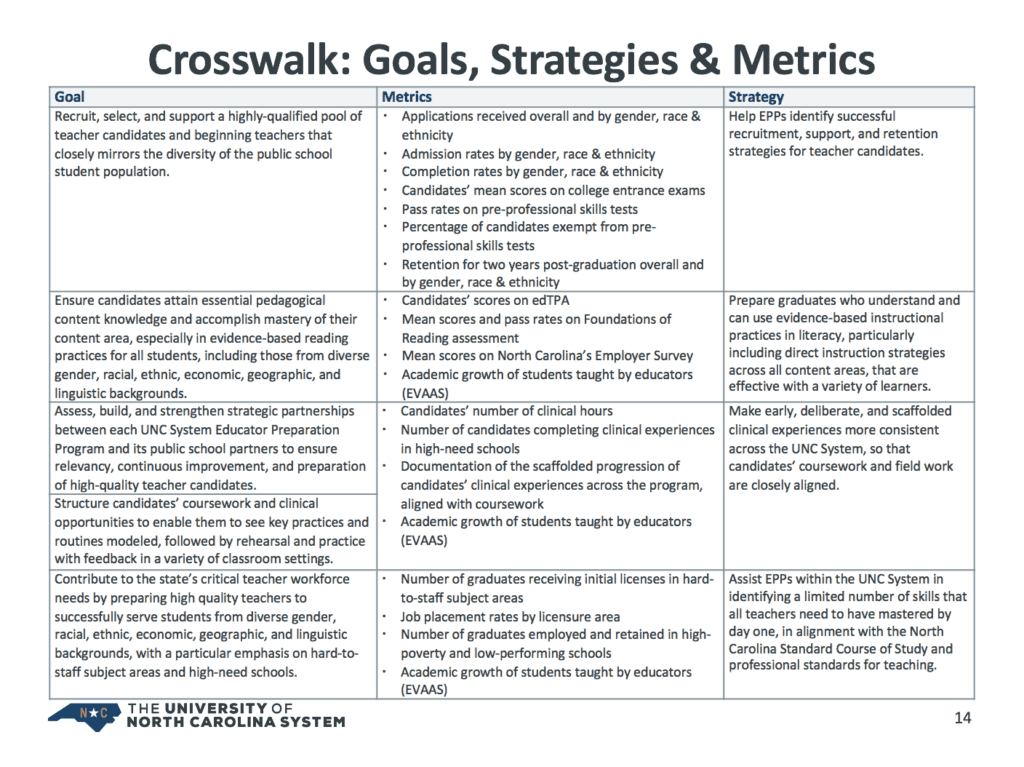

Kowal said that it’s not enough to have goals. There have to be strategies to achieve those goals, and metrics to measure whether they’re being reached. The advisory group met each month to figure out what all that should be and, earlier this year, drew up its conclusions.

Andrew Houlihan, superintendent of Union County Schools, said he came to the advisory group with a vested interest in the success of teacher preparation programs.

“I’m a product of a teacher prep program,” he said. “I was a NC teaching fellow and graduated from Elon.”

He said he has already seen positive changes in the ways that colleges of education have partnered with the pre-K-12 system over the last decade or so, but he was particularly happy to see such a diverse mix of people from both the higher education and public school realm on the advisory group.

“If the leadership of the colleges of education aren’t open to change, then nothing is going to matter,” he said.

He was keenly interested in highlighting literacy practices at educator preparation programs.

“One thing, and it really stemmed from the Leading with Literacy report, was a focus not just on K-3 literacy practices but really K-12,” he said.

One of the first concrete actions that has come out of the advisory group is the development of a Community of Practice focused on early learning and literacy.

A Community of Practice is a group of people from different institutions who come together to focus on a specific area that they think they can work on to come up with best practices for improvement. A Community of Practice focused on early learning and literacy launched in March. The idea is that different education preparation programs, working together, can brainstorm their experiences and practices to find the best shared strategy for tackling literacy and early learning. Many of the strategies laid out by the advisory group will ultimately turn into Communities of Practice, essentially transforming the UNC System educator preparation system into 4-5 distinct groups that engage each UNC institution in work on the issue they want to improve upon.

“My goal and my hope is that as a result of the work in that community you will have more and more best practices that will emerge,” Houlihan said before adding a note of caution. “What I hope it doesn’t become is just a committee or working group that just comes together to talk.”

Michael Maher, assistant dean for professional education and accreditation at North Carolina State University, was also focused on literacy when he came to the advisory group. In addition to serving on the advisory group, he is a Democratic candidate for the State Superintendent of Public Instruction in 2020 and vice chair of the Professional Educator Preparation and Standards Commission: the group charged with coming up with standards and rules for “all aspects” of educator preparation in the state.

Maher was critical of the Leading on Literacy report because, while it purported to focus on literacy, it also drew conclusions about other sections of educator preparation programs in the UNC System. When it strayed away from literacy, Maher thought the report got things wrong.

“Let’s get away from all this other stuff that purports to be wrong in the UNC System that I don’t think is really accurate,” he said. “When you had this big cumbersome report that had all these different things, you wouldn’t do anything well.”

Maher said his concerns were heard. The group started with 10 to 15 goals and even more strategies, he said, but ultimately whittled those down.

He said that being the vice chair of PEPSC has also been helpful. Whatever the UNC System does ultimately has to align with the rules and standards created by PEPSC and approved by the State Board of Education. If there isn’t an ease of communication between the advisory group and the commission, problems could arise.

“We’ve historically had this problem in teacher prep, where we have all kinds of measures and objectives and sometimes they align and sometimes they don’t. It’s very frustrating for teacher prep programs,” Maher said.

For Kellee Watkins, an assistant professor of education at North Carolina A&T, the collaboration between the UNC System and school district has been a highlight of her experience on the advisory group. Before she came to higher education, she worked in the Guilford County Public Schools.

“When I think about being able to hear the voices of people on the district level … to be able to hear people from the UNC system, to be able to hear people interested in growing foundations, that has been truly a good experience,” she said.

What now?

Even with a set of goals and strategies in place, the advisory group’s job is not done. More Communities of Practice are in the works, and in the meantime, the advisory group is going to continue to refine its plan. Advisory group representatives recently presented to a group of deans and department chairs from educator preparation programs across the UNC System and incorporated their feedback into its plans. The group is going to continue to do so by meeting with chancellors, provosts, educator preparation program faculty, superintendents, school board members, principals, teachers, and a host of other people with a vested interest in how teachers are taught.

At the end of the day, the changes taking place in the UNC System aren’t about top-down transformation, but about collaboration, according to Ann Clark, former superintendent of Charlotte-Mecklenburg schools and a co-chair of the advisory group.

“It’s really about full ownership of the opportunity to prepare our teaches to be successful,” she said.