Share this story

- OIC of Rocky Mount's president and CEO, Reuben Blackwell, acknowledges his organization "can't do it all. But we can do something in every single arena." Learn how @OICRockyMount goes beyond workforce development to support Blackwell's community.

- Since 1969, @OICRockyMount has provided workforce development in and around Edgecombe County. Over the last 30 years, it's also become a major provider of health services to the majority-Black population.

|

|

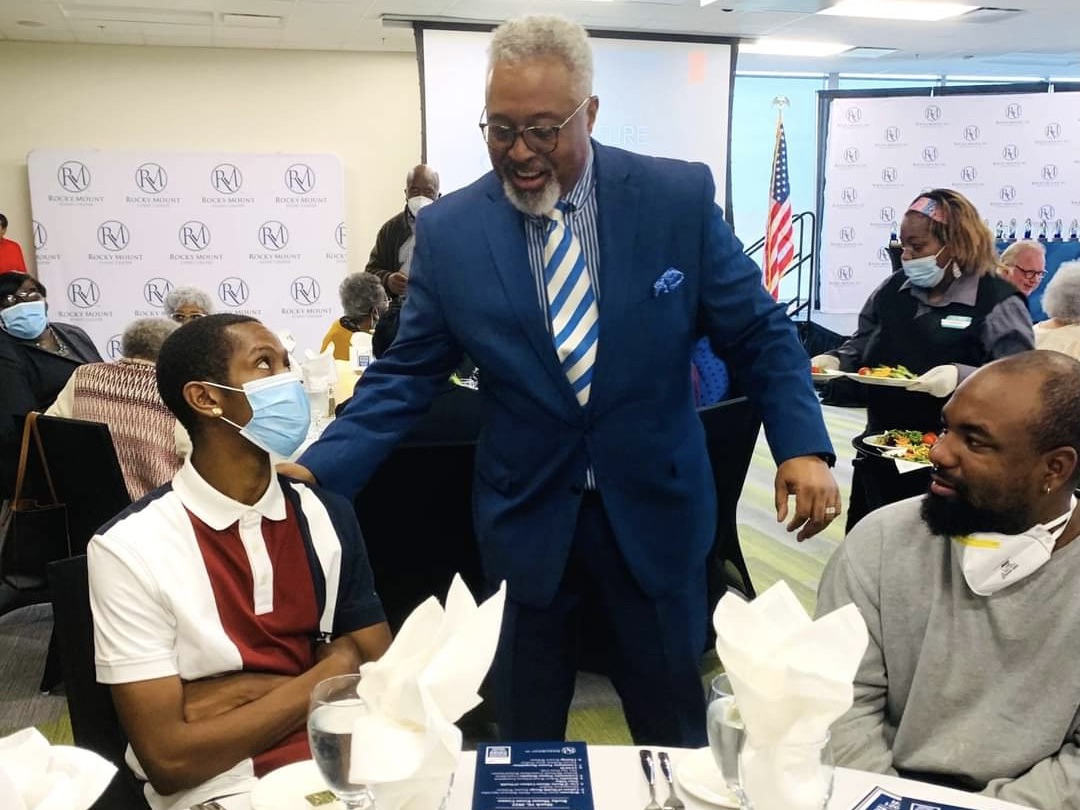

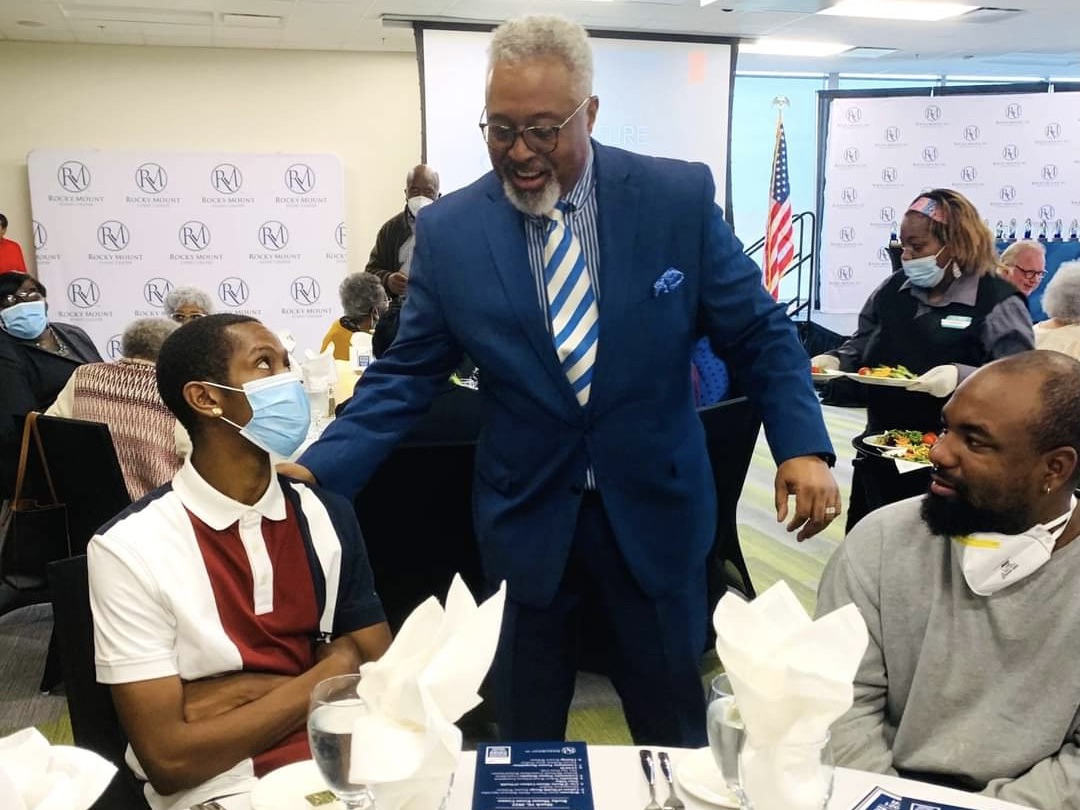

Reuben Blackwell wants you to know that Opportunities Industrialization Center (OIC) Rocky Mount is “unashamedly, unabashedly, a civil rights organization.”

As the president and CEO of OIC — and a Rocky Mount City Council member — Blackwell himself is unabashed about his advocacy for the majority-Black population of Edgecombe County.

“Edgecombe County is at the bottom of every measurement that is bad. We don’t have time to take our time,” Blackwell said at a presentation to the leadership team of Blue Cross and Blue Shield of North Carolina in February. “It’s already been 400 years.”

Founded in 1969, OIC provides workforce development for Edgecombe, Nash, Wilson, Halifax, and Northampton counties. Since the mid-1990s, its mission has expanded to include a variety of human services centered on meeting the socioeconomic and health needs of Rocky Mount’s Black community.

“I do consider myself an activist for civil rights because health care is a civil right, education is a civil right, economic opportunity is a civil right,” Blackwell said in an interview with EdNC.

The core of OIC’s mission has always been “helping people help themselves,” a message prominently placed on their promotional materials.

OIC’s education and training department operates a high school equivalency (HSE, formerly GED) program, in addition to offering courses through its integrated training academy (ITA). Through ITA, students can be trained in advanced manufacturing, health occupations, carpentry, and highway construction trades.

After students complete their education and training, OIC offers job placement assistance through its value added business services (VABS), which connects students with local employers.

Through VABS, OIC operates several in-house businesses to provide services to the community, including commercial and residential lawn care and construction, trucking, and warehousing. Jobs with these businesses are especially helpful for building the résumés of students who traditionally face challenges in finding jobs, including those who’ve been homeless or incarcerated.

While there are still systemic barriers to socioeconomic advancement for Black residents of Rocky Mount that date back 400 years, Blackwell and his team take a pragmatic approach to supporting students here and now. “If we can’t change systems, we shift and change what we can reach,” he said.

Rocky Mount is in both Nash and Edgecombe counties. Despite being referred to locally as the “Twin Counties,” Nash and Edgecombe have significant demographic differences.

According to the most recent census data, Black residents make up 41.3% of Nash County’s population, and 57.8% of Edgecombe’s. The poverty rate in Nash County is 14.9%. In Edgecombe County, it’s 24.1%.

The health disparities among residents of these two counties are also stark.

Based on data from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, Edgecombe County ranks 98th of the state’s 100 counties in health outcomes (how long people live and how healthy they feel). Nash ranks 62nd. For health factors — health behaviors, clinical care, social and economic measures, and physical environment — Edgecombe ranks 97th and Nash ranks 63rd.

It was these health disparities that prompted OIC to add health services to its workforce development model almost 30 years ago.

Young women participating in OIC’s workforce development programming were still facing a major barrier when applying for jobs, Blackwell said — they couldn’t get appointments with primary care providers when potential employers required a physical.

“There was a very dedicated striation between health care for poor people and health care for everyone else,” he said.

Blackwell explained that Rocky Mount’s health service providers had Medicaid caps, limiting the number of Medicaid patients they would accept. In some cases, patients were “frozen out of the practice” after missing three appointments because of the scheduling challenges common among parents of young children.

“Those young women and their plights opened up an opportunity for OIC to reconsider what our position in this community needed to be,” Blackwell said. “If we cared about workforce development, then we needed to care about every aspect of life that impacted the people that we’re training, preparing to change their life’s trajectory through a better education.”

He added, “I am glad that those young women did not sit and silently suffer.”

OIC built its first mobile health unit in 1995. It now serves about 10,000 patients annually through its three full-time primary care sites, a dental practice, a behavioral health practice, an urgent care center, two pharmacies, two mobile health clinics, a triage partnership with the Rocky Mount Housing Authority, and a community health education center.

As a federally qualified health center, Blackwell said, OIC receives funding from the Health Resources and Service Administration, in addition to payments from patients enrolled in Medicaid, Medicare, and private health insurance plans.

Much as with its other businesses operated through VABS, OIC’s health centers employ students who completed training in health occupations through its ITA program.

Blackwell takes pride in not only providing workforce development and health services, but in being an employer for the community — and not just for Black residents.

“OIC is the United Nations!” Blackwell quipped. “When you come into our workplaces, you’ll see people of all hues and tones and nationalities and ethnicities and orientations, because this is how the world is. We’re a global community. We just happen to be an institution that was created for, led by, and sustained by people of color, primarily Black people.

“A lot of times people think that being pro-Black means that you have something against white people. All people like myself ask is to give due consideration to the fact that we have systemic hurdles and challenges and barriers that have been imposed for one simple reason, and that’s because of who you were born to be, the color of your skin.”

Blackwell embraces the notion that OIC will continue to evolve as it has already done over the last 50 years. “We can’t do it all,” he acknowledged, “but we can do something in every single arena.”