|

|

Laquita Renwrick, a school social worker in Winston-Salem Forsyth County Schools, works with up to 200 students every year.

Her daily schedule varies, but often, she is driving students to doctor’s appointments, researching child care options, or buying diapers.

Renwrick’s official title is school social worker for teen parents and families. Her job is to support pregnant and parenting teens in the school district.

In 2020, nearly 8,000 North Carolina teens aged 15-19 had a reported pregnancy, according to data from the N.C. Department of Health and Human Services.

Organizations across North Carolina exist to support these pregnant and/or parenting teenagers. Some of these supports are in the school system, some are alternative schools, and others are community-based organizations.

The teen birth rate in North Carolina has decreased tremendously – falling 62% from 1996 to 2015 – over the past few decades. Kristen Carroll, reproductive health branch head for the N.C. Department of Health and Human Services (NCDHHS), said that teen pregnancy work in North Carolina started in the 1980s. Teen pregnancies started to decrease in the following decade, she said, and have declined steadily among all racial/ethnic groups.

Contraceptive use, adolescent behavior, and abortion access have all played a role in this trend.

In the wake of the overturning of Roe v. Wade last summer, the North Carolina legislature just successfully passed Senate Bill 20, which places restrictions on in-clinic abortions after 12 weeks and medication abortions after 10 weeks.

This law could have broad implications on the reproductive health of teenagers in the state.

In 2020, 1,855 North Carolina teenagers aged 15-19 had an abortion.

Renwrick said because of the higher rates of homelessness and lack of support systems for pregnant teenagers, she thinks this population would be one of the first and most impacted if access to abortion in the state is restricted.

Here’s a deeper look at how some N.C. schools and nonprofits are providing support to pregnant and parenting teenagers right now.

School social workers

Renwrick has worked in her position since November 2021. She works with teens who are enrolled in the school district as well as teens who aren’t, as long as they are under the age of 21 and working toward re-enrollment.

Forsyth County had 315 teen pregnancies in 2020.

When Renwrick finds out a student is pregnant, she meets with them to explore options –having an abortion, keeping the baby, or giving it up for adoption. She provides guidance for whichever option the student chooses and also works with them on a plan to tell their parents or guardian if they haven’t yet.

Day-to-day, she travels between schools to check in with students, and is contacted by students or staff members for specific needs or concerns. She provides supportive counseling to students, home visits, and transportation to appointments if needed. Her goal is to make sure students stay enrolled by helping them get accommodations like extra bathroom breaks or schedule flexibility, or seeking out alternative schooling options.

Some of the teens she works with are experiencing homelessness – unmarried parenting youth have a 200% higher risk of reporting homelessness – so she works with them to provide extra security blankets, like making sure they have food from the district’s food pantry and suitable clothing, and intervening in domestic incidents.

Occasionally, she works with teen parents who are incarcerated and need even more support.

“Advocacy is a big part of my role,” she said. “And of course, working together with our school staff to make sure needs are being met for the students and their families.”

Sonya Rush, the special high school populations coordinator for High Point Central High School, only works at one school but works with nine different populations at the school including pregnant and parenting teens.

This year, she helped the school start a baby closet that provides cribs, strollers, car seats, diapers, and baby clothing to parenting teens.

Rush collaborates with the YWCA of High Point to meet with teens and talk about topics like the stages of pregnancy, parenting, finances, or grades. Sometimes former teen parents or single moms come to discuss their experiences.

The YWCA of High Point has a doula that the students have access to, and High Point Central High School also has a staff member who is trained as a doula and is currently getting credits to be a lactation coach.

A project Rush is currently working on is to build a lactation room in the school for pregnant students and teachers. She hopes to create this room over the summer to be open for use next school year.

Rush also monitors students’ grades, facilitates health checks with the school nurse, and works with teachers to be flexible or to help teens find tutors. This school year, Rush worked with 12 teens. Some stay in traditional school, or enroll in local alternative schools like Brittain Academy.

School-based alternative programming

Steffanie Lewis has worked with Safe Journey, a school-based program that serves parenting teens in Mecklenburg County, for 10 years. She started as a case manager and has been program director for the past four years.

The goal of Safe Journey is to assist teen parents with completing high school and delaying additional pregnancies. Participants must be full-time students enrolled in Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools (CMS), and can be enrolled during pregnancy or while parenting a child up to age five. There’s also a requirement that teens who participate be on some type of birth control.

Safe Journey provides child care subsidies to participants.

Lewis said Safe Journey started in 1998 as a response to the high teen pregnancy rate in the 1990s. While the program started by serving 20 teens a year, now it works with 100 teen parents annually.

Five case managers work across 13 CMS high schools, providing support and advocating for students. The case managers use Parents as Teachers-based curricula to facilitate learning about pregnancy, parenting, child development, and mental health for their teen parents through home visits. Safe Journey provides health screenings for children and access to medical doctors to provide a safe space for teens to ask questions.

“Our thing is just to be there for them, walk alongside them in their journey, and make sure they know they have somebody who cares about them and their child,” Lewis said.

She said since the pandemic, she’s seen more teen parents become non-traditional students because of the flexibility in virtual schooling. Some teens go to local charter schools or take classes through community college.

Community nonprofits

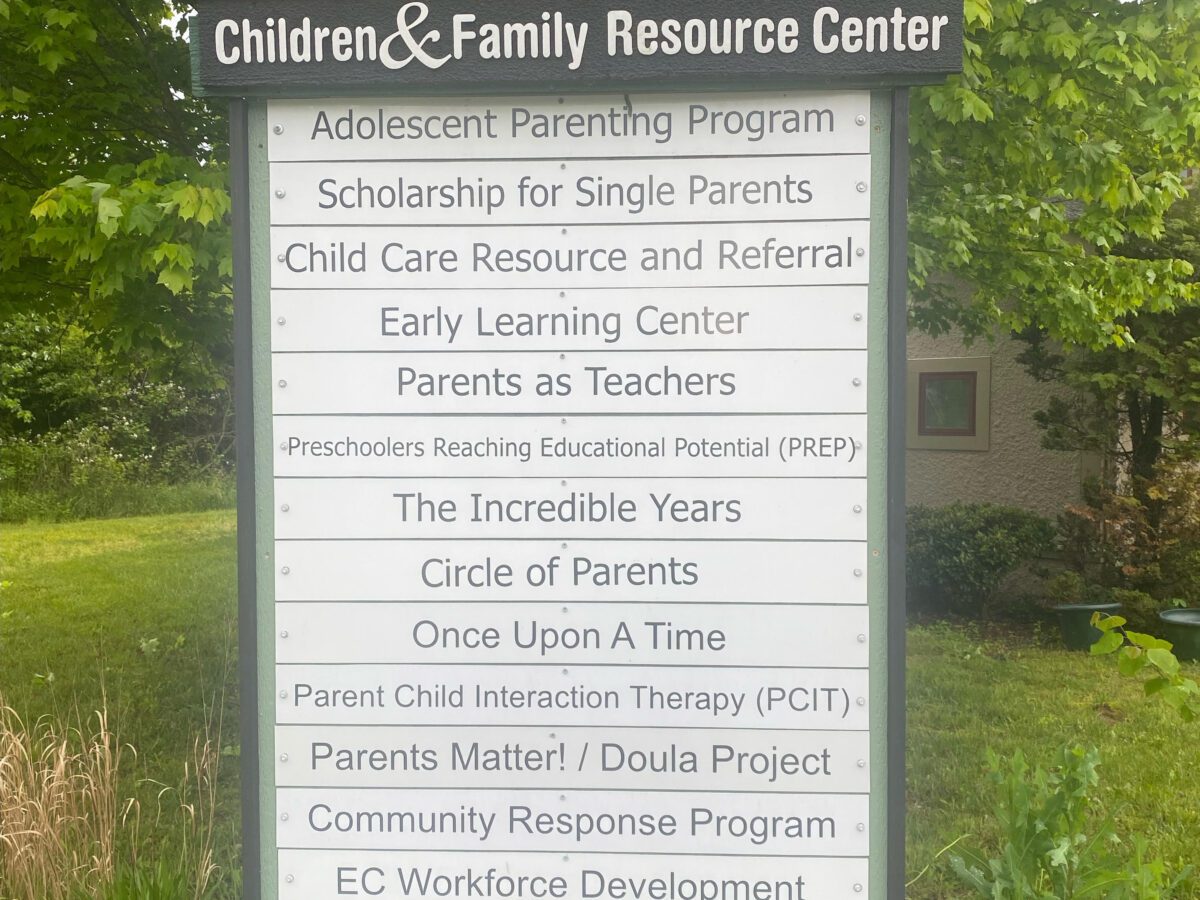

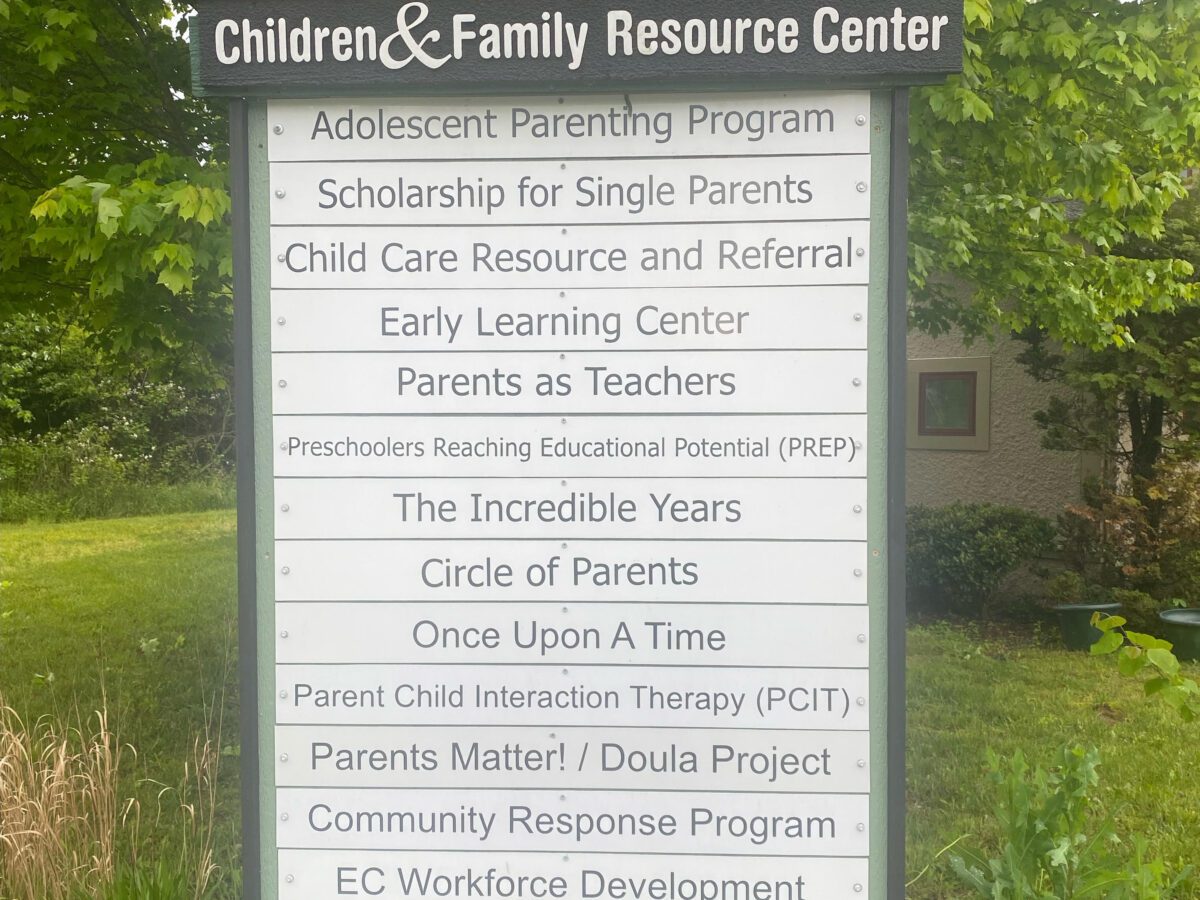

The Children and Family Resource Center in Hendersonville runs an adolescent parenting program that has been around for 25 years. The program serves Henderson County teenagers that are pregnant or parenting until they turn 20.

Shelbie English, the center’s maternal health coordinator, works with two other coordinators to serve up to 24 teens at a time.

The program focuses on making sure students graduate school and it also provides child care resources and referrals, home visits, parent support groups, and education on childbirth, lactation, and childhood development. Coordinators work with students to go to community college, find a job, or finish their GED, and help them sign up for supplemental programs like food stamps or WIC (Women, infants, and children).

In order to prevent or delay additional pregnancies, English said the center also facilitates reproductive education, including a sex education class for teen parents.

English said students often come into the program not knowing that condoms help prevent sexually transmitted infections, or with mixed messaging around consent and relationship negotiation.

The adolescent parenting program is funded by the NCDHHS’ Teen Parenting Program Initiatives (TPPI), which funds programs in North Carolina that prevent teen pregnancy and support teen parents.

Carroll, the NCDHHS reproductive health branch head, said TPPI provides application-based funding as well as technical assistance, consultation, training, and support for community programs.

She said the goal is for programs to be able to continue even after they are no longer funded by TPPI, so TPPI looks to fund programs that prioritize community and sustainability.

“They’re really the champions out here doing this work,” she said. “So many of them are very creative in how to connect with people. And even when challenges arise, they still find unique ways to make it happen.”

This is part of a series of stories about reproductive/sexual health resources for teenagers. You can find the first story in the series, which includes a map of resources, here.