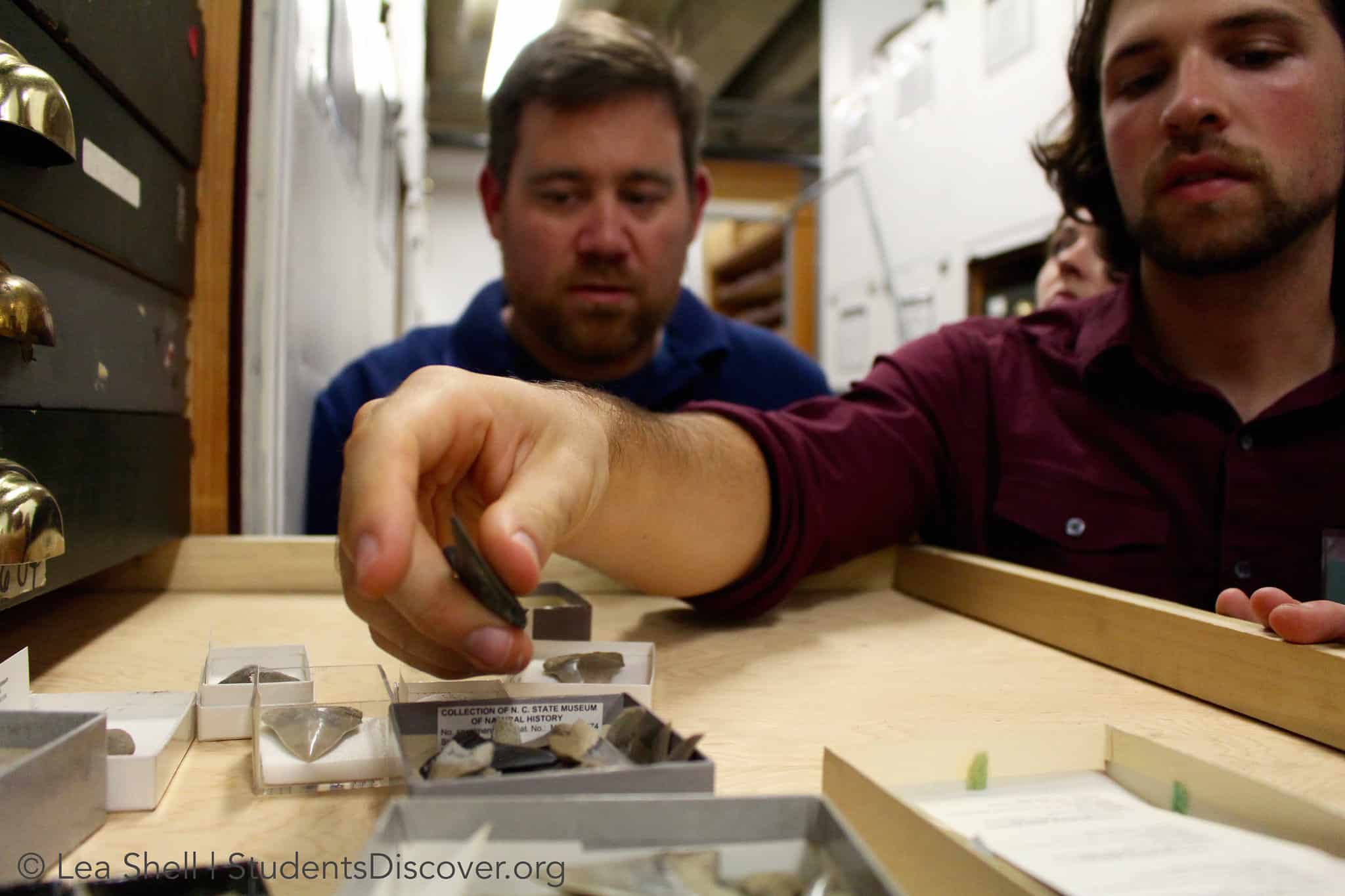

There are no words to describe just how incredible and transformative my summer internship in the Paleo Lab of the N.C. Museum of Natural Sciences has been. Over the course of three weeks, I learned tons about sharks, their teeth, and their jaws. I had the opportunity to travel with the two other 2015-16 Kenan Fellows on my Students Discover team to Florida where we took more than 1,800 pictures of individual shark teeth.

I also had the privilege to accompany my mentor, Dr. Bucky Gates, on a real life paleontology dig in Utah as an extension of my Kenan Fellows experience. I am so excited and thrilled to have been offered the chance to literally DIG UP DINOSAURS!

The 10-day adventure in Utah gave me a much better understanding of geology and paleontology ─ two things that I never imagined I would have expert knowledge in or be able to teach my students about. Since the start of my teaching career, I’ve know that I wanted to integrate the arts with the other subjects, but as an art education student training in other disciplines or finding ways to connect between the disciplines was extremely lacking. Interning with Dr. Gates at the Museum of Natural Sciences helped me to fill that gap.

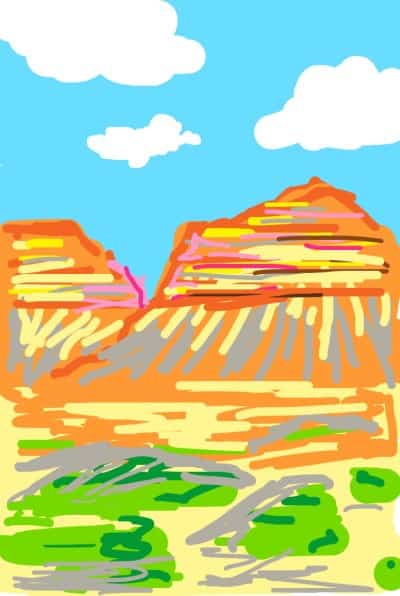

Day one of my Utah adventure was almost all traveling. During the long drive I got to see the breathtaking landscapes of Colorado and Utah and Dr. Gates explained some of the geology of the area, along with why paleontologists frequent that particular region of the country. Sedimentary rock layers in this part of the country are crucial for understanding fossil records and geologic time.

Once we got to camp, set up our tents, and the stars gleamed in the night sky, the realization of just how far away from civilization we were sunk in. And I was able to brace myself for the adventure to come. Our mission for the trip revolved around quarrying and prospecting. Quarrying involves going on a relatively short hike to a pre-established site where dinosaur bones had already been discovered. There, we unearthed them by slowly digging away at the rocks surrounding the bones, exposing them enough to cover them with plaster and extract them from the site. Prospecting involved looking for new sites to quarry. This entailed long hikes through wilderness, across desert, and up and down mountains looking for bits of bone on the surface hoping to find some or most of skeleton.

I was lucky enough to have an almost an even split between prospecting and quarrying during my time at camp. Personally, I preferred the novelty and discovery that came with prospecting. There’s just something indescribably awesome about knowing that you are the first person to ever have laid eyes on something that is millions of years old. Plus, hiking through Utah’s landscape let me experience some truly beautiful sights, that I never thought I would have a chance to see.

A few days after our arrival, I saw some petroglyphs on rocks that were carved by ancient desert people, and the correlation between art and archeology became evident almost immediately. It was my first time seeing ancient art history in person. As soon as I saw them, I knew I wanted to incorporate what I saw into my art history lessons on Native American and prehistoric art.

On our last day a huge thunderstorm rolled in transforming the desert into a muddy, slippery wasteland. After everyone dried off, we gathered in the main tent and some of the campers made sculptures from the desert mud. At that moment I realized something that I’d never thought of before ─ what my profession is about for the students who will never become artists. So often the art made by “non-artists” is about joy. It’s about filling the sadness that stems from boredom with the joy of creation. Their art will not sell for millions of dollars, but the act of making it brightens their day. As an art teacher, that realization made me so happy.

Before Utah, I liked adventuring, hiking, and backpacking. Now I LOVE it and I can’t wait to go back, to keep exploring and to find out more about myself in the process. I want to use those future experiences to discover or study something new, maybe not paleontology, but what about a field experience in botany or entomology, or even in anthropology? I am interested to see how I can improve as an art teacher by studying and learning from professionals in other disciplines and I think full-blown field experiences would be an excellent way to do that.

Since the beginning of my internship at the Museum of Natural Sciences, I was excited about learning to think like scientists, but it didn’t occur to me until almost the end of my experience and began to develop after our lesson that I am a scientist. I’ve never thought of myself as a scientist ─ an artist sure, but not a scientist. Until I realized this must be how our students feel a sense of disbelief with a twinge of excitement and hope. This fellowship has solidified how I feel about creating lessons that inspire curiosity and invigorate students into asking questions to dig deeper. Like my experiences in Utah, I want to create experiences for my students that they are never going to forget.