When I first started teaching as a high school science teacher at Warren New Tech High School with Teach for America in Warren County, it amazed me how small the school was. All 150 of our students fit into a single hallway, 10 classroom building with four additional classrooms found in a modular portable building only a short walk outside. There are two teachers per subject with the majority of teachers having three preps. However, I quickly learned that this was not uncommon in Warren County, which contains three high schools for a total of roughly 500 high school students.

It is a true rural county with a population density of around 50 people per square mile, compared to Wake County or Mecklenburg County who have population densities of roughly 300 people per square mile and 550 people per square mile, respectively. You’ll find rows of once great tobacco, a staple crop of the county, that once made Warren County the wealthiest in North Carolina. But its continuous focus on agriculture and lack of development in other financial investments brought Warren County to where it is today: one of 20 poorest counties in North Carolina with a per capita income of about $17,850 compared to the North Carolina average of $24,750.

Its largest employer is the school system, where educators work tirelessly towards teaching a majority of students who are one or two grade levels behind compared to the rest of their North Carolina peers. With this knowledge, it allowed me to have a better understanding of my students, where they come from, and what kind of experiences and perspectives they bring into my classroom.

My childhood education was a bit different compared to the one that I am currently working in. I grew up in suburban Victor, New York, a small town just outside the city of Rochester that has been growing tremendously over the past 15 years. When I was in first grade, the entire class population was a little more than 150 students. When I graduated high school 12 years later, my class size had grown to 300 students. With this change in numbers came changes happening to my town. Farmland and wooded areas were replaced with neighborhoods and shops. Close access to Route 90 and Route 490 made travel into Rochester easy.

But I think a large contributor to the influx of students was the education that the Victor Central School District provided. With strong results and easy access to resources, I first started to notice the opportunity we had when starting 7th grade year it was a requirement to take technology classes, art classes, and music classes. As well, all of the science classrooms had a second room attached for lab space, something I was not used to. These opportunities continued into high school, taking five technology classes and diving deeper into science with taking AP Chemistry and AP Physics.

Coming to Warren County, these experiences were very far from a possibility for my students.

The science classes currently offered are the requirements, Earth and Environmental and Biology, as well as Chemistry and Physics. However, at most other high schools in eastern North Carolina, including the other two high schools in Warren County, Chemistry and Physics are combined into Physical Science, and students only need three science classes to graduate.

We also have two technology classes, one focused on digital media and another on basic engineering, but this is uncommon compared to anything else in Warren County or Eastern North Carolina. Warren New Tech High School is a part of the New Tech Network, a nationwide collection of high schools founded on the idea of project-based learning initiated by the Bill and Melinda Gates foundation. Because of this New Tech Network, our students have the opportunity to experience education by completing more projects, doing more presentations, and collaborating with their classmates more than you would typically find at a high school. However, where this education falters for the students is the lack of up-to-date technology available for the students to use to make 21st century results and the depth of knowledge and understanding that the students experience.

Whether in the science or technology classroom, student experiences with the latest technology look like Chromebooks and calculators that are over five years old. Lab equipment looks like something that was donated from another school who received new equipment before 2010. Lab tables have all the gas nozzles and sinks, yet no piping to drain the water, or tanks to provide the gas. It is a school that looks like it has met all of the requirements, but when digging deeper into the details, it is easily seen that these students are not receiving the 2019 education that they deserve.

With improper supplies, it makes conducting laboratory experiments a figment of imagination—rare occasions that slightly introduce students how to conduct an experiment and follow the scientific method. Lost for the students are the inquiries about why things work, and instead filled with expectations of “What do I need to learn to pass the final exam?”

Another reason for this is that students are just taught the “what” of science, not the “why.” They haven’t been asked to explore in detail, or taught in detail, the studies and findings that prove everything that we know about. They go through class taking their notes and memorizing the content, never questioning why things are the way they are. The only time that these moments of questioning occur are when they are introduced to something new. The best way I’ve found to witness the students’ excitement and wonder is when we have conducted laboratory experiments with the resources we have. But because of the limited resources, what they get to experience is only just the surface of all the incredible explorations that science and technology can provide.

Thankfully, I had the opportunity to bring my students to Biogen to conduct a lab experiment that showed them more of the outstanding potential that science has to offer.

The Biogen Experience

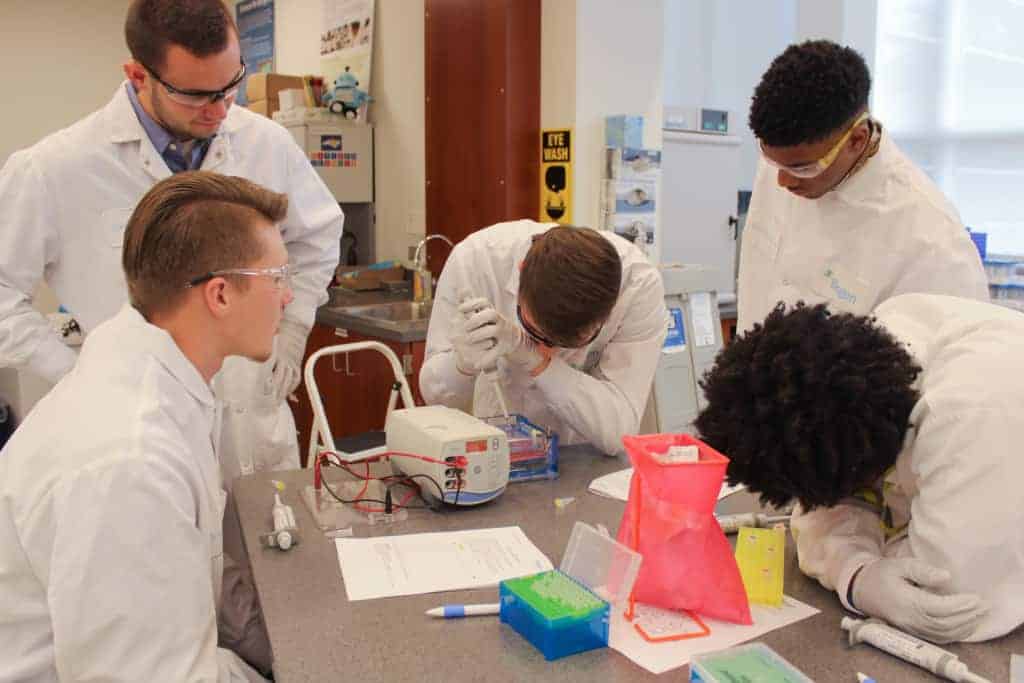

In early December, my students had the opportunity to travel to Biogen’s Community Lab in Research Triangle Park to conduct a lab on hemophilia — doing a quick lab on the human genome and developing a better understanding of how enzymes work with DNA. In the lab, the students had the opportunity to work with the latest technology in micropipettes and gel electrophoresis machines. And more important, they were given the questioning and learning of why everything is working the way it does.

The Biogen staff did a fantastic job going into the necessary details and findings to prove why everything that we were doing was happening. At the end of the day, the excitement, wonder, and questioning were there. Students were focused on the lab that they had conducted and wondered why we didn’t do those same things at school. They had been given some taste of what possibilities science provides during my class lessons and labs, but they knew after going to Biogen that there was so much more to learn.

Students’ science education has allowed all of the incredible technological advancements that we have today. Science classes build problem-solvers, critical thinkers, and inquirers that will continue to create our next generations of scientists, engineers, entrepreneurs, inventors, and so many more crucial careers that move our nation forward in the information era. But when the science education in our school systems varies because of resources and quality teachers, it creates a disparity in opportunities to be a part of the frontline of technological development.

Every student has the same potential to do incredible things, but not the same opportunity. And when those opportunities are not equal, it creates a gap that only continues to grow. The zip code that a child is born into should not be the determining factor of their future, however, unfortunately that is the truth. If we as a nation want to realize the full potential of everyone, then those same opportunities should not just be given to a select few. If we want to truly make America the nation of possibilities, then there are changes in access to science education that need to be made.

This perspective is the first of our Biogen series this week. Follow along at https://www.ednc.org/category/biogen/.