Madison County Schools is a small, rural district covering 450 square miles in western North Carolina. Led by a superintendent who grew up in the county, this district is doing an incredible job providing data-informed, personalized, rigorous instruction and intervention.

But it costs money.

School districts receive funding to serve their students from a variety of sources, including their county commissions, state government, federal government, and philanthropy.

We looked at how this district invested federal relief funds and how those investments connected to student growth.

“All of that funding went exactly where it was needed,” said Jennifer Mills, the principal at Hot Springs Elementary.

The district estimates it would cost $1,000,000 annually to fill the looming federal funding cliff.

During our trip to Madison County, one thing became clear: regardless of the source of funding, an investment in this school district is an investment in students, the workforce, leadership, the economy, and the future.

Madison County by more than the numbers

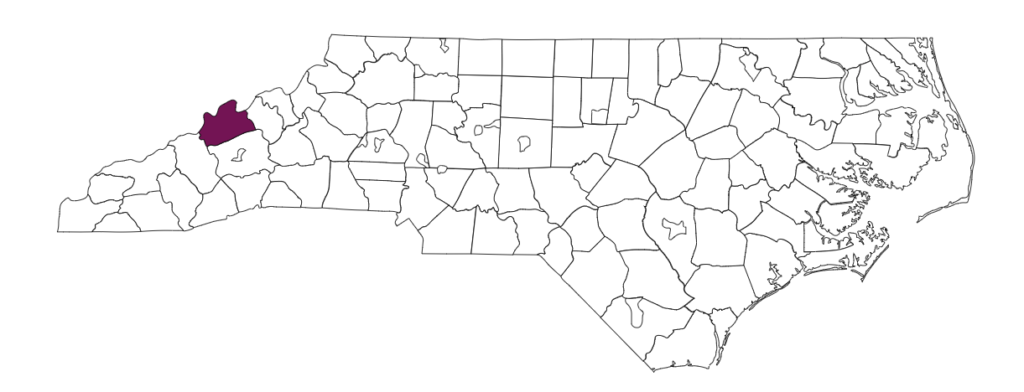

Madison County is about 30 miles northwest of Asheville.

For those visiting, it is a land of hiking, white water rafting, and hot springs.

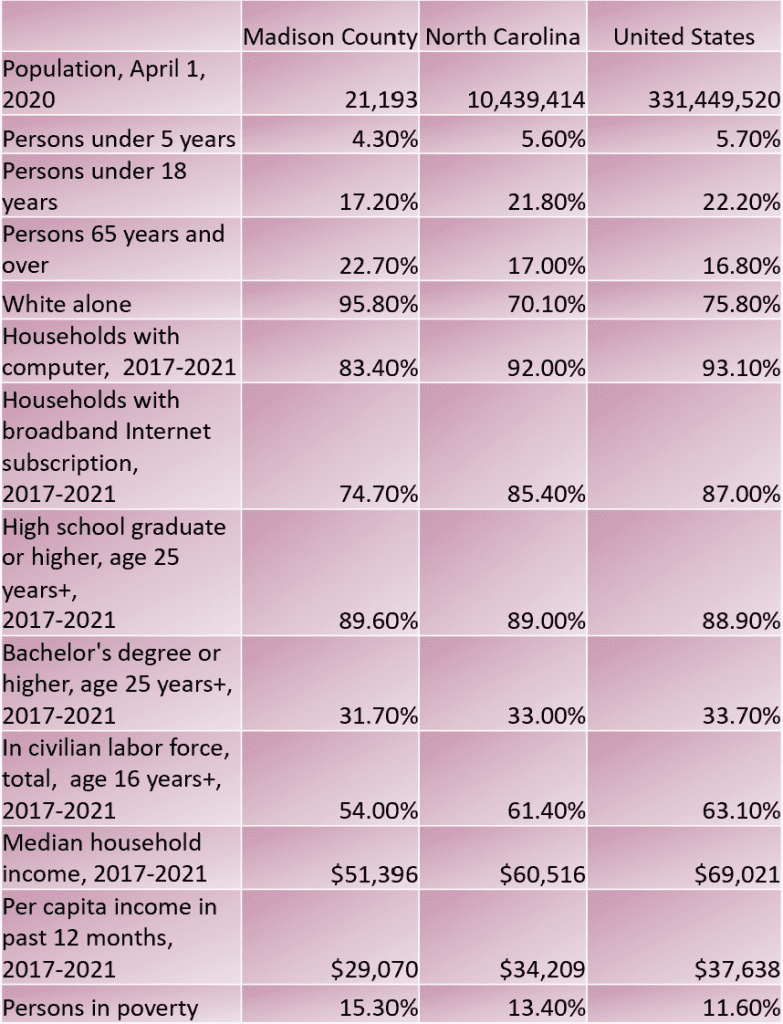

If you look at the demographics of Madison County, it is whiter, older, poorer, and less educated than the population of North Carolina and the United States.

The state’s tier designations can limit sources of funding for a county like Madison. “The 40 most distressed counties are designated as Tier 1, the next 40 as Tier 2, and the 20 least distressed as Tier 3,” according to the N.C. Commerce Department.

Madison County is designated Tier 2. But if you get on a school bus and drive the county, you will quickly realize that there are pockets of high-end housing and property values near the Buncombe County line and also scattered throughout the county for second homes.

And then there is the rest of Madison County. Communities like Laurel, Upper Shut In, and Spring Creek are among the most economically distressed in North Carolina.

To those who call Madison County home, however, it is rich in culture, language, tradition, and a profound sense of place.

Meet Debbie Chandler. Over the course of her career, she served as a bus driver and an instructional assistant. She has also worked with PAGE, a summer program that explores the nexus of literacy and STEM to equip girls with the skills they will need in the 21st century global workforce.

Chandler’s grandmother was Dellie Norton, a historic artist of the Blue Ridge National Heritage Area, known for singing ballads of English and Scottish heritage on her front porch.

Like Chandler, most people you meet in Madison County have deep ties to the schools, including Superintendent Will Hoffman. Hoffman grew up here before going on to serve as principal of Hot Springs Elementary and Brush Creek Elementary.

That’s because Madison County Schools is the largest employer in the county, followed by Ingles, the county government, and Mars Hill University.

These schools anchor these communities and this county

This school district includes six schools:

- Brush Creek Elementary, built in 2002 with renovations in 2004 and 2015;

- Hot Springs Elementary, built in 1960;

- Mars Hill Elementary, built in 1951 with renovations in 1956 and 2002;

- Madison Middle School, built in 1990;

- Madison High School, built in 1971 with a renovation in 2009; and

- Madison Early College, built in 2018.

All of the schools in this county received a B or C on their 2022 school performance grades. There are no schools designated as low performing.

In the 2022-23 school year, the district is serving 2,107 students.

The per-pupil expenditure (PPE) in Madison County Schools is $14,868.92: $9,822.47 in state funding (18th highest in North Carolina); $2,622.82 in local funding (30th highest); and $2,423.63 in federal funding (31st highest) — the 19th highest PPE overall in the state.

The district receives state allotments for being low-wealth and small, for disadvantaged students, children with disabilities, and limited English proficient students.

According to BEST NC, the COVID PPE was $808 per pupil in 2020-21.

Of the dollars coming in, 78.4% are spent on salaries and benefits, 8.7% on supplies and materials, 5.7% on purchased services, 3.8% on central office, and 3.4% on instructional equipment.

The teaching corps in Madison County Schools have performance scores totaling 10% highly effective, 75% effective, and 15% needs improvement.

In our travels at EdNC, we are always on the lookout for innovation. Sometimes innovation bubbles up from classrooms and schools. Other times, it is pushed into classrooms and schools by the district leadership or the state. Here it seems to be a strong mix of both, reminiscent of what we saw in Singapore.

Madison County Schools has a motto of “making it happen” and that is exactly what they do, providing an amazing return on their community’s investment every year.

— Jeremy Gibbs, DPI’s Regional Director, Western North Carolina

As the pandemic becomes endemic and federal funds sunset, Hoffman worries about how innovations across the district that have led to even higher student outcomes can be sustained.

You can learn a lot about a place and what is valued collectively in different communities by visiting schools.

Take a look.

Hot Springs Elementary

‘I feel like it’s home.’

No warmer welcome exists in North Carolina than the one offered by Julius, a second-grader at Hot Springs Elementary.

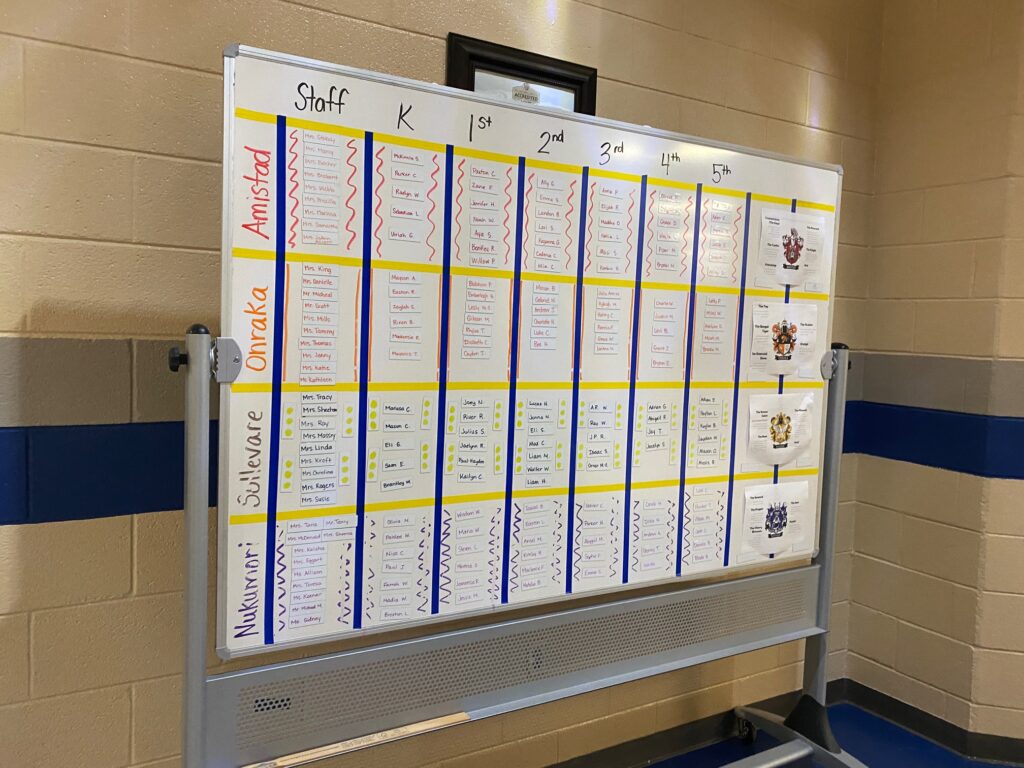

Students across grade groups are organized into four houses.

This is a school where more than one teacher drives an hour each way every day from Tennessee to teach.

Fifth grade teacher Alisha King taught for four years in Tennessee, but now makes the long commute to Hot Springs Elementary. Why?

“I love the kids, the parents, the faculty,” she said. “Every one is welcome here. I’m thankful I can rely on team members. We really work together as a team.”

King’s fifth-graders don’t want to leave this school and are quick to tell you how much they love it too. Their why?

They all have jobs. At the beginning of fifth grade, they collectively set the rules and expectations for their class, but they also organize themselves in teams to put the flags up, handle morning announcements, take out the recycling, and lead school assemblies.

Principal Jennifer Mills said that nothing increases these students’ maturity more in preparation for middle school.

Thanks to the Dogwood Health Trust, the school has a new, ADA-compliant playground with a walking track and shade that serves the whole community.

The critical need for pre-K

When the local organization running the pre-K program in Hot Springs shut down in 2019, the Madison County Board of Education in partnership with the Madison County Commission and Smart Start sought to re-establish and fund this critically important program.

The shut down left the communities in and around Hot Springs without any services for 3- and 4-year-old children.

“Hot Springs is our highest need school in the district, qualifying for Title I services [and] Community Eligibility Programming. It has the highest percentage of exceptional children and the lowest socio-economic designation,” said Hoffman.

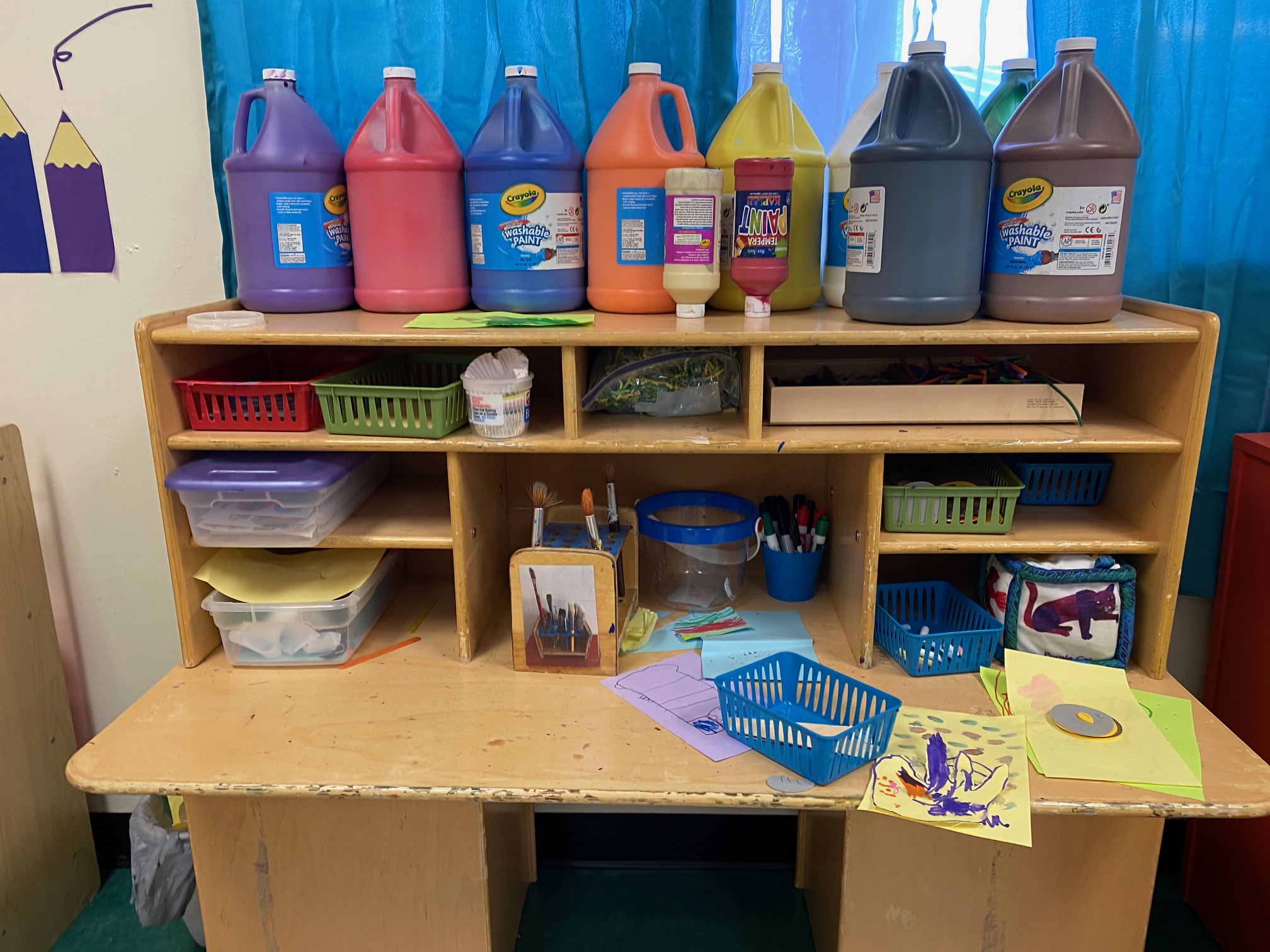

The early child care program is housed in a building adjacent to Hot Springs Elementary. Funding was needed to ready the building, for three teachers (enough to serve exceptional children and stay open if one teacher is absent), curriculum, assessments, stipends for college coursework for teachers, and professional development.

Early child care allows students to grow academically, physically, emotionally, and socially, and so Hoffman believes expanding and supporting pre-K needs to be easier for districts. He cited challenges including start up and ongoing costs; bureaucratic complexity; over-regulation; more stringent facility requirements; and overlapping, local initiatives with competing priorities.

“There is a disconnect here in that what we do for our 4-5-year-olds in kindergarten classes should not be so different than what is required for a safe space for 3-4-year-olds in a preschool classroom,” said Hoffman. “Why does this have to be so difficult?”

Mills said, “I wish you could see night and day the kids that actually look like students coming into kindergarten having been through a structured program with socialization.”

Growth for all kids

“A lot of mountain school systems have done very well historically,” said Jeremy Gibbs, DPI’s regional director in Western NC. “It’s a little bit different in Madison County.”

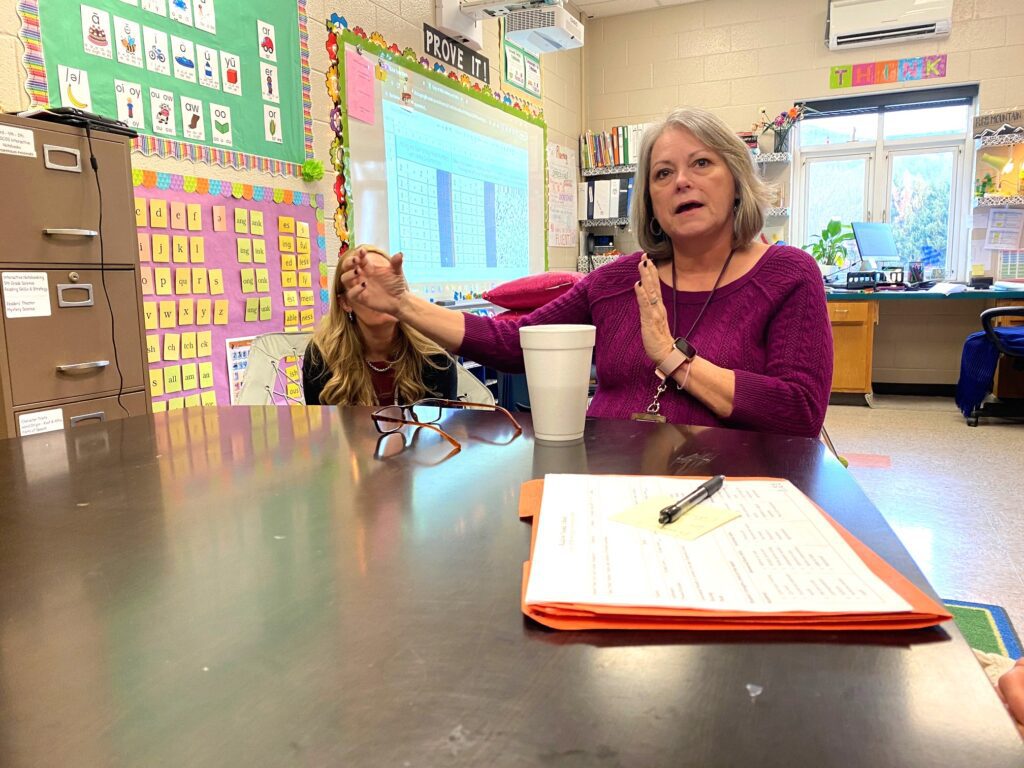

“Madison County hasn’t had the luxury to just try things,” he said. “With limited resources, they have to be intentional. Combined with a real expectation that all kids are going to get pushed.”

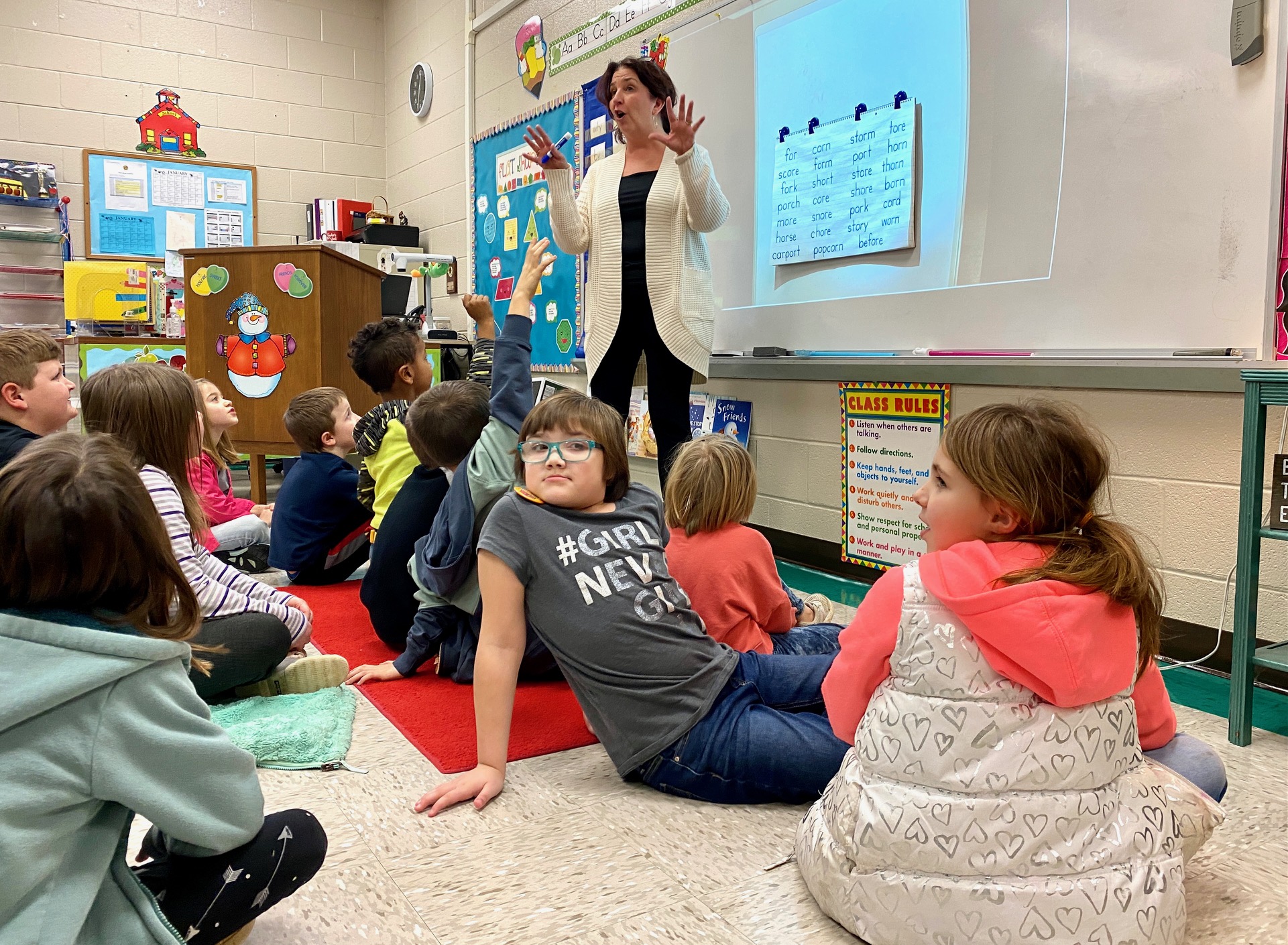

Thanks to federal funding available during the pandemic, Hot Springs Elementary has a K-2 interventionist and a 3-5 interventionist. Students get 45 minutes of reading and 30 minutes of math intervention four days a week. The interventionists are master teachers. On Fridays, they look at assessment data, re-group students, identify what needs to be honed in on in the next week to fill gaps, and pass that information off to the teachers.

These educators don’t want there to be a stigma for students who are pulled out because they are designated EC or for remediation. “So every single kid is going somewhere to get pushed further,” said Heather Webb, an interventionist, “and we do that K-5.”

Educators hold each other accountable. One interventionist described how she feels as she takes a student back to a teacher if she doesn’t feel like she has made the progress intended. “You are going to have to look the teacher in the eye,” said Webb.

Here are some interesting examples and observations.

During the pandemic, educators focused on power standards instead of micro skills. They gave the example of a third-grader who was in kindergarten when the pandemic started. She is a champ, they said, when it comes to reading. She reads fast, fluently, and accurately. But she can’t do nonsense words. They are debating the appropriate intervention.

Some classrooms didn’t meet growth because of particular student outliers. That, they said, requires a whole different intervention.

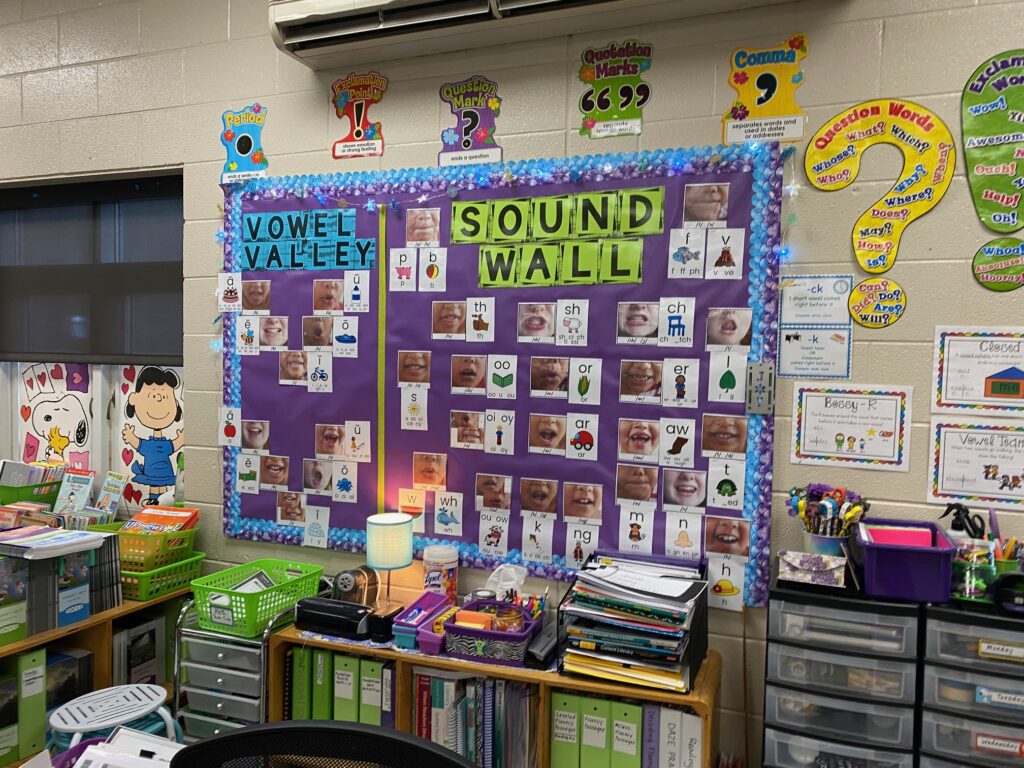

Tammy Massey, who has been profiled by WLOS, said, “I just look for our data, our students to be performing better and better and better after we had this LETRS training because THAT is amazing. I mean it’s just eye opening. I’m never going to teach the way I taught because that’s not how students learn.” There is buy-in here for this districtwide, state-mandated training.

This very intentional, student-by-student approach makes a difference.

You can see it in the student data posted around the school. And you can see it in the school motto posted as you walk into the school: “We work together to succeed using rigor, relevance, and meaningful relationships.”

Educators and leaders collaborate to provide solid core instruction and regularly dig into the data to determine how to extend and personalize learning for each student.

— Jeremy Gibbs, DPI’s Regional Director, Western North Carolina

Brush Creek Elementary

‘Growing together’

Brush Creek Elementary was one of just eight schools in North Carolina in 2021 to be designated a National Blue Ribbon School by the U.S. Department of Education for overall excellence and closing academic gaps.

Susan Jackson is the principal, and she is all about her BEARS — which stands for “Believe, Educate to Achieve, Ready to Succeed.”

The school’s story, Jackson said, “centers around growing together. That’s our biggest goal.”

“However that looks,” she said, “because it looks different for all 335 students and 85 staff members.”

This school is focused on the whole child. The county librarian was reading to kindergarteners. A behavioral therapist was working with a student. A speech therapist was testing hearing.

There is a school pantry for food and supplies.

“Seven students in a grade level can make or break growth in a small school,” said Jackson. That requires being proactive in addressing adverse childhood experiences with counselors, social workers, and school nurses.

At Brush Creek Elementary and in all of the schools in Madison County, these wraparound supports for students have been needed before, during, and after COVID-19 to sustain excellence.

“The students are why we are doing this,” said the superintendent. “It’s about getting deeply into teaching — not some manual-driven, OK here is the policy, what you are supposed to do as the teacher. Our teachers are digging deeper than that for our students.”

The growth mindset

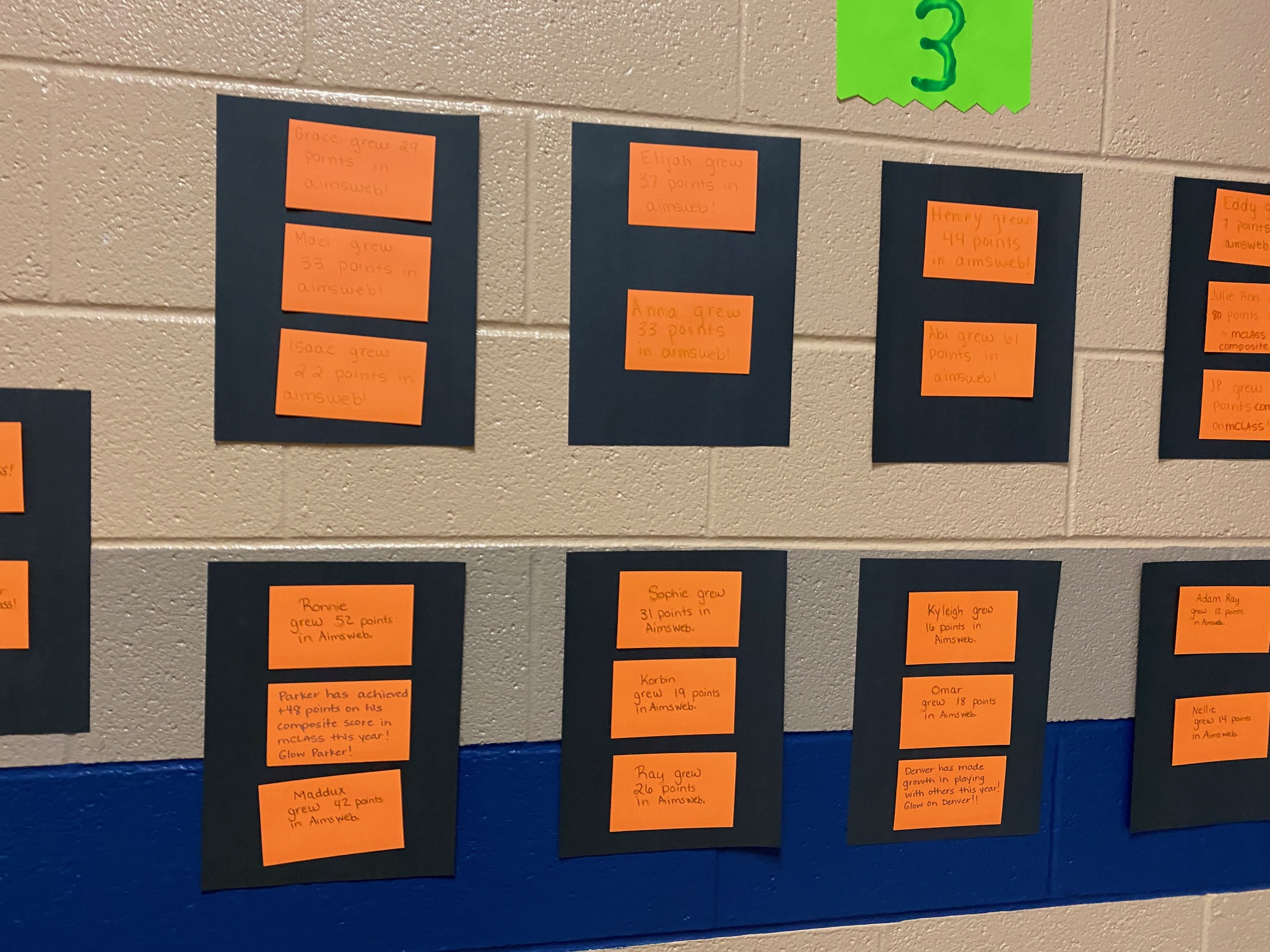

Around the principal’s office, there are posterboard-sized sticky notes reflecting what teachers are proud of by grade:

Kindergarten: scores rose tremendously, routines in place, small classes improve student learning, learning to be a student, ability to follow multi-step directions

First grade: smooth transitions, reading growth, math progress, mid year “bloom,” maturity, helping each other and peer support

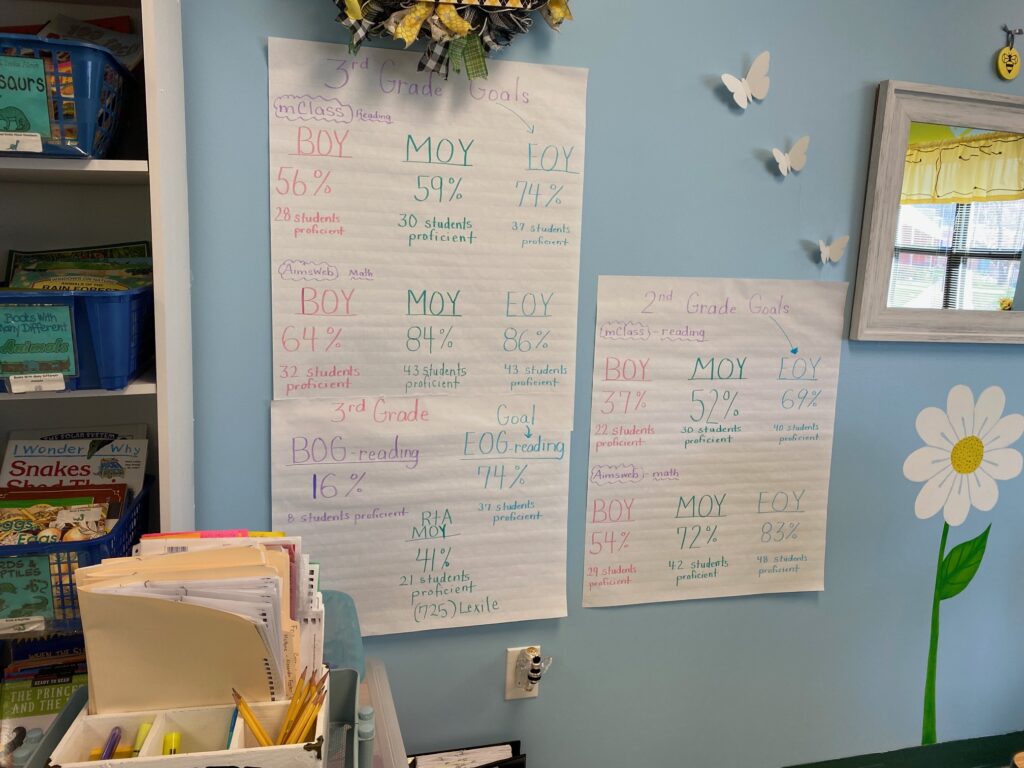

Third grade: mClass growth, strong Aimsweb math skills, 21 students have met RtA, huge growth on MAZE, support for students

Fourth grade: amazing reading growth for EC students (over 50+ word count per minute at 99% accuracy), reading growth for AIG students, improved multiplication fact fluency, overall ORF-ACC, kids have goods attitudes and are excited about growth

Fifth: all kids making progress in multiple areas

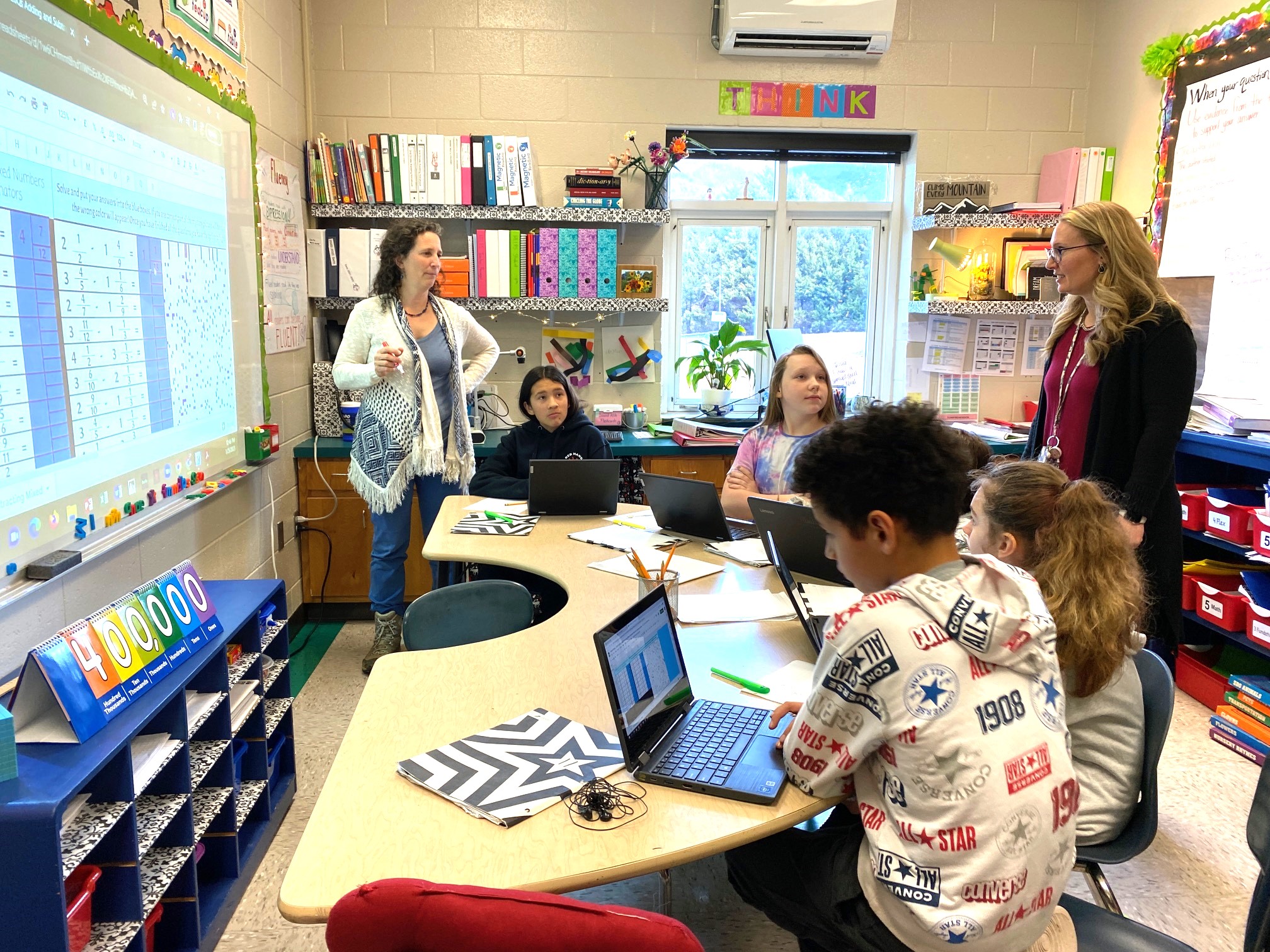

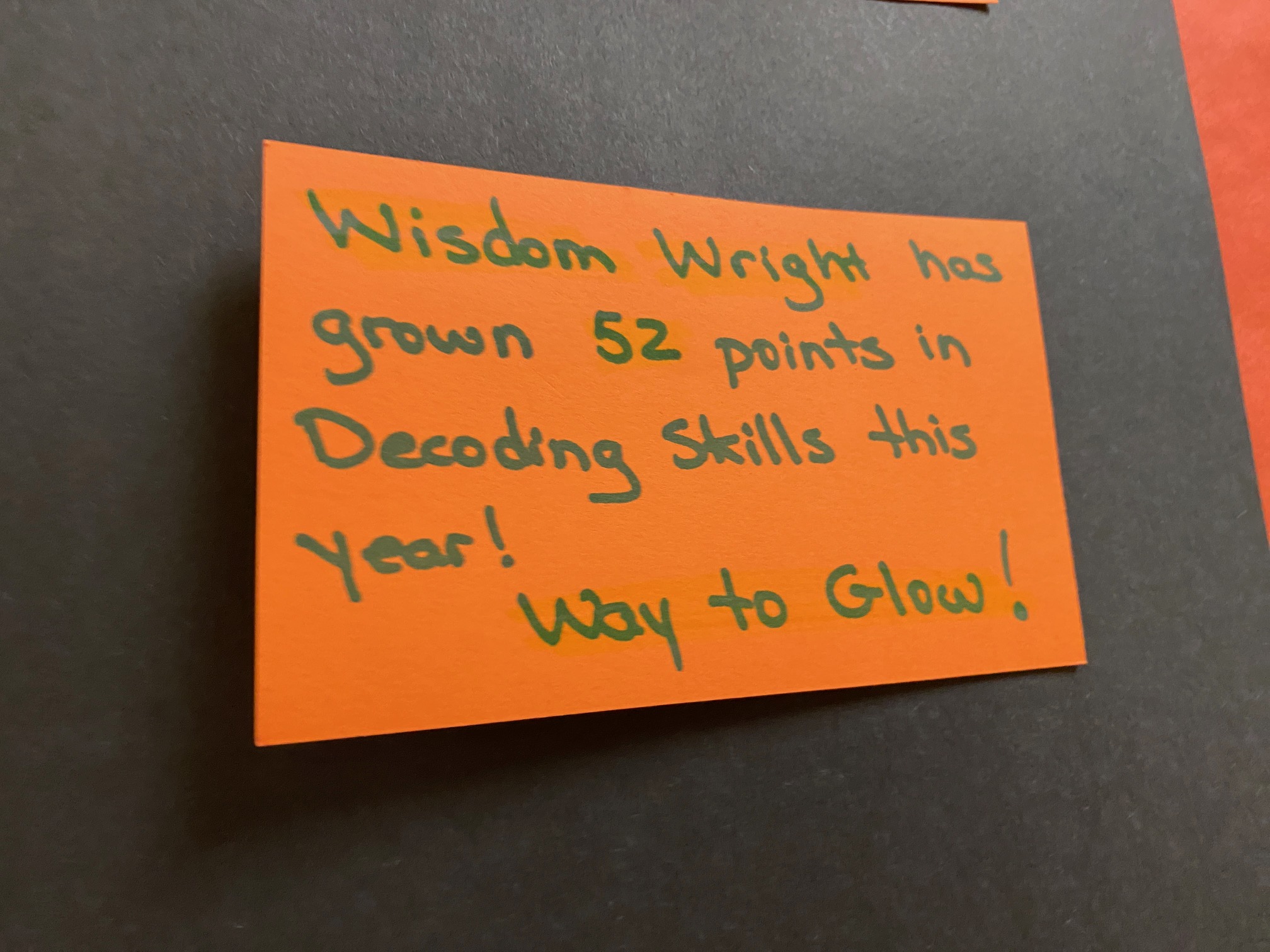

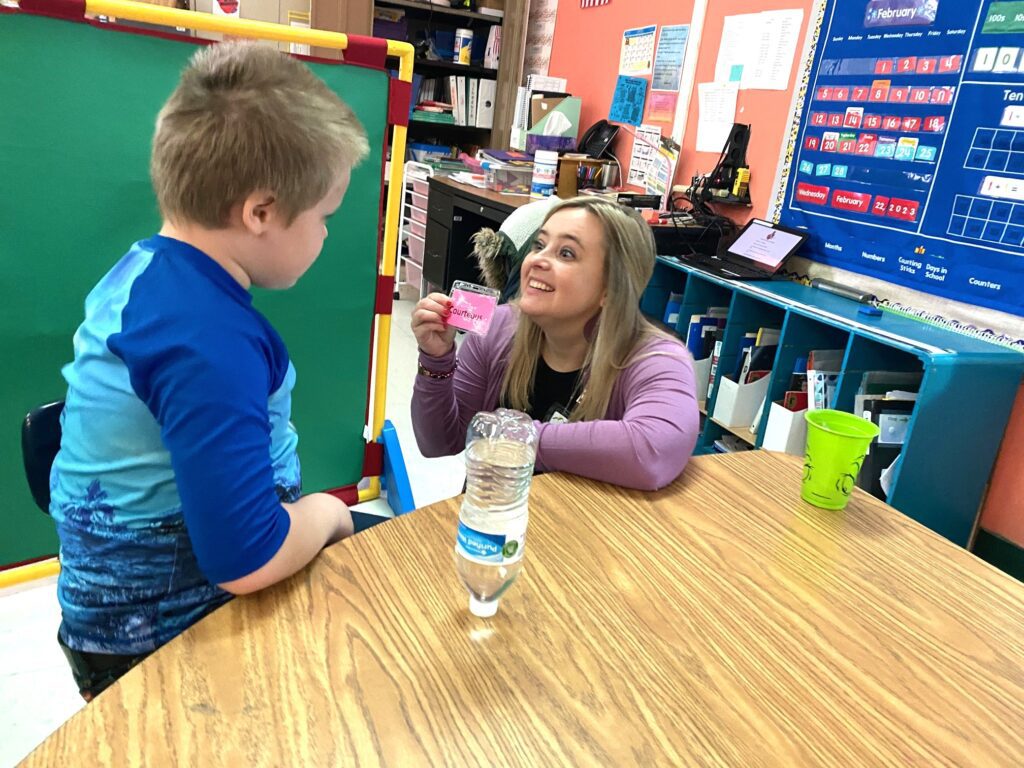

The principal and the superintendent tell me it is important to get kids connected to their own data. Thanks to federal funding, three interventionists serve this school.

These students are practicing medial sounds. In barbecue, “be” is the medial sound. Dropping the bar to isolate the “becue” is tough. Here you can see the students working on magnify.

Data showing the progress of third grade students is posted on the wall close by.

Jackson tells the story of a fourth-grader who was homeschooled during COVID-19. “He does have gaps. We even considered retention,” she said. But with targeted intervention, the student moved from 41% to 83% proficient.

Susan Ball teaches fourth grade. She has been teaching for 20 years. Ball talks to her students out loud about the need for a growth mindset. It is not about passing the grade, she said. It is about each and every day understanding what the student can do and what they can do well.

“My kids know their data. It’s celebrated,” she said.

Just four of her 15 students passed their first reading check in. Eleven of 17 passed the second one.

“Our kids don’t just celebrate their own growth,” Ball said. “They celebrate each other’s growth. We are a family.”

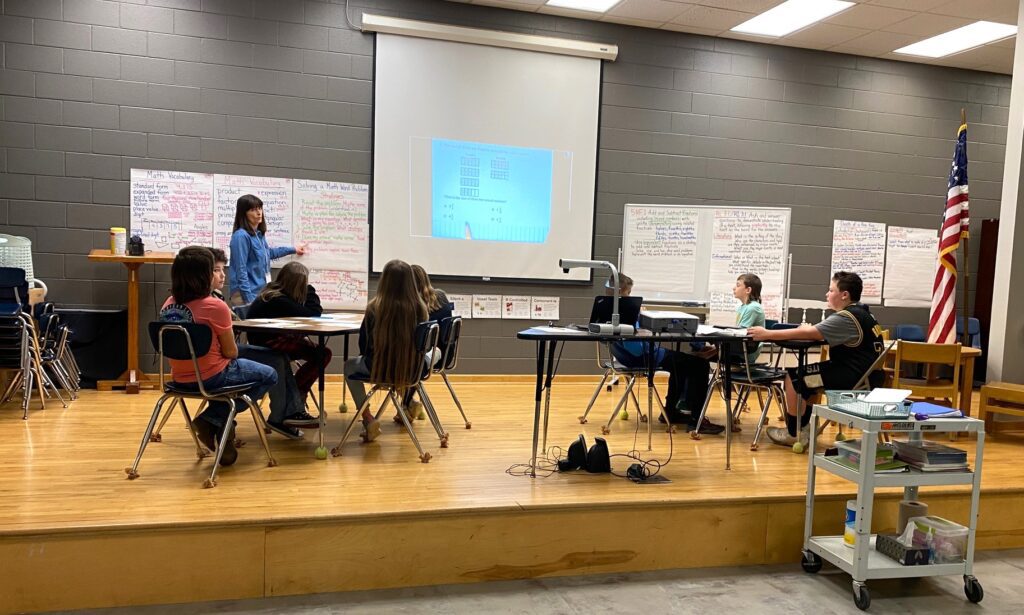

Every square inch of space is being used for intervention in this school, including the stage in the auditorium.

This is the first year this school is using NC Check Ins 2.0. Robin Bishop is trying to get these fifth grade math students accustomed to the technology-enhanced questions.

This will be the first year that third, fourth, and fifth grade students have taken the reading check in online.

“We are a little bit worried about the transition to online because we spent so much time teaching them how to have that text in their hand, and reading with a pencil in their hand, and marking the text,” said Bishop. “This year, we are trying to transition them to the tools they have online, like the highlighter tool. But they still have access to paper and pencil to take notes. Some kids can use that. Others can’t.”

School leaders have been in touch with some of the assessment vendors to learn how to help the students transition.

In this transition to more and more online assessments, Jackson worries about what she calls “happy clickers.” Students are so used to playing video games, she said, they often click without applying their knowledge.

“It’s a challenge,” agreed Bishop.

Both the principal and this interventionist are eager to see whether the transition impacts student scores since good data informs so much of what they do here at this school.

Points of pride

If you have traveled in western North Carolina, you will know there is a fierce mountain pride throughout the region, and that is true in Madison County too.

Meet Rachel Ray, a Spanish teacher at Madison County High School, who is the regional teacher of the year.

Ray says, “I believe in infusing joy in every class I teach. I believe that passion and positive energy are contagious. I believe in capitalizing on what students CAN do, not what they can’t.”

Another point of pride for this community is the 10-year project to rehabilitate the Mars Hill Anderson Rosenwald School, which will serve as a cultural center “to promote a fuller understanding of rural Black history in the Southern Appalachian Highlands and to enhance education at all levels.” The district’s social studies and history teachers met there recently for professional development.

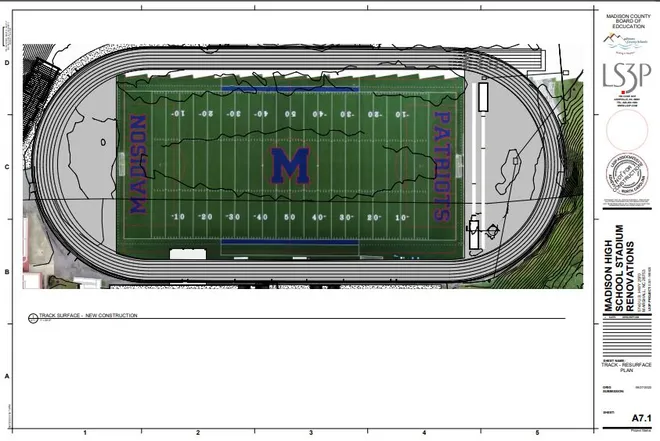

And then there is football. The high school stadium in Madison County was built in 1972. More than 50 years old, stadium renovations are underway with an emphasis on accessibility, including grandstands, locker rooms, restrooms, parking, a new track, and indoor batting cages and pitching fields. The renovations are being paid for through a local quarter cent sales tax passed in March 2020, an appropriation by the legislature, and DPI’s Needs-Based School Construction Grants.

Hoffman believes strongly in the “critical role our schools play in the life of our community.”

The district’s vision statement says, “students of the Madison County School system will have meaningful experiences and valuable academic preparation to ensure a brighter future.”

It’s a vision worth future investments.

Through high standards, clear expectations, thoughtful planning, systems thinking, and authentic leadership they consistently challenge each student to grow and achieve at high levels.

— Jeremy Gibbs, DPI’s Regional Director, Western North Carolina

Recommended reading