Research Triangle High School (RTHS) opened in 2012 with high hopes and an innovative teaching model. A public charter school founded by Pamela Blizzard and Eric Grunden — charter pioneers from the enormously successful Raleigh Charter High School — RTHS sought to leverage technology to “flip” classroom learning. Students would watch lectures online at home and then apply that learning in class. Unfortunately, early outcomes did not match early hopes.

“We opened as a fully flipped school, thinking that that technological shift would be really magically engaging for children and really change their experience of learning,” says Blizzard, who serves as RTHS’s managing director. “We learned really quickly that if kids don’t do school, if they don’t know how to learn, changing something like one of the tools that they used was not the answer at all. They just didn’t do that kind of school.”

Undeterred, RTHS added myriad interventions that “moved the needle a little bit but they didn’t move the needle a lot,” Blizzard says. The dilemma: How to help all of RTHS’s students, who arrive on campus with vast differences in ability and hail from 60 different middle schools? Blizzard, a Northern California native, “fell into” the answer on a visit back home. Fifteen minutes into a school presentation about personalized learning from Summit Schools, a charter management organization in California’s Bay Area, Blizzard had an epiphany: “This will do the thing that we’re trying to do, which is differentiate learning and pull the kids who are behind up to grade level and allow the kids who are really accelerated to continue to accelerate.”

Personalized learning, begun as a pilot at RTHS, now operates school-wide. The school’s model is a marriage of technology and instructional ingenuity. Data from Summit’s software platform inform the pace of learning for each student. Students then apply what they learn in real-world projects. Each week they meet with a mentor to hone habits of success.

“It has been transformational for our school,” says Blizzard.

A shifting K-12 technology landscape

From RTHS to classrooms around the globe, technology has altered the landscape of learning. More change is coming. Ben Davis, a senior market analyst at UK-based Futuresource Consulting, tracks education technology trends worldwide. What’s the forecast?

“Virtual reality is on the radar. It’s something we hear a lot about,” says Davis, with a key caveat: “The price points are still prohibitive in a lot of cases.” Coding and robotics are growing, “with lots of different platforms and curricula.” Davis adds, “Where we are seeing high growth is with developer kits,” from LEGO, or those featuring responsive robots Dash and Dot.

Data integration and analytics loom large, featuring the rise of companies offering data management solutions. The next couple of years, Davis predicts, will usher in even “more use of data and analytics to inform learning in the classroom,” along with greater sophistication in adaptive learning platforms. Get ready: learning is becoming increasingly personalized.

In technology adoption, the U.S. sits at the front of the global classroom. Other advanced markets include Australia and New Zealand, with numerous “bring your own device” (BYOD) programs, as well as the Netherlands and the Nordic region. “Sweden especially is quite advanced and has lots of state-led and municipality-led programs [focusing on] online assessment and digital curriculum,” says Davis.

In North Carolina, “many antecedents to success”

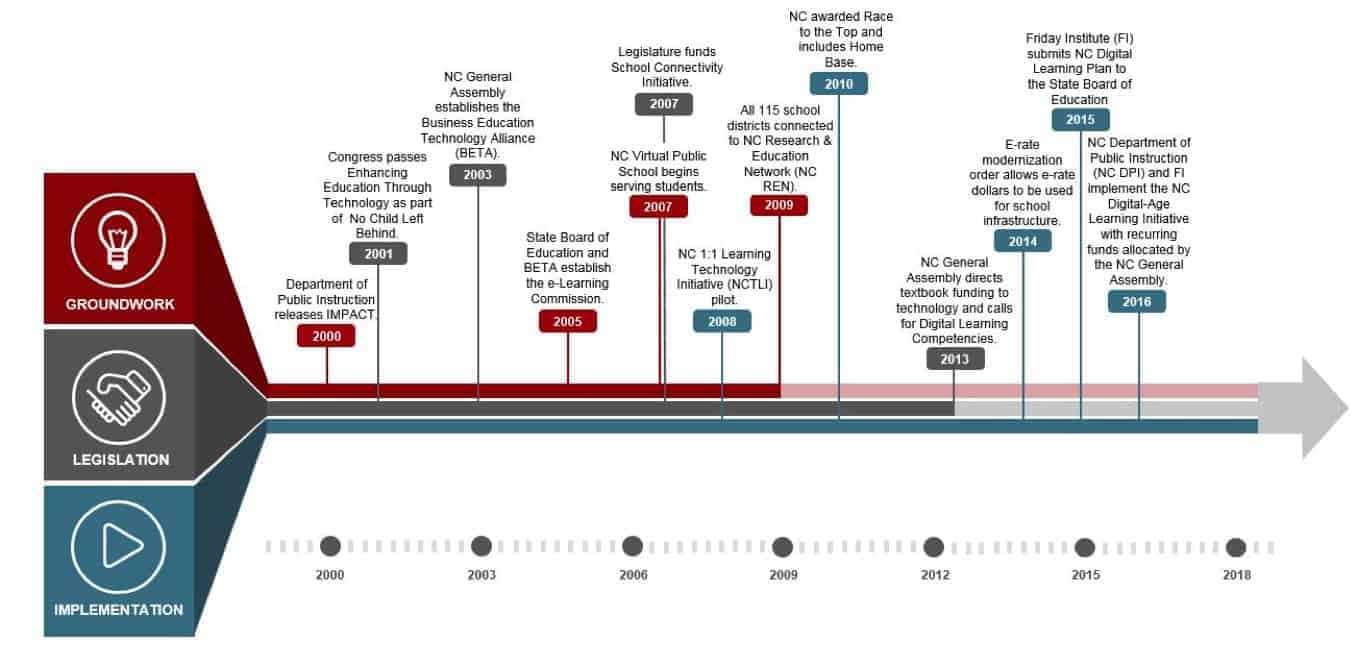

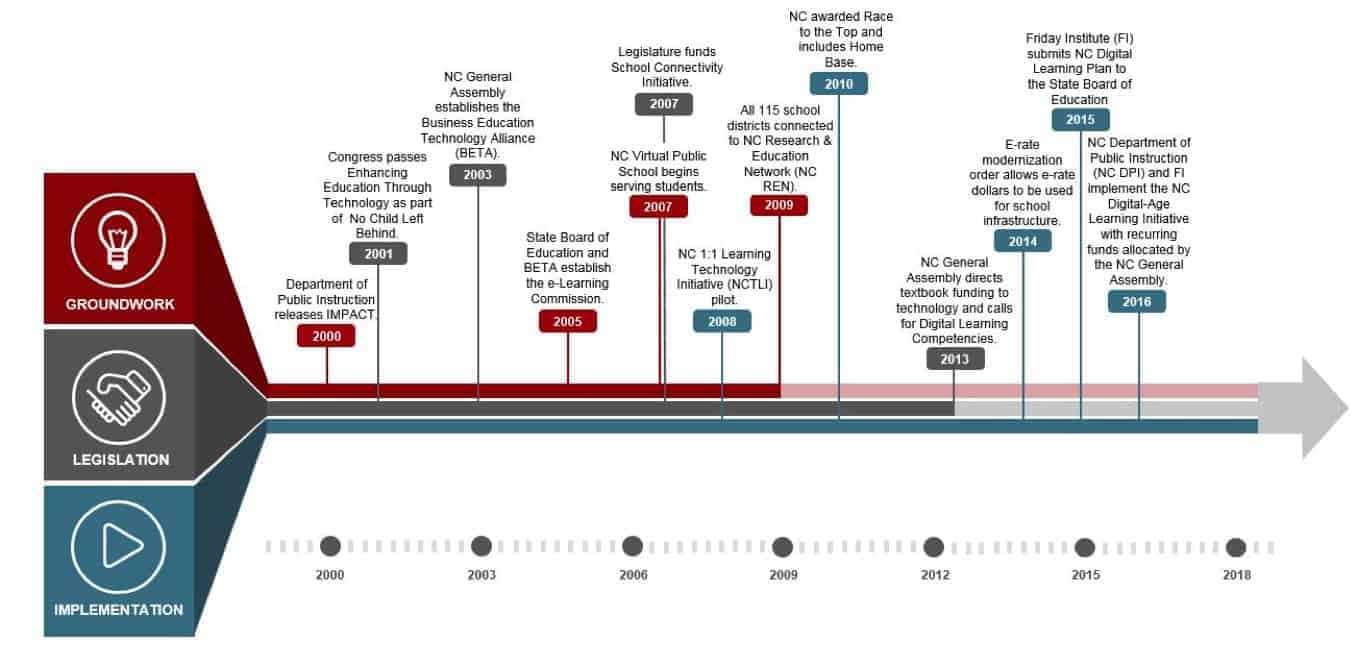

In North Carolina, work to integrate technology into K-12 classrooms began years ago, with “many antecedents to success,” says Dr. Maria Pitre-Martin, Deputy Superintendent for District Support at the North Carolina Department of Public Instruction (DPI). “A part of our journey is realizing that these things don’t happen overnight. You have to have steps,” says Pitre-Martin.

Early steps included the release in 2000 of IMPACT, DPI’s guidelines for media and technology programs. Since 2003, some schools around the state have implemented the IMPACT model. Other steps included establishment in 2005 of the state’s e-Learning Commission and approval in 2006 by the State Board of Education of goals aligned with preparing “Future-Ready Students for the 21st Century,” including technology access and skills. In 2007, the General Assembly funded the School Connectivity Initiative (SCI), focusing intensive efforts on network access and technology infrastructure for schools. That same year the North Carolina Virtual Public School opened; NCVPS now offers more than 150 online courses to students statewide.

More initiatives followed rapidly: 2008 marked the launch of a three-year evaluation of the North Carolina 1:1 Learning Technology Initiative, a pilot program providing a laptop to every student and teacher. The next year yielded another milestone: connection, as part of the SCI, of all 115 school districts to the North Carolina Research Education Network. Home Base, the state’s instructional improvement system, followed in 2013 with widespread adoption by school districts. “During the first year, DPI provided funds through Race to the Top to allow districts time to experience Home Base. Since then, 100 percent of our districts have chosen to use our instructional improvement system,” says Rosalyn Galloway, Home Base Manager at DPI.

Other milestones included greater funding for Wi-Fi access through the 2014 federal E-rate monetization order. In 2015, North Carolina’s Digital Learning Plan, prepared by the Friday Institute for Educational Innovation at NC State University, set strategic goals. Digital learning grants, authorized by the General Assembly in 2016, provided support to districts in the planning stages of digital learning programs and enabled advanced districts to “showcase” successes.

Highlights of North Carolina’s Path to Digital Learning

Classroom devices and content

Schools are steadily increasing student access to digital devices. According to Nathan Craver, data, assessment, and continuous improvement consultant at DPI, draft 2017-18 numbers show 50 percent of North Carolina schools issued devices to students in at least one grade. Around 20 percent of schools sent devices home with students, and 29 percent of schools leveraged “bring your own device” programs, allowing students to use a personal device for classroom learning.

An ongoing challenge for educators, given the sheer volume of digital content, is tapping into resources while ensuring content quality remains high. In 2015, the U.S. Department of Education launched the #GoOpen campaign to promote the use of openly licensed educational materials. North Carolina signed on and has since been working on procurement for an open education resources service. Professional development will train teachers to use those resources effectively.

“That work is really taking off,” says Donna Murray, digital content, coaching and communications consultant at DPI. “Once we get the contract finalized,” says Murray, professional learning will enable educators to “really delve into how to find, vet, and use digital content, especially around the idea of open educational resources.” Teachers will have “what they need, when they need it,” says Murray.

Scaling successful approaches

How do all of those steps come together for North Carolina schools moving forward? The focus is on personalized learning. The center of RTHS’s approach and the top priority for school leaders nationally — according to the 2017-18 Digital School Districts’ Survey — personalized learning also figures prominently in the state’s digital learning strategy and plan to comply with the federal Every Student Succeeds Act, or ESSA. North Carolina’s ESSA plan identifies four pillars of personalized learning:

- A student “learner profile”

- A learning path that is individualized to the student

- A “competency-based progression” emphasizing mastery, not seat time

- A flexible learning environment.

Home Base is part of these efforts, says Galloway: “The latest system updates allow districts to drill down into the data to better understand where students are being successful and where they need extra support. The department works to make sure districts have Wi-Fi to be able to use the tools effectively in instruction. Home Base suite has helped lead us toward personalized learning.”

How can the state fulfill the promise of personalized learning? Schools and districts are showing the way.

“Digital learning grants have a personalized learning strand. [This] allows us to really dig into those districts that are using personalized learning. Those practices can be scaled up,” says Pitre-Martin, who intends to build a team of internal experts. “One of the next steps is to develop a cadre of personalized learning champions within our building,” she says. “Success-makers” at the school and district level can help devise best practices. A toolkit, devised by champions, can then “show others what this looks like,” says Pitre-Martin.

The recipient of a digital learning showcase grant, RTHS is doing its part, hosting 150 educators for a training session last spring to model the personalized learning approach. Word has spread far beyond the state’s boundaries. This year, English teacher Jason North moved cross-country from Seattle for the chance to teach at RTHS.

For North, personalized learning just makes sense. “One size usually doesn’t fit all when it comes to students,” he says. “It’s not just teaching them this content or this academic thing. It’s also teaching them how to learn.”