At 5:00 on Tuesday, May 7, the crowd began to gather outside Elkin Elementary School in Elkin — a small town in the foothills of North Carolina. Food trucks arrived in preparation for serving dinner to the expected masses while inside 17 teachers accompanied by students from their classrooms completed the final touches on their student showcases. At 5:30, the doors opened and a rush of children, many dragging parents by the hand, poured into the gymnasium for the school system’s very first project-based learning (PBL) expo. At the expo, student work was on display for both their families and business partners in the community who had been invited to see the work students were doing and, in some cases, to be a part of that work.

A few weeks later and almost 200 miles away in North Carolina’s coastal plain, 72 teachers from Johnston County Schools with help from their students were similarly engaged in the 2nd annual Innovation Expo at the Johnston County Medical Mall. Both counties, in partnership with RTI International, are shifting their instructional culture to emphasize PBL and to highlight the work of their teachers and students in public-facing end-of-year expos.

PBL is an approach to learning that begins with a problem to solve or project to complete that requires acquisition of content knowledge across time. Through a sustained, inquiry-based approach, students develop the skills to solve the problem or complete the project while also learning the required curriculum. PBL begins with a driving question to spark student curiosity and propel learning and ends with a public presentation of work.

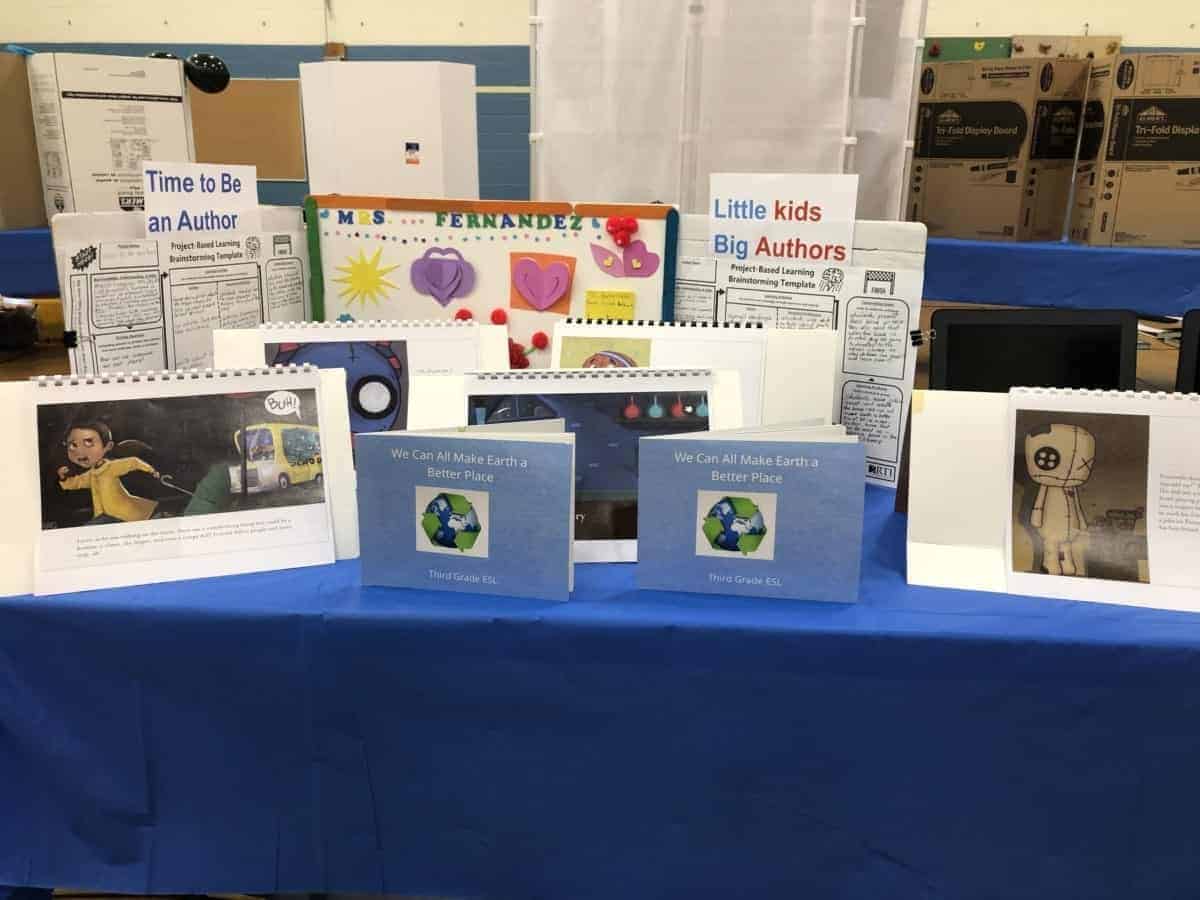

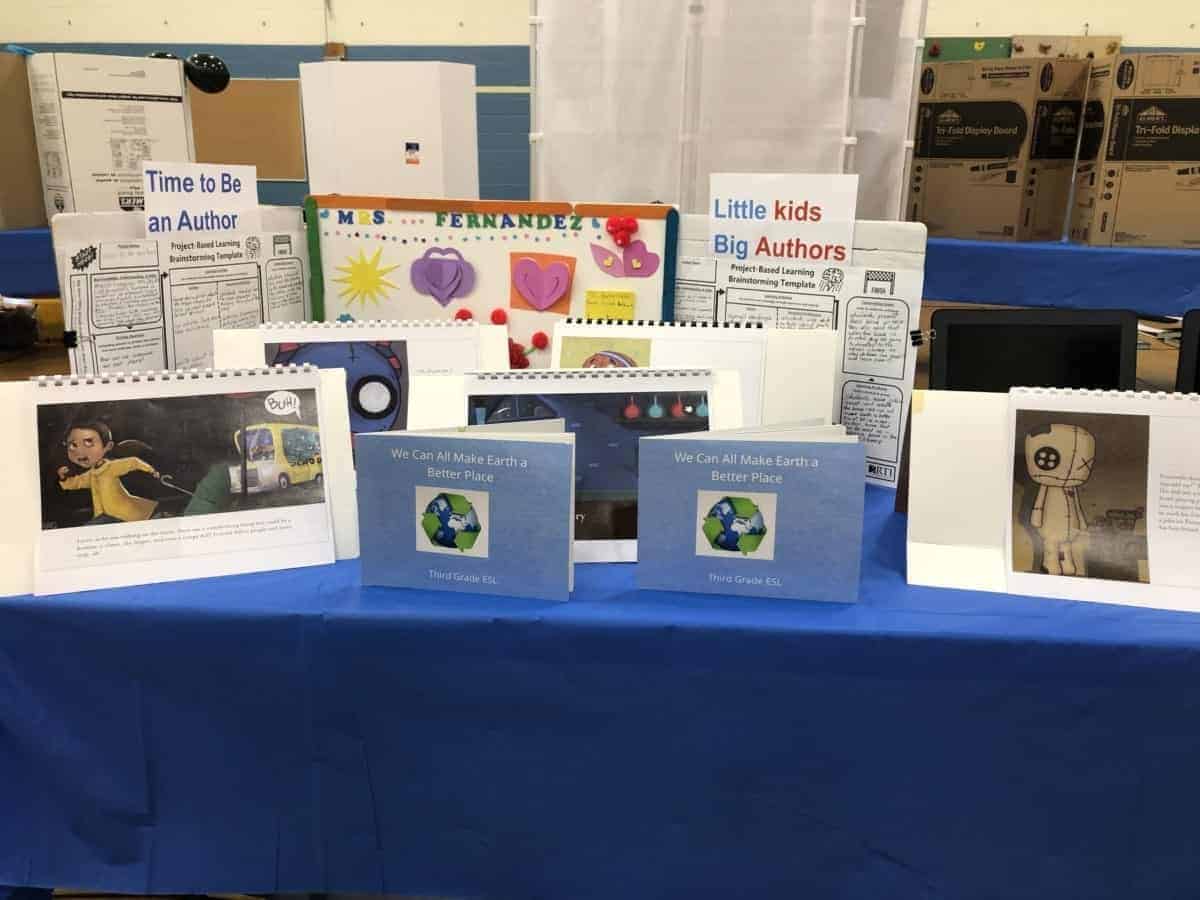

For example, English as a Second Language (ESL) students in Elkin began with the question: How can we be better citizens of our planet and take care of our Earth? After an exploration of science standards related to sustainability, students wrote children’s books answering the driving question that were displayed at the expo. To increase the publicity of their work — and to emphasize speaking skills — each book included a QR code, allowing readers to access an online audio recording of each child reading their book out loud.

The emphasis on a public audience in PBL has many benefits. To start, a public audience increases student motivation. As John R. Mergendoller writes, “nobody wants to look ill-prepared or display a second-rate product before a public audience. Making student work public ups the ante for both students and teachers.”

But the power of the public audience goes far beyond simply motivating students to do their best work. The true power of the public audience lies in a deeper impact on students when they share work outside of their classrooms. Mergendoller also says, “The feedback and questions [students] receive from an audience prods them to reflect on and analyze their own thinking. . . When products are taken seriously, and considered worthy of critique and discussion, this encourages students to perceive their work as valuable, and themselves as creators who can take pride in their products and accomplishments.”

When students have a public audience, they feel a sense of contribution. Additionally, the exchange of ideas between students and adults enhances and expands student learning beyond the classroom, providing students with multiple perspectives and access to feedback beyond their classroom teacher.

If you haven’t had the chance to experience a PBL expo, here are some examples that show how students in Johnston County — from elementary school to high school — shared their work with their public audiences, expanded their thinking, and boosted their confidence and self-efficacy.

Wilson’s Mills Elementary School

Fourth graders engaged in a 2-part project designed to answer the following questions: “Should all people be treated the same?” and “How can we design a place where everyone can play?”

During their unit, which covered literacy skills, graphing, area and perimeter, and economics, among other topics, students read novels about characters with disabilities, observed special needs classrooms, and visited an inclusive playground in Smithfield. They created a budget, planned and built models of possible inclusive playground designs, and organized fundraisers to pay for their ideas.

But their work didn’t stop there. Because PBL includes a public audience, students presented their plans to their PTA, asking the PTA to match the $347 already raised by the students through their own fundraising efforts. Students also shared their work with local businesses, including Partnerships for Children, an organization that builds inclusive parks and helped students with their playground designs, and Acera Wealth Management, an organization that donated an additional $500, bringing total funds for the park to almost $1,200.

Student Katee Culbreth said: “I’m really starting to like presenting to other people because I know it will make a difference in what they think and what I think.”

Her classmate, Conner Sams, added: “I learned that people can make a difference. We are showing the world that people need to work more to help people with disabilities.”

Archer Lodge Middle School

Sixth grade social studies students learning about government and economy through a study of Ancient Greece and Rome, where the idea of advocacy originated, were asked to find a solution to a modern problem that would help change the world and to become advocates for their solution. Topics students chose included providing assisted care residents more opportunities for recreation, increasing melanoma research, and saving endangered animals.

Students Kadelyn Alford and Abby McNally chose to find solutions for school safety and presented their work to Ross Renfrow, superintendent of Johnston County Schools, Rep. Donna White, and Rep. Larry Strickland, who is also a former school board chair.

Of her experience, student Kadelyn Alford said: “[Having a public audience] made me more confident. When people come see your project, it helps get the word out so people can help us with it.”

West Johnston High School

Ninth graders in World History created websites to accompany historical fiction and provide social, cultural, economic, and political background on the time period of their selected novel. Their project and their websites were intended to help them and others “climb into the skin” of people throughout history — with a special emphasis on those who lived through genocide.

Through researching the time period and creating a website that English and history teachers could use with their own classes, students not only gained new perspectives but also provided perspective for others.

Student Aidan Schweizer said: “It was just an amazing opportunity getting to step out of our boxes and present in front of an entirely new audience who was actually interested and invested in what we had to show.”

The student work in Johnston County and Elkin City show what can happen when students feel that people outside of their classrooms are invested in their work and believe in their capacity to make a difference. When this happens, students can change the world — and this is the power of the public audience.