In 1994, Halifax County Schools was one of the original districts in the Leandro lawsuit that resulted in the state Supreme Court saying that the state was not living up to its constitutional obligation to provide the “opportunity to receive a sound basic education” to all children. In 2009, the judge in the still-ongoing case said that an “academic genocide” was taking place in Halifax. That year, the state also began intervening in the district.

In 2015, EducationNC visited Halifax County Schools and chronicled some of what was happening with the district’s board of education.

That year, the state also took over the budget in the district. Things were looking up. The district moved out of last place for academic performance. And then in 2016, the district got a new superintendent, Eric Cunningham, and things began to change even more.

A little background

Halifax is a unique district. It is one of three school districts within Halifax County, two of which, Halifax County Schools and Weldon City Schools, are majority Black, and one of which, Roanoke Rapids Graded School District, is majority white.

At one point, a lawsuit sought to merge the three districts, arguing that an inequitable distribution of resources has negative impacts on some of the districts in the county. For instance, Roanoke Rapids Graded School District had zero low-performing schools, while 75% of Weldon City Schools was low-performing and 50% of Halifax County Schools was low-performing in 2018-19.

In October 2020, members of the state Department of Public Instruction traveled to Halifax County Schools to meet with district staff there, including Cunningham. Cunningham explained what it’s like in his district and what he and his staff are trying to do.

He said that his district is striving to provide every child with a sound basic education “within the limits that we have.”

He said he knows the district isn’t where it should be. But it’s getting better. And now that the two sides in the Leandro lawsuit have come up with a plan to help ensure a sound basic education for all children in the state, he said a “brilliant course” has been set that will help districts like Halifax.

But it hasn’t been easy. And he is honest about what the district has faced.

The Halifax community

The community served by Halifax County Schools is poor. According to the North Carolina school finances website, the annual median household income in Halifax County for 2017 was $33,573. The annual median wage was $24,629.

Cunningham talked about his first year on the job in Halifax and how he rode the bus to school with the kids.

“I saw some things that just shook me to the core,” he said.

He described two things he saw one day in particular. One was a woman getting water from a well. She didn’t have running water in her house, he discovered. At another house, he saw a woman lift her front door off the hinges and move it out of the way so that the child could leave and get to the bus.

“That bus ride changed me that day,” he said. “My whole attitude shifted. No longer was this a job, a means to an end, a job for another job. It became a mission then, because that experience made me take the blinders off.”

Charting a new course

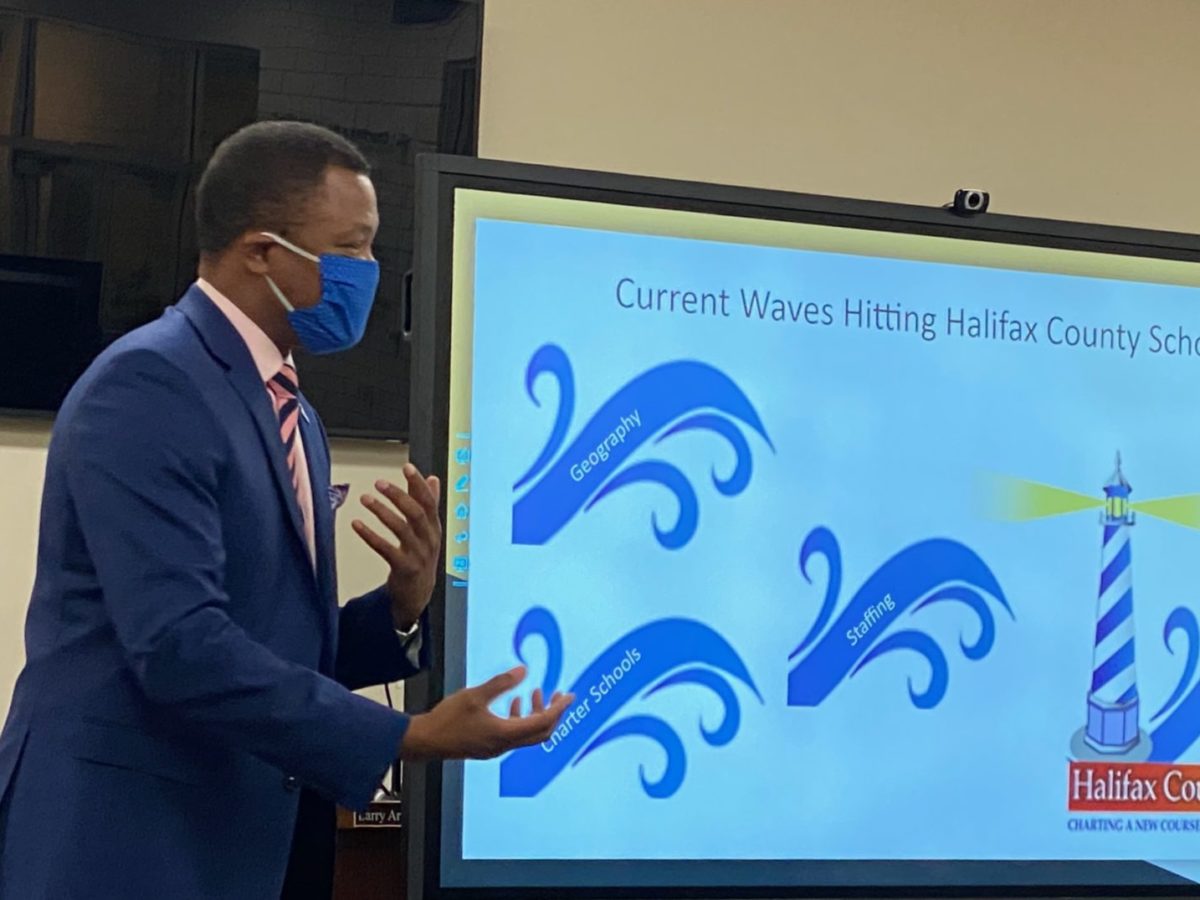

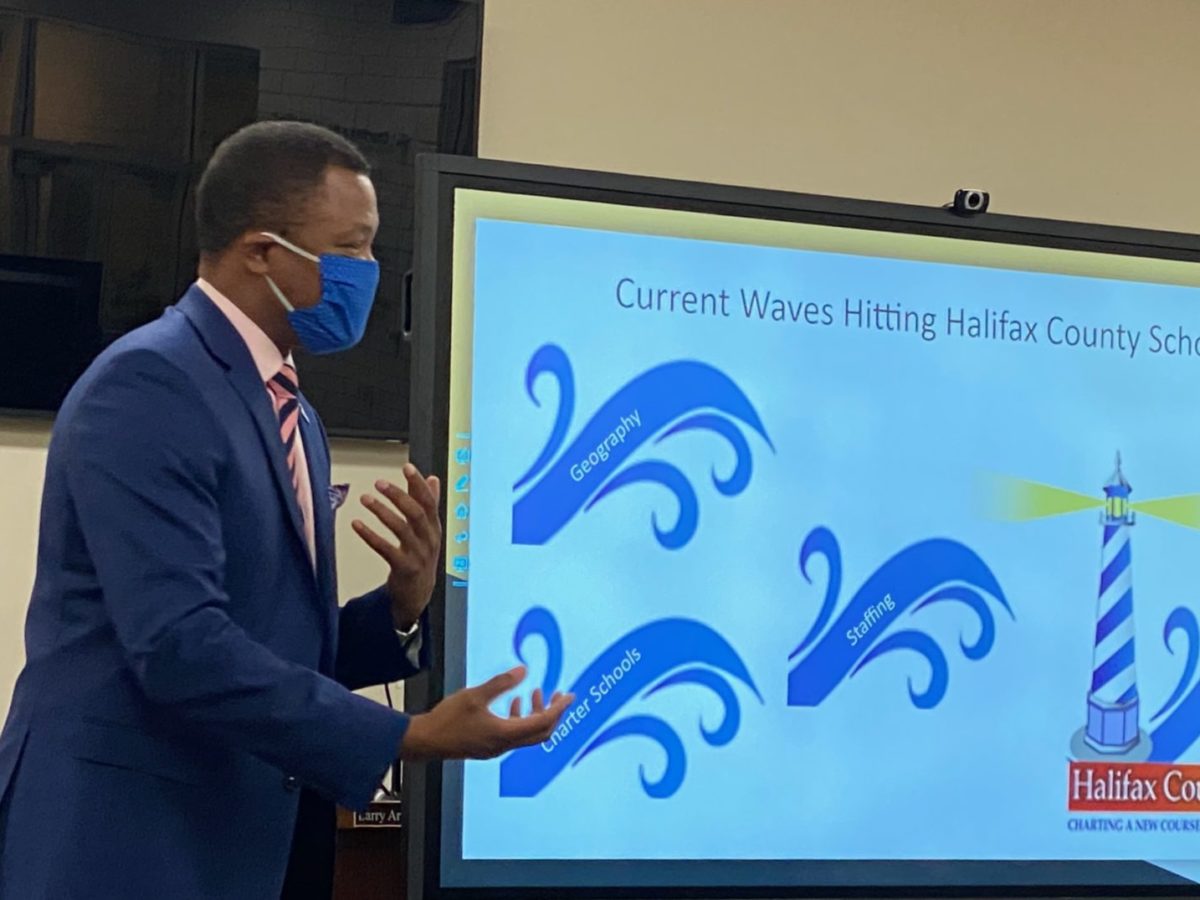

Cunningham and other staff began a rebranding of the district, putting out a document called “Charting a New Course,” in which he wrote that the district was “re-imaging the school district’s vision, mission and goals.” But to do that, the district had to know where the district was, where it was going, and how it was going to get there.

When he first got there, Cunningham studied. He said he looked at the schools and examined some of the core components that educators know make up an effective school, including:

- Instructional leadership

- Clear and focused mission

- Safe and orderly environment

- Climate of high expectations

- Frequent monitoring of student progress

- Positive home/school relations

- Opportunities to learn

- Student time on-task

“For the entire first year, I’m looking for these … and how deeply they are embedded in Halifax County,” he said.

That showed him where he had to focus. And he started with safe schools. As part of that, the district hired two school resource officers for one school and developed better relationships with local law enforcement.

Staff also had to think about how to address issues with student achievement.

“We have students several years behind with major skill deficits. Major. Three and four years behind. Day one. That’s why we had to spend $400,000 of our pre-K money to double our allotment and give kids an opportunity to come to school early,” he said.

Kids entering kindergarten were coming in with major deficits, so starting earlier seemed necessary to give them a jump start.

“If it were up to me, our babies would be in school at age 3,” Cunningham said.

Cunningham also gave a plug for the importance of instructional minutes: measuring the actual number of minutes that kids are receiving instruction.

“If we don’t put minutes into our children, they’re not going to grow,” he said. “It’s all about minutes. Quality and quantity.”

District staff looked at ways to reduce the time that teachers have to spend on things other than instruction, like travel between schools.

But Cunningham said addressing the needs of the whole child was just as important.

For instance, one of the things the schools began to do is institute the use of uniforms. Cunningham said they looked great the first day. But by the third day of school, the uniforms were starting to look bedraggled. That was a problem that is usually outside the purview of a school system. But Halifax was trying to address the whole child, so the district had commercial washers and driers put in at every school.

“That’s not a problem with teaching and learning, that’s a factor that impacts teaching and learning,” he said.

The district changed its emblem to a lighthouse, something Cunningham said symbolizes schools. He called the schools “a passport to a better life.”

“If you follow our prescription, you will have a better life,” he said. “We are committed to improving our school system to where you will have a better life.”

These are just some of the things the district had been doing to improve. And their efforts do seem to have started paying off.

In 2017, the district moved off the list of low-performing districts — districts where more than half of the schools are low-performing.

Additionally, for many years, Halifax was last in the state for performance, but it moved up to 113 out of 115 districts in 2015, and it moved up one more spot to 112 in 2017. In 2018-19, the last year for which data is available, Halifax was still off the list of low-performing districts and had a lower percentage of low-performing schools than nine other districts. It was on the borderline, however, with exactly half of its schools low-performing.

In 2018-19, the district had a graduation rate of 77.8%, higher than the previous 13 school years.

Cunningham said that the district is trying to measure itself against itself, rather than against other districts.

“We cannot be compared to other richer, more prosperous areas,” he said. “But we can show that what we’re doing with what we have is working incrementally.”

And, he said, he has the support of the local board of education. They give him the freedom he needs to be creative, he said.

But Halifax cannot improve alone, Cunningham said. He told DPI staffers that Halifax needs help to overcome their challenges if they are going to continue to “chart a new course.”

And, Halifax also needs more resources. NC Policy Watch published an article about the Leandro court case and Halifax. In it, the writer mentions the report from an independent consultant that recommended additional resources for the state’s schools.

Cunningham was clear in that article about how important he thought those resources are.

“We need those resources desperately,” Cunningham is quoted as saying by Policy Watch. “We will operate effectively within our means with the resources that we’re blessed with. I’m hopeful that a solution can be found and that we can start to bring those resources to Halifax County Schools.”

Editor’s Note: This article has been adjusted to reflect the fact that the state began intervening in Halifax Schools in 2009