|

|

Angst about the death of the humanities comes in waves. It features debates about digital vs. low-tech methodologies, deconstructive vs. celebratory interpretations, and ivory-tower vs. popular interests. Recent discussions focus on how humanities departments are facing declines in enrollments and worries about the capacity of students to read actual books in a digital age. For universities, it’s not only a matter of enrollment and tuition revenue, but also about the point of humanistic methods.

While it is crucial to heed these warnings, and not take for granted the value of investing in the humanistic traditions we inherited, we see reasons for hope on the UNC-Chapel Hill campus. And we would suggest that the public — the community outside of university campuses — is an important but often overlooked part of understanding the value of humanities inside campus classrooms.

Medea at Carolina

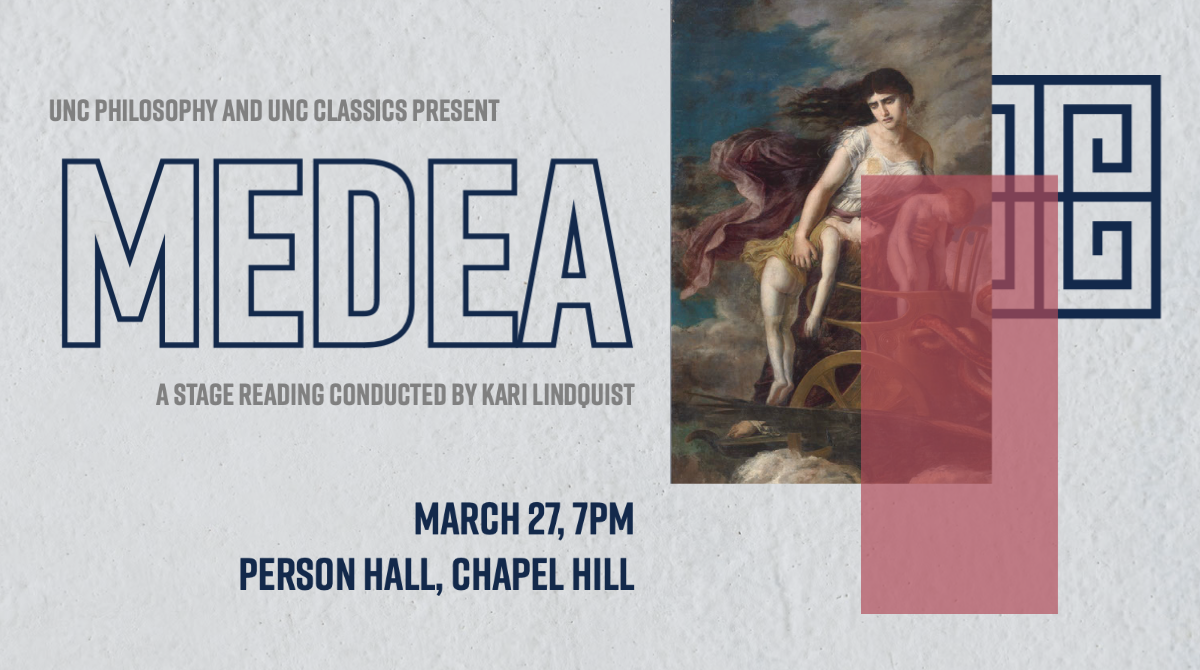

Here’s an example of how universities can embrace “grassroots humanities.” This spring, the name “Medea” took on a new significance at Carolina. Medea is a tragic figure who has stoked public imagination for over 2,000 years. Her story — especially the moralizing version told by the Stoic philosopher Seneca — invites us to reckon with the fragility of human goodness, grapple with the role of women in the ancient world, and consider the place of anger, love, and revenge in a happy life.

Medea’s story has been the basis for an unprecedented degree of interdisciplinary humanities collaboration and multigenerational community engagement in Chapel Hill. That collaboration now spans the philosophy, classics, and music departments, and includes events on and off campus such as reading groups, public talks, film viewing, and a staged reading.

This series of events began with a spontaneous question: what business does a Stoic philosopher have writing a pathos-inducing tragedy? Informal conversations among colleagues and students led to formal collaborations. Formal collaborations between departments and campus units snowballed into an interconnected series of public humanities events. Driving this process was a shared attraction to one story, to its paradoxes and (de)humanizing themes.

It helps to have well-trained professional humanists who are eager to collaborate. But the real catalyst at work was a classical text, one with the staying power to animate and sustain communities of inquiry.

We learned a few lessons from this experience:

First, public humanities programming is deeply enriched when it brings together folks across the lifespan. Medea’s story, like so much good literature and philosophy, is an invitation to multigenerational and face-to-face human connection.

Second, linking up multi-site and iterative programming on and off campus is an effective way to bring a wide range of folks into the fold. While our Medea programming includes a variety of engagement options, it all centers on the same story. The program rewards (but does not demand) continuous engagement across multiple events. Importantly, it has broken down campus borders by calling undergraduate students out into the broader community and drawing citizens into spaces on campus.

Finally, books! Physical books (especially free ones) are a catalyst. People treasured receiving their very own copies of the text to bring to events.

Sustaining public engagement with humanities

What does it take to create and sustain this kind of public engagement with humanities departments on campus? Institutional investment in public engagement is a big factor in creating the right conditions.

The Philosophy Department has a full-time Director of Outreach who teaches community-facing courses and creates programs that reach K-12 schools, community colleges, libraries, correctional facilities, museums, professional workplaces, and retirement communities. UNC’s College of Arts and Sciences offers public-facing humanities programs that focus on connecting academics to the surrounding community.

There is a social and civic function for spaces in which people can meet others and talk about ideas, free from political animosity or religious sectarianism. There is a growing network of off-campus civic institutions which are host sites for humanistic engagement, from the local independent bookstore to the shared learning associations among older adults. Creating space for community-engaged encounters with texts in public places is a great goal for modern humanists.

The work of successful humanities departments includes public engagement alongside the traditional goals of producing research and teaching undergraduates, creating a feedback loop. Undergraduate students benefit from the opportunity to create and facilitate programs with people well beyond their narrow age group. For the academics involved, opportunities to engage with core texts in a fresh way are generative for new ideas and insights. These experiences remind us why the humanities are worth researching in the first place.

And for everyone involved, there is a feeling of wonder and awe that comes with talking about old words and big ideas. It is rewarding to work out the plot points and hash out moral arguments about what various characters should have done. Often these texts provide a way into harder topics that might otherwise seem intimidating. Medea’s story opens doors for conversations about marriage and family, womanhood and parenting, exile and asylum, power and justice, crime and violence, and more.

There is hunger for public humanities, and there are plenty of reasons to read old books together. Here at UNC we plan to keep doing so. If you’re in the area, consider joining us on March 27 at 7 pm in Person Hall for a staged reading of Seneca’s Medea—the next installment in our ongoing project of democratizing the humanities.

As one of our community members recently put it, “So, what are we reading next?”